Too many Canadians are struggling to find a home they can afford—making housing a defining issue of this country’s politics and economics.

The crisis now affects middle-income Canadians and extends beyond major cities. It strikes at the core of the Canadian dream of owning a home and is creating intense inter-generational tensions.

This predicament will reach even more alarming levels if not enough is done now.

More than half—one million—of 1.9 million new households by 2030 will not be able to buy a home, according to our estimates. That’s equivalent to almost all the households in Atlantic Canada right now.

Housing affordability is cutting through to government policies on immigration and education and impacting Canada’s reputation and ability to attract talent and investment.

The Federal government’s caps on international students and temporary foreign workers are just some of the recent policy measures announced to address the crisis but it will not shrink housing demand.

Signs that the housing market is heating up again in anticipation of interest rate cuts by the Bank of Canada only highlight why faster action is necessary. How can housing become more affordable if prices keep rising?

It’s not an easy fix. At its core, the housing crisis arose from an imbalance between supply and demand.

Canada’s housing stock hasn’t responded quickly and forcefully enough to soaring demand. Many other factors that contributed to this imbalance are complex ranging from the structural to cyclical, regulations to preferences, and policy to emotions.

The solutions will be many and complex as well. Ultimately, they will need to close the supply-demand gap and tilt the market equation toward an abundance of supply—to bring meaningful home price and rent relief.

However, a main challenge for all stakeholders is how to considerably boost supply at a time when construction capacity is limited and building costs are high. It’s also imperative to think about the type of housing that is needed and the way we build as Canada looks to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

This report will look at the five phases that led to Canada’s housing crisis, how the challenges are being addressed, and what are the best solutions going forward.

Seven ideas to take on the supply and affordability challenge:

Solving the housing crisis will require greater collaboration between governments, industry and other stakeholders because none of them can do it alone. Efforts will have to go beyond what’s been done so far to achieve meaningful and sustained progress toward rebalancing supply and demand.

Homeownership and rent costs hit records

Canada’s housing market took a troubling turn for the worse during the pandemic. The cost of home ownership skyrocketed from mid-2020 across Canada. RBC’s housing affordability measure reached its worst-ever level last year. It’s no longer a story of high prices in Vancouver and Toronto. Ownership costs in roughly two-thirds of urban markets we track now exceed 35% of the median household income—indicating an excessive level.

The share of Canadians who can afford to buy a home has shrunk markedly. We estimate only 45% of all households would have the income to own a condo and a smaller 26% have enough for a single-detached home at today’s prices and interest rates. That’s down from 61% and 49% two decades ago, respectively.

It’s become even tougher for renters and never been more difficult to find an apartment. The rental vacancy rate dropped to 1.5% nationwide in 2023—a historical low. Every single urban market but one (Belleville) has a vacancy rate below what’s considered balanced (3%). And rent has gone through the roof. Canadian renters paid $100 more on average a month last year—that includes tenants living in rent-controlled apartments—or nearly four times the average annual increase in the decade preceding the pandemic.

If affordability remains close to where it is today, many renters won’t be able to afford rent in the future. More than 40% of the one million new households that can’t buy a home by 2030 will also not earn enough to afford rent at the market price.

What led to the housing crisis

A mix of historic policy responses, structural shifts, inflation flare-ups and irrational buying and selling butted against supply constraints, which took housing demand, prices and rent to unprecedented levels. Elements developed in a specific sequence that made the perfect storm in the housing market extremely powerful. Here’s how we got here in five phases. ![]()

Canada’s housing system generally worked well in the past, but the number of people struggling to enter the market grew in the decade before the pandemic, especially in Toronto and Vancouver.

The situation boiled over in the second half of the 2010s. The Bank of Canada’s 2015 rate cuts—to the second-lowest level (0.5%) in the modern era at the time—and the federal government’s pursuit of an expansive immigration policy magnified structural forces boosting housing demand. Millennials in their prime homebuying age and a secular decline in the size of households (in part due to an aging population) had set a strong undercurrent for some time. Vancouver and Toronto overheated mid-decade, causing prices to spiral upward and spark speculative activity (some of which was generated by non-residents).

The heat spread to other parts of British Columbia and Ontario, in part through relocation of people searching for more affordable digs. The number of Vancouver and Toronto residents moving to smaller cities in the same province roughly doubled between 2015 and 2019. This migration and broader factors stimulating housing demand led to serious market imbalances because slow-moving housing supply ultimately undermined middle-income households’ access to homes they could afford.

Meanwhile, a lack of affordable and stable rental options worsened the plight of lower-income Canadians. The stock of purpose-built rental apartments has been largely stagnant since the 1970s and 80s with costs and profitability issues stunting new construction. Condo investors have been the main providers of new rental supply—adding more than 200,000 new rental units to Canada’s four largest cities in the past 15 years. But these generally represented more expensive and less stable options. The gap between supply and demand for affordable rental housing widened over the second half of the 2010s, especially in overheated markets.

Governments’ pre-pandemic housing plans fell short in cooling the market because they mainly relied on demand-side measures.

