Finance Minister Freeland said Budget 2022 would be about boosting Canada’s long term economic growth. But her next fiscal blueprint risks being consumed by more immediate demands. The sharply rising cost of living, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the Liberal Party’s pact with the NDP have all added to the government’s spending priorities, potentially absorbing revenue surprises.

With increasingly limited fiscal space, the federal government will have to mobilize private capital to make Canada’s economy greener, more digital-ready and productive. Fortunately, households and businesses are sitting on a record 17% of GDP in excess savings and profits: ‘pre-loaded stimulus,’ in the words of last year’s budget.

The challenge now will be to maximize the sustainable growth dividend of this cash pile by encouraging it to flow into business capex and green household spending and investment.

Revenue surprises leave room for growth-focused investment….

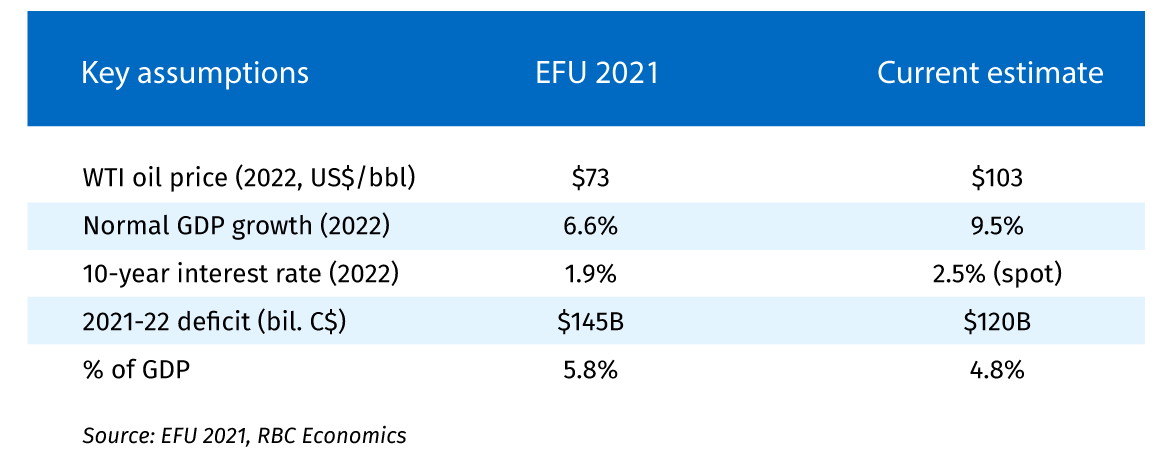

In its fall update (EFU 2021), a stronger-than-expected economic recovery and higher commodity prices left the government with unexpected fiscal room, allowing it to announce a number of new spending initiatives while still projecting lower deficits.

Three months later, that fiscal space appears to have grown. Strong revenue growth should make for a smaller 2021-22 deficit. On top of that, budget sensitivities suggest stronger nominal GDP should improve the near-term budget balance to the tune of $6 billion to $7 billion annually1. Higher interest rates will eat into some of this fiscal windfall. Still, it looks like the government has an opportunity to record smaller deficits sooner than previously envisioned.

