- Canadians’ pandemic savings are still growing—rising to about $350 billion as of Q3 2022.

- But those savings continue to be unequally distributed, with higher-income earners socking away the lion’s share.

- Rising inflation and debt payments have already eaten into the more modest savings of lower-income households. That’s expected to continue as they borrow more to pay for essentials.

- The bottom line: With a recession looming, the asymmetry of savings will lead to a more dramatic period of pain for lower income Canadians. While the savings stockpile among high-income earners is unlikely to be spent, lower-income households will continue to be squeezed by a higher cost of living.

The huge trove of pandemic savings is still intact

In previous work, we found that Canadians had built a record amount of savings during the COVID-19 crisis. Thanks to a combination of government aid and fewer spending opportunities, household savings rose roughly $350 billion above pre-pandemic levels by the end of the third quarter of 2022.

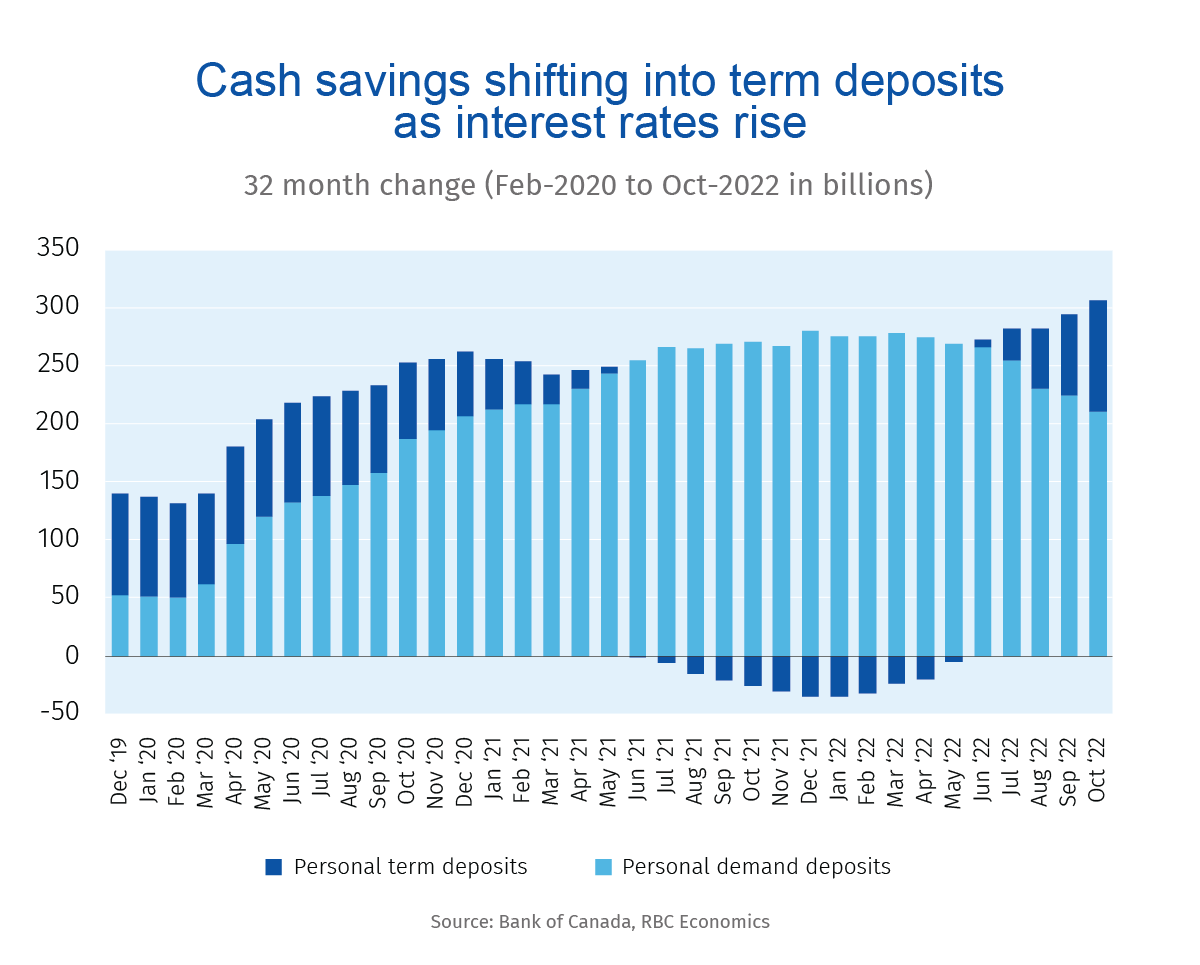

That pace slowed as government transfer programs faded and pandemic restrictions eased. But the pile of excess savings has yet to shrink. Chartered bank demand deposits (which allow immediate withdrawals) have started to decline. Yet instead of flowing to consumer spending, this money has shifted into term deposits (which lock away cash for longer terms but pay a bigger return due to higher interest rates).

That means the post-lockdown resurgence in Canadian household spending has been funded entirely out of earned incomes. This was enabled by a rapid recovery in labour markets in the first half of the year, which offset the wind down of government aid.

Soaring cost of living widened the savings gap

The cost of living for Canadian households will continue to rise. A decline in inflation only means prices will grow at a slower rate. And the delayed impact of interest rate increases in 2022 will continue to push household debt servicing costs higher, tightening the squeeze on household finances. Our current projection is for debt payments to rise to a record 16% of household disposable income by the end of 2023, leaving less current income for spending.

