Key findings

International students are a pillar of Canada’s immigration strategy, amid a structural demographic squeeze. Annually, about 17% of all new permanent residents and almost 40% of immigrants in the economic category have prior Canadian study experience1.

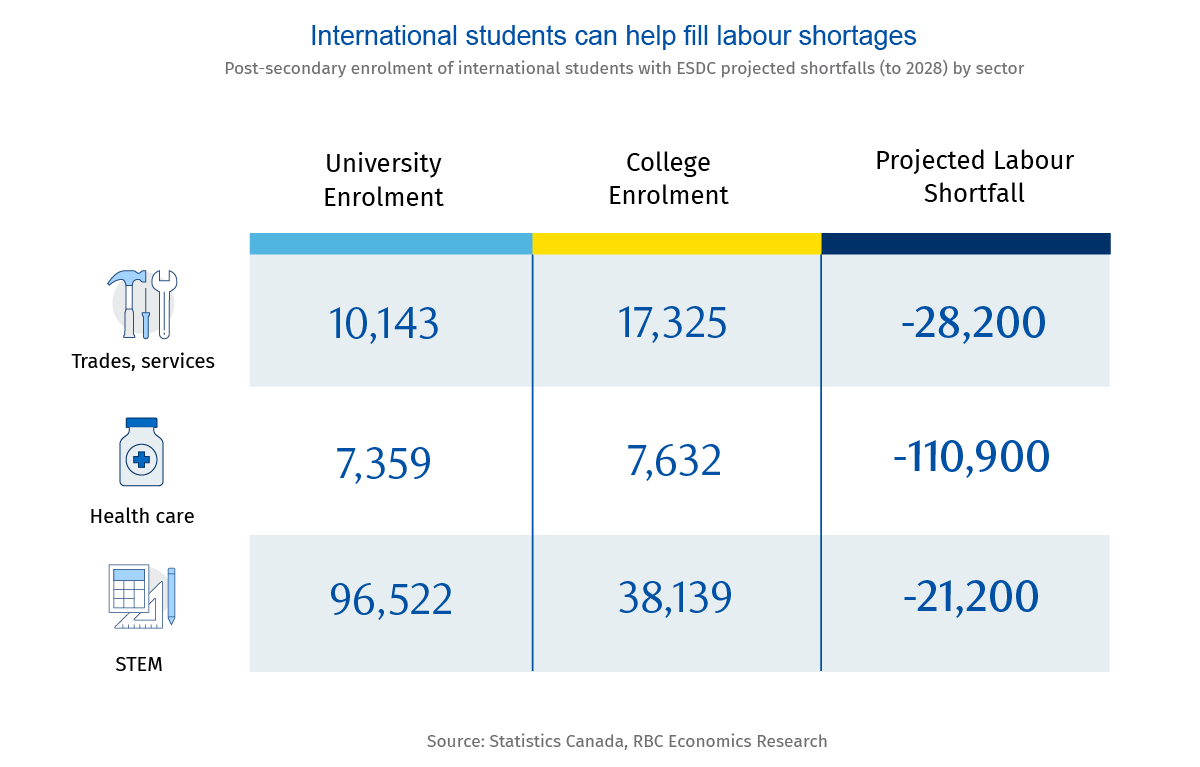

They are a rich source of highly-skilled global talent. International students are twice as likely as domestic students to study engineering and more than 2.5x as likely to study math and computer sciences―two top areas of projected labour shortages.

Canada is a top 3 global exporter of education services. International students have also emerged as an important funding source for Canadian post-secondary institutions, which play a big role in selecting foreign applicants. While representing less than a fifth of university enrolments, foreign students account for a third of tuition fees paid.

The mix of international students is changing, potentially affecting future labour market matches and concentrating Canada’s source countries. International student enrolment in public and private colleges has grown almost twice as fast as those at universities. But many students may not be market-ready and have long, drawn-out paths to permanent residency—if at all.

