Energy. Geopolitics. Trade.

All three topics were on full display at Columbia’s Global Energy Summit 2025. Tariffs and trade policy dominated the Summit, with significant implications to both the supply and demand of North American energy. Shaz Merwat, Energy Policy Lead of RBC’s Climate Action Institute, was in attendance and shares the five most pressing themes at this year’s event.

1. Energy risks becoming more complex

The push to re-orient trade flows to manifest specific economic outcomes (reduce a trade deficit, reshore production) likely increases price risk through a bifurcation of supply and demand in key commodities. At the most obvious, tariffs levied on steel, aluminum and possibly copper–all key inputs to energy infrastructure–result in regional pricing. As seen in the chart below, U.S. aluminum prices have largely decoupled from European pricing as a result of Trump’s tariffs. Similarly, price differences between U.S. Midwest hot rolled coil steel prices (US$1,075/tonne) and Northern Europe hot rolled coil steel (US$715) has increased to about $360/tonne, compared to $150/tonne at the start of the year.

Geopolitically, risks are also expanding beyond the simple ‘Middle East’ supply risk that we have known for the last half century. Spheres of influence can re-orient supply and demand relationships, especially in the case of LNG and critical minerals. These emerging geopolitical trade barriers ultimately weaken an otherwise more ‘global’ market to absorb supply and demand shocks–which likely are more deliberate at a time when weaponized trade is becoming increasingly more common (Russian gas, Chinese supply chains, the American market).

2. What is this energy dominance you speak of?

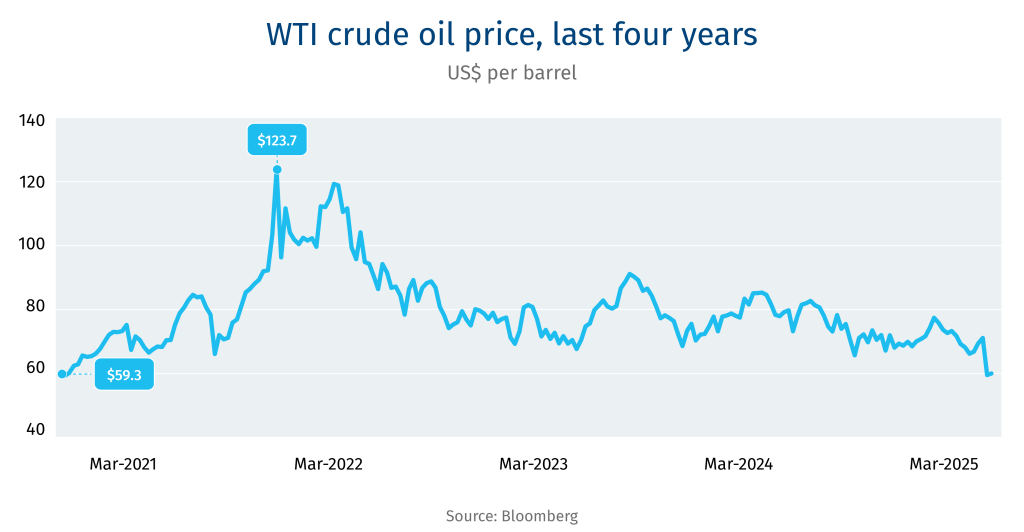

While the Administration has vowed to unleash U.S. energy dominance, to date, it appears to have done the exact opposite. On oil, Trump’s trade/tariff agenda has driven oil prices lower than those witnessed for most almost all of Biden’s presidency. WTI has twice dipped below US$60 per barrel in the past week–a level widely seen as U.S. shale’s breakeven–leading to increasing concerns of idled rigs and declining production; S&P Global estimates US$50/bbl oil could cause a U.S. production decline of 1 million bbl/d. All the while, OPEC is boosting production.

The continued desire to gut funding for the Inflation Reduction Act also stymies U.S. renewable energy, even for tax credits deemed friendly to the oil industry (such as the 45Q carbon capture tax credits). Lastly, concerns around supply inflation (steel/aluminum tariffs) and general market/economic uncertainly has created a very challenging environment to deploy capital.

3. Climate trade frictions remain alive and well

With the gutting of the WTO and Trump’s reciprocal tariffs, developing nations are increasingly seeing their preferential trade terms (higher ‘allowable’ tariff rates) erode. You can add climate to that list, as nations impose climate-related trade measures to enhance economic competitiveness.

In Europe, carbon border adjustments protect domestic carbon policy. In the U.S., a border pollution fee leverages America’s carbon advantage–especially in relation to China. The U.K. and Australia are also exploring carbon border adjustments of their own.

Domestic carbon policies without a climate trade measure (such as a CBAM), politically, is almost certainly bound to fail. Yet, expectations for developing nations to enact similar carbon prices as the E.U.’s emissions trading scheme–a system that has seen carbon pricing increase/expand over the last two decades–in a mere few years, seems unjust. This likely only accentuates climate trade tensions between North and South.

4. Reducing the trade deficit

In the eyes of U.S. President Donald Trump, reciprocal tariff rates yield a balanced trade relationship. For trade partners, a balanced trade relationship is as good as a ‘due north’ one can expect under Trump’s vision of America First. Trade partners will be served well if they can better house American (merchandise) exports.

In this world, U.S. LNG likely shines bright. The country is expected to surpass Qatar as the largest provider of U.S. LNG, globally, by 2030 according to RBC Capital Markets forecasts as seen below. For major LNG buyers that run large trade surpluses with the U.S. (the E.U., Japan, Korea, India), greater purchases of LNG supply can be the ‘easy’ win.

5. AI clusters and cross-border data flows

Nations with abundant, cheap electricity are best positioned in the race to build data centers. This likely results in supply ‘clusters’, especially torqued to renewable generation given the climate commitments of tech firms. Consensus is increasingly pointing to Canada, the U.S. and the Middle East as becoming cluster of American artificial intelligence deployment.

But what does that mean for data flows? Data protectionism towards data hosting (colocation) likely remains, but more alignment is needed on cross-border data transfers resulting from compute capacity (hyperscale). We expect more on this in the renegotiation of USMCA in 2026.

Shaz Merwat is the Energy Policy Lead of RBC’s Climate Action Institute

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/our-impact/sustainability-reporting/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.