- Immigration and shrinking household size will support Canada’s property market through the current correction.

- The flow of new permanent residents, already rebounding from pandemic lows, is set to reach record heights under new immigration targets.

- And as more Canadians opt to live in smaller groups, the number of households is on the rise.

- As these forces gain strength, over 700,000 more households will be formed in Canada by 2024 (compared to 2021.)

- The bottom line: Together, immigration and shrinking households are among the forces that will bolster Canadian housing demand and protect against a full blown housing crash.

It’s not just immigration: shrinking households will drive housing demand

Canada is in the midst of a steep housing correction. And though this cycle has yet to fully play out, it’s unlikely to morph into the type of prolonged spiral observed in the U.S. during the 2008 financial crisis. One of the main reasons: demographic demand for housing in Canada is strong—and it’s getting even stronger.

We expect the number of Canadian households to rise by 730,000 by 2024 compared to 2021, adding 240,000 new households annually. Immigration is key to this surge: Ottawa’s targets are set to bring in a record 1.3 million new permanent residents, adding 555,000 new households by 2024.

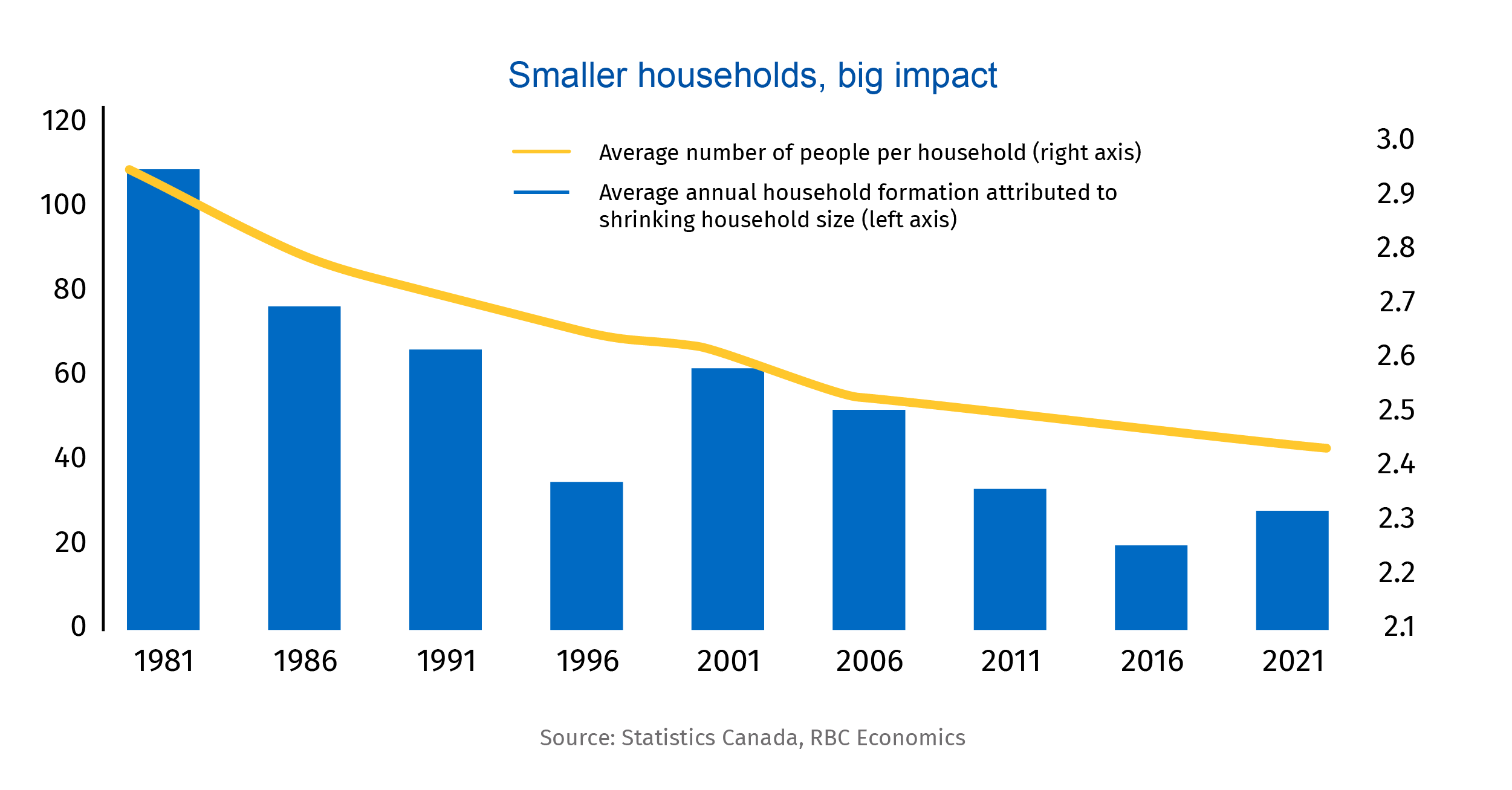

But another critical factor is the often overlooked, longstanding impact of demographic change, including households that have been getting smaller for decades. Even a relatively small decline in average household size has a big impact on the number of new housing units required to shelter Canadians. For example, over the five years leading up to 2021, the average household size declined by 0.02 people. That was enough to raise the total number of households by 140,000 (or close to 30,000 a year). This trend will be responsible for just under 90,000 of the 730,000 new households created by 2024—and will provide a significant boost in housing demand.

Why Canada’s households are getting smaller

What’s behind this squeeze in household size?