Labour market misalignment and a perplexing immigration system could diminish our ability to keep international talent. Foreign students are underrepresented in health care and trades, and few are able to acquire the same level of early work experience as domestic students.

Global competition for high-calibre international students is intensifying, as Canada’s peer countries and new competitors sharpen their immigration policies to support their talent-hungry employers.

Canada’s classroom-to-citizenship process needs an urgent reset

Thousands of foreign students pass through the gates of Canadian universities and colleges every year, armed with skills essential to succeed in the new economy. The unsubsidized tuition fees they pay are now a lucrative revenue source for our post-secondary institutions and helped burnish Canada’s reputation as a global place of learning.

International students are also considered ideal candidates for permanent residency to replace an aging workforce. Canada’s immigration system has been alive to the issue, prioritizing economic class permanent residents (i.e., new immigrants) with skills needed in the labour market. International students are now a key talent pipeline, representing almost 40% of new economic-class immigrants.

But as the global war for talent escalates, Canada needs to sharpen its policies to maintain its edge. The country’s recent health care staff shortages are a wake-up call that Canada should be more strategic in leveraging and expanding its international student pool. Looming shortages in STEM, trades and skills needed for the new green economy already hover over the horizon. Can we synthesize our international education and immigration strategy to set out a clearer path for international students eager to lay down their roots in Canada?

The various stakeholders (at all levels of governments, education institutions and employers) must collaborate on strategies that prevent promising talent from slipping through our fingers.

The economic value of immigrants coming through the education route is sizeable and reverberates across the wider economy: Among immigrants admitted in 2018, study and work permit holders obtained median wage of $44,600 within a year, compared to $25,700 for immigrants without Canadian work or study experience2—and this earnings outperformance has grown larger over time.3

Amid tight labour markets, other countries have also renewed their efforts to retain students with the right skillsets. With the number of international students set to surpass 7 million globally annually by 2030, compared to nearly 5 million today, advanced and emerging economies are eyeing ways to educate and keep the best talent.4

Canada risks losing its shine as other destinations beckon top international students pursuing STEM and other programs such as healthcare and trades. As top-tier talent becomes more elusive, the pressure to attract and retain them will escalate.

School’s in: Canada is the world’s classroom

Canada is an international education powerhouse, recently surpassing the UK to become the third largest destination for international students after the U.S. and Australia. On a per capita basis, we are only outpaced by Australia among major education hubs.

It’s big economic value. Educating foreign students in Canada is a services export. Canada is a top 3 global exporter of education services, with the sector representing about 12% of Canada’s services exports in 2019. International students also contributed over $22 billion to the Canadian economy and supported more than 218,000 jobs in 2018.5

“I was considering the UK and Australia for higher education but ended up choosing Canada as it was the easiest to get residency.”

