For decades, RBC has engaged with Indigenous communities and we continue to work with them on our journey toward progress and reconciliation. The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was a clarion call that led to The Cost of Doing Nothing and subsequent work, including A Chosen Journey. Through our Climate Blueprint we are committed to sustainability and accelerating the transition to Net Zero. In these initiatives, we are listening and learning and using our platform to amplify Indigenous voices.

It’s now clear that the national priorities of Net Zero and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples are inextricably linked. In the same spirit, we expect RBC’s reconciliation journey will increasingly intersect with our climate priorities.

92 to Zero highlights the incredible value that Indigenous capital, knowledge and decision-making can bring to a Net Zero transition. We’ve recently launched a national initiative of “listening circles” led by former Assembly of First Nations national chief Phil Fontaine that this report will help inform and inspire—and lead to more from us in the years ahead.

Now, each of us must act to break down the ongoing systematic barriers that prevent the full realization of Indigenous capital, supporting reconciliation and climate action. We hope this report will propel us further down that path.

We acknowledge that RBC resides on the traditional and contemporary treaty, and unceded territories of Turtle Island (North America) that are home to many First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.

Key Findings

- Canada’s road to Net Zero will rely heavily on vital sources of capital held by Indigenous nations. RBC estimates Canada needs roughly $2 trillion in capital over the next 25 years, much of it from Indigenous sources—or unlocked by Indigenous partnerships, including ownership.

- An Indigenous-led approach to the climate transition, and economic opportunities toward Net Zero, will be essential to economic reconciliation.

- Specifically, to achieve Net Zero and economic reconciliation, Canada needs to leverage four forms of Indigenous capital:

What is 92?

To redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation, the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued 94 calls to action. The 92nd dealt specifically with business and reconciliation.

We acknowledge that RBC resides on the traditional and contemporary treaty, and unceded territories of Turtle Island (North America) that are home to many First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.

Indigenous communities can unlock green economic growth

For many Indigenous Peoples in Canada, braiding is a sacred act. It brings together seemingly disparate sinews, with the goal of building a stronger, more unified whole. Strands of hair, breakable on their own, become more resilient when braided together. Blades of sweet grass are woven and burned with sage, cedar, and tobacco, the ceremony strengthening the community, which in turn cares for the plant.

Similarly, to meet the generational challenge of climate change, Canada must weave together the critical strands of Indigenous capital to secure a durable Net Zero strategy.

This new approach is about much more than money. It includes natural capital—vast portions of critical mineral, solar and wind developments depend on access to Indigenous lands—along with growing Indigenous wealth (financial capital), traditional Indigenous knowledge (intellectual capital) and powerful Indigenous entrepreneurship and talent (human capital). Each is required to strengthen the whole.

To unleash this capital, Canada will need new tools for clean energy development. That means establishing stronger corporate commitments and incentives for Indigenous partnership, greater sharing of project benefits, and financeable models of Indigenous equity participation. It means developing investment criteria that incorporates Indigenous perspectives and more intentional development of Indigenous entrepreneurs and youth leadership.

Above all else, it means establishing a new approach to partnership, one that reinforces the role of Indigenous rights, leadership, decision-making and consent.

These concrete actions will pull growing sources of Indigenous capital toward Net Zero. They’ll also mobilize critical private capital, by building a foundation of predictable development, better environmental outcomes, and expansive social impact.

Meaningful partnerships can’t be rushed. But the demands of the Net Zero transition are immediate—and there’s only one opportunity to get it right.

The onus now is on everyone to move forward together.

Natural Capital: The path to Net Zero winds through Indigenous land

Canada comes to the global climate challenge with a unique set of advantages. Its landscape includes vast quantities of both conventional and renewable energy resources—assets that, while enviable, bring challenges. Even as the country continues to rely on oil and gas, and works to more sustainably produce it, it’ll need to begin harnessing the resources to power the clean economy of the future.

