Highlights

- Fed and ECB kept up hawkish rhetoric in December, attempting to guide terminal rate expectations higher

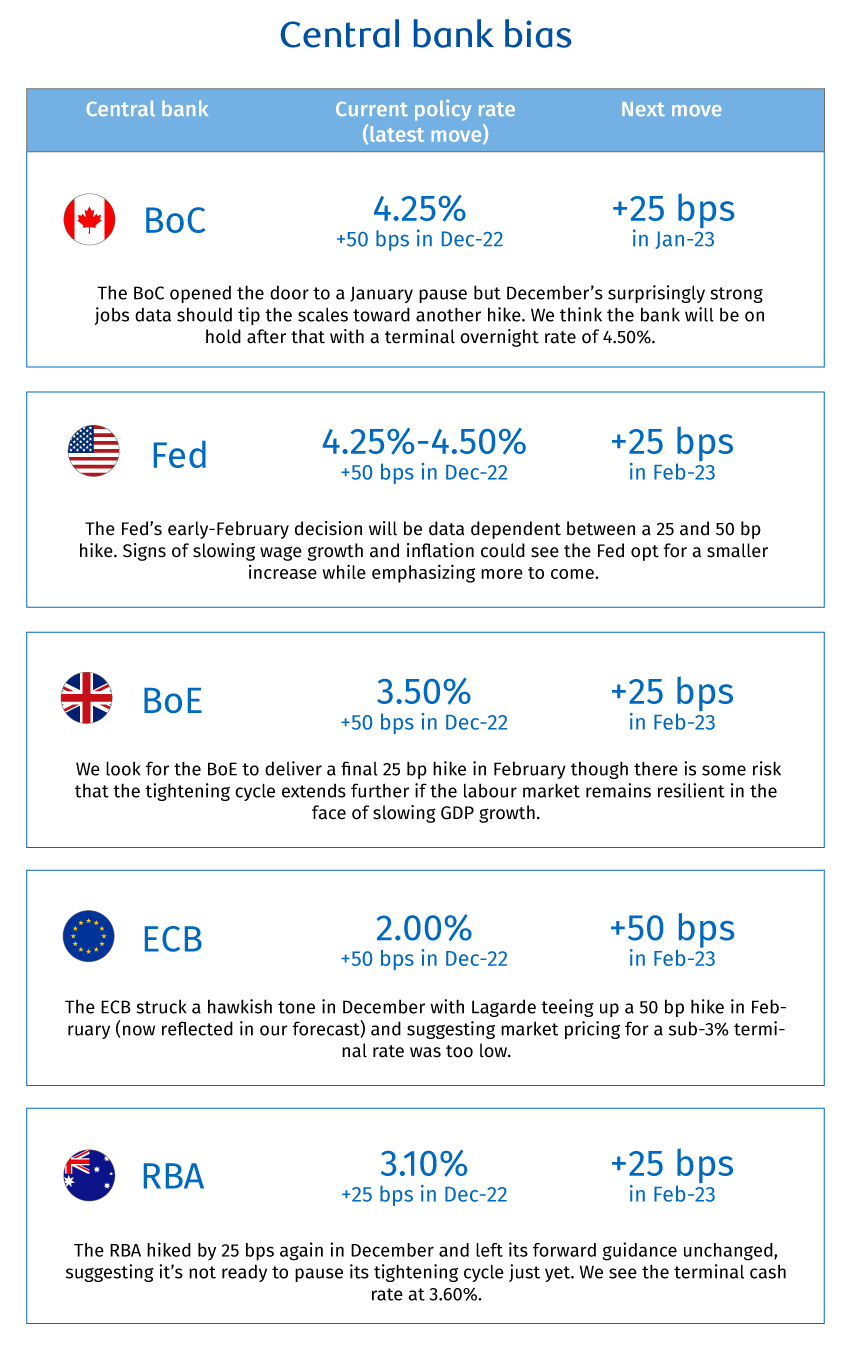

- Strong jobs data will delay the BoC’s pause—we now expect a 25 bp hike in January

- Central banks not done raising rates just yet but 2023 should be a better year for bond markets

- Labour markets holding up but will eventually soften as economies slip into recession

Mid-December meetings by the Fed and ECB proved relatively hawkish with both central banks attempting to guide policy rate expectations higher. The ECB had more success moving the market and we’ve raised our terminal deposit rate forecast by 50 bps to 3%. A surprising (or surprisingly early) decision by the Bank of Japan to raise its cap on 10-year JGB yields put additional pressure on global bond markets which sold off modestly over the holiday period. That capped an ugly year for bonds with US Treasuries returning a 12.5% loss, the worst performance in at least half a century. The yen’s post-BoJ rally kept the US dollar close to a multi-month low but the greenback still gained nearly 8% last year, its strongest increase since 2015. The S&P 500 recorded an 18% loss in 2022 with the index closing out the year near our equity strategist’s year-end target of 3,800.