Kumara, international student from Sri Lanka

Kumara, international student from Sri Lanka

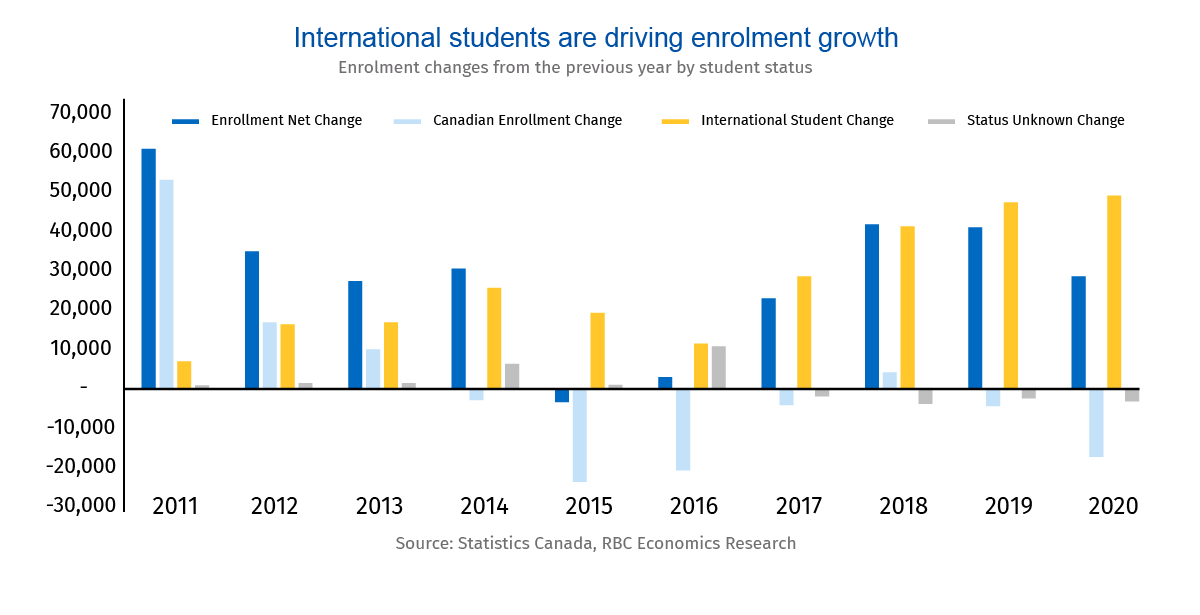

Enrolment of international students at Canadian post-secondary institutions (PSI) has grown from 7.2% in 2010 to almost 20% in 2020. Since 2016, PSI enrolment growth has been entirely driven by international students.6

How did it get this way? For one, Ottawa’s decision in 2016 to increase the weight given to Canadian education in the points system for permanent residents raised the country’s profile as a global immigration-via-education hub: a recent international survey of students looking to study abroad showed 39% of respondents list Canada as their most desirable destination, the highest of any country.

“Recruiting immigrants through education pathways is a very effective way to integrate new Canadians and set them up to do well here.”

Matt Hebb, Vice-President, Government and Global Relations, Dalhousie University

Matt Hebb, Vice-President, Government and Global Relations, Dalhousie University

Secondly, foreign students’ unsubsidized tuition fees have become a vital source of revenue for Canada’s designated learning institutions, or schools that can accept international students. As domestic tuition fees stagnate and per student public funding declines across many provinces, DLIs are tapping the rich pool of international students eager for a Canadian education. International students represented about a fifth of the student base, but over a third of tuition fees received by Canadians universities in 2018/2019, with fees on average three times that of domestic students.

CHANGING MIX

With these policy changes and embedded incentives, Canada has seen a shift in the mix of international students. While these changes are a reflection of Canada leaning into one of its immigration objectives—to be a global education hub—they may come at the cost of the primary one—to attract and retain international talent.