Since the 1970s and 80s, policymakers’ approach to improving Canadians’ housing situation largely focused on easing access to the housing ladder through tax incentives, mortgage insurance guarantees, special savings plans and other home ownership-facilitating programs. They contributed to Canada’s high homeownership rate.

However, overheating markets and spiraling prices in B.C. and Ontario in the second half of the 2010s prompted new policy action to cool activity and reduce financial system vulnerabilities. In 2016, the B.C. government introduced a 15% property transfer tax on foreign buyers of a home in Metro Vancouver. The city of Vancouver followed with a vacant property tax in 2017. That year, Ontario introduced the Fair Housing Plan, which included a 15% property transfer tax on foreign buyers in the Greater Golden Horseshoe region. And in 2018, the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) expanded the mortgage stress test to uninsured mortgages. All were essentially demand-side measures, and any cooling effect was short-lived. They didn’t address the fundamental imbalance between supply and demand with growth in housing stock falling well short of the number of households being formed. Home prices in B.C. and Ontario fully reversed their initial drop less than a year after new policy measures took effect.

The federal government’s National Housing Strategy launched in 2017, however, focused on supply. It laid out an ambitious plan to support the creation of 160,000 new affordable housing units and repair 300,000 existing units by 2027-2028. A year later, a new government in B.C. rolled out a comprehensive 30-Point Plan to tackle affordability issues that included investments to build 114,000 new affordable homes over 10 years as well as 14,000 rental units.

Then in 2019, the Ontario government also shifted its focus to supply when it introduced More Home, More Choices: Housing Supply Action Plan. It outlined a vision for increasing homebuilding in the province with an emphasis on cutting red tape and shortening the project approval process, increasing density around public transit, making more provincial land available for housing, and lowering homebuilding costs.

But, these plans and strategies were still in their early implementation stages when the pandemic hit.

Lockdown measures at the onset of the pandemic got Canadians reconsidering their housing needs.

Many looked for change in their search of larger living spaces where they could comfortably work and study. The ability to work from home fundamentally altered the relationship between the home and office for many Canadians. It opened new options for where to live and generally stimulated homebuyer demand, especially in areas away from urban cores.

Governments provided massive financial support to households to the tune of hundreds of billions to cope with the economic shock. This aid, in fact, more than offset the loss of income resulting from layoffs. Household disposable income jumped 8.4% in 2020 despite the unemployment rate soaring to a modern-day record (14.1%) that spring. With many spending avenues blocked by lockdowns, the income gain gave a growing number of homebuyers tremendous firepower—to deploy immediately or later.

The Bank of Canada amplified that firepower by pursuing its most aggressive monetary policy easing ever. It slashed the policy rate to as low as 0.25% and launched a quantitative easing program—something it had never done before. These measures flooded the financial system with liquidity, along with other emergency programs the central bank put in place. Canada’s money supply surged between 20% and 30% (depending on the definition used) during the first year of the pandemic.

The drop in mortgage rates alone boosted an average Canadian household’s home purchasing budget by up to 25% (or $133,000) by early 2021, according to our estimates. The boost was more than 35% (or $175,000) if the sizable rise in household income is included. Put another way, the mortgage rate decline and increase in income significantly improved home affordability in Canada. The portion of income an average household needed to cover homeownership costs (RBC’s affordability measure) fell to a four-year low by mid-2020. This combination of factors electrified housing demand across the country.

Competition for available supply heated up very quickly with buyers entering the market in droves by the middle of 2020.

Bidding wars soon emerged in many markets—including areas unaccustomed to such phenomenon—and prices took off.

The rising market heat attracted more sellers, though not nearly enough to match supercharged demand. Inventories of homes for sale plummeted 33% by spring 2021 to the lowest levels in decades—and that was only the beginning.

Rapidly mounting pressures on the housing stock spilled into the new home market. Pre-construction sales spiked in 2021—soaring 25% in the Greater Toronto Area. But converting those sales into newly built homes ran into long-standing construction challenges. Municipal planners had not prepared for such a sudden need to dramatically expand the housing stock. Lengthy and costly project approval processes, as well as other regulatory issues (including highly restrictive zoning), fast-rising building costs and labour shortages slowed the supply response. New construction did rise, but it fell way short of what was necessary.

Soaring prices created a sense of urgency among buyers. Delaying a purchase meant prices could become out of reach later. A “fear of missing out” set in. Every price increase emboldened buyers to get even more aggressive with offers, which added more fuel to the fire. By spring 2021, home prices had surged more than 20% nationwide, entirely reversing the affordability gain at the start of the pandemic.

Households’ rapidly rising wealth (fueled in large part by skyrocketing property values) further incited the frenzy. Existing homeowners had higher asset values they could leverage (at low interest cost) to invest in real estate for either secondary homes or investment properties or to help the next generation of buyers. The “bank from mom and dad” became a more crucial source of financing for first-time homebuyers, especially in expensive markets.

Canadians not tied to a specific market looked beyond where they lived for housing they could afford. This significantly accelerated interprovincial migration—spreading the heat all over Canada. Interprovincial migration jumped to a three-decade high in 2021, which was surpassed the following year. Migration also spiked within Ontario and other provinces, fueling housing demand in many smaller, less “liquid” markets.

