Key findings:

- The U.S. is moving to reengineer critical supply chains and reshore manufacturing to address national security, resiliency, pandemic recovery and climate change challenges.

- A new continental trade strategy could help reestablish Canada’s export sector as a key driver of economic growth, pushing toward an ambitious but reasonable target of $1 trillion* in additional exports by 2030.

- The Biden administration’s climate priorities could spark investments in carbon capture technologies, with CCUS markets potentially worth $12 billion per year in Canada and $90 billion in the U.S.

- America’s focus on electric vehicles, batteries and clean energy could benefit Canadian firms as they aim to supply growing domestic demand.

- To win critical mandates and investments in advanced manufacturing, Canada will need to address long-running competitiveness issues and declining U.S. market share.

- Trade shifts stand to disrupt industries at the core of Canada’s export strength: autos, energy and metals and minerals that accounted for more than half of exports to the U.S. or $227 billion in 2019.

- Canada’s advantages include expertise in clean technology, a free trade pact with the U.S. and Mexico, and large deposits of natural resources critical to electronic devices.

- New investments in skills training and strategic immigration will be essential to Canada’s ability to retain or win higher-value aspects of supply chains.

- A sense of urgency is needed. Tens of thousands of Canadian auto-sector jobs could be at risk without a pivot to EV components, as other countries vie for a role in these supply chains.

* All amounts in Canadian dollars unless otherwise indicated.

The case for rebuilding Canada’s export muscle

THE PROBLEM

THE PAYOFF

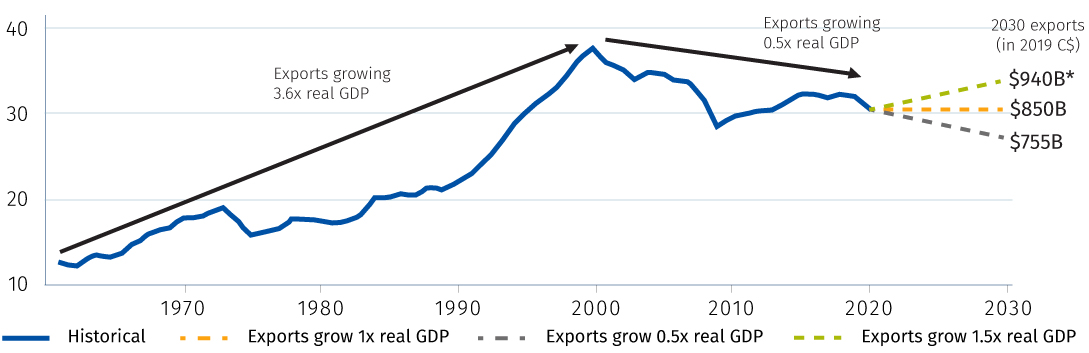

Three scenarios for Canada’s export future

Goods and services export volumes as a share of real GDP

Source: RBC Economics |*Closing the gap between the lowest and highest growth scenarios could boost Canadian exports by a cumulative $1 trillion by 2030.

Why it matters

Shifting U.S. priorities offer Canada a chance to regain lost ground

A new era in Canadian trade is beginning, and it’s not just about dairy or lumber or steel tariffs. It’s about climate change, labour rights and who will control the technologies of the future.

Canada’s largest trading partner, the U.S., is prying open the supply chains at the heart of global trade, aiming to reengineer them to serve new priorities related to national security, the environment and workers. For the Biden administration, these new supply networks will form the backbone of an industrial strategy designed to “reshore” or return production to U.S. soil, reverse decades of job losses, and establish America as a global leader in electric vehicles, batteries, 5G networks and semiconductors.1

For Canada, they represent an opportunity to regain lost ground. Canada’s export competitiveness has flagged in recent years as its share of the U.S. market declined and residential investment and consumer spending drove economic growth. A new continental trade strategy—one built on strategic supply-chain alliances with the U.S.—could help Canada reestablish its export sector as a key driver of growth.

It could also revitalize traditional sectors like autos, energy and metals that have long been the core of Canada’s export strength, accounting for more than half of all shipments to the U.S., or $227 billion in 2019. As these sectors are disrupted by global shifts to greener technologies, a Canadian foothold in new U.S. supply chains could enable them to pivot to higher-growth opportunities.