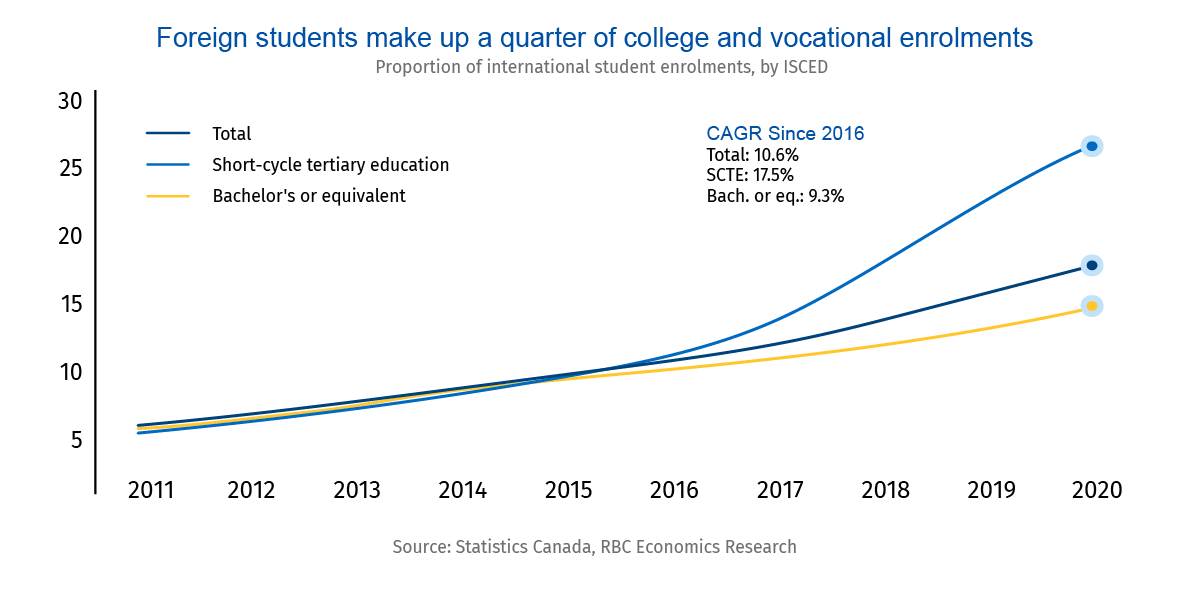

Greater numbers of international recruits from colleges may also give the impression of a nearly-ready pool of students that can get on the immigration fast-track. Enrolment in short-cycle post-secondary programs―more common in public or private colleges and as short as 8 months―have grown twice as fast as other programs since 2016, when increased international demand gave colleges a new growth avenue. One in 9 students in Canadian short-cycle programs were foreign-born in 2016, compared to 1 in 4 in 2020.7

“Colleges and institutes develop programs in consultations with program advisory committees that are made up of people in the community. It means whatever is taught in colleges and institutes is in line with regional labour market needs.”

Denise Amyot, President and CEO, Colleges and Institutes Canada

Denise Amyot, President and CEO, Colleges and Institutes Canada

THE FLIP SIDE

A few unscrupulous private colleges were recently accused of deploying questionable methods to recruit international students. Though rare, it highlights the importance of maintaining the integrity of Canada’s education system.

Many international students may also not understand the challenges of dealing with Canada’s high cost of living, labour market, or complicated work permits system. This misalignment of expectations could undermine Canada’s international reputation. Some private career colleges have been singled out for these issues, including by Ontario’s Office of the Auditor General for not protecting students.

Canada needs college-educated students to address labour shortages across the economy. But some students in short-cycle programs have a longer route to the labour market and permanent residency, and some may not have a path at all. With colleges now taking in 40% of Canada’s post-secondary international students, versus 24% in 2010, their admission choices are material to Canada’s foreign talent pipeline.

To address the skills gaps, many colleges and universities are teaming up with corporations, municipal and provincial governments to create training and bridging programs that are more sensitive to labour market needs. But there is need for a more concerted policy shift to narrow the gap.

STRENGTH IN DIVERSIFICATION

Canada has also seen a shift in the source countries of its students. Post-global financial crisis, the number of Indian students studying in Canada started to grow, with the trend taking off post 2016. In 2017, India surpassed China as the dominant home country of Canada’s international students, with almost 34% of all international students coming from India. The number of study permit holders from India surged 270% from 2015 to 2020, compared to a 0.76% drop among Chinese students.8

Today around 56% of Canada’s international students are from India and China. Canada’s lack of diversification in student source countries exposes its talent pipeline and services exports to market and geopolitical risk (such as when Saudi Arabia pulled its students in 2018 after a diplomatic row with Canada). Public policy has started to recognize this challenge, introducing the Student Direct Stream in 2018, a faster permitting process for students from 14 countries including Pakistan, Philippines and Vietnam, which incentivizes DLIs to broaden its student base. It’s still too early to determine whether the SDS has altered the mix of students coming to Canada.

“Institutions are the ones principally selecting people. And federal and provincial immigration programs are operating on the side and saying, ‘how do we get some of these people to stay?’”