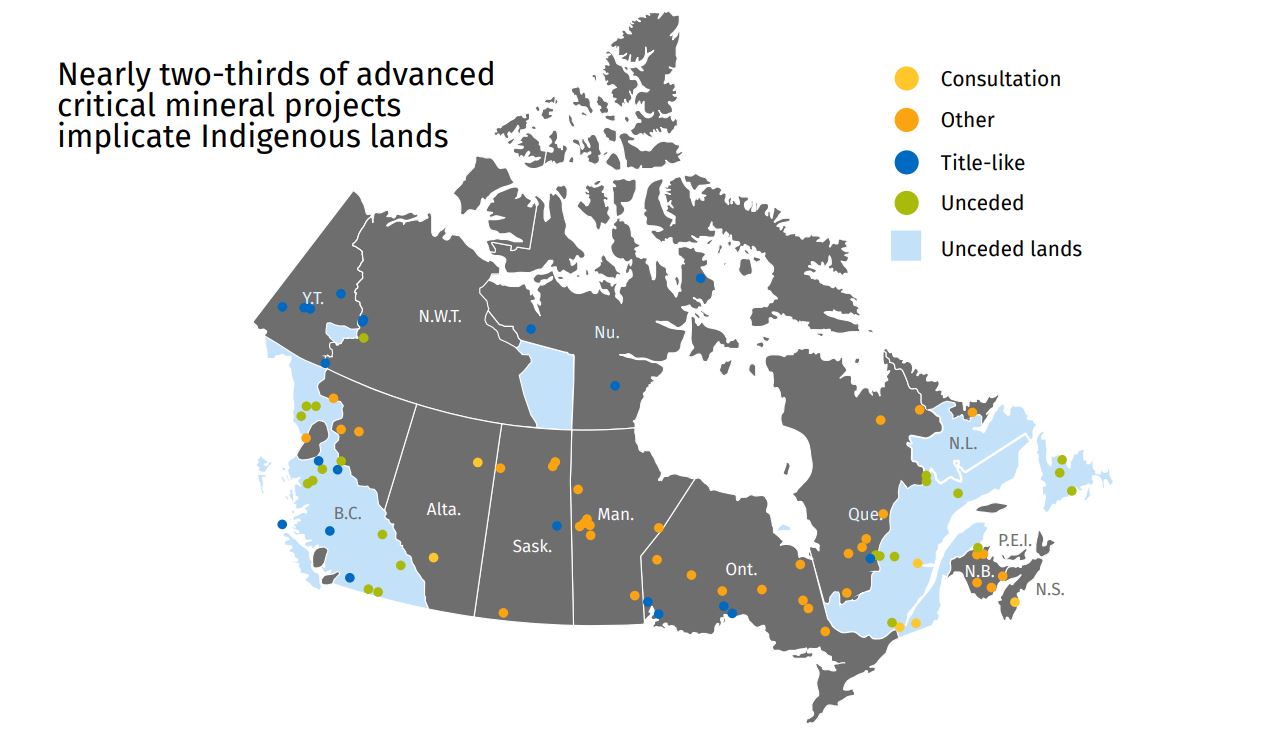

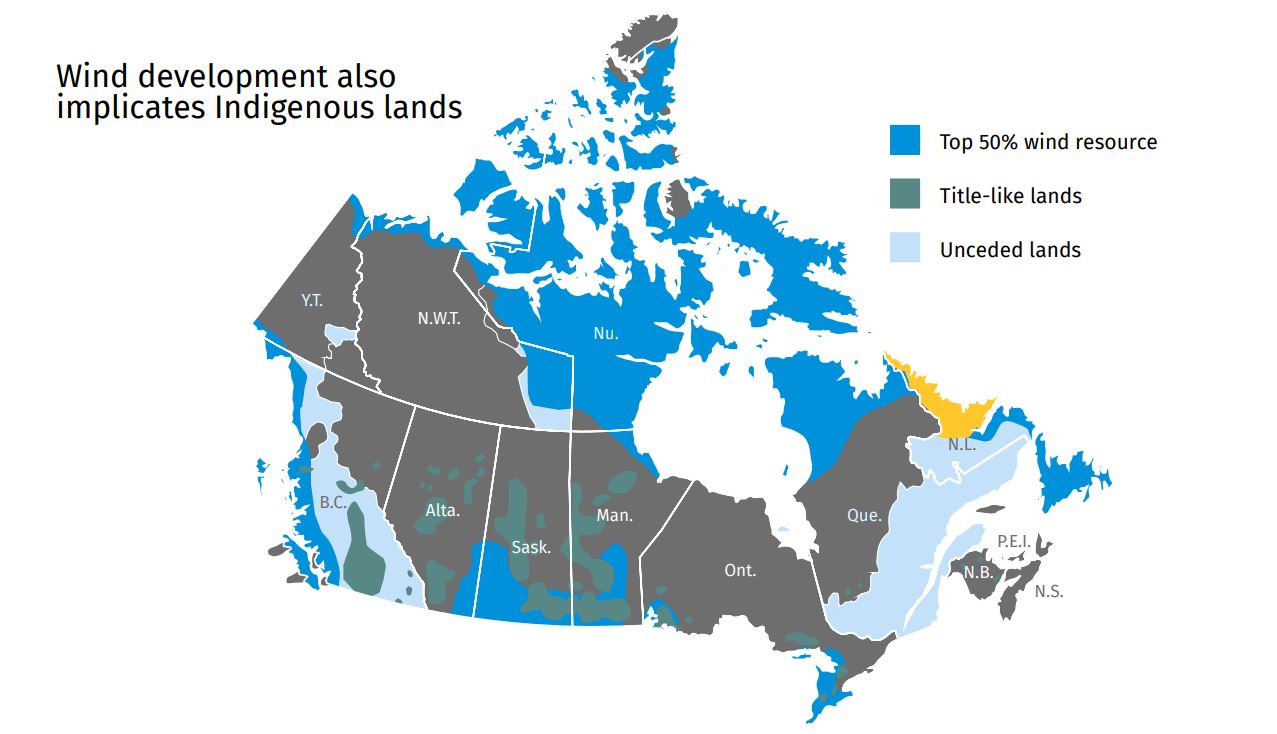

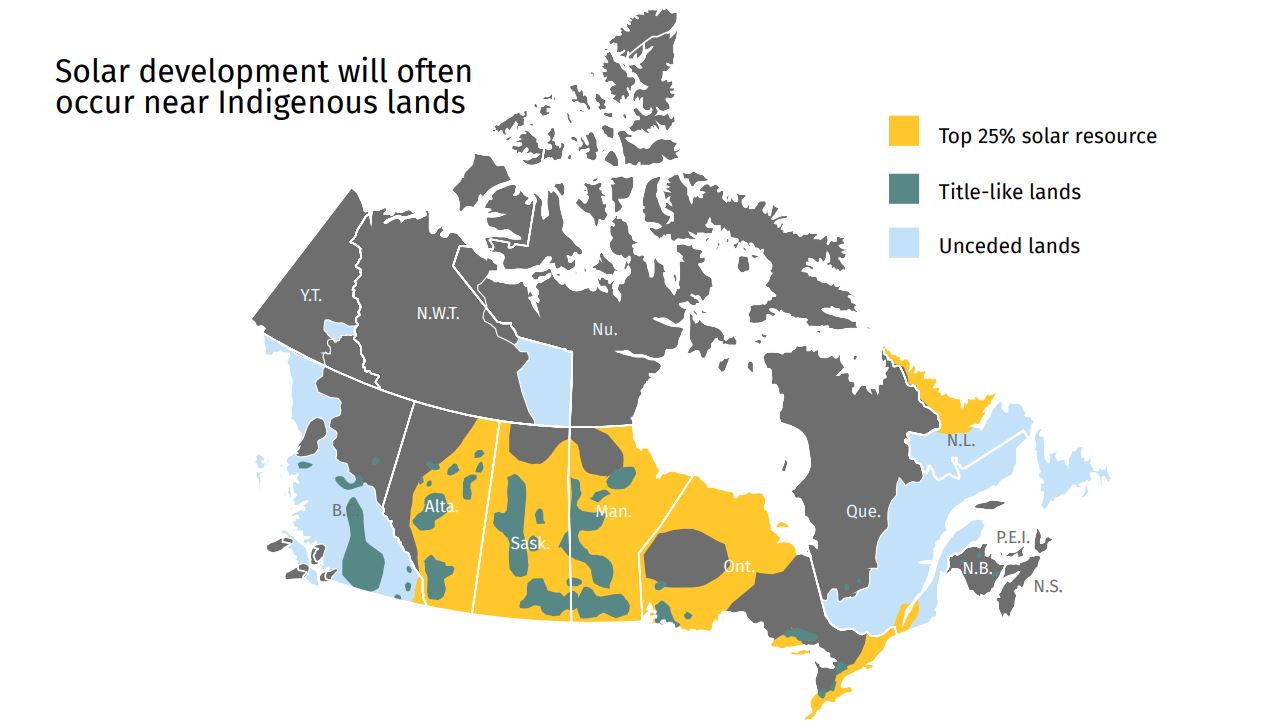

And these resources are attached largely to Indigenous lands. RBC research shows at least 56% of advanced critical minerals projects involve Indigenous territory. Top opportunities for renewables development also overlap with Indigenous lands, including at least 35% of top solar sites and 44% of better wind sites. And Indigenous rights exist over many other territories that will require engagement.

