The threat of U.S. tariffs on Canadian imports has put Canada’s strong dependence on trade into sharp focus. Disruptions or restrictions to the flow of goods and services across the U.S. border could seriously harm Canadian businesses and communities—and ultimately—the broader economy. While there’s considerable uncertainty about whether tariffs will be imposed, and if so, at what rate and on which products—some industries and regions are more exposed to losing access to the U.S. market.

Canadian oil and gas producers, and manufacturers of primary metals, plastics, motor vehicles, and aerospace products are among the top industries most exposed to potential U.S. tariffs. If sweeping tariffs are implemented, it could create significant challenges to communities in Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and New Brunswick.

Energy and manufacturing industries heavily depend on U.S.

Canada is highly reliant on trade with the U.S. Domestic merchandise exports to the U.S. totalled $548 billion in 2023, accounting for nearly 77% of Canada’s total exports. Energy exports ($166 billion) and motor vehicles and parts ($82 billion) are the largest, and represent more than 40% of Canada’s total exports to the U.S.

These industries export substantial shares of their goods relative to total production, underscoring their heavy dependence on the U.S. market. That includes raw material exports like oil and gas where increased tariffs would more likely raise costs for U.S. consumers and producers than reduce imports from Canada. The newly expanded Trans Mountain pipeline has opened access to offshore markets, but 88% of Canadian energy exports still go to the U.S.

In heavily integrated manufacturing industries like the motor vehicle sector and metal manufacturing, the economic consequences of even modest tariff increases would be amplified by the deeply integrated nature of Canadian and U.S. manufacturing chains, where intermediate goods cross the border multiple times before becoming final products. This could have a compounding effect once tariffs are implemented, amplifying the total economic impact on both countries.

Together, top exporting industries in these sectors (by share of gross domestic product) collectively account for nearly 7.4% of Canada’s GDP. That’s more than the share of the country’s entire finance and insurance sector.

Additionally, trade disruptions would pose challenges to Canada’s labor market, especially in trade-sensitive industries. There are an estimated 2.4 million jobs tied to industries that export to the U.S., representing 12% of Canada’s total workforce.

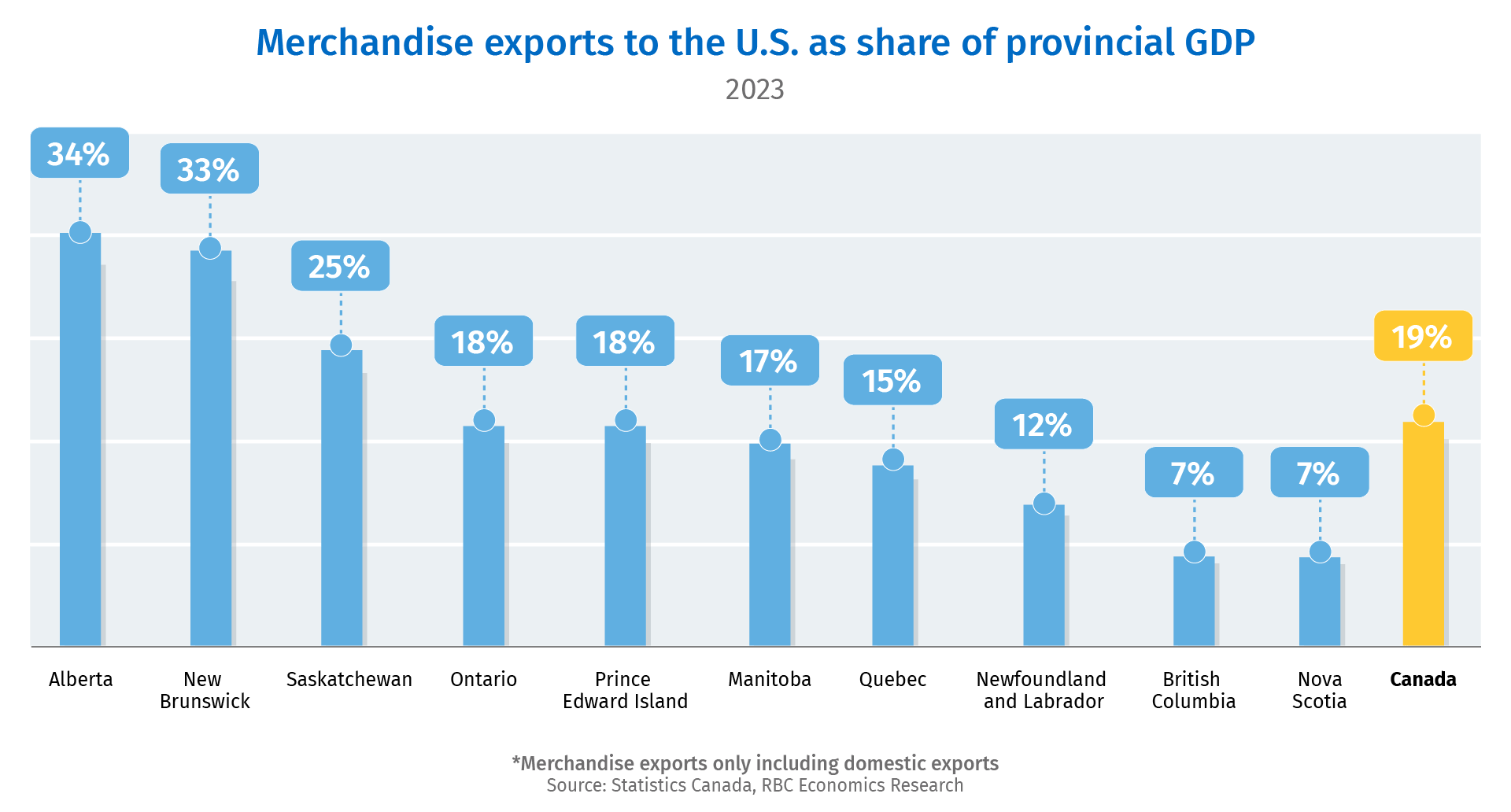

Provinces most at risk from U.S. tariffs

Exposure to U.S. tariffs will vary across Canadian provinces. Manufacturing-focused provinces like Ontario and Quebec would see significant challenges in motor vehicles and parts, metals, and aerospace industries. Any impacts to energy-exporting industries would largely be concentrated in Alberta, Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador. Ontario, Quebec, Alberta, and New Brunswick’s exports to the U.S. account for over 70% of their total exports, making them particularly sensitive to economic shocks arising from tariffs.

Energy exports from Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador, and British Columbia’s forestry sector would also see disruptions, but their overall exposure is somewhat mitigated by a smaller share of exports going to the U.S.

The economic impact of tariffs would extend beyond trade-dependent industries, creating broader implications for the economy. Tariffs rarely provide sustained net economic benefits, especially in closely integrated countries like Canada and the U.S. While low tariff rates may have minimal effects, higher rates could severely disrupt supply chains, amplify economic uncertainty, and trigger retaliatory measures, significantly affecting both countries.

Salim Zanzana is an economist for RBC. He focuses on emerging macroeconomic issues, ranging from trends in the labour market to shifts in the longer-term structural growth of Canada and other global economies.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.