- Older millennials (and younger Generation Xs) have seen their liabilities balloon to record levels.

- And while earnings have grown rapidly, they aren’t catching up fast enough to absorb higher debt payments.

- The burden is set to grow: average Canadians renewing their mortgages could see their monthly payments jump by ~25% by early 2024.

- And the current, elevated intake of newcomers is set to slow as the system catches up with pandemic disruptions.

- The bottom line: Though their consumption has remained resilient, heavy liabilities make Canadians in the middle of the age distribution most vulnerable to labour market shocks. If job losses rise in this group, strength in consumer activity will most certainly erode.

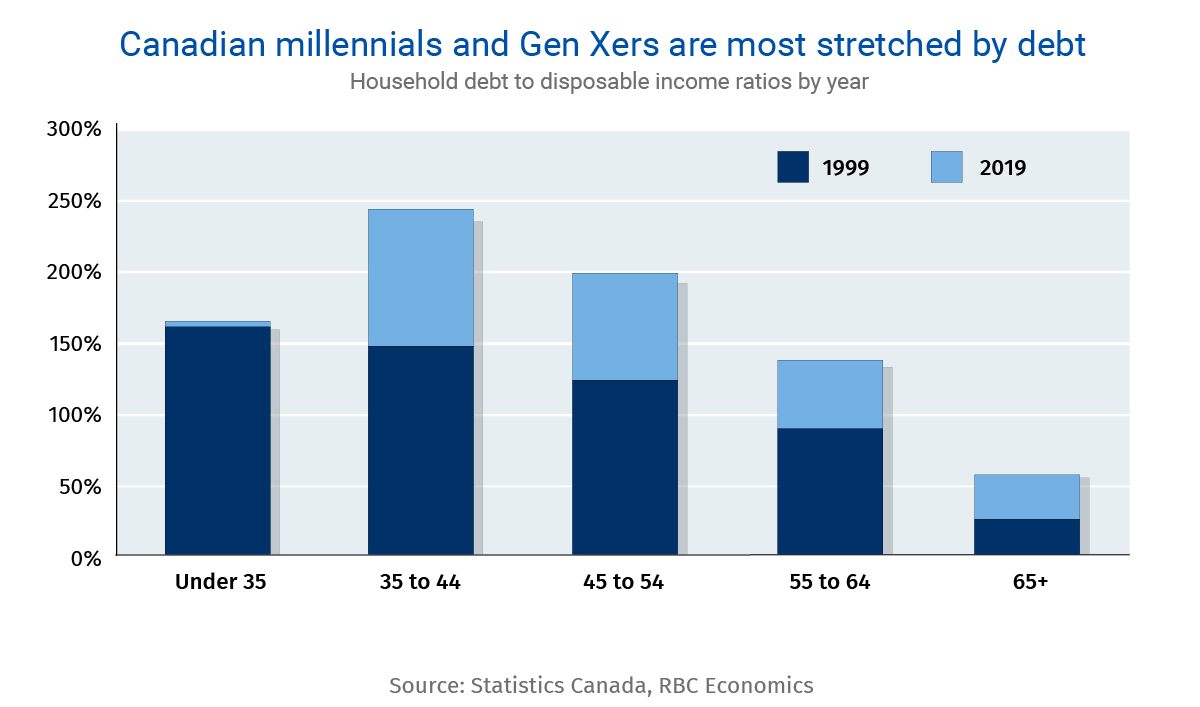

Millennials are more indebted than ever

The millennial generation has in many ways been defined by its staggeringly high household debt.

Canadians between the ages of 35 and 44 (who have debt) had a total debt-to-disposable income ratio of 250% in 2019. That’s far heavier than the debt load that was carried by Canadians of the same age in 1999 (~150%). Younger indebted millennials (under age 35) aren’t faring much better, with debt loads worth 165% of their disposable income. Surprisingly, this youngest cohort hasn’t seen its debt-to-income ratio rise materially since 1999, though its home ownership rate is much lower (only one-third have a mortgage).

Following a rapid round of interest rate hikes, Canadians renewing their mortgages1 in the near future could face a 25% increase in monthly payments. Not all millennials have mortgages. But for those that do, the impact on payments will be much more dramatic. This is especially the case for younger cohorts with higher remaining principals—particularly since earnings haven’t kept up with the pace of debt accumulation. Since the beginning of the pandemic, average hourly earnings have risen 12%, less than half the increase of the average five-year fixed mortgage payment.

Higher rates are a boon to many asset-rich boomers

Boomers—Canada’s largest cohort—are faring better. Those aged 65 and older account for nearly a quarter of tax filers and 20% of total household income. And as a general rule, this group is far less sensitive to interest rate hikes. That’s because only 14% of boomer households still have mortgage debt and for those that do, the average balance is half the size of a millennial mortgage. Boomers and older Generation Xs (aged 55 and up) have also amassed a bigger basket of interest-earning assets—which stand to benefit from a higher interest rate environment. Canadians’ personal term deposits in chartered banks have risen $200 billion above pre-pandemic levels, largely due to the lure of higher interest rates.

For Canadians aged 65 and older, employment income is also less important (accounting for a smaller share of their total income), as their assets insulate them from income shocks associated with job losses. Two-thirds of income for Canadians aged 65 and older comes from private pensions and government transfers. Only 16% is employment income.

Yet boomers tend to spend less

Despite these advantages, boomers’ consumption levels are the lowest on average. This group is spending over a third less on discretionary goods and services than younger Canadians in their thirties. And given younger cohorts’ heavy reliance on a stable employment income (which accounts for 85% of their total income) to service high debt levels, layoffs could significantly derail discretionary spending. While growth is still holding up even after record rate hikes, higher unemployment rates may trigger an entirely different outcome for demand in the year ahead.

Carrie Freestone is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group and is responsible for examining key economic trends including consumer spending, labour markets, GDP, and inflation.

Proof Point is edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

- Based on a five-year fixed rate mortgage with a 25-year amortization period. Rates are sourced from RateHub based on a change in average mortgage rates between January 2019 and January 2023.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.