To include these assets in its Net Zero strategy, Canada will need a new model for Indigenous partnerships—one that begins with meaningful engagement and consent.

Indigenous land contains key resources

- At least 56% of the $60 billion in new critical mineral advanced projects involve Indigenous lands, including 26% within 20 kilometres of Indigenous reserves, settlement lands, and other title-like areas, and another 30% on unceded territories where Indigenous rights are asserted.

- At least 35% of the top sites for the required $30 billion in solar development are near title-like lands.

- And at least 44% of the better sites for the needed $135 billion in wind development are near title-like lands.

Indigenous communities have ‘a say’, but not decision-making power

Greater legal and political recognition of land rights has empowered Indigenous voices at the negotiating table for development projects, particularly in unceded and modern treaty territories.

These advancements follow decades of government policy that removed Indigenous Peoples from decision-making and deprived them of long-held land and treaty rights. This created a cycle of underinvestment, poverty, and trauma that persists in many communities today.

How Indigenous Peoples were isolated from decision-making

Early cooperation between distinct and sovereign settler and Indigenous groups created mutually beneficial trade and strategic military alliances that aided European survival on the land. But over time, official government policies of land dispossession, paternalistic suppression, and cultural assimilation took hold. The government never fully honoured original agreements and it removed Indigenous Peoples from the decision-making table.

It’s now clear that the national priorities of Net Zero and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples are inextricably linked. In the same spirit, we expect RBC’s reconciliation journey will increasingly intersect with our climate priorities.

92 to Zero highlights the incredible value that Indigenous capital, knowledge and decision-making can bring to a Net Zero transition. We’ve recently launched a national initiative of “listening circles” led by former Assembly of First Nations national chief Phil Fontaine that this report will help inform and inspire—and lead to more from us in the years ahead.

Now, each of us must act to break down the ongoing systematic barriers that prevent the full realization of Indigenous capital, supporting reconciliation and climate action. We hope this report will propel us further down that path.

We acknowledge that RBC resides on the traditional and contemporary treaty, and unceded territories of Turtle Island (North America) that are home to many First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.

As Indigenous communities regain rights and sovereignty, business methods are inching closer to the true spirit of initial cooperative agreements between Indigenous and settler societies, or

Treaties, that guided the sharing of land and living together in parallel.

But conflicts continue to erupt, including public demonstrations against development companies. While the courts have signaled a growing willingness to set precedent for consultation, they’ve also established that Indigenous rights are not absolute.

Government often navigates difficult decisions in the overall national interest. But this maxim has led to problematic policy and flawed corporate approaches to Indigenous engagement. Too often, Indigenous Peoples have been given only checkbox approval on planned projects that don’t respect their community values, governance, timelines, or consensus-building processes.

Resulting clashes have led to cancelled projects, runaway costs and timelines, and rushed planning phases that fail to leverage extensive Indigenous knowledge of land stewardship.

An oppositional approach is one way to pursue energy development. But it’s not the optimal one. Resulting court challenges, broken social trust, delays, and investment uncertainty pose a sizeable threat to Canada’s climate ambitions.

Striking true partnership

Some Indigenous leaders have told Canada’s business community they’re thinking about this in the wrong way. Rather than represent a project risk, Indigenous Peoples could bring something unique to the table. They can potentially improve certainty and returns, offer deep location-specific knowledge and better environmental and social outcomes. And as the rights of Indigenous

Peoples continue to draw international attention, their reintegration into clean energy development could emerge as a competitive strength.

“I think a lot of proponents are going to have to shift their mindset from thinking of Indigenous people as a risk to a possible source of capital and an enhancement to their project.”

Mark Podlasly

Director Economic Policy

First Nations Major Projects Coalition

Mark Podlasly

Director Economic Policy

First Nations Major Projects Coalition

To realize it, Indigenous communities must be engaged as true partners. That means including their voices, values, knowledge and decision-making from the earliest stages of a project. Sufficient time needs to be allotted for this process, similar to the months or years afforded for Western development work.

Meaningful engagement and consent is an ongoing exercise of building trust, sharing information, and acting to realign the terms of the partnership based on evolving priorities. It also includes the possibility of saying no—some projects will not align with community values, and they may have to be rerouted or in some cases abandoned.