A continental strategy would give Canada an anchor point in a rapidly changing global trade landscape that will increasingly be influenced by the race for technological dominance between the U.S. and China. President Joe Biden has pledged to “win the competition for the future against China” by strengthening American innovation and building a critical mass of allies to counter its economic power. His “Build Back Better” plan commits trillions to updating U.S. infrastructure like highways, bridges, water and sewer lines, and to nurturing strategic industries through government procurement, tax incentives and subsidies.2

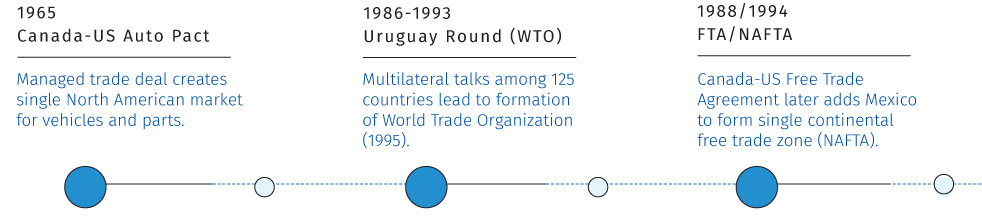

Trading posts: Milestones in Canadian trade

Meantime, Beijing is already moving into the latter half of its “Made in China 2025” model, in which self-sufficiency in critical technologies is also a central objective.

As this contest intensifies, economies around the world are developing their own recovery strategies. The coronavirus upended the mechanics of global trade, turning Chinese factories that had operated reliably for years, making products efficiently and cheaply, into dangerous vulnerabilities. As these facilities shut down, weaknesses in supply chains for critical goods were thrown into stark relief. The resulting shortages of PPE, vaccines and other goods sharpened policymakers’ intentions to build secure sources of supply. They quickened transitions to more regional trading blocs and greener technologies—and created new opportunities for growth. A renewed focus on climate issues, for instance, could spark major investments in emerging technologies like carbon capture, with markets for this technology potentially growing to $12 billion per year in Canada and $90 billion in the U.S., according to our estimates.

Canada enters this new trade landscape with significant advantages. It has expertise in clean technologies, is deeply integrated in North American military and auto supply chains, has a free trade pact with the U.S. and Mexico, and deposits of every critical mineral used in the production of EV batteries. It is a leader in AI innovation—critical to the future of autonomous and electric vehicles—producing the most patents per million people among G7 nations and China.3 And more than at any other time in recent years, Canada and the U.S.’s goals are aligned, as both seek to decarbonize their economies and achieve net zero emissions by 2050.

Success won’t be automatic. Canada will need to manage its trade relationship with China even as it seeks a role in a U.S. strategy designed to curtail Beijing’s economic power. As other countries compete for a role in the supply chains supporting the world’s richest economy, Canada will need to demonstrate how a cooperative approach can advance the objectives of both countries. With Biden considering sizable incentives to attract investment stateside, governments here will have to weigh similar regulatory changes and moves to draw investment north. Canada needs to act quickly to win a stake in the supply chains that will underpin the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Supply chains in successive industrial revolutions

Supply chains have been essential to Western economies since the first and second industrial revolutions demanded parts for steam engines and farming combines. The Third Industrial Revolution—built on software—allowed for massive distribution supply chains, enabling companies to drive broad efficiencies. For Canada, the 1965 Auto Pact extended that distribution, with suppliers locating along major highways and rail lines around the Great Lakes, later connected by software-inspired “just-in-time” manufacturing. Much of that production also moved to Mexico and Asia, as advanced technology met cheap labour. The Fourth Industrial Revolution may enable reshoring, with higher-skilled labour and robots combining to make the next generation of advanced products, from electric buses to medical devices.

State of play

Seismic shifts in trade dynamics for the U.S., China, Canada

![]() The US: Biden pushes to “Build Back Better”

The US: Biden pushes to “Build Back Better”

Pandemic bottlenecks heightened fears about America’s fading technological dominance and over-reliance on foreign firms for critical goods. Most recently, a chip shortage forced several U.S. automakers to halt production while Washington appealed to Taiwan (the world’s biggest manufacturer) for help.4

Shoring up domestic production and reducing U.S. reliance on foreign suppliers (particularly China), are goals Donald Trump shared with the Biden administration—though Trump’s strategies for pursuing them were markedly different. Trump hoped punitive tariffs would force a repatriation of supply chains, more Chinese purchases of American goods (electrical machinery, aircraft and vehicles topped the list of Chinese purchases in 2019) and the narrowing of a trade deficit that rose from US$81.5 billion in 2000 to US$308 billion in 2019.

Results were mixed. The U.S. modestly reduced its trade deficit with China in 2019 but only by shifting to other sources of imports—and its overall trade deficit didn’t improve in Trump’s four years in office. There’s also little evidence that the tariffs spurred manufacturers to move production home, as they remained drawn to the strong capabilities of China’s factories and its growing consumer market. U.S. direct investment into China actually increased by 20% to US$7.5 billion in 2019, led by investments in the manufacturing, wholesale and finance categories. A Phase 1 trade deal exchanged some tariff relief for China’s promise to boost imports from the U.S. (it’s falling well short of target) and commitments to improve intellectual property protection. But it did little to check China’s industrial ambitions. Meantime, American farmers and businesses were subjected to retaliation from China and other nations stung by U.S. tariffs. As agricultural shipments to China plummeted, U.S. farmers drew billions in government assistance.

