The Issue

The pandemic has created a historic crisis for Canadian colleges and universities. It could present a significant opportunity, too. The widespread use of online learning platforms and tools offers educators a chance to reach a global body of students that could far exceed Canada’s current market.

It won’t be easy – other countries are eyeing the same opportunity and our schools will need to invest to grow, at a time when they’re being asked to cut. But as Canada pursues a knowledge-driven economic recovery, the digital export of post-secondary education could attract talent, create high-value jobs and help colleges and universities reimagine themselves in a pandemic-disrupted world.

POV

The global spread of COVID-19 shocked international education; and it’s not clear how quickly it will recover. So far this year, just three-quarters of the 2019 level of international students have arrived, while the number of study permit applications has plummeted, risking some of the estimated $22 billion in annual contributions these students make to our economy, and straining a sector that supports an estimated 170,000 jobs.

The fiscal impact of lost international student tuition is already hitting colleges and universities. Colleges and Institutes Canada expects only about a third of 2019’s level of new international students this fall. And rising deficits are leaving provinces with fewer resources to fight economic fires.

A concerted effort – among our schools, provinces and federal departments – is needed to resume Canada’s leadership in attracting international students, whose ranks numbered 642,000 at the beginning of 2020. Expedited visa processing, ensuring safe housing and broadening recruitment efforts will be critical.

Yet, international education is also ripe for new models. At the peak of national lockdowns, some 1.6 billion students were pushed out of school, prompting a shift in preferences toward distance and online learning. Among the nearly 300 million new degree-holders we’ll see globally by 2030 – double today’s number – many more will earn their credentials online.

Reaching these potential international students through a hybrid post-secondary model – online at entry, and on-campus at completion – would allow Canada’s universities to be key players in this growing sector. Consider the potential of a collective push among our universities to create a global “Canada U” program. Students would earn credits remotely from their home country, gaining language skills, career guidance and virtual work-integrated learning opportunities – becoming strong candidates to secure admission to upper year studies at a university in Canada.

Key Numbers

The global pandemic slowed student arrivals

Through June 2020, student arrivals among our top-10 source countries fell 26% compared with 2019. More troublesome was the 60% drop in new study permits received by IRCC in April, May and June, and the slow rate of visas processed – only about 10% of last year’s volume was completed this spring.

Yet, internationally mobile learners are motivated to continue studying abroad

COVID lockdowns have discouraged only 5% of international students to fully abandon studies. The majority (54%) are inclined to delay their education by up to 12 months in hopes of starting studies on-campus. Only three in ten plan to begin studying online first.

Number of young graduates set to double by 2030

Asia will produce new graduates at break-neck speed, accounting for more than half of young degree holders over the next decade. The surge will be largely fuelled by China and India, where the number of graduates will grow to 81 million and 70 million respectively.

Global middle class to add 1.7 billion people by 2030

If the COVID recovery is broadly inclusive, the global middle class could swell to 5.7 billion within 10 years, leading to higher post-secondary enrolments, though faculty and funding constraints in the global south may slow institutional growth. India – Canada’s largest source of international students – could see some 600 million move to middle income levels. Meanwhile, Ethiopia, Angola and Cote D’Ivoire could together add over 20 million to the middle class.

Online cross-border education market reaches double global learners

An estimated 13 million students are earning credits online from a foreign institution. This is double the roughly 6 million on-campus international students in 2019. Canada (12%) has been the third most popular destination for on-campus international students, behind the US (21%) and Australia (13%). But it remains a minor player in cross-border online learning.

Key Questions

1. How could an online focus strengthen Canada’s international education strategy?

Online education was absent from Canada’ international education strategy, released in August 2019. Just six months later, the federal government moved quickly to allow foreign students to complete up to 50% of their program online from their home country. While this was intended to shore up existing students amid the pandemic, it opens the possibility of a new approach to our global education engagement.

Canada’s universities have already made significant investments in remote learning methods and technology, having moved 1.4 million students online this spring. Left fragmented, these resources can serve the immediate needs of schools; but combined into a unique international program, they could magnify their reach.

Canada U would engage more students in more places, combining the flexibility of a MOOC, the rigour of a Canadian credential and the appeal of experience in the Canadian workforce. Broadly, here’s what it could include:

- Open, rolling enrolment for early-year online studies in their home country.

- Lower per-credit tuition costs, driven by the scale of massive global enrolment.

- Opportunity to accumulate credits towards a Canadian credential, or transfer to a domestic university.

- Canadian based faculty, and remote counsellors for academic, career and language development.

- Networking opportunities via Canadian trade offices in their country or satellite campuses.

- Chance to undertake remote work-integrated learning (WIL) with a Canadian employer.

- Opportunity for admission to on-campus learning at a Canadian school, once student has achieved equivalent credits to 50% of desired program.

Such an approach could open Canadian education to millions of young, mobile learners.

This would be no small undertaking. It would require unprecedented collaboration among our universities to provide course instruction and materials, with supports from federal and provincial governments to build digital infrastructure and global marketing, and among provincial credit transfer bodies to ensure smooth academic transitions.

2. How big is the online education market?

The OECD estimates that over 13 million students participate in cross-border online education, through both formal institutions and online platforms. The majority of these learners – while benefiting from the convenience of online studies – are not putting those credits toward a degree.