The bond market is off to a better start this year, in line with our view that last year’s pain won’t extend into 2023. Some of the global factors that pushed inflation higher in 2022 are turning disinflationary, and we don’t see labour markets maintaining their recent resilience in the face of sustained, restrictive monetary policy. Central banks aren’t done raising interest rates just yet—we now see the BoC adding one more 25 bp hike later this month before pausing—but the market is well priced for what tightening remains. We look for government bond yields to grind lower over the course of the year with some modest curve steepening as central banks move to the sidelines and the market begins to contemplate rate cuts. Easing inflation and lower yields should support equities over the course of the year (our strategist’s year-end S&P 500 target is 4,100) although we’re likely to see some choppiness in the near-term as economic activity slows.

Easing global inflationary pressures…

Many of the global factors that contributed to a surge in inflation in 2022 have eased significantly. Key commodity prices that skyrocketed following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine are back to pre-invasion levels. Oil prices are more than one-third below last year’s highs as Russian supply has generally held up in the face of tightening sanctions. A record 220 million barrels of oil drawn from the US’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve in 2022 helped dampen the impact of OPEC supply cuts. Even European natural gas prices, where supply from Russia has been curtailed, are now below year-ago levels thanks in part to a mild start to winter. Shipping costs have fallen and supply chain pressures have eased significantly relative to this time last year, with some help from slowing global goods demand. The surge in COVID outbreaks in China could add to near-term supply chain challenges, but the move away from the country’s zero-COVID policy should ultimately allow for further easing in bottlenecks down the road. Geopolitical risks remain elevated and could disrupt some of these trends but at this stage global factors are looking more disinflationary than inflationary.

…leave central banks focused on tight labour markets at home

With less price pressure emanating from abroad, central banks are focusing on domestic sources of inflationary pressure—particularly tight labour market conditions that are driving wages higher. Since the start of the pandemic, unit labour costs in the economies we track have grown at 2-3 times the pre-pandemic annualized run rate. Inflation has largely eroded workers’ purchasing power thus far, but if wage growth remains firm even as other sources of inflation slow, labour costs could prove to be a persistent source of price pressure. Unemployment rates in Canada, the US and UK are at or slightly above cycle (and multi-decade) lows while jobless rates in the euro area and Australia have continued to fall. Ratios of job openings to unemployment remain well above pre-pandemic levels but have started to turn lower—a tentative sign that supply-demand imbalances in the labour market are beginning to ease.

Central banks will want to see more evidence of labour market cooling to be confident that inflation will move back to target on a sustained basis. Indeed, tight job markets and strong wage growth were central to the ECB and Fed’s more hawkish rhetoric in December. But the labour market is a lagging indicator—it takes time for businesses to evaluate whether a slowdown in new orders/sales is a blip or trend, and to adjust their workforces accordingly—and monetary policy itself acts with lags. If central banks continue to hike until there is clear evidence that unemployment is trending higher, they risk over-tightening. At some point policymakers will have to judge whether monetary policy is restrictive enough to return unemployment and wage growth to more sustainable levels over time. The BoC looks closer to doing that than other central banks, but perhaps not as soon as January. We think other central banks will get there eventually, ultimately delivering less tightening than their guidance or market pricing suggests.

Jobs data could push BoC toward another hike

Recent BoC meetings have been close calls and that will continue to be the case in early-2023. In December, Governing Council said it is “moving from how much to raise interest rates to whether to raise interest rates” and future decisions will be “more data dependent.” Indicators since then haven’t been unanimously strong—the latest GDP and CPI reports were fairly ‘status quo’—but impressive jobs numbers should tip the scales toward a hike rather than a hold. While we await key CPI and survey data ahead of the BoC’s next meeting, we’re now penciling in a 25 bp hike later this month, lifting the overnight rate to 4.50% to match the pre-GFC peak.

That impressive jobs data saw Canada’s economy add more than 100,000 jobs for the second time in three months in December. The unemployment rate dipped to 5.0%, only slightly above record lows seen over the summer. Canada’s jobs numbers are volatile but the trend has been one of resilience with 29,000 jobs added over the second half of 2022, down only modestly from the 37,000 pace seen in the first half of the year. The unemployment rate has moved sideways at a very low level and wage growth has consistently been above 5%, showing few signs of further acceleration but also little evidence of slowing. Again, these data should be seen as a lagging indicator, and much of the impact of last year’s rate hikes is still to be felt. But for a central bank emphasizing data dependence, it will be hard to pass up another hike.