The power of Indigenous equity

Indigenous equity ownership of new energy projects is rising. Equity improves the risk profile of projects, both through ongoing information sharing and the ability of both parties to shape their direction.

Equity participation can build intergenerational wealth and guide land stewardship. This aligns with the long-term sustainable world view of many nations and in particular, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Seventh Generation Principle, where decisions are partly determined by the impact they’ll have on the next seven generations.

By contrast, near-term commitments in many of today’s impact benefit agreements (around Indigenous procurement, employment, community investment or royalties) are increasingly out of sync with the priorities of Indigenous communities, especially in light of the valuable sources of capital they control.

Equity is not a universal solution. Some communities may not have the risk appetite or expertise to manage equity investment. Infrastructure development is complicated and risky, and project finance lenders may be wary of significant partners that lack major construction or operational experience. Certain projects that focus on transition fuels or non-dominant abatement technologies—like oil, natural gas, or carbon capture, utilization, and storage—could carry long-term risks.

And equity isn’t always an option for the Indigenous communities that want it. Even communities that have revenue-generating activities may find a portion of the equity contribution is unfinanceable by private lenders. For communities that lack any revenue-generating activities, the equity option is even further out of reach. Project proponents, financial institutions, and governments need to eliminate this equity financing gap. Greater capacity building and advisory services are then needed to support communities in making informed choices between different partnership arrangements, and negotiating the best terms.

“Our nation is not new to industrial development […] essentially we’ve sat on the sidelines and witnessed the destruction of our territory, our environment, and our cultural resources to being active partners within a process where we had a seat at the table.”

Chief Crystal Smith

Haisla First Nations Chair

First Nations LNG Alliance

Chief Crystal Smith

Haisla First Nations Chair

First Nations LNG Alliance

Financial Capital: Indigenous leadership will help fuel the $2 trillion transition

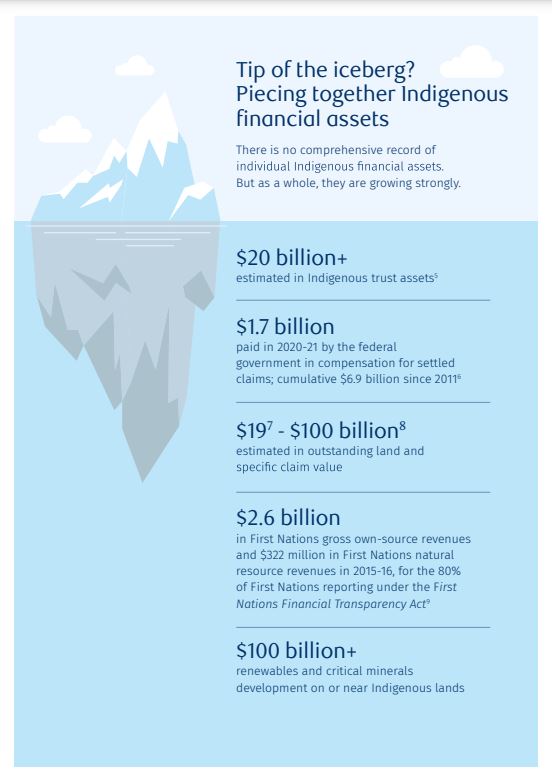

Large Canadian firms with $8 trillion in global assets have committed to Net Zero, yet annual spending on green projects is still far short of the $80 billion per year required. Indigenous financial wealth isn’t at the scale needed to lead financing of the $2 trillion Net Zero transition. But with more than $20 billion in trust assets and up to $100 billion in outstanding land and other claims, it can nevertheless make a significant impact.

The bigger opportunity rests in the power of Indigenous financial capital and consent to crowd in the larger private funding needed for Net Zero—by derisking projects, boosting returns, improving environmental outcomes, and increasing social acceptance. Mobilizing investors to support Indigenous-aligned responsible investment will accelerate this process while also enhancing economic reconciliation.

Indigenous assets cycle back into communities

Greater recognition and application of Indigenous land rights have added to the financial wealth of Indigenous communities. These additions stem partly from land claim settlements or compensation for past violations of treaty or other rights. With over 250 specific claims awaiting negotiation and over 160 currently under review, as well as ongoing litigation and land claims, further increases in these assets can be anticipated.

Distinct from individual wealth, these assets are for the benefit of the community, supporting spending on physical, social or cultural infrastructure, economic development, or disbursements to members. They are increasingly being used to decarbonize local communities, including Net Zero projects in the built environment, renewable energy developments or transmission lines that bring cleaner electricity to diesel-reliant remote communities, or equity stakes in sustainable projects such as transition fuel facilities or wind and solar farms.