The initial liftoff in housing demand during the pandemic was an entirely domestic affair because Canada closed its borders in March 2020.

The reopening of borders in the middle of 2021, however, brought in more people looking for a place to live.

At first, government logistical issues restricted the flow of newcomers. But it eventually turned into a wave of epic proportions in 2022 once federal agencies were able to clear large backlogs and process a spike in new migrant applications.

This wave was partly a catch-up and a response to the pressing needs of Canadian employers. The strong economic rebound that happened after the lockdowns led to widespread labour shortages, especially in low-wage service industries. Many businesses turned to foreign temporary workers to fill the gaps.

A flood of international students also played a big role in the dramatic increase in non-permanent residents. Tight provincial funding prompted many post-secondary institutions to admit more international students (who pay higher tuition fees) into their programs.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 also materially added to the flow of newcomers. Canada has approved 960,000 temporary emergency visas to Ukrainians with nearly 250,000 already in the country. Together, these factors attracted nearly 500,000 net new non-permanent residents in Canada in 2022, and 805,000 in 2023—eclipsing previous highs.

This massive inflow came on top of solid increases in permanent residents to Canada. The number of new permanent residents more than doubled in 2021 (from an unusually low level in 2020) to 406,000 and rose further to 438,000 in 2022 and 472,000 in 2023. The government drew significantly from individuals already in the country on a temporary basis in 2021, but it has relied more heavily on applicants outside the country since 2022 as international travel normalized.

Much of the housing demand from newcomers was directed at the rental market. The effect of surging international students has been especially noticeable in Ontario and B.C. More broadly, there’s been sharp focus on lagging purpose-built rental construction in most of Canada because of a rapidly tightening rental market.

The sustained market frenzy pushed home prices to skyrocket, extending gains since the start of the pandemic to more than 50% nationwide by the early months of 2022. This seriously strained ownership and rental affordability in much the country.

Taming runaway inflation became the Bank of Canada’s number one priority by early 2022 with the economy running hot.

In March, it launched one of the most aggressive rate hiking campaigns it has ever undertaken.

In the 17 months that followed, the policy rate increased 10 times for a total of 475 basis points. The impact on home resale activity was immediate—plunging 40% in a year. Prices also fell in most markets, but only reversed a fraction of the previous two years’ gains. The drop at the national level (between 9% and 15% depending on the measure) just rolled back the clock to slightly less exorbitant values in late 2021.

Soaring interest rates further crushed homeownership affordability. Mortgage payments on a typical home on the market came to represent the largest share of household income ever, denying even more middle-income Canadians access to the housing ladder. This poured even more fuel on the rental market, and caused vacancy rates to drop lower, heating up rent to deeply uncomfortable levels.

High rates also pose a significant obstacle to building more homes. They undermined the economics of new construction projects—including purpose-built apartment structures—which soaring construction costs had already made challenging. New condo project launches have largely stalled since 2022.

Housing starts in Canada fell in 2022 and 2023 by a cumulative 11% (or 31,000 units).