The Biden administration is taking a different approach. While it’s unclear if it will drop the stick of tariffs, it has signaled plans for plenty of carrots to spur industrial changes—subsidies, Buy America procurement, and tax incentives to encourage the repatriation of production. The “Build Back Better” economic plan envisions spending at least US$4 trillion over 10 years on infrastructure and strategic industries like electric vehicles, batteries, semiconductors and renewable energy.5 The U.S. has also kickstarted a review of critical supply chains with an eye to bolstering their security, possibly through strategic partnerships with allies.

![]() China: A nation of factories to a nation of innovators

China: A nation of factories to a nation of innovators

Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” strategy charts its own equally ambitious economic course, aiming to complete the country’s transition from the “world’s factory” for low-cost goods to a technology-intensive manufacturing powerhouse. The goal isn’t just to occupy higher-value areas of global supply chains. Just as the U.S. is aiming to reduce its dependency on foreign suppliers, China is aiming for self-sufficiency in critical technologies like artificial intelligence, quantum computing, semiconductors, electric vehicles and batteries.

China’s success in nearly stamping out the coronavirus has accelerated its economic ascent. As most other countries battled outbreaks and recessions due to lockdowns, China, the early epicenter of the pandemic, reopened schools, businesses and factories. And its large trade imbalances with other nations grew even larger as it fed steady demand for consumer goods like electronics and fitness equipment in other parts of the world. China’s exports increased 3.6% in 2020.6 Its output is expected to expand 8.2% this year, outpacing other major economies.7

As China’s share of the global economy grows, opportunities for foreign suppliers in its domestic markets are arguably shrinking. Its exports and imports as a share of GDP have declined over the past decade as consumer spending has increased, suggesting China is advancing toward its goal of meeting more of its own needs. And as it competes with the U.S. for technological dominance, China is doing so with a number of key advantages. In 2019, Chinese companies accounted for 80% of the world’s total output of raw materials for advanced batteries.8 Indeed, China controls most of the refining capacity for critical minerals globally despite possessing a significantly smaller proportion of reserves—an advantage it gained through heavy early investments, lower costs and fewer regulatory restrictions. For instance, despite having only 1% of the world’s cobalt reserves, China controls 80% of the global cobalt refining industry, where the raw material is turned into commercial-grade cobalt used in batteries.

![]() Canada: A trading nation loses steam

Canada: A trading nation loses steam

Canada is a trading nation, with exports a critical part of its economic strategy. But trade has not been a significant source of economic growth for many years, as its contributions were gradually overshadowed by consumer spending and residential investment. Over the last 20 years, exports have risen at just half the pace of the overall economy. And despite trade agreements offering some of the best market access in the world, the U.S. remains the destination for three-quarters of Canada’s goods exports—about the same as 30 years ago.

Meantime, Canada’s share of the U.S. market has declined in the face of fierce competition. Between 2000 and 2020, China usurped Canada as the top source of imports to the U.S.—its market share rising to 18.6% as Canada’s fell to 11.6%. Following the global financial crisis, Mexico bumped Canada out of second place, as Canada’s share of North American auto assembly slid to 10% from 17%.

Canada’s underperformance in trade is often tied to geography—it ships more to developed economies with slower growth than to rapidly expanding emerging markets. But higher unit labour costs due to slow productivity growth, a stronger currency and regulatory issues have played a part too.

Canada isn’t a major advanced technology supplier to the U.S. Its exports remain dominated by natural resources, transportation equipment and energy—with mineral fuels accounting for 29% of all exports, followed by motor vehicles at 17%. But its advanced products play a significant role in some arenas, particularly information and communication, electronics, life sciences and aerospace, where shipments of commercial passenger planes, turbojet and other aircraft engines and parts top the list. Canadian exports of knowledge-intensive services including research and development, computer and information services, and IP grew by nearly 12% annually over the past three years, rising to $27.5 billion in 2019.

Opportunities in these and other higher-end exports could expand further as supply chains regionalize, more services and information move to virtual platforms—and concerns about supply-chain resilience and cybersecurity drive demand for local suppliers. For instance, the pandemic has driven major shifts in how healthcare is delivered, amplifying demand for technology that enables virtual healthcare. As Canada’s population ages, emerging technologies will also play a growing role in homecare services, delaying hospital and long-term care admissions.

The trouble with reshoring

Pandemic-related trade disruptions have added to longstanding concerns about lost industrial capacity and over-reliance on imports from China, which have grown nearly eight times as fast as domestic manufacturing sales since the early 2000s.

But reshoring isn’t always the answer.