The Senákw project on Squamish Nation reserve land in Vancouver—a 12-tower, mixed-use development—is the largest First Nations economic development project in Canadian history and Canada’s first large-scale net zero housing development . To be developed in partnership with a private developer, the Nation is contributing the land. Costing $3 billion to construct, it could generate $8-12 billion in revenue for the Nation over the leasehold life

While growing, Indigenous financial assets remain undersized, a result of the historic non-recognition of Indigenous rights and suppression of the Indigenous economy. There’s also significant variation in the financial wealth held by communities based on treaty status (unceded, modern, or historic), location (urban or remote) and proximity to major resource projects. For example, the Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh nations have major developments on their traditional unceded territories around and within modern day Vancouver. By contrast, a limited sample of 500 First Nations from 2015 to 2016 showed 50% had revenues below $3 million, whereas the top nation earned almost $100 million.

Formally recognizing the value of Indigenous partnership

Indigenous leaders can provide the greatest long-term certainty around infrastructure development. And Western developers and scientists are starting to recognize the value of Indigenous knowledge in project design.

Governments and leading project sponsors need to financially recognize the value Indigenous partners bring to the table. Fair compensation will lead to a growing Indigenous financial asset base that can be invested back into community wellbeing and position nations for Net Zero investment. That means finding new valuation models that go beyond lands leased or rights-of-way. Right now, communities that seek an equity share after the risky construction phase often purchase a stake in a more valuable project—but at a higher cost. This is despite their active participation in helping to de-risk it from the beginning. In terms of traditional knowledge, communities are often reimbursed for their time or monetary outlays, but not necessarily for their intellectual property as ‘consultants on the land’. Appropriately classifying these features as accretive to project returns may lead to their monetization, helping to close the Indigenous financial asset and equity financing gap.

Indigenous-aligned responsible investment

Successful Indigenous communities are investing in financial products consistent with their cultural values and using activist strategies to push companies to do better. They’re scaling their impact and building capacity through partnerships with like-minded investors. The National Aboriginal Trust Officers Association (NATOA), a resource and training organization, and Share, a responsible investment organization, have created the Reconciliation and Responsible Investment Initiative. It seeks to mobilize Canadian investors to “… use their voices and their capital to promote positive economic outcomes for Indigenous peoples including through employment, support for Indigenous entrepreneurs, increased partnerships with Indigenous communities and respect for Indigenous rights and title”10.

There’s a growing understanding that Indigenous entrepreneurs and communities could be a valuable focus for impact investing approaches. Also, that Indigenous factors, like Indigenous project co-development or Indigenous say in corporate governance, may be important to the overall performance of companies and projects. But while intentions are on the rise, the tools and regulatory framework to mobilize finance remain in the early stages.

- The ESG standards increasingly being deployed across capital markets have largely omitted Indigenous priorities and perspectives, and were developed without Indigenous input.

- Too often, Indigenous issues are considered an “S” factor in ESG modelling, which overlooks the singular legal foundations of Indigenous participation, as well as the unique environmental nature of Indigenous-led or -guided development.

- The $1.3 trillion dedicated sustainable equity fund market has no funds with an explicit focus on Indigenous issues.

- Investor demand has been insufficient to establish investment products aligned with Indigenous priorities.

- Concrete business commitments to Indigenous issues are not significant enough—or disclosed and verifiable—to build diversified products.

As the investment environment changes, corporate and investor inaction on climate and Indigenous priorities becomes increasingly salient to the bottom line.

“Investors are going to need to see this as not as some sort of forecasted or predicted risk. They’re actually going to need to see climate change as having material impact on assets that they own..”

Joseph Bastien

Share

Reconciliation and Responsible Investment Initiative

Joseph Bastien

Share

Reconciliation and Responsible Investment Initiative

Intellectual Capital: The power of Indigenous land stewardship and knowledge

Indigenous capital is more than natural and financial capital. Recognition of the value of Indigenous voices and knowledge can be a powerful driver of both economic reconciliation—and growth.

Generations of traditional Indigenous knowledge have shaped an approach to land management that ensures the long-term sustainability of ecosystems. Each community specializes in preserving the delicate interrelationships between people, plants, and animals in its traditional territory. This approach is holistic, anchored in the interconnectedness of the environment, well-being and culture. It’s about the principle of reciprocity and sustainability. It is not rigid, but evolving.