(Mostly) Favourable Math

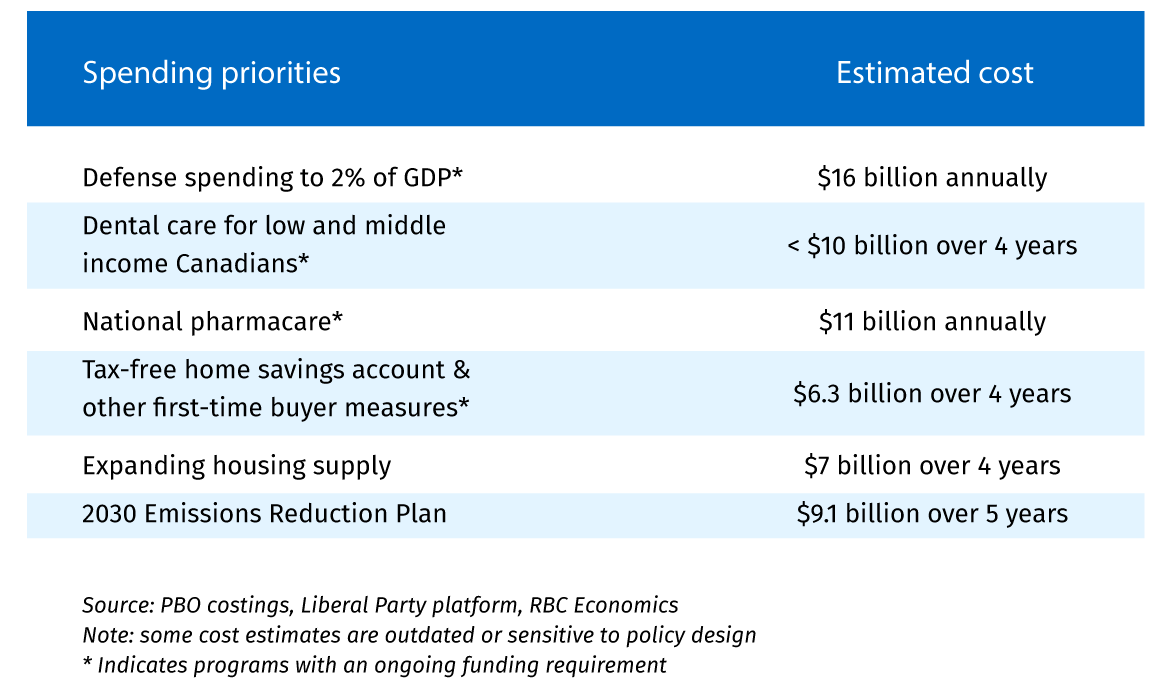

… but spending on defense, health care, cost of living, and housing could dominate

We think that’s unlikely though, given the new priorities commanding the government’s attention. Security concerns raised by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could prompt the government to raise defense spending from 1.4% of GDP closer to the NATO guideline of 2%. The Liberal Party’s agreement with the NDP was secured with promises of national dental care for lower- and middle-income Canadians and advancing a national pharmacare program. And this week’s updated Emissions Reduction Plan featured $9.1 billion in new, green spending—with a big ticket item like the previously announced carbon capture and storage investment tax credit still to be unveiled.

The government can make the case that previous actions will address cost of living concerns, including national childcare fee reductions and OAS enhancements for those over 75. Major transfer programs are indexed to inflation, although some take time to catch up. Still, Minister Freeland may feel the pressure to provide further household relief—as several provinces have already done. If this is the case, we hope these measures will be short-lived and targeted.

The government is all but certain to deliver on some platform housing measures. Those addressing speculation, transparency, or insured lending parameters are not big spending draws. But commitments to help first-time buyers and create more housing units will be costlier.

On the revenue side, the government could act on its campaign promise to impose higher taxes on large banks and insurers and higher income earners and on efforts to reduce the tax gap. These measures could raise $4.2 billion this year and $8.2 billion by 2025-26. But that revenue isn’t on the same scale as potential spending commitments, raising the prospect of further, more widespread tax increases to come.

Spending plans loom large

Limited fiscal space ahead will mean tough choices

Maintaining high levels of deficit-financed spending at this stage in the economic cycle risks exacerbating Canada’s inflation problem. Budget 2021 already allocated new fiscal spending of $28 billion in 2022-23 and $24 billion in 2023-24, ‘stimulus’ that notionally came with fiscal guardrails but has never been framed as contingent.

While some current sources of price pressure are global in nature and largely beyond the government’s control, broadening inflation and low unemployment suggest Canada’s economy doesn’t have much room to absorb additional spending. With the risk that the Bank of Canada is already behind the curve on inflation, interest rates might have to rise faster or further to offset any excess fiscal stimulus.

A rising rate environment also makes the government’s medium-term fiscal math more challenging. With 10-year yields up more than one percentage point since the fall update, there is less scope to run deficits while keeping debt-to-GDP on a downward trajectory (the government’s loose fiscal anchor). Furthermore, with yield curves flattening in Canada and the US—an oft-cited early predictor of recession—there is growing concern that the next downturn might be within the government’s projection horizon, making the case for a return of risk adjustments in the budget projections.

Private capital is the key to future economic growth

Private capital will be critical to addressing the long term challenges of labour shortages and shifts in spending, investment, jobs and worker skills prompted by increasing digital adoption, remote work, more ageing-related services consumption and decarbonization.

Businesses that simply return to pre-pandemic norms of returning profits to shareholders could limit domestic capital spending, while excess household savings spent on goods, services and real estate risks exacerbating cost of living and housing affordability pressures.

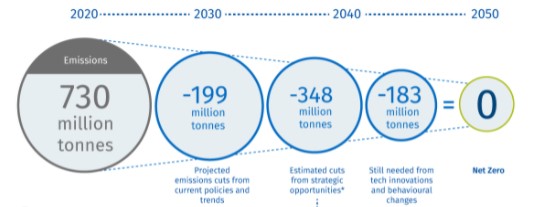

Alternatively, directing as much of that capital as possible toward the Net Zero transition—which itself could cost $60 billion to $80 billion a year—and digital readiness could help close Canada’s business investment gap with peer economies and, in the right policy environment, push innovation and productivity.