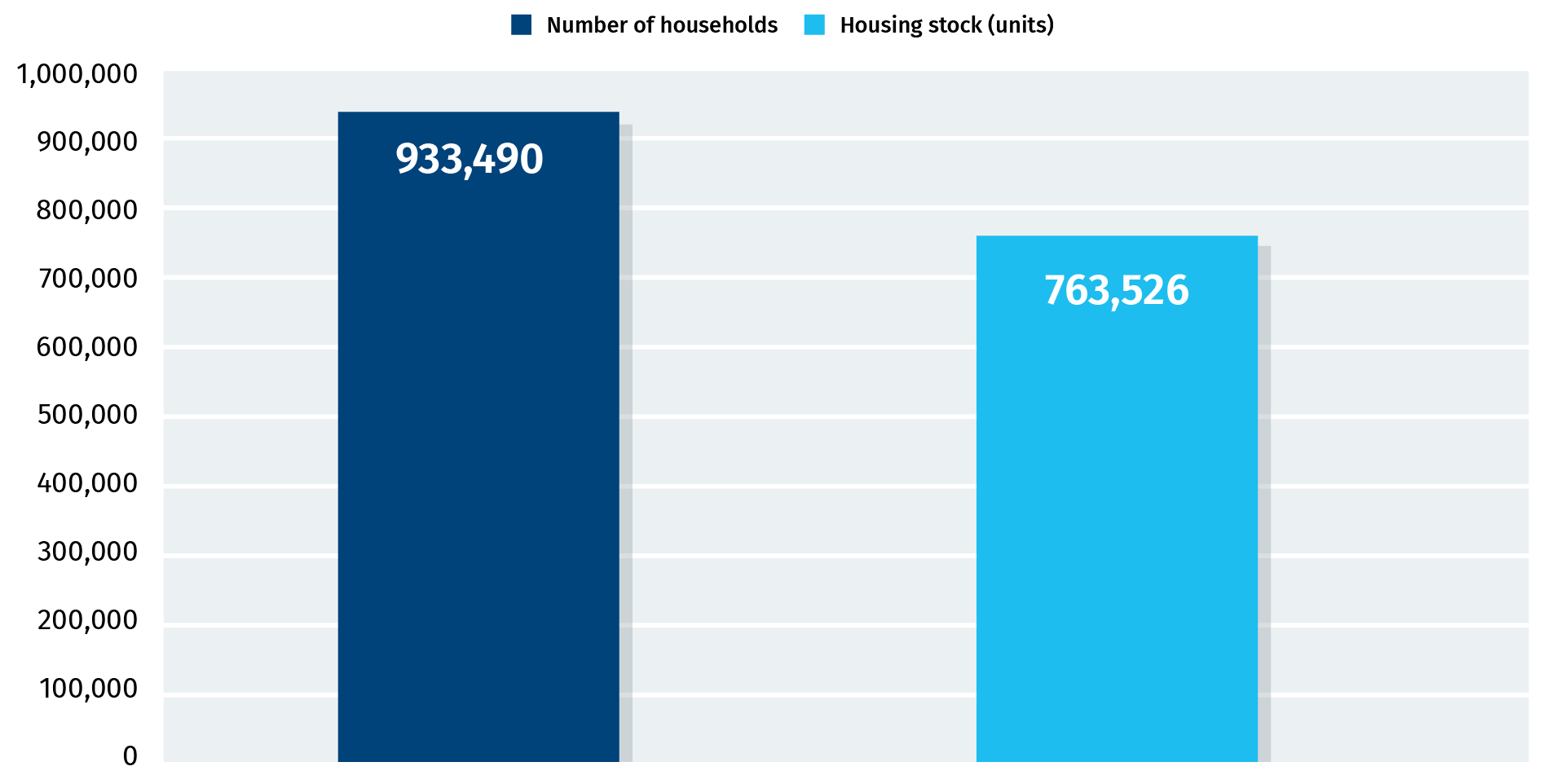

We estimate growth in Canada’s housing stock fell short of new households by 170,000 units during the pandemic (between 2019 and 2023). New households and housing stock have diverged by 545,000 since 2015, given the approximately 375,000 unit shortfall in 2015.

Lower interest rates will help—but just a little

Some relief from high ownership costs is in sight as interest rates start to ease but it won’t be enough to make a meaningful difference.

The encouraging news is the Bank of Canada has likely done enough to win its battle against inflation. We expect it will start cutting its policy rate in the middle of this year, taking it down 100 basis points to 4% by the end of 2024 and an additional 100 points to 3% in 2025. The outlook for long-term rates is more tempered, in part because bond markets have already priced in future central bank cuts. Our rate forecast has five-year Government of Canada bond yields easing a total of about 75 basis points by early 2025. This would pave the way for moderate mortgage rate drops but affordability will still be a significant challenge.

Under our base case scenario, the share of an average household income needed to cover ownership costs would fall to mid-2022 levels by 2025—still extremely taxing. We think access to the housing ladder (albeit improving) will remain limited, which wouldn’t relieve much tension in the rental market.

Stabilizing immigration will take some steam out of demand

The federal government is taking steps to reduce immigration, but the measures will not shrink housing demand.

In November, it announced keeping the permanent immigration target in 2026 unchanged from 500,000 in 2025. This will still be up from the 2024 target level of 485,000. In January, the government further said it would cap the issuance of study permits for international students for two years starting in September 2024. And in March, it indicated it would reduce the proportion of temporary workers in Canada from 6.6% to 5% by 2027—which is a 20% decrease in the non-permanent resident population.

These measures will curb Canada’s record population growth in the years ahead, but average growth between now and 2030 will still be faster than in any of the 25 years before 2018.

Under our base-case projection, population growth would ease from a six-decade high of 3% in 2023 to about 1.3% by 2030. This would add 3.6 million more Canadians by 2030 (from 2023 levels), with much of the increase coming from new permanent residents. We estimate this would lead to the formation of 1.9 million new households over that period or an average of just over 275,000 per year. That’s a more than 15% increase from the 2016-2022 average. Demographic pressures on housing demand may come off the boil, but it won’t entirely subside anytime soon.

Cutting immigration more aggressively would also not instantly restore affordability. It would slow down the growth in housing demand, not shrink it. It would ease upward pressure on home prices and rent only as long as the increase in demand undershoots the expansion of the housing stock—reducing the supply gap.

However, the downside of significantly cutting immigration would be considerable for Canada’s economy over the long run. The population is aging rapidly with at least 500,000 baby boomers reaching retirement age each year until the end of this decade. Our economic growth potential would be hampered if their departure from the labour force isn’t replaced by newcomers.

A tall order for homebuilders

The pace of housing construction would need to jump by nearly half in Canada just to meet future demographic growth.

If building new housing were only relied upon to meet future demand, housing completions would have to rise from an average of 218,000 in the past three years to about 320,000 annually over the 2023-2030 period (accounting for a normal rate of attrition in the existing stock). Higher deliveries would need to happen in the near term given our expectation for peak population growth in 2023-2024.