As Canada seeks to build a prosperous economy while also minimizing environmental damage, preserving biodiversity, and developing nature-based carbon sinks for climate management, Indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing will become critical competitive advantages.

Leveraging these assets can also extend economic opportunities to Indigenous Peoples that haven’t traditionally benefitted from land rights.

But it’ll mean embracing a different world view.

Two-eyed seeing leads to better outcomes

Etuaptmumk, or two-eyed seeing, is a Mi’kmaq principle that calls for seeing from one eye with the strength of Indigenous stewardship, knowledge, and ways of knowing, and from the other with the strength of Western tools and systems. Bringing both perspectives together can create thoughtful, and more profitable Net Zero solutions.

Uniting place-based Indigenous knowledge with Western scientific methods improves the outcomes of environmental studies for development projects. By itself, the traditional scientific approach may only offer a narrow window into the local environment and require advanced extrapolation—for instance, on the baseline migratory patterns of fish or how to restore a reclaimed project site to its original ecosystem from decades ago. Indigenous knowledge, acquired over centuries of climatic variation, can augment or contextualize this information, producing more robust conclusions. Similarly, Western methods can complement traditional knowledge. For example, tracking devices on at-risk local species can expand information on and understanding of their movements.

“[Mi’kmaq Ecological Knowledge] is a cumulative body of knowledge that is passed on from generation to generation, Elder to child and is dynamic. MEK draws upon the ever changing natural world—as ecological knowledge changes over time, and new experiences bring forward new understandings regarding the Earth’s ecology, the Mi’kmaq will continue to learn, grow and share, just as they have done for over ten thousand years.”

Mi’kmaq Ecological Knowledge Study Protocol

Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq Chiefse

Mi’kmaq Ecological Knowledge Study Protocol

Assembly of Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq Chiefse

Federal laws now require incorporation of Indigenous knowledge in the environmental assessment process, with interim guidance saying that traditional knowledge should be viewed as providing a framework “as complementary and influential information alongside Western science”.

But Indigenous knowledge does not yet have an equal place in environmental studies. Whereas Western science is afforded months, or even years, to do its work, assessment processes now often only have a short timeline for Indigenous input near the end. Indigenous communities often do not have this information readily available as it must be collected from knowledge-holders in the community, and they may be reluctant to share if trust is not strong. Others may want to produce their own traditional knowledge-based studies.

Human Capital: A new generation of leaders is driving innovation

Stronger say over local project development, growing wealth, and recognition of the value of Indigenous knowledge is empowering a new generation of Indigenous Peoples and entrepreneurs. The Indigenous economy, estimated at over $30 billion per year in 2016, is outpacing growth in the overall national economy and is poised to grow to $100 billion by 2024.

Driving change is a growing group of young, educated Indigenous leaders. These leaders are advancing new models of economic reconciliation and development. Supported by stronger land rights and growing capital, they’re pursuing an Indigenous-led approach to sustainable economic development that connects investment and community prosperity. They’re building networks with other Indigenous leaders past and present and often acting through increasingly influential Indigenous-led business and advocacy organizations, such as the Canadian Council for Aboriginal Business, First Nations Major Projects Coalition (FNMPC), Indigenous Resource Council, or National Aboriginal Capital Corporations Association (NACCA).

Many are heads of major economic ventures and are building a new model for the upcoming generation, which still sees limited Indigenous representation in corporate Canada. In 2020, only 0.3% of corporate board seats were held by Indigenous persons, despite their 4.9% share of the population.

Corporate Canada is increasingly seeking Indigenous perspectives and representation. As it does, it will be important that it doesn’t hoard Indigenous talent, especially from remote communities. Corporations that have a clear social purpose and use innovative models to share Indigenous talent with their communities are more likely to be successful.

Local talent can be a competitive advantage

The Net Zero projects brought by Indigenous leaders to their communities will have a powerful pool of human capital to draw from. And many communities are interested in economic partnerships that include long-term employment benefits. This means higher-value Indigenous employment and skills development that outlives the project, and includes opportunities at all levels including planning, design, construction, management, and operations.

This is also in the interest of project sponsors. For one, it’s a sign of the true partnership Indigenous leaders will be looking for when selecting collaborators. Additionally, in a world of acute labour shortages and fragile, cost-pushing global supply chains, a network of trusted local employees and suppliers delivers value. Building these networks takes time. But Canada’s energy system transition will be an intergenerational project.