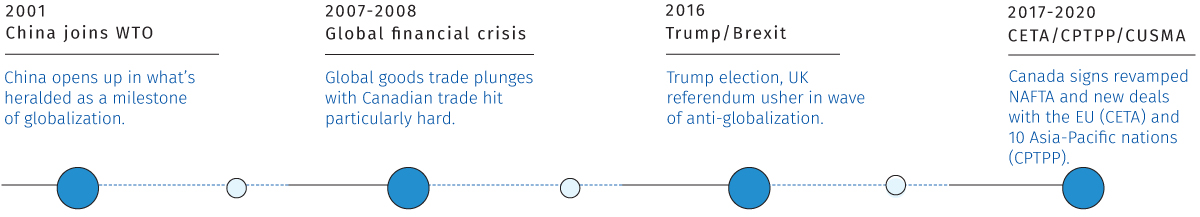

Since joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, China has become integral to Canadian and global supply chains. What’s more, the volume and sophistication of what Canada imports from China’s factories has increased more dramatically than many realize.

In the past 25 years, Canada and China have effectively switched places in the complexity of what they produce, with China’s global ranking in the complexity of its exports rising to 18th in 2018 from 46th in 1995. Canada’s position slipped to 39th from 22nd over the same period—putting it behind both China and Mexico.9 Once valued primarily as low-cost production locales, these countries have increased the sophistication of what they produce while keeping labour costs lower—stifling potential for production in higher-cost countries like Canada. Meantime, Canada’s increasing reliance on commodity exports, particularly crude oil, has pushed it down the complexity rankings.

China complex: Canada is importing more sophisticated goods from China

Imports (in billions of Canadian dollars by complexity)

Source: RBC Economics, Haver Analytics

Today, China supplies more than a quarter of Canada’s small appliances, toys and games, and some clothing and textile products. Canada is heavily reliant on Chinese imports of advanced manufactured goods like cellphones and laptops—items for which Canada has little domestic production capacity. Among the nearly 10,000 unique items Canada imports, China is the largest supplier of 1,845 products and the dominant supplier (accounting for more than 90% of imports) of 120 products. In general, China has a larger market share in products that Canada produces less of, making reshoring difficult.

If there are opportunities to reshore, they tend to be for less-complex products further down the value chain and for which China is a less-dominant supplier–things like office furniture and wood products. But that type of manufacturing is unlikely to generate the sort of high-wage employment or economic opportunities Canada seeks.

Canada’s options

From batteries to ocean tech: Canada may need to consider bolder industrial strategies

Global economies, including the U.S., are confronting the challenges of the post-pandemic era by reviving an old tool: the industrial policy.

Canada will be pressured to do the same as it competes for a stake in the supply chains that will drive North America’s economic future. The industrial strategies taking shape globally are about more than just the location of factories. They’re about recapturing lost production capabilities, safeguarding national security, protecting the environment and rebuilding geopolitical and economic strength. They’re about focusing resources and attention on specific economic and social goals.

Ottawa has tiptoed up to this line repeatedly over the decades, most recently unveiling a supercluster strategy that put $1 billion into five specific sectors in hopes of developing high-potential Canadian technologies. But rarely have the federal and provincial governments, in concert with business, labour and civil society, united behind a single concerted effort.

Industrial policy is broadly defined by the Roosevelt Institute as “any government policy that encourages resources to shift from one industry or sector into another, by changing input costs, output prices, or other regulatory treatment.”

Critics argue that task is best left to the free market—that government intervention may not be the optimal approach economically. But with so many countries marching in this direction, it may be the “optimal second best” choice for Canada.

The U.S. has successfully used industrial policy to advance national security and economic goals in the past, deploying massive government funding, resources and regulatory reforms to assist specific sectors. Asian and European countries too, have long histories with the approach, and more are embracing it today as part of their pandemic recovery funding. Ambitious digital growth and decarbonization strategies are now common, with numerous sector, technology or business-specific supports. With these tools, global recovery dollars are being used directly or indirectly to establish national footholds in growing supply chains.

For Canada, any such plan will necessitate a comprehensive review to make sure the right mix of trade, tax, regulatory and skills policies are in place to capture more than a fair share of any reengineered manufacturing base. Getting that combination right could help reinvigorate Canadian exports, pushing them toward a trajectory that could result in a cumulative $1 trillion in additional exports by 2030—a reasonable target.