Iain Reeve, Associate Director, Immigration Research, Conference Board of Canada

Iain Reeve, Associate Director, Immigration Research, Conference Board of Canada

Life after school: Path to immigration

There’s a global war for talent.

Canada’s peers are sharpening their policies. The US remains a magnet for international students given its Ivy League universities and job opportunities. Proposed changes to US immigration laws also make it easier for STEM students to enter and stay in the country. The UK has launched a campaign to attract high-calibre international students. Australia also rolled out a 10-year strategy in 2021 to better align its international educational offering with employment opportunities and diversification of source countries.

Across the world, skills in areas as diverse as STEM, healthcare, education, green jobs and advanced manufacturing are being prized more than ever before, and India, China, Malaysia and Singapore are among the growing pool of countries looking to attract, educate and retain knowledge workers.

Getting international students in the door is the first step in the immigration process as they develop skills, culture, language and networks that make them more likely to stay in the country. But getting them to stay often hinges on what happens as school ends and students eye their pathways to careers and permanent residency

“We need a ‘Team Canada’ approach to marketing the country as an education destination – not just in terms of dollars, but in engaging with Canadian enterprises and civil society organizations that have deep roots in countries and regions we’re targeting.”

Paul Davidson, President, Universities Canada

Paul Davidson, President, Universities Canada

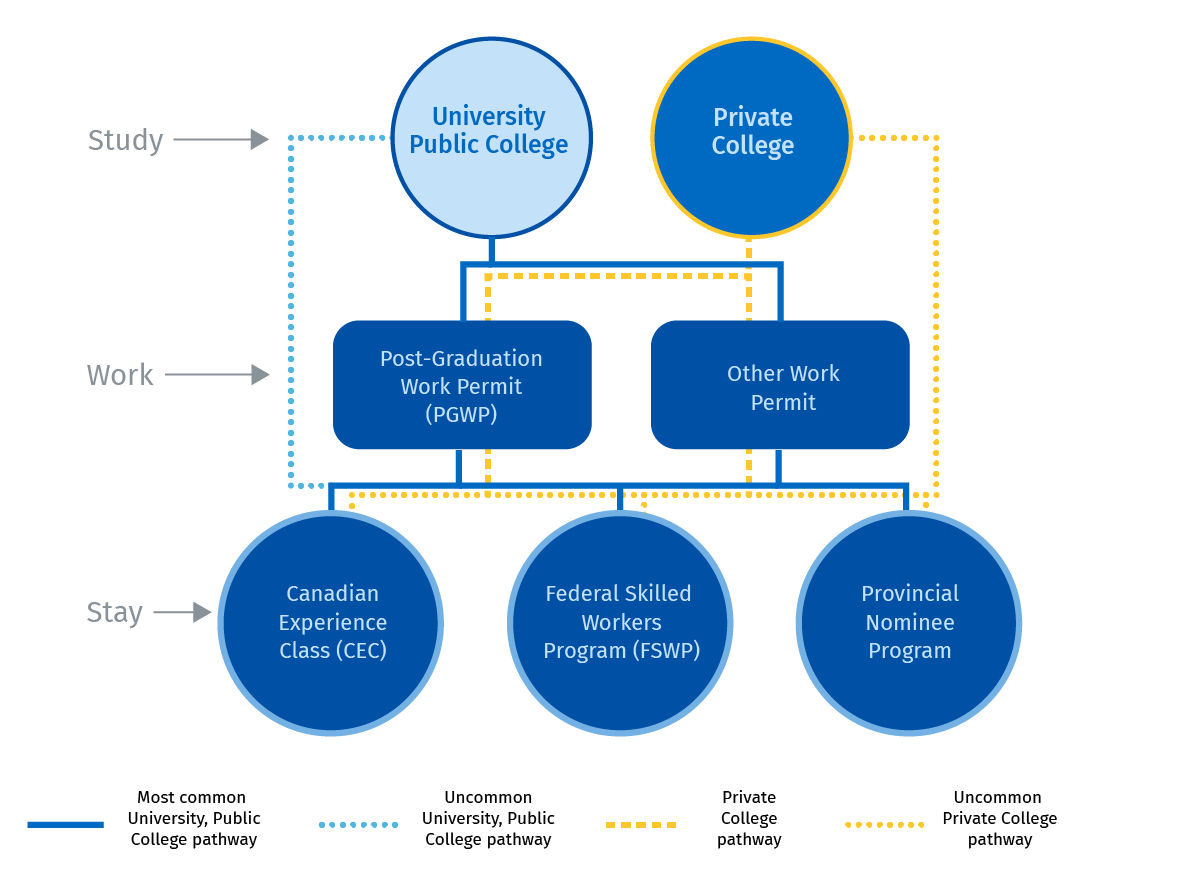

PREPONDERANCE OF PATHWAYS

Canada has been a global leader in creating a clearer pathway for many international students toward permanent residency. A number of programs, including the Post-Graduation Work Permit (PGWP), has made it easier for international students to gain work experience in the country and start working without waiting for (often lengthy) permit processing. It was designed to keep international students in Canada and accelerate their entry into the labour market, helping them accumulate experience that would strengthen their permanent residency application.

Since then, the PGWP has become a key building block for student immigration pathways. More than 157,000 former students became permanent residents in 2021, with more than 88,000 transitioning directly from a PGWP9. An RBC survey of international students found that 39% had already applied for a post-graduate work permit, while another 55% said they intend to apply for one.

But the PGWP does not apply to everyone―students in many private college programs are not eligible. It is also time-limited depending on length of study. To gain enough points for permanent residency, a student would have to string together any number and combinations of study and work permits. Yet, some can transition to permanent residency direct from a PGWP or student visa—there are numerous unique pathways.