However, the construction industry has a capacity issue. The level of housing production needed is far above anything ever achieved in Canada. The all-time peak for completions was 257,000 in 1974. The 47% increase needed from recent levels would seriously conflict with production capacity limits. Much of it has to do with labour constraints. Builders already struggle to attract and retain workers. The job vacancy rate in the construction sector (5.1% in Q3 2023) is among the highest across Canadian industries. This could be difficult to resolve over the longer term.

The sector’s aging workforce risks perpetuating the labour shortage. One in five construction workers are at or will reach retirement age within the next 10 years. This represents 330,000 workers to replace if they do retire, making it that much harder to expand the sector’s production capacity.

Meanwhile, housing starts have moderated since rebounding strongly in 2021. Not only have earlier supply chain disruptions during the pandemic led to soaring prices for materials but the spike in inflation, high interest rates and labour shortages have seriously increased project costs and uncertainty in the sector.

Buyers negatively impacted by higher interest rates, a loss of affordability and growing economic uncertainty is why pre-construction home sales (destined for owner-occupants or condo investors) have plummeted in many parts of Canada (including Ontario) since spring 2022.

The construction industry must also build a lot more homes while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Canada’s building stock accounts for 13% of the country’s emissions, making homebuilders key in implementing change to achieve the Net Zero climate target.

![]()

Seven recommendations to take on the supply and affordability challenge

Addressing Canada’s housing needs will largely rest on the ability to significantly expand the stock of housing. Multi-pronged actions will be required to address capacity issues and build homes Canadians can afford. Here are recommendations to scale up housing construction, lower building costs, and ensure we build the right mix of housing while getting the most out of what we already have.

1. Aggressively expand the construction sector’s labour pool.

Canada could need more than 500,000 additional construction workers on average to build all homes needed between now and 2030—and even more than that in the short term to meet peak growth in demand. All avenues should be pursued to get more people working in the sector.

Canada should materially expand the Federal Skilled Trades Program, allocate more points to qualified candidates in the program based on labour market needs, and fast track candidates endorsed by employers. Provinces should do the same in nominee programs. The federal immigration department should maintain a dialogue with the construction industry to ensure immigration programs address structural shortages in skilled trades.

Immigrants working in construction tend to earn above-average wages, establish themselves faster, and rely on social programs less than other immigrants. Recent immigrants are under-represented in the construction labour force. Immigrants with an apprenticeship certificate and non-apprenticeable trades certificate represented just 2.4% of landed immigrants between 2016 and 2021. That’s down from 9.6% during the 1980s. Canada’s immigration programs tend to prioritize university education and language skills to the detriment of occupations that don’t require those like skilled trades. Canada must realign its immigration system by refocusing on the mismatch of skills and long-term labour market needs.

Provinces must reverse the decades-long decline. Promotional campaigns run with the industry should attract a new generation of skilled workers including women, indigenous people, and other under-represented groups. The industry should effectively showcase rewarding careers in skilled trades to high school students and partner with career counselors to identify good candidates.

Employers should consider offering special benefits or work arrangements to slow down the flow of retiring workers.

2. Develop and adopt innovative designs, building techniques and technology.

Continuing to build homes the same way it’s done in the past will make it more difficult to ramp up construction to the level needed and meet GHG emissions targets. New approaches must be pursued to increase the number of homes produced per worker. This won’t be easy. The construction industry has a lackluster track record on productivity. There are more residential construction workers per housing completion today than there were two decades ago. This trend must reverse.

Building entire homes or sections of homes in a factory can significantly increase efficiency, compress timelines, and make costs more predictable. It has several advantages over traditional stick-build construction including lower material waste, and more productive use of labour as workers stay on the factory premises and use state-of-the-art machinery and tools—enabling more efficient workflows. Canada lags in the development of this industry compared to world leaders Sweden (where prefabricated elements are found in 84% of detached homes), Germany (20%) and Japan (15%). Several factors have stifled growth. Carrying large overhead costs in the highly cyclical residential construction industry has deterred companies from making the heavy up-front investment in capital. Manufacturers must put up more of their capital toward the cost of materials and operating expenses compared with traditional homebuilders. Banks can support the industry’s development by recognizing its unique funding needs and mitigating higher risk. The industry also battles with the perception that prefabricated homes are cheaply made. Governments can help grow the industry by requiring prefabricated elements in a certain share of projects they fund—to sustain a minimum volume of business during downcycles. The industry needs to redouble efforts to promote prefabricated housing’s benefits among developers and dispel any stigma.

This could simplify and speed up the process of building a home from approval to completion— taking a page from the post-war strawberry box house program. This approach is especially well suited for basic homes at the more affordable end of the spectrum. It could also help rapidly grow our stock of “green” homes by embedding lower carbon footprint designs. Projects using pre-approved designs should be fast-tracked.

3. Speed up project approvals.

The rules and regulations governing housing development and construction—often well-meaning when introduced—have accumulated greatly over the years. They now represent a complex and cumbersome set of rules that add tremendous time and costs to projects. Project approval timelines in Canada can be among the lengthiest in the world. Streamlining permitting processes, implementing artificial intelligence tools, and speeding up conflict resolution mechanisms would help bring new housing faster to market and reduce development costs and uncertainty. These would make a better investment environment for private or non-profit participants.