Businesses need regulatory certainty, co-investment structures, and de-risking

Despite Net Zero targets, many sectors are not investing enough in abatement because of poor project economics, immature technologies, and long run uncertainty. And without innovation, Canada won’t reach its Net Zero goals. Clean tech companies need to develop new technologies, while Canadian firms need to take on the risk of adopting and executing them. To make that happen:

Nearly 50% of emissions cuts are technologically feasible now, but more is needed

Households need green investing and residential investment options

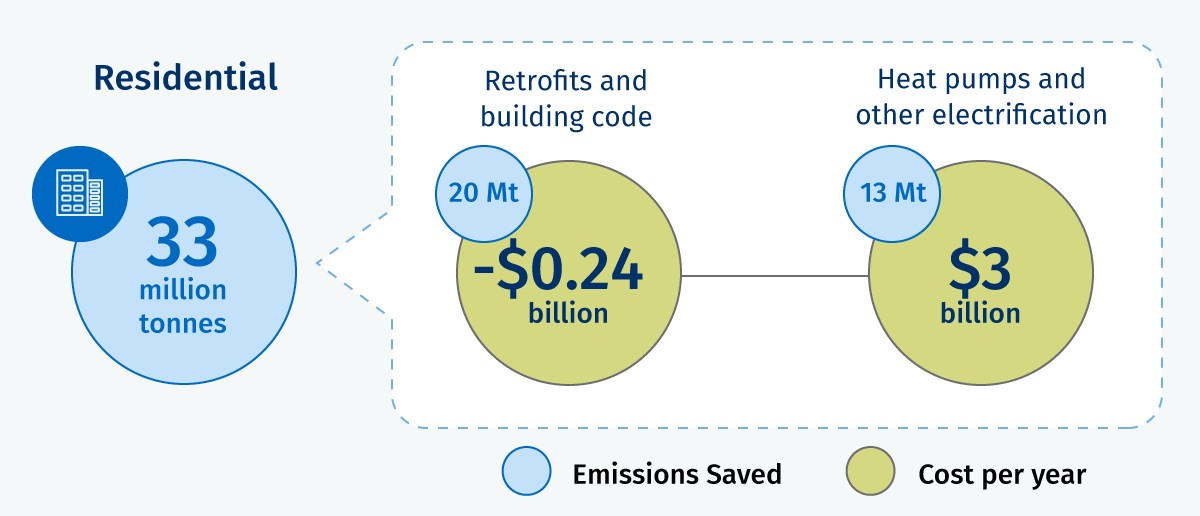

The concentration of pandemic savings and wealth gains is among higher income Canadians—supporting increased investment in assets. But that investment needs to be more Net Zero aligned. Despite recent growth, dedicated sustainable funds comprise only about 2% of public equity fund assets in Canada. Meanwhile, households are not investing in housing retrofits. This could be due to insufficient financial incentives or, for projects with net savings, daunting upfront capital costs, long paybacks, and inconvenience.

Residential building emissions could be eliminated for $2.5 to $3.5 billion annually

Note: Residential building emissions of 33 million tonnes CO2 equivalent remaining in 2030

Prudent fiscal management supports business and household confidence and investment

Last year a majority of firms said they would invest more than before the pandemic. Last fall’s recovery of non-transport machinery and equipment and intellectual property investment was an encouraging early sign. But growth in these areas slowed toward the end of the year.

New economic uncertainties could weigh on confidence and investment. Geopolitical turbulence, inflation and rising interest rates, and potential concerns about federal tax increases could all lead households and businesses to hang onto their savings, rather than invest.

Through a strong growth-focused tilt and prudent fiscal management, including targeted new spending, limits on deficit finance, and leftover fiscal space to deal with unexpected events, the government can help contain these concerns.

1. All figures in CAD unless otherwise indicated.

Cynthia helps shape the narratives and research agenda around the RBC Economics and Thought Leadership team’s forward-looking economic and policy analysis. She joined the team in 2020. Previously, Cynthia was an executive at Finance Canada, most recently heading a team responsible for housing finance policy covering housing-related risks, mortgage lending and funding markets, and the commercial activities of Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. She also has experience in current economic analysis and fiscal policy. Cynthia holds an M.A. Economics degree from the University of Toronto.

Josh Nye is a senior economist at RBC. His focus is on macroeconomic outlook and monetary policy in Canada and the United States. His comments on economic data and policy developments provide valuable insights to clients and colleagues, and are often featured in the media. Josh joined RBC Economics as an economist in 2012. He holds a bachelor of arts (honours) in economics from the University of Western Ontario and a master of science in economics from the London School of Economics.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More