Once they finish school, thousands of international students find themselves lost in this labyrinth that is the road to permanent residency. Even for students that have strong credentials, navigating work and study permits and extensions, or deciding which permanent residency stream to pursue, can be daunting due to lack of guidance and their prospective employer’s reticence to navigate the immigration system. Some students use immigration lawyers or advisors. Many post-secondary institutions offer services to help bridge some of these gaps, but there are capacity limitations.

Trouble in navigating a complex system adds to student stress and could deter many students from pursuing their Canadian dream. Perceptions of a complex and bureaucratic immigration system can influence their decision to remain in Canada.10 These are costly misses for Canada that needs a steady pipeline of skilled citizens to ensure its continued prosperity.

“The pathways are complex, dynamic, and constantly evolving, which is great. But trying to stay on top of these pathways such that you can actually leverage them can be very, very challenging.”

Larissa Bezo, Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Bureau for International Education

Larissa Bezo, Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Bureau for International Education

Campus to corporate life: Students in the workplace

Obtaining a work permit is an important immigration step, but relevant labour market experience is a decisive factor in obtaining permanent residency.

Canada’s 10-year conversion rate of international students to permanent residents is 33%, based on the cohort that started in 2010. For the PGWP, the comparative rate is 73%11. The increased use of the PGWP since 2008 should increase Canada’s overall retention rate as more recent 10-year stats become available. But a key question is whether Canada is doing enough to recruit and retain international students that align with our labour market needs.

While international students pursuing expensive but in-demand study programs can often see a path to high-paying jobs within Canada, a sizeable number of students struggle to realize their full economic potential. Migrating to Canada through the student pathway is also a more expensive route compared to other channels. The average undergrad tuition fees at universities for international students is $33,000 annually for international students, compared to $15,500 in total for those migrating to Canada through other immigration channels. For many, a Canadian education may not yield the desired return on investment.

STRESSED STUDENTS

Despite living with her brother, 19-year-old Suong feels “totally isolated,” and struggles to adjust to her environment. The human resource management student also says limited interaction with the wider Canadian society has added to her loneliness.