Provincial and local governments should remove steps and layers of any process that brings minimal or questionable benefits. This could include reducing the number of studies required and sharpening public consultation and engagement practices to capture the views of the broad community, not just those of a vocal few. Authorities could even exempt small projects (10 units or less) that largely comply with regulations and require only minor variances.

The aim is to tighten maximum timeframes for circulation, review and commentary between regulatory departments and agencies.

The crisis deepens in many Canadian cities with each passing day. It’s imperative that project stakeholders and regulatory authorities fast-track projects that add supply in a shorter timeframe. Projects making use of mass timber or prefabricated elements—known for faster execution speed—could be given preferential treatment.

The federal government’s $4-billion Housing Accelerator Fund and Ontario’s $1.2-billion Building Faster Fund are good examples of how this can be done. These programs offer meaningful financial incentives to municipalities that bring positive changes.

Governments must clear up backlogs and set rules to filter out questionable appeals meant to stall projects and raise costs.

Standardizing building codes across jurisdictions would reduce complexity and risks for developers, and potentially enable homebuilders (including prefabricated home manufacturers) to operate at larger scales.

4. Ease zoning restrictions to make a more productive use of land.

Toronto had 69% of its (net) residential land area restricted to low-density detached and semi-detached homes before recent rule changes by provincial and municipal governments. This represented a very inefficient use of its land base and costly infrastructure. Allowing multiple residential units to stand on single residential lots—as Ontario (and Toronto) and B.C. (and Vancouver) did not long ago—will encourage a more productive use of land over time.

Curbing restrictions that stifled the development of mid-rise and rental housing (known as the “missing middle”) in cities such as Toronto and Vancouver should gradually bring more housing options to neighborhoods including established ones. Removing obstacles to creating new viable housing options (e.g. rentals, townhouses, small condo projects) for currently over-housed Canadians could help free up highly sought units for families. The permitted density must be set higher near transit corridors to better leverage public transit infrastructure and reduce traffic.

There’s potential to expand the residential area of cities by unlocking underused shopping malls and office buildings. Mixed-use communities offer many advantages including proximity to shopping and amenities that reduce driving congestion.

5. Lower the cost of building new housing.

Canada’s challenge is not only to massively expand our housing stock but to do so at prices people can afford. The cost of building new homes has soared and poses serious obstacles to increasing the supply of affordable housing. It’s estimated that materials and labour account for roughly half the costs of new units in most cities. Government charges can represent more than 20% of the cost and the remainder (30% or so) is taken up by land. Efforts should be dedicated to lower or at least contain every cost item.

Mass timber, for example, offers many advantages in construction including lower costs compared to steel and concrete. Another significant advantage is it’s a lower carbon option. Restrictions preventing more widespread use of such materials should be eased. Consideration should be given to permit wood construction for building up to 12 storeys as B.C. has done since 2021.

Development charges from municipalities to cover the cost of additional infrastructure needed by new projects—as well as cash payments to satisfy parkland dedication and other community amenity contributions—must be paid upfront by developers. They are ultimately passed on to end users. Development charges can top $100,000 for a condo apartment in cities within the Greater Toronto Area, while varying considerably across municipalities. It’s a key source of revenue and it may be difficult for municipalities to entirely forgo such charges, but they could modulate them according to home prices to minimize the burden on more affordable housing projects. However, municipalities should consider waiving development charges and parkland cash for in-fill projects that don’t require material additional infrastructure investment.

Many building code requirements add costs, yet the benefits (for safety or otherwise) of some may no longer be significant. Authorities should consider easing some code stipulations to lower project costs. One example is the requirement of having two means of exiting any multi-unit residential building of more than two storeys. A single exit way could safely be allowed for buildings of up to six storeys as common in other countries. Other examples include minimum parking requirements and shadow guidelines, which could be reduced or eliminated entirely.

The cost of land is set by the market. But there are opportunities to build homes on sub-optimally utilized land. For example, shopping mall owners could build residential projects on underused parking lots, which would not necessitate the purchase of land. The same could be done to other real estate properties where development could be done without the acquisition of land. Changes to zoning regulations may be necessary.

