The economic cost of the COVID-19 crisis may pale in comparison to the human cost.

But both will be substantial. Measures to contain the virus have upended supply chains and financial markets and weighed on commodity prices, creating a perfect storm for the Canadian economy. Given the hit to both the services and goods-producing sectors, we expect real GDP to contract at a greater than 30% annualized pace in the current quarter.

Underpinning our forecast is the assumption that the economy will be severely disrupted for about 12 weeks, with activity gradually returning to normal after that. Confidence bands around this assumption are extraordinarily wide. Claims for employment insurance have reportedly skyrocketed, consistent with the unemployment rate reaching close to 20%. If these conditions persist for longer than we assume, the impact on the economy will be amplified.

Policies to address the crisis have been broad-based. The Bank of Canada lowered interest rates and announced other measures to ensure borrowers have access to capital. Canada’s government unveiled aggressive packages aimed at preventing large-scale business bankruptcies while keeping workers on payrolls. The ultimate success of these measures depend on the breadth and duration of the crisis.

Easing social distancing measures will alleviate some of the stress in the economy although persistently low oil prices will continue to weigh on growth. Oil prices are down $35 since the start of the year and are projected to average US$31 in 2020, just over half of 2019’s average price. This lower price environment will cut investment and result in permanent job losses. The impact will be felt disproportionately in the oil-producing provinces but will have spill-over effects across the country.

The drop in oil prices has already had a marked impact on Canada’s dollar which lost 10% against the US dollar before recovering some ground to stand at about 7% below its year-end level. Canada’s currency is likely to remain around 70 US cents in the near term as uncertainty about the depth and duration of the crisis sees investors gravitate to the safety of US dollars.

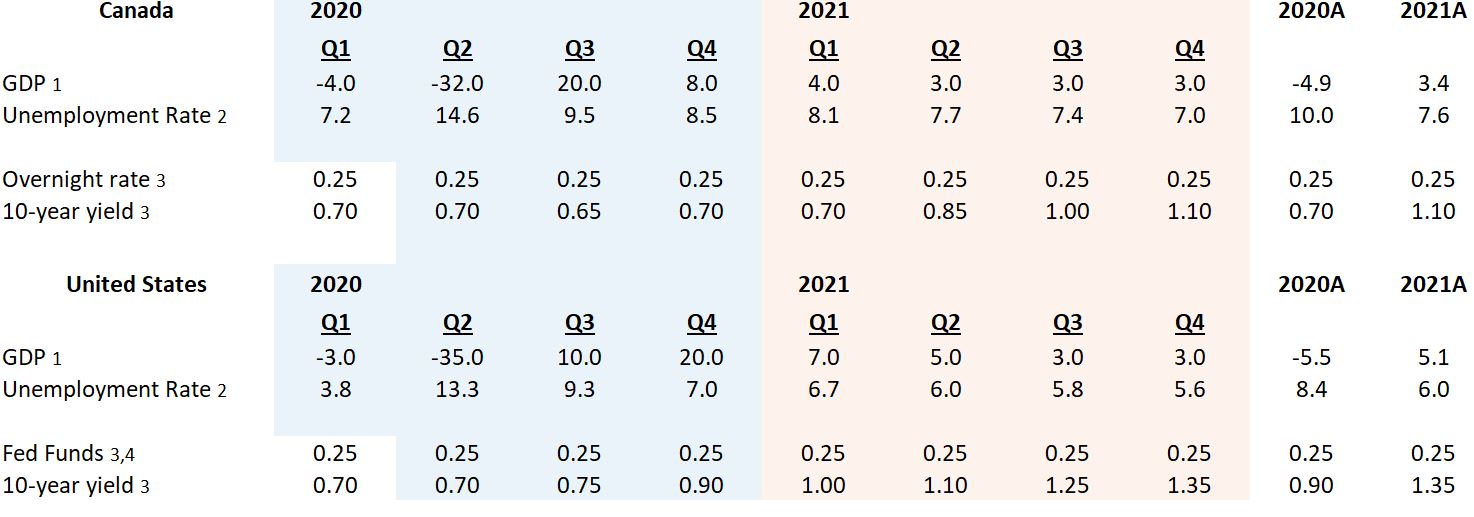

Economic forecasts

1 – QoQ annualized % change | 2 – %, period average | 3 – %, end of period | 4 – upper bound of 25 basis point range

Getting back to normal will be a gradual process

Some industries like education and public sector services should recover relatively rapidly with students returning to classrooms in September and demand for public services ramping up quickly once the worst of the coronavirus has passed. Other industries, like retail and food and accommodation services, will continue to face challenges. Canadians will initially be cautious about going out, and are likely to focus first on paying deferred bills and rebuilding their nest eggs. How quickly construction activity gets back online will be determined by the ability of homeowners to navigate through a period of heavy job losses.

Home resales are expected to fall 20% this year. Job losses, reduced work hours and income as well as equity-market declines will keep many buyers out of the market. Governments and banks have policies in place to help owners through this tough patch which should limit forced-selling and a glut of properties coming onto the market. But that doesn’t mean prices won’t come under downward pressure. As in many other industries, we expect the recovery in housing will be gradual. Low interest rates will be a stabilizing force, though it will take a rebound in the labour market as well as a pickup in immigration before sales really accelerate. Our view is that most of the recovery will occur in 2021.

2020 will be a year for the record books

Canada is likely headed for the deepest economic downturn on record (going back to 1961). The hit to the economy was quick and powerful, and even with the recovery expected to start in the third quarter, real GDP is forecast to fall by almost 5% this year. Canada will just barely outperform the US where policies to limit the virus’ spread were slower to materialize and the economy is projected to contract by 5.5%. Even with government policies aimed at supporting workers, unemployment rates are headed higher. Reports that claims for employment insurance are surging points to unemployment running in double-digits in the near term. In Canada, the government’s wage subsidy program (government will pay 75% of wages of workers at companies where revenues have fallen at least 30%) may limit how high the unemployment rate stays once the program is rolled out. Still, Canada’s unemployment rate will likely average 14½% in the second quarter and ease toward 8% by year-end.

While the headline numbers will look ugly, they will mask a serious increase in underemployment as workers are paid to stay home either by their companies or the government’s wage subsidy program.

Policymakers are all in

The Bank of Canada cut the overnight rate by 150 bps in March to 0.25%. It’s also purchasing a myriad of securities from government of Canada bonds to commercial paper and provincial securities, all to ensure financial markets provide stable, affordable credit to borrowers. While the traditional role of monetary policy supporting the economy through low interest rates may be taking a back seat to newer measures, low rates will become much more important once the economy is on the path of recovery. Early indications suggest the central bank’s interventions are having success at preventing real-economy disruptions from turning into a broader credit-market meltdown.

The federal government also announced an avalanche of income and wage supports aimed at supporting businesses and households during the peak of the crisis. Like the central bank, the government’s actions were aggressive, totaling $105 billion in direct support, largely to workers, combined with lending programs and tax deferrals for business. All told, the government support measures add up to 11.5% of GDP making the entire package one of the largest of the developed countries.

Biding our time

With the pandemic still unfolding, we don’t know how long tough economic conditions will persist. But it appears likely that measures to contain the coronavirus will be unwound gradually, pointing to a similarly gradual return of economic activity. This points to the recovery looking U-shaped rather than V-shaped. And some sectors of the economy, like oil and gas, are headed for an even slower recovery.

RBC Chief Economist, Craig Wright, joins the 10-Minute Take podcast to share his latest macro forecast.

Read report PDF

RBC Economics provides RBC and its clients with timely economic forecasts and analysis.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More