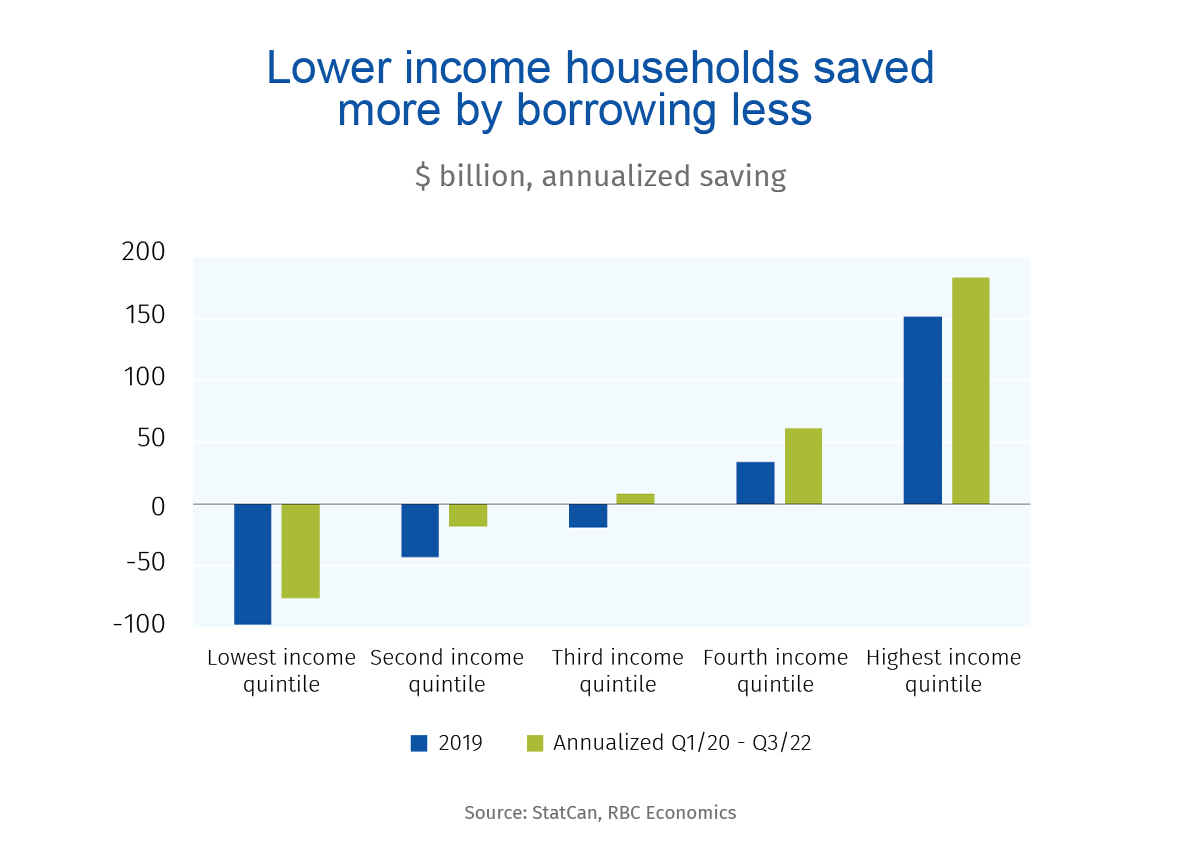

This dynamic will take the heaviest toll on lower income households—those with the smallest savings backstops. Indeed, rather than saving more during the pandemic, lower income households really just borrowed less. According to Statistics Canada, average savings per household among the lowest 40% of income earners were already negative in the first quarter of 2020. They fell another 12% below those levels by the third quarter of 2022 as the cost of living rose. By comparison, savings were up by 28% through the same period among the top 40% of income earners.

These higher-earning households will likely continue to save. Surging interest rates, a sharp pullback in housing prices, and lower financial market asset values have eaten into consumer confidence. And lower consumer confidence typically leads to more saving, not less. As we noted in previous work, household net worth —which spiked during the pandemic—is now shifting from a driver to a drag on spending growth. More than $1 trillion in assets were wiped out over the second and third quarters of last year as housing and financial markets retrenched. And though net worth is still running ahead of pre-pandemic levels, these factors have left Canadians feeling much less wealthy.

High levels of savings won’t prevent a recession

We still expect a ‘moderate’ recession in the first half of 2023 as central bank interest rate hikes cool an overheating economy. The latest Bank of Canada Business Outlook Survey has already shown signs of a deterioration in consumer demand. And the survey showed businesses expecting outright declines in future sales, with firms tied to housing or consumer spending bracing for the biggest impact.

The savings among high-income households is large enough—the equivalent of 4.5 years of pre-pandemic spending on food and restaurants—that consumer spending could prove more resilient than expected. But another surge in spending on discretionary purchases would also probably lead to higher inflation and interest rates—and potentially to a larger recession down the road. For lower income Canadians, much smaller cash savings buffers could mean a much more challenging year ahead.

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group”. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic trends and is responsible for projecting key indicators on GDP, labour markets as well as inflation for both Canada and the US.

Proof Point is edited by Edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More