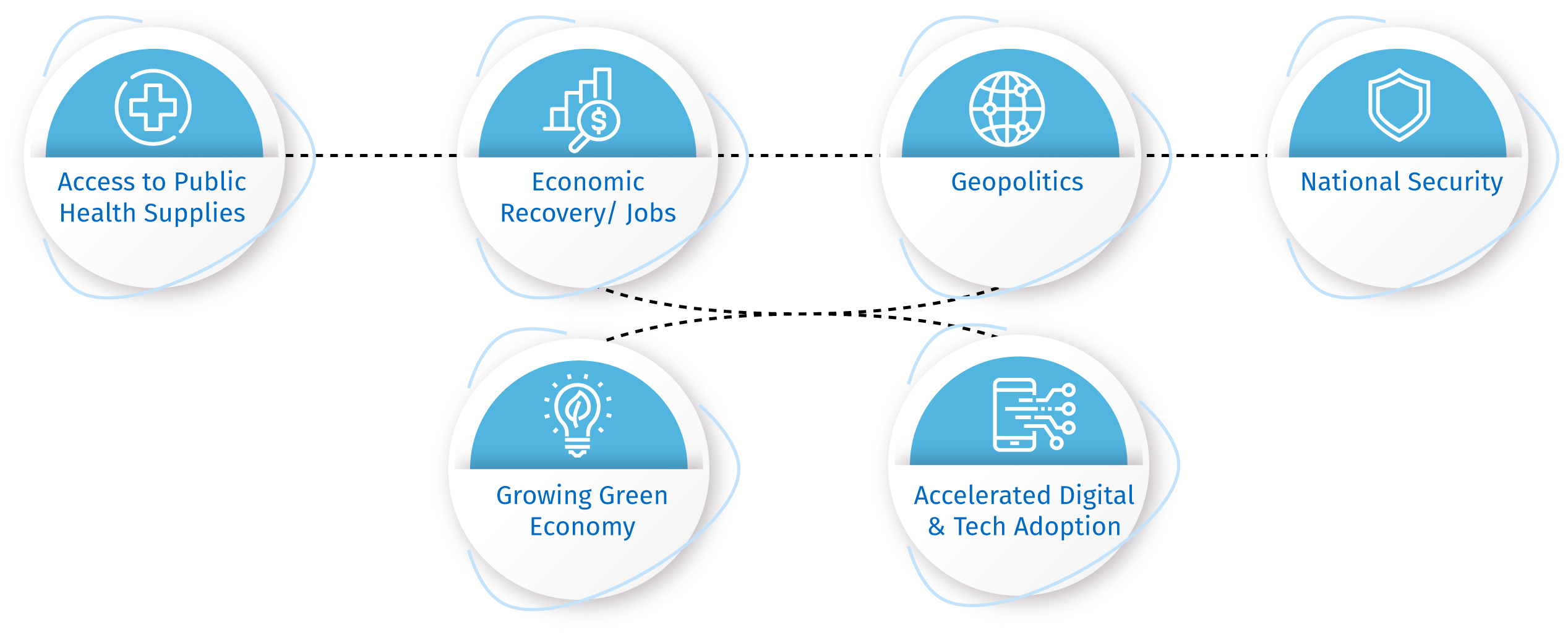

Pressure points: New priorities are shaping global supply chains

Canada’s opportunities: Doubling down on innovation in clean tech

One of the clearest opportunities for Canada lies in the Biden administration’s promise to “make the largest-ever investment in clean energy research and innovation” and to embed clean technologies throughout the American economy. The Biden administration intends to invest US$400 billion over 10 years in this area, use small-scale nuclear reactors to reach a 100% clean energy target and accelerate carbon capture and storage (CCUS) through investments and tax incentives.

US$400 Billion

plans to spend on clean energy

research and innovation.

Clean technologies encompass products and services that reduce greenhouse gas emissions or increase environmental sustainability and protection. Battery electric vehicles are ”clean tech,” but the category is much larger than this, encompassing solar and wind energy, energy-smart thermostats and emissions-reducing crop management techniques.

The potential size of the overall opportunity is just as substantial. Markets for carbon capture and storage could reach $12 billion per year in Canada and $90 billion in the U.S. if industry leans on the technology to cut emissions by 30% from 2018 levels, according to our estimates. Globally, clean tech activity was expected to exceed $2.5 trillion by 2022 based on forecasts in 2017, well before increased global climate commitments were made.11

Canadian companies are well-positioned to take advantage of rising U.S. demand: 12 of the 2020 Global Cleantech 100 companies are Canadian.11 And Canada exported about $10.6 billion of clean tech products in 2019, accounting for a greater share of total exports (1.8%) than natural gas (1.5%).12 In 2017, the U.S. was the destination for 70% of Canadian clean tech exports. So far, Canada has been a leader in early uptake of CCUS, drawing $4 billion in capital investments, capturing 4.2Mt of carbon annually at an estimated cost of $100 to $150 per tonne, or $420 million to $640 million each year.13

70

tech exports shipped to the U.S.

in 2017.