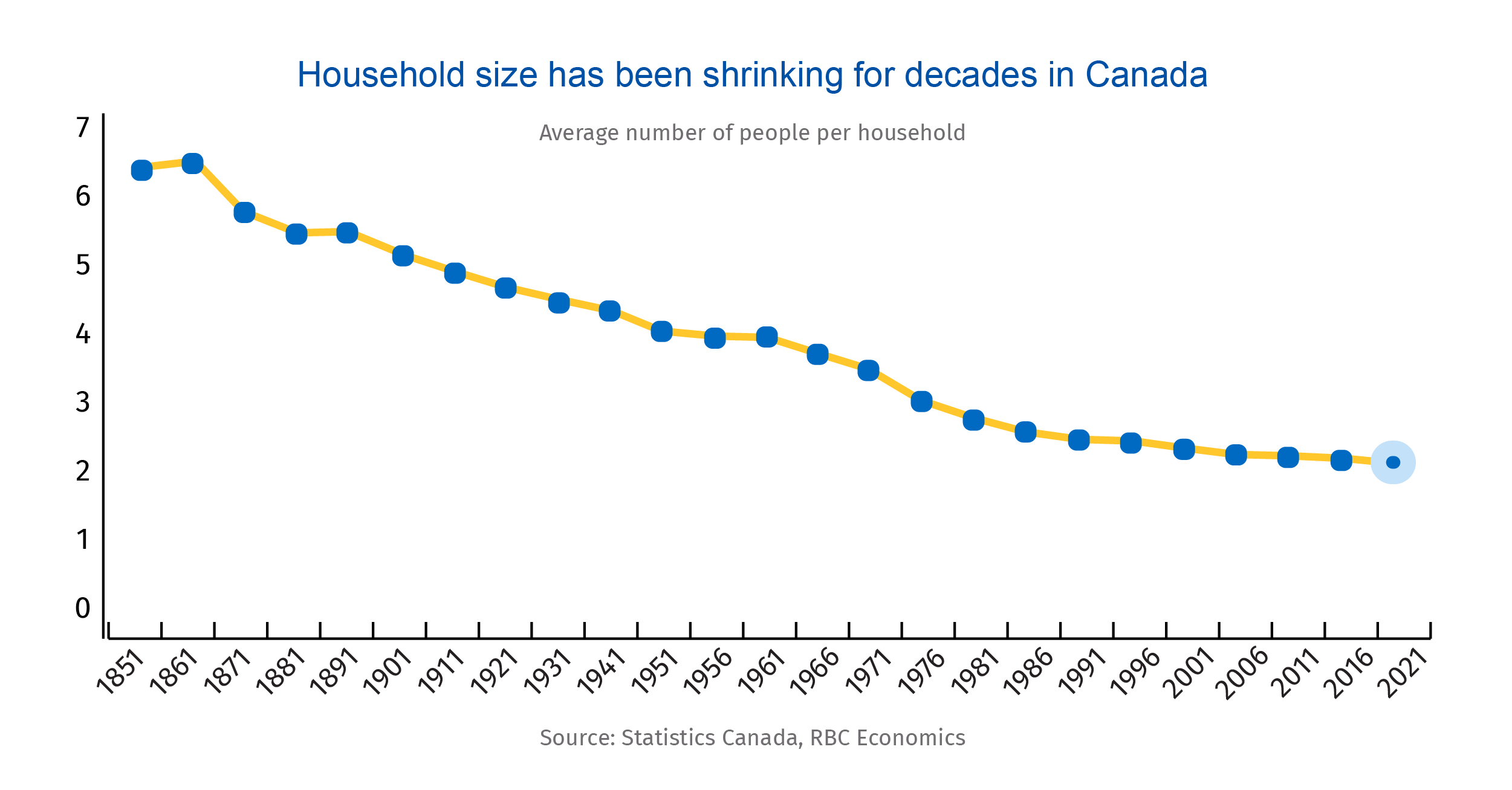

Canadian households have been shrinking since before Confederation. Historically, this was mostly attributed to parents having fewer children. In 1851, the average Canadian household had more than six people. By the early 1940s, it had fallen to 4.3 people and as of 2021, the average Canadian household had 2.4 members.

But since 2016, one-person households have become the most common, with nearly 30% of Canadians now living alone. Though much of this is explained by population aging, a growing share of young Canadians are also opting to live alone—and are starting their families later. The share of young adults aged 25 to 34 living as a couple fell to 43% in 2021 from 48% in 2011. And the mean age of mothers at the time of childbirth has increased by three and a half years since the early 90s.

Canadians who become parents later typically have fewer children, further perpetuating the trend of shrinking families. At the same time, as average male life expectancy increases, elderly Canadian couples are living together longer—though we will continue to see a rise in the number of widowed seniors living alone. As Canadian Baby Boomers age and live longer than prior generations, many will stay in their homes for longer.

Immigration and shrinking households will contain a housing spiral

These trends are gaining momentum. Young Canadians are staying in school longer, starting their careers later, and face greater housing affordability challenges than previous generations—all of which delays starting a family. And though immigration is rising—and newcomers are more likely to live in multigenerational homes—this hasn’t fully offset the broader shrinking of households. Over the last decade, the number of multigenerational homes has risen by close to 80,000 dwellings. But that’s only around 5% of new households. Meantime, the number of one-person households accounted for 44% of household formation (700,000 dwellings) over the same time period.

Due to immigration, Canada’s population is growing much faster than other countries—over twice the pace of the OECD average over the past decade. This surge, combined with shrinking household sizes, will strengthen demand for housing (whether owned or rented) and act as a powerful counter to sliding sales and prices—eventually putting a floor under the correction.

Robert Hogue is a member of the Macroeconomic and Regional Analysis Group, with RBC Economics. He is responsible for providing analysis and forecasts for the Canadian housing market and for the provincial economies. His publications include Housing Trends and Affordability, Provincial Outlook and provincial budget commentaries.

Carrie Freestone is an economist at RBC. She provides labour market analysis, and is a member of the regional analysis group, contributing to the provincial macro outlook.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More