6. Change the mix of housing being built.

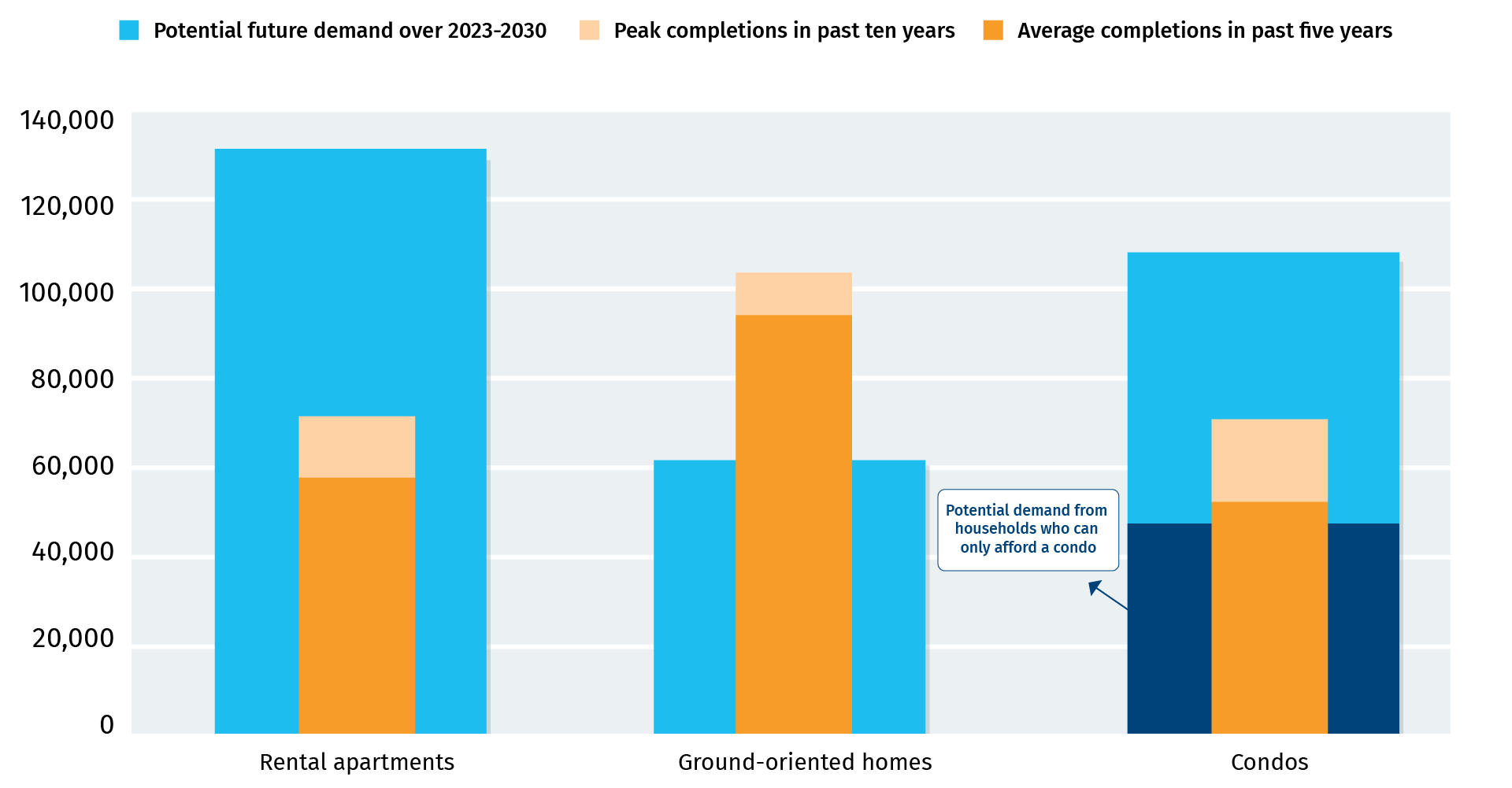

Stretched affordability will drive up rental housing demand to the point where housing construction must almost be entirely dedicated to the sector. Potential condo buyers would outnumber buyers of single-family homes by two to one by 2030. An eventual normalization of monetary policy and various policy measures should help more households become homeowners than estimates suggest. But the buying environment may remain challenging. Canada’s ownership rate (66% in 2021) is likely to drop.

Responding to growing rental demand requires a shift in the mix of housing Canada has been producing. Canada’s land development and building industry has a strong capacity to produce single-family and other ground-oriented homes like duplexes. The pace of ground-oriented home completions over the past decade would be able to match future demand for this housing type. Even recent condo completions could meet future demand from owner-occupants. But past completions for rental units where demand is poised to skyrocket are way off.

Increasing the social housing stock is also necessary. The magnitude of growth in social housing units needed to meet demand if affordability conditions don’t improve meaningfully is staggering. We estimate the 14,000 annual average addition to social housing stock since 2016 needs to jump more than four-fold to 57,000 every year to meet potential demand between 2023 and 2030.

Better yet, let’s incentivize them. The federal government recent elimination of the GST on newly built apartments (matched by cuts in PST in some provinces) is a step in the right direction. So are low-interest rates or other preferential terms on construction loans offered by Apartment Construction Loan Program (part of the National Housing Strategy) and the BC Builds program. A loosening of zoning restrictions applied to rental housing would also be good measure to encourage more rental development. Municipalities should align property taxes imposed on purpose-built apartment buildings with those applied to condos and low-rise homes. Development charges could be deferred or reduced for purpose-built apartment projects to make them viable compared to condo projects.

A special focus should be put on reducing the costs of social housing projects. For example, municipalities could waive development charges on projects guaranteed to remain affordable for at least 40 years.

Governments at all levels should make unused or under-used land they own available to affordable housing developers.

Post-secondary learning institutions must ensure that students get sufficient support services including housing. Increasing student housing would help relieve tensions in the broader rental market.