Nevertheless, scaling up technologies has been a challenge, given the size of the Canadian market. Canada ranks fourth in the 2017 Global Cleantech Innovation Index, but lags the leaders in commercialization success.14 With a small domestic market and climate standards not yet stringent enough to encourage broad uptake at home, Canada doesn’t always have the initial buyers to prove the concept.15

Case study: Entering a new lane: Canada can expand into EV and battery manufacturing

The Biden administration aims to spark an EV boom in the U.S., amid a broader global shift to clean transportation. EVs will account for around a third of global vehicle sales by 2030, up from just 4% now, according to RBC Capital Markets. 16 The share is expected to be closer to 25% in the U.S.

Domestic sales are critical to boosting U.S. production, particularly since 80% of EVs are manufactured in the regions where they’re sold. 17 Biden aims to generate that demand through a combination of purchase incentives, fuel-economy standards and 500,000 new public EV charging stations—enough to support 25 million EVs or 9% of the current U.S. vehicle fleet. 18 He also intends to convert 650,000 federal, state, local and tribal fleets to “clean and zero-emission” vehicles, offer grants to retool factories and reinstate federal tax credits for EV purchases. 19

For Canada, securing a role in these emerging supply lines will be critical. As Canada’s share of traditional North American auto assembly has declined, it has also lagged other countries in expanding EV output, contributing just 0.4% of global EV production in 2018 versus 2.2% of all global vehicle production. 20

Despite these challenges, auto and auto-parts production remains one of Canada’s most important manufacturing sectors, accounting for nearly 1% of GDP and employing 135,000 Canadians. Tens of thousands of those jobs will hinge on a transition to domestic EV production.

Amid batteries, power electronics and other battery-EV (BEV) components, only about half of a BEV’s content overlaps with internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs). 21 So while retooling assembly plants will help preserve jobs, Canada will need to expand further into these new areas of the supply chain too. What’s more, labour is distributed differently in BEVs, with more hours concentrated in production of batteries and power electronics. 22 Automakers’ recent commitments to produce EVs in Canada have secured thousands of jobs, but without battery cell and power electronics production in Canada, we think 3,500 auto-sector jobs could be at risk (in addition to larger employment losses on assembly lines.) Another 1,000 jobs could be lost if Canadian automakers and parts suppliers aren’t able to pivot some of their business to other EV-specific content like electric motors.

Canada enjoys a number of powerful advantages as it moves into the EV space. These include:

- Deep integration in North American auto supply chains.

- Reserves or production of every critical mineral and raw material used in production of EV batteries.

- 75% North American content requirement for EV batteries under CUSMA.

- 6th-largest production of nickel globally, generating 10% of the high purity, Class 1 nickel sought by the global battery industry.

- Top 10 producer of cobalt, with active mines in northern Quebec.

- Several projects in development to produce lithium, including Val d’Or and Nemaska in Quebec—the latter aiming to produce enough lithium hydroxide to meet 14% of North American demand by 2030.

- Large deposits of graphite being mined or appraised in Lac-des-Iles, Matawinie, Lac Guéret and other locations in Quebec. 23

But while Canada placed fourth in Bloomberg NEF’s 2020 lithium-ion battery supply chain ranking—largely due to its raw material and clean electricity supply—it has so far been passed over by major battery producers. 24 Meanwhile the U.S., ranked behind Canada by BloombergNEF, has secured major investments in battery production in Georgia and Ohio with help from government subsidies. While Canada’s cheap, clean electricity, skilled labour force, and ethical mining practices are important magnets for investment, so too are these government incentives.

To capture more of the EV supply chain—particularly in batteries—Canada is going to have to weigh the benefits of spending more public dollars to draw production north of the border. At the same time, it must continue to pursue policies increasing EV penetration here. Canadian companies will also need to continue developing the advanced automotive intellectual property and software that are an increasingly valuable part of the next-generation vehicle.

Listen to the latest Disruptors podcast episode, Charging Ahead: Canada’s Role in The E-V Revolution, for a deep dive into the rapidly-evolving world of EVs and the supply chains Canada needs to create to be a player in the growing, global market.

Beyond clean tech: Canada’s edge in agriculture, oceans, software and more

A Canadian industrial policy should be comprehensive and built to maximize all of Canada’s existing strengths, including in the fields of agriculture and food production, aerospace, oceans tech and software.

3.4%

export growth between

2011 and 2019.

In particular, software and services—often overlooked in industrial policy—will fuel industries and trade now and into the future. While global trade in goods has been close to flat since 2011 (increasing by just 0.4% per year), trade in services has posted steady increases, rising 4.1% annually over the same period. In Canada, goods exports grew at a stronger 3.4% pace between 2011 and 2019 but were still outpaced by growing services exports, which increased 6.1% per year over the same period.

6.1%

export growth between

2011 and 2019.