The Net Zero transition can benefit from an Indigenous workforce that’s younger than for Canada as a whole. Indigenous youth are the fastest-growing population cohort, with their numbers expanding four times quicker than the non-Indigenous population. Indigenous people are increasingly pursuing postsecondary qualification, especially women, 52% of whom had a postsecondary qualification in 2016. Indigenous youth value their languages, identity and culture, and are confident in their foundational skills—including critical thinking, communication, or collaboration, which are all central to the future of work. The already strong employment of Indigenous people in Canada’s resource economy and skilled trades occupations, and greater proximity to remote areas, means an easier transition to the skills needed for green infrastructure and clean energy.

Meanwhile, Indigenous entrepreneurs are developing new businesses at nine times the Canadian average with 50,000 Indigenous-owned businesses across diverse Canadian sectors. Many of these businesses are promoting Indigenous values and knowledge, from Cheekbone Beauty—founded by Jenn Harper, an Anishinaabe woman whose line of high quality sustainable cosmetics is giving back to the community—to the SIKU mobile app, an Inuit-led social network to help hunters share real-time knowledge of ice conditions and animal behaviour.

Moving forward with reconciliation also means not hiding from the past or the impact that endures in so many Indigenous communities. All Canadians, including Canadian business, have a greater role to play in reconciliation, including supporting new approaches to education and pathways to employment, as we explored in our 2021 report, Building Bandwidth. Whether it’s apprenticeship and co-op opportunities for Indigenous students or capital for young entrepreneurs, a skills-centric approach to the climate transition will be critical.

“I think about the advancements [that Indigenous groups have] and it’s a small group thinking outside the box, thinking about innovation. What we need to figure out and address is how to bring everyone with us and continue to strengthen capacity in our communities.”

Chief David Jimmie

CEO at Squiala First Nation,

President Stó:lō Nation Chiefs Council

Chief David Jimmie

CEO at Squiala First Nation,

President Stó:lō Nation Chiefs Council

Capacity planning and supports are needed. Indigenous-led organizations are providing some of that—in addition to NATOA, First Nations Major Projects Coalition (FNMPC) and others, AFOA Canada provides capacity development in Indigenous management, finance, and governance. The Indigenous Leadership Development Institute Inc. (ILDII) builds leadership capacity in Indigenous people with specific training. But greater access and new partnerships will be critical.

More financial innovations are helping address the longstanding capital gaps between Indigenous communities and the rest of the country. It would take about $83 billion in capital to close the financing gap based on 2013 estimates. But Indigenous entrepreneurs still face barriers that other Canadian entrepreneurs don’t. Limits from the Indian Act and government underinvestment in assets continues to constrain the use of homes or other sources of collateral for conventional lending.

Innovative approaches can often work around this, but the complexity can scare off some lenders, or cause significant risk aversion in Indigenous lending. And with the need to access multiple government, Indigenous organizations, and private programs to obtain financing, application processes and timelines can be complex and time consuming.

A Way Forward

In her book, Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer describes the propagation of sweet grass as growing not from the wind or animals but by underground root systems called rhizomes. Having long survived unseen, the Indigenous community is now emerging with strength and taking hold of prosperity grounded in recognition of the essential strands that nourished it: natural, human, financial, and intellectual capital.

To get to Net Zero, Canada will need to bring this Indigenous capital together with non-Indigenous capital through positive intent and deliberate action. If this is done right, it can promote reconciliation and a prosperous Net Zero future for everyone.

Here are some key questions Canadians need to address:

- What are the steps of engagement that project proponents must develop with Indigenous communities to achieve and maintain consent for development, given evolving definitions of consent and community-specific priorities?

- How can Indigenous communities proactively communicate their internal governance structures, preferred engagement processes, and general posture or conditions for clean energy and infrastructure development?

- How can better equity participation models be developed to encompass the wide range of assets, ambitions and priorities across Indigenous communities?

- How can non-Indigenous and Indigenous-led financial institutions and governments fill gaps in the project financing needed to ensure meaningful Indigenous ownership?

- How can international ESG standards and metrics be adapted to incorporate Indigenous perspectives and Canada-specific context, including legal rights framework?

- What are the best practices for meaningfully hearing and integrating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in project decision-making processes as well as broader economic development strategies?

- How can Indigenous communities be supported in projecting the labour supply, skills, or supplier network needed to actively participate in economic development opportunities?

For more, go to rbc.com/climate.

Download the Report

Contributors:

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More