Other pressures can amplify this feeling. While Canada’s steep housing, transport and other living expenses are not unique to international students, surveys show this cohort feels especially stressed due to limited funds and lack of work opportunities. Depression among international students is common and often exacerbated due to lack of adequate health insurance.

LABOUR MARKET DISCONNECT

International students’ disconnect with labour markets has emerged as a weakness in the classroom-to-permanent residency process. For one, there is some misalignment between the study programs pursued by international students and labour market needs.

Foreign students are well-represented in STEM and Business Administration. They are twice as likely as domestic students to study engineering and more than 2.5x as likely to study math and computer sciences―two top areas of projected labour shortages. However, their numbers need to rise in healthcare, some trades and services, and education to meet Canada’s future labour market needs. An RBC report last year estimated up to 400,000 green collar jobs would be required to transition Canada’s economy by 2050.

“The labour market and international education are not aligned well yet and we are not benefitting fully from the real power international students. With some adjustments to create the alignment, Canada can really benefit at scale.”

Martin Basiri, Co-Founder & CEO, ApplyBoard

Martin Basiri, Co-Founder & CEO, ApplyBoard

More use of specialized fast-tracked visa streams increasingly used during the pandemic can signal priority fields of study to prospective international students, but a more deliberate process may be needed to ensure international students are represented in fields with future labour market opportunities.

Lack of work experience acquired during studies has been cited as a primary barrier to international students finding a job after they graduate12. While this is a common challenge for many students, international students face explicit barriers to acquiring work experience. Study permits limit their holders to 20 hours of off-campus work per week (on-campus work is uncapped). The rule is in place to ensure those with a study permit make education their priority and protect Canada’s education and immigration systems from potential abuse.

Given tight labour markets, a case can be made to show some flexibility that allows international students to secure meaningful Canadian work experience in their field of study and also alleviate Canada’s skills shortage. Studies show that visible minorities who participate in co-op programs earn larger returns than their white male peers and report feeling more connected with their broader community13. The Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration has suggested that providing work permitting exemptions for academically-qualified international students in need of financial assistance should be considered.14

International students are also ineligible for most government-funded and other Work Integrated Learning (WIL) programs. The Business + Higher Education Roundtable (BHER) has been successful in prompting employers to create a wider range of opportunities for domestic and international students. The federal government is also providing nearly $1.4 billion in funding to create additional 350,000 domestic student work opportunities over five years.

International students are ineligible for most of these programs, regardless of their field of study or whether or not they’re partaking in a co-op program for academic credit. That’s a critical obstacle, as businesses are wary of hiring international students without a streamlined official process. A Business Council of Canada and BHER survey found that over a quarter of businesses cited difficulties navigating the immigration system as a barrier to recruiting and retaining international talent.15

Next level: A strategy for the next decade

It’s hard to find disagreement on the importance of international students to meeting Canada’s immigration targets and economic challenges. And many recognize the value of international students in supporting world-class Canadian post-secondary institutions.

But collaboration and policy coherence are lacking, leading to high concentration risk from foreign student source countries, threats to system credibility when students do not understand their pathways to the labour market or challenges of living in Canada, limited support to navigate a complex immigration system that leaves students more likely to opt out, and lack of labour market alignment or early work experiences that belie the labour market integration Canada’s policy hopes to achieve.

Canada needs a targeted approach to sustainably grow its education sector and effectively leverage its international student population as a future source of labour and permanent residents. Focusing on in-demand fields of study, increased transparency in the permitting process, streamlined pathways, and more robust public and private sector support would ensure Canada does not lose out on the benefits promised by Canadian-educated immigrants.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Ottawa should consider setting three-year targets for the number of international students and provide guidance on work study programs that more closely align with the skills needed by provincial governments and employers.

Provinces should develop a 10-year funding framework for post-secondary institutions that allows them to focus on a market-sensitive education structure that is attractive to, but not overly dependent on, international students.

Expand the share of immigrants with Canadian study experience within the economic immigrant class with special emphasis on STEM, healthcare, and in trades that are vital for energy transition. Ottawa could invest around $50 million in a pilot wage-subsidy program for 7,000 foreign students in high demand fields.