If pandemic disruptions are prompting a shortening of supply chains in the realm of traditional physical goods, the opposite is happening in the arena of digital and services trade. Software companies facing far fewer physical barriers related to shipping are going global overnight, accessing the cloud to sell their products anywhere. More traditional firms are embracing virtual platforms too—in fact, much of the recovery in goods trade during the pandemic can be tied to services as retail transactions and other activities moved online. To be sure, the pandemic has delivered a decisive blow to certain services sectors, including travel and tourism—but for these other sectors, it has provided an opportunity to thrive.

More opportunities will emerge as the “Internet of Things” dissolves the distinction between goods and services. For instance, as the importance of digital services and artificial intelligence in autos, appliances and other goods rises, so too will concerns about cybersecurity and the safety of personal data—leading to more local alliances between manufacturers and software firms. Canada is a hub for the AI that supports many of these IoT technologies. The number of active Canadian firms with a flagship product or service that uses AI has doubled in the past five years to 660. And Canada has produced the most AI patents per million people among G7 nations and China. 25

North America First… not last

The Biden administration’s “Build Back Better” policy may be the latest and most pronounced example, but China, Japan and South Korea have all adhered to industrial strategies for decades. And continental Europe is resurrecting some of its past plans for state-directed industrial policies as it aggressively pursues green transitions.

Canada will need to move quickly to shape its own industrial strategy.

International alliances will be critical. Coordinating with other nations, especially in Europe and the Indo-Pacific region, can ensure a Canadian industrial policy is competitive. For instance, the Quad or Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, a 15-year-old alliance between the U.S., Australia, Japan and India, was recently revived to develop joint strategies to counter China’s ambitions around advanced manufacturing, climate tech and biotech.

Canada has much to contribute to such partnerships. It’s a leader in environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG), has high environmental standards, engagement with Indigenous communities and a leading immigration and post-secondary education system. It’s the only G7 country to have free trade agreements with all other members and enjoys preferential market access to both the European Union and 10 Asia-Pacific nations under the CPTPP.

As new alliances and partnerships are formed, any strategy must be careful not to alienate China, a major buyer of Canadian agriculture and natural resources. Continuing this trading relationship, while simultaneously seeking a significant role in a U.S. agenda designed to curtail Chinese economic power, may be difficult. It may also be outside of Canada’s control: Washington may require close allies take a hard line on China, prompting China in turn to punish U.S. partners. Canada risks being caught in the middle.

To become more competitive, Canada will need to reassess:

Trade policy. Consider modern policy tools to support strategic goods, including EVs and parts, in the face of state-supported competition from other markets. Border carbon adjustments can factor in the cost of carbon in domestic goods versus foreign goods and components.

Investment policy. Establishing priority sectors for public and private investment, and ensuring competiveness without wasting public money by competing with bigger governments. Infrastructure investment will also be key, as more roads, rail and bridges and ports are needed to connect new supply chains.

Procurement policy. The Government of Canada purchases roughly $22 billion in goods and services each year, for defence, health care and other purposes—making it one of the largest public buyers. 26 Municipalities, too, spend billions on vehicles and other expenses, making procurement a powerful tool for making markets and supporting specific sectors.

R&D policy. Research and development more than doubled in China between 2000 and 2018, rising to 2.1% as a share of GDP. R&D funding in the U.S. rose from 2.6% to 2.8% over the same period. By comparison, in Canada this funding slipped from 1.9% to 1.6%. A more robust and targeted Canadian R&D strategy, including greater contributions from the private sector, is needed to fuel domestic innovation and ensure a focus on key sectors.

Skills strategy. Advanced manufacturing depends increasingly on skilled labour, from engineers to designers and coders. Universities and colleges need to become even greater strategic partners in clusters, acting as hubs for innovation as new technologies and supply lines emerge. A skills strategy will be essential to the development of critical minerals for instance, which requires an approach that’s advanced when it comes to research and trade and also inclusive of Indigenous and other communities.

Conclusion

At its core, the Biden administration’s “Build Back Better” plan is about much more than reshoring supply networks. It’s about revitalizing America’s manufacturing might, ensuring economic and job security, protecting the environment and addressing the vulnerabilities exposed by the pandemic. It’s about countering the rise of China by propelling America to the forefront of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Other countries around the world are rebuilding their economies and trade policies around similar objectives—and using industrial policy to power the change.

In this rapidly changing global landscape, Canada finds itself at a pivot point. A comprehensive Canadian strategy, one built to leverage existing strengths, coordinate with the U.S. and international allies and establish new footholds in North American supply chains could usher in a new phase of economic growth. It could reinvigorate Canada’s export sector and help regain lost U.S. market. It could also offer new chances to traditional Canadian industries set to be disrupted by the changes underway.