Addressing soaring rent by legally limiting increases is a solution that ultimately discourages investment in the rental stock. While the practice may benefit some tenants, it further hampers the market’s ability to rebalance and contain upward rent pressure from emerging in the first place.

Laws and regulations that are overly lenient toward delinquent tenants discourage investment in rental housing.

7. Expand the housing stock from within.

There’s potential to unlock capacity from existing housing structures and properties even though new construction needs do the heavy lifting. In many cases, this would be the quickest way to address the housing shortage. It’s hard to tell how many housing units could be created from our existing stock. However, if only 3% of the ground-related housing stock added a suite, it could possibly cover one-third of the future rental demand. Here are a few ideas to get more out of what we have.

Significantly restricting short-term rentals would be a quick way to bring in units Canadians can live in full-time. The scope is modest overall, but it could be material in popular neighborhoods in some of the largest cities. A study estimated there were 17,000 to 43,000 Airbnb listings that appeared to be dedicated short-term accommodations in 2019. It found that 8,000 to 19,000 of them were located in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver. Restricting these operations is what several municipalities (including Toronto) and provinces (Quebec, B.C., PEI) are pursuing.

Permitting or even encouraging the creation of secondary suites in basements, renovated garages or home additions would help boost the long-term rental supply. There’s significant potential to grow the so-called secondary rental market with 8.6 million owner-occupied single-detached homes, duplexes and row houses in Canada. Effective oversight must be in place to ensure compliance with building codes and other landlord-tenant regulations.

The need for office space has diminished as many Canadians embrace working from home. There are opportunities to transform some offices into homes—a trend that is emerging in several North American cities including Calgary. This potential shouldn’t be overstated, though. Studies in the U.S. have shown that converted units are contributing marginally to supply. These new units also tend to be at the higher end of the spectrum rent-wise.

In Ontario alone, over half of homeowners are over-housed (i.e., have too many bedrooms). Three-quarters of them are seniors. There could be ways to encourage households with extra rooms to rent them out to students, for example. The potential is significant with an estimated five million spare bedrooms in Ontario— equivalent to 25 years’ worth of construction.

![]()

Time is running out

Solving Canada’s housing crisis is a massive undertaking. It will take time and tremendous resolve by governments, industry, communities, and other stakeholders to reset the path we’ve been on for decades and address the policy missteps that caused house prices and rent to skyrocket.

The good news is many of the steps we outlined in this report have started to take place.

Governments in Ontario and B.C. are pursuing ambitious plans to grow their provincial housing stock by reducing the regulatory burden, speeding up approval processes and removing obstacles to build a more diverse housing mix.

Many cities—including Vancouver and Toronto—have set bold targets for new housing, including social housing, while reforming urban planning practices and development approval processes.

The federal government’s National Housing Strategy and programs such as the Housing Accelerator Fund should be creating positive changes that will result in more homes for Canadians.

Developers and builders are also showing more flexibility in working with authorities and partners to build homes people can afford amid capacity constraints and cost challenges.

However, more progress is needed and fast. Canada must grow its housing stock like never before, especially at the affordable end of the spectrum in rental and social housing.

If affordability remains close to where it is today, about 455,000 new social housing units would have to be created from now to 2030. That’s equivalent to all rental units built in Canada since 2018.

Improving Canadian’s quality of life will depend on bringing significant home and rent price relief.

For more, go to thoughtleadership.rbc.com/economics

Download the Report

Contributors:

Robert Hogue, Assistant Chief Economist

Rajeshni Naidu-Ghelani, Managing Editor, Economics & Thought Leadership

Darren Chow, Director, Content Strategy and Creative Production

Shiplu Talukder, Digital Publishing Specialist

Related Reading

document.querySelectorAll(‘main .accordion-panel button.collapse-toggle’).forEach((element) => {

element.addEventListener(“click”, () => {

setTimeout(() => {

var headerOffset = 100;

var elementPosition = element.getBoundingClientRect().top;

var offsetPosition = elementPosition + window.scrollY – headerOffset;

window.scrollTo({

top: offsetPosition,

behavior: “smooth”

});

}, 250);

})

})

window.dataLayer = window.dataLayer || [];

function gtag(){dataLayer.push(arguments);}

gtag(‘js’, new Date());

gtag(‘config’, ‘G-RMKF2F8DDS’);

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. The reader is solely liable for any use of the information contained in this document and Royal Bank of Canada (“RBC”) nor any of its affiliates nor any of their respective directors, officers, employees or agents shall be held responsible for any direct or indirect damages arising from the use of this document by the reader. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

This document may contain forward-looking statements within the meaning of certain securities laws, which are subject to RBC’s caution regarding forward-looking statements. ESG (including climate) metrics, data and other information contained on this website are or may be based on assumptions, estimates and judgements. For cautionary statements relating to the information on this website, refer to the “Caution regarding forward-looking statements” and the “Important notice regarding this document” sections in our latest climate report or sustainability report, available at: https://www.rbc.com/community-social-impact/reporting-performance/index.html. Except as required by law, none of RBC nor any of its affiliates undertake to update any information in this document.