Governments and post-secondary institutions should work together to expand career, health and settlement support services that ensure student well-being and boosts their chances of success.

The federal government should collaborate with other parties to create a portal that transparently lays out the policies, pathways and eligibility requirements to study, work and stay in Canada.

Post-secondary institutions could commit to the diversification of source countries, with special emphasis on setting loose targets from the Student Direct Streams. Colleges and Institutes Canada and Universities Canada can help in identifying new source countries. Canada should also tap its free trade agreement partners.

All organizations, including employers, should enable more work integrated learning opportunities for international students. Specifically, the federal government could exempt students from needing an additional work permit for co-op terms and internships. BHER has been successful in prompting employers to create a wider range of opportunities for both domestic and international students, but other stakeholders could develop programs that better integrate students with work-integrated learning opportunities.

Ben Richardson, Research Associate, RBC Economics & Thought Leadership

Yadullah Hussain, Managing Editor, Climate and Energy, RBC Economics & Thought Leadership

Cynthia Leach, Senior Director, RBC Economics & Thought Leadership

Darren Chow, Senior Manager, Digital Design, RBC Economics & Thought Leadership

Zeba Khan, Manager, Digital Publishing, RBC Economics & Thought Leadership

Aidan Smith-Edgell, Research Associate, RBC Economics & Thought Leadership

1. Statistics Canada, 2021; IRCC, 2022

2. Statistics Canada, 2021, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/211206/dq211206b-eng.htm

3. Statistics Canada, 2022, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/36-28-0001/2022002/article/00004-eng.htm

4. Export Development Canada (EDC), 2022. https://www.edc.ca/en/weekly-commentary/canada-competitive-business-environment.html

5. https://www.cicnews.com/2020/02/642000-international-students-canada-now-ranks-3rd-globally-in-foreign-student-attraction-0213763.html#gs.73dw88

6. Statistics Canada, Postsecondary enrolments by student status (ISCED), 2021

7. Statistics Canada, Postsecondary enrolments by ISCED, 2021

8. IRCC, Study permit holders by country of citizenship, 2022

9. IRCC, 2022, https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2022/04/new-measures-to-address-canadas-labour-shortage.html

10. Nieterman et al. “Should I Stay of Should I Go? International Students’ Decision-Making About Staying in Canada. 2021. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12134-021-00825-1

11. Statistics Canada; Choi, Y., E. Crossman, and F. Hou. 2021. “International students as a source of labour supply: Transition to permanent residence.” Economic and Social Reports

12. Canadian Bureau of International Education, 2022. https://cbie.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/CBIE-2021-International-Student-Survey-National-Report-FINAL.pdf

13. C.D. Howe, 2020. https://www.cdhowe.org/public-policy-research/work-ready-graduates-role-co-op-programs-labour-market-success

14. Standing Committee on Citizenship and Immigration, 2022. https://www.ourcommons.ca/Content/Committee/441/CIMM/Reports/RP11800727/cimmrp08/cimmrp08-e.pdf

15. Business Council of Canada, 2022. https://thebusinesscouncil.ca/report/empowering-people-for-recovery-and-growth/

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In addition to those cited in this report, we thank the following individuals and organizations for their insights:

- Rupa Banerjee, Canada Research Chair and Associate Professor, Human Resource Management/Organizational Behaviour Dimensions Faculty Chair, Ted Rogers School of Business Management, Toronto Metropolitan University

- Matt McKean, Chief R&D Officer, The Business + Higher Education Roundtable

- Peter Scott, President, Athabasca University

- Cynthia Ralickas, A/Director, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Louis Arsenault, Vice-Principal, Communications and External Relations, McGill University

- Kyle Budge, President, Sheridan Students Union

- Abhay Bhingradia, (Catarina) Nguyen Phuong Khanh Pham, Om Patel, Sanjey Sureshkumar, international students

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.