To consider

- Create a public/private body to urgently build on the findings and recommendations of the Industry Strategy Council’s December 2020 report, 27 with the goal of developing coherent trade, competitiveness, and industrial strategies to position Canada in the green, digitally enabled economy.

- Build a Canada-U.S.-Mexico Council to map out comprehensive strategies for key North American supply chains, including electric vehicles, batteries, semiconductors and telecommunications.

- Establish Canada as the principal, secure supplier of critical minerals to the U.S. This can be achieved by advancing the Canada-U.S. Joint Action Plan on Critical Minerals Collaboration and identifying other cross-border opportunities following an evaluation of reshoring objectives.

- Seek a voice in U.S. discussions on critical minerals supply with Japan, Australia and India through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue. And evaluate the potential of a North American requirement under CUSMA that all raw materials used in the manufacture of batteries, EVs and other vehicles be ethically sourced.

- Advance Canada’s export diversification strategy, opening new global markets for Canadian businesses beyond the U.S.—and in particular with fast-growing emerging markets. Promote greater utilization of Canada’s 14 existing trade pacts with 51 countries, including CETA and the CPTPP. Continue to work with allies on strengthening and modernizing the WTO and other multilateral trade bodies.

1. The Biden Plan to Ensure the Future is “Made in All of America” by All of America’s Workers | Joe Biden for President: Official Campaign Website

2. Joe Biden’s Plan to Rescue U.S. Foreign Policy After Trump | Foreign Affairs

3. GRO_AI_Report_FINAL_2.pdf (d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net)

4. Biden Team Pressing Taiwan, Allies on Auto Chip Shortfall – Bloomberg

5. Biden’s $4 Trillion Industrial Policy Faces Bigger Hurdles Than Politics (msn.com)

6. China trade: export surge continued in December, pushing surplus to record high | South China Morning Post (scmp.com)

7. China Set to Topple U.S. as Biggest Economy Sooner After Virus – Bloomberg

8. China Dominates the Global Lithium Battery Market – IER (instituteforenergyresearch.org)

9. https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/

10. https://www.smartprosperity.ca/sites/default/files/clean_innovation_report.pdf

11. https://www.marsdd.com/news/canadian-companies-global-cleantech-100-2020/

12. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610062901&pickMembers%5B0%5D=1.1&pickMembers%5B1%5D=2.10&cubeTimeFrame.startYear=2015&cubeTimeFrame.endYear=2019&referencePeriods=20150101%2C20190101

13. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/emissions-scenarios/

14. https://www.cleantech.com/2017-global-cleantech-innovation-index-a-look-at-where-entrepreneurial-clean-technology-companies-are-most-likely-to-emerge-from-over-the-next-10-years-and-why/

15. https://www.ic.gc.ca/eic/site/098.nsf/vwapj/ISEDC_CleanTechnologies.pdf/$file/ISEDC_CleanTechnologies.pdf

16. RBC ESG Stratify: Electric Vehicle Forecast to 2050

17. https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/Canada-Power-Play-ZEV-04012020.pdf

18. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-12-02/joe-biden-plan-to-fight-climate-change-could-sell-25-million-electric-cars

19. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/technology/joe-biden-is-throwing-the-weight-of-the-government-behind-electric-vehicles/ar-BB1d6e2Q

20. https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/Canada-Power-Play-ZEV-04012020.pdf

21. https://www.bcg.com/en-ca/publications/2020/transformative-impact-of-electric-vehicles-on-auto-manufacturing

22. https://www.bcg.com/en-ca/publications/2020/transformative-impact-of-electric-vehicles-on-auto-manufacturing

23. https://www.canada.ca/en/natural-resources-canada/news/2020/01/canada-and-us-finalize-joint-action-plan-on-critical-minerals-collaboration.html

24. https://about.bnef.com/blog/china-dominates-the-lithium-ion-battery-supply-chain-but-europe-is-on-the-rise/

25. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/uot/pages/301/attachments/original/1594219597/GRO_AI_Report_FINAL_2.pdf?1594219597

26. The Procurement Process – Buyandsell.gc.ca

27. Restart, recover, and reimagine prosperity for all Canadians – Innovation for a better Canada (ic.gc.ca)

Download the PDF

About the Authors

Josh Nye is a senior economist at RBC. His focus is on macroeconomic outlook and monetary policy in Canada and the United States. His comments on economic data and policy developments provide valuable insights to clients and colleagues, and are often featured in the media.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

Cynthia Leach helps shape the narratives and research agenda around the RBC Economics and Thought Leadership team’s forward-looking economic and policy analysis. She joined the team in 2020. Previously, Cynthia was an executive at Finance Canada, most recently heading a team responsible for housing finance policy covering housing-related risks, mortgage lending and funding markets, and the commercial activities of Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. She also has experience in current economic analysis and fiscal policy.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More