Other recent data shouldn’t do much to change the BoC’s outlook. GDP figures continued to show Canada’s economy gradually losing momentum over the second half of 2022, although upward revisions to prior months have us tracking a stronger Q4 gain than we (and the BoC) previously thought. For CPI, the headline reading fell by slightly less than expected and year-over-year rates for both headline and core inflation have failed to slow meaningfully in recent months. We continued to see signs of inflationary pressure becoming less broadly based, and core price growth has slowed on a month-over-month basis but progress has been sluggish (3-month annualized readings still above the BoC’s 1-3% target band). Upcoming BoC surveys will give policymakers a better idea of whether early signs of slowing inflation are feeding into inflation expectations.

Fed slows hikes but maintains hawkish tone

The Fed delivered a widely-expected 50 bp hike in mid-December, dialing back the pace of tightening following four consecutive 75 bp increases. But it maintained the hawkish tone that has been in place since mid-2022, once again trying to guide market expectations for the peak policy rate higher. It left its forward guidance unchanged—“ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate in order to attain a stance of monetary policy that is sufficiently restrictive”—despite some expectation that it would soften its tightening bias. The vast majority of committee members now see fed funds rising above 5% in 2023 with the dot plot median revised up by 50 bps relative to September. The committee doesn’t expect to begin lowering rates until 2024 whereas we (and the market) see cuts in the second half of this year.

We think the Fed’s hawkish rhetoric continues to be motivated by a desire to keep financial conditions from prematurely easing. Indeed, minutes from the December meeting showed concern that “an unwarranted easing in financial conditions, especially if driven by a misperception by the public of the Committee’s reaction function, would complicate the Committee’s effort to restore price stability.” The market largely looked through the Fed’s hawkish dot plot, interpreting it more as an effort to massage expectations than actual policy intentions. Treasury yields were little changed following the announcement and market pricing for the terminal fed funds rate remains below 5%.

While December’s payroll report was stronger than expected (223,000 jobs added and the unemployment rate returning to a cycle low of 3.5%), markets seized on slowing wage growth and Treasuries rallied. (A disappointing ISM non-manufacturing survey released shortly after contributed to the market reaction.) The Fed might not view the latest jobs numbers quite as dovishly—ultra-low unemployment will make it difficult for wage growth to slow significantly further, and the current pace is still well above what would be consistent with 2% inflation. That said, the Fed has put more emphasis on how high rates have to go rather than the pace of hikes. Slowing inflation and wage growth could tilt the committee toward a 25 bp hike in February while reiterating that rates will have to continue to move higher. Beyond that, we maintain our call that the Fed won’t raise rates as much as its dot plot suggests, and that rate cuts will begin sooner than the committee is letting on.

Hawkish ECB points to higher terminal rate

The ECB delivered a widely-expected 50 bp hike at its final meeting of 2022 but struck a surprisingly hawkish tone in its policy statement and press conference. Following a substantial upward revision to staff inflation projections, the ECB sharpened its guidance to suggest interest rates “still have to rise significantly at a steady pace” to ensure monetary policy is restrictive enough to rein in inflation. Its previous guidance simply indicated it “expects to raise interest rates further.” ECB President Lagarde teed up a 50 bp increase at the next meeting in February and said a similar increase is possible in March. She also made clear that the market-implied policy path at the time (with a terminal rate below 3%) was too low. Given the central bank’s hawkish tone we now expect a 50 bp hike in February followed by 25 bp increases at each of its following two meetings for a terminal policy rate of 3% (50 bps higher than our previous forecast). The market is now pricing a terminal rate between 3.25-3.50% following Lagarde’s jawboning. The ECB also announced it will begin QT in March with bond holdings rolling off its balance sheet at an average pace of €15 billion per month until the middle of the year when that pace will be re-evaluated.

Strong wage growth could test the BoE’s patience

As expected, the BoE reverted to a 50 bp hike in December following November’s one-off 75 bp increase. Unlike the Fed and ECB, the BoE didn’t come across as particularly hawkish, simply maintaining its forward guidance that further rate hikes “may be required.” There was a dovish tilt to the MPC’s voting with two members preferring not to raise rates while only one dissented in favour of a larger hike (a second previously-hawkish dissenter voted in line with the majority). Those voting for a 50 bp increase noted that while economic activity is clearly weakening, there were signs of greater-than-expected resilience that made it unclear how quickly the labour market will loosen. Indeed, while the UK economy essentially flat-lined for much of 2022, the unemployment rate has ticked up only modestly. The latest PMI data suggest a softer employment backdrop going forward, though the BoE might have limited patience with private sector wage growth running close to 7% year-over-year. Our forecast continues to assume one more 25 bp hike in February leaving terminal Bank Rate at 3.75%, though risks are tilted to the upside if the BoE doesn’t see sufficient evidence that tight labour market conditions are easing in early-2023.

See forecast tables:

Canada, US And Financial Markets

Josh Nye is a senior economist at RBC. His focus is on macroeconomic outlook and monetary policy in Canada and the United States. His comments on economic data and policy developments provide valuable insights to clients and colleagues, and are often featured in the media.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More