The UK has the largest number of remote international students working towards a degree – at 120,000 or about 12% of their enrolled foreign students. The culture of open distant learning (ODL) has been a key part of the UK’s strategy, cultivated across the Commonwealth – with the Open University in the UK claiming more than 2 million global graduates. By contrast, in the US, only about 5% of international students are based outside the country, and at Canada’s largest online-only school, Athabasca University, just 3% are international students.

The most significant growth over the last decade has been among MOOCs, or massive open online courses, that offer short-term courses. Though characterized by low course completions and poor student retention, their use has spiked amid the current economic uncertainty as learners seek to upgrade skills.

One of the largest platforms, EdX, claims to have had 33 million learners – nearly 70% from US and Europe. New entrant Lectera is launching a multi-lingual, fast-training program focused on workplace skills to reach global students. Google is entering this space too, providing fast-track online learning for job-focused skills to compete with traditional college diplomas.

Developed by MIT and Harvard, Edx has successfully bridged MOOC and traditional education with its MicroBachelors and MicroMasters programs, where students from anywhere can earn credits online, fast-tracking their learning when admitted on-campus. The success of these efforts demonstrates the potential for a “Canada U” program.

3. Do international students want to study online?

International students prefer– by far – to study on-campus, when possible. Surveys have repeatedly shown a strong desire among these learners to transition to the Canadian job market, with 70% intending to work here after graduation. Only the reputation of our education system (82%) and perception of a safe, tolerant society (79%) rate higher.

Yet, when we look at those who study primarily online, students in emerging countries appear to have a higher motivation to earn foreign credits online. Among MOOC students in Colombia, Philippines and South Africa, 49% completed at least one course; among those employed, it jumped to 70%, a 2016 survey found. By comparison, only 5 to 10% of MOOC students in the US and Europe will complete their online studies.

A Canada U could achieve a balanced approach of online and on-campus; offering accessible remote learning to many, with a pathway to completing studies at a Canadian school.

4. Where is the demand for greater post-secondary education?

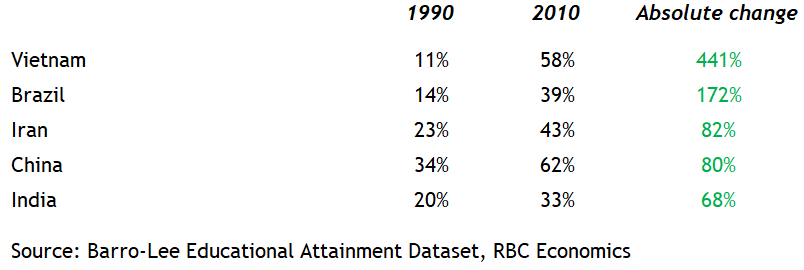

Among Canada’s top originating countries of international students, five have seen enormous growth in high school completion that hasn’t been matched by post-secondary achievement: Vietnam, Brazil, Iran, China and India. Among them, the proportion of adults (over 25) with only a high school diploma jumped between 1990 and 2010.

Upper Secondary education completion among adults (25+) without tertiary education, select countries

This growth shows two things. First, the value of high school completion is rising in developing nations. Second, there has been a slower capacity to convert these learners to post-secondary degrees. It’s no surprise either that the top originating countries of international students are also source countries of new Canadians; last year over 11,000 new permanent residents previously studied here. For Canada, education exports have led directly to talent imports.

Online education can attract more international students than traditional on-campus education by lowering the high financial barriers of tuition, travel and housing. Cost will be a key factor for families arriving into the middle class. This year alone, currency pressures have seen the Canadian dollar appreciate greatly against the Brazilian Real, Nigerian Naira, Ethiopian Birr, Russian Ruble, and slightly against the Indian Rupee and Chinese Yuan – boosting tuition costs.

What to Watch

- As colleges and universities reopen, and travel restrictions ease, will applications to study in Canada return to pre-COVID levels? Do we have enough capacity to promptly process applications?

- How will universities perceive their new online education resources, as strictly emergency spending or a potential growth opportunity? Can schools collaborate towards more shared online resources?

- To appeal to global students, will universities attempt a larger physical presence abroad, through satellite campuses or local partnerships?

- How can the intellectual property of online education be secured when entering markets with poor censorship or legal regimes?

Key Stakes

Education is a global social good. It is also a potent global market. The two concepts should not be separated. Canada has an excellent reputation abroad for high quality education; it’s one of the things we do best, with the highest rated tertiary education among the OECD and an already impressive share of international students choosing to learn here.

In the increasingly global knowledge economy, education is one of Canada’s greatest competitive advantages. Our deep alumni network of foreign graduates helps foster business networks abroad and strengthens trading relationships. Our robust student work permits lead to strong talent acquisition as a pathway to permanent residency. As Canada looks to rebuild for the 2020s, international education must be a key plank in our national strategy.

Canada U is one idea to help us get there. Embracing this bold venture will mean breaking down the artificial barriers between our higher education institutions and provinces to promote a collaborative, platform approach to international education. It will also require new funding to assemble the necessary technology, faculty and global marketing to make it a success, without clawing back existing transfers to our universities.

There is no shortage of competition in international education – from traditional universities to tech upstarts to growing domestic higher education – but Canada is uniquely placed to lead (if it wants to).

How the COVID-19 Crisis will Transform Higher Education

This report was authored by John Stackhouse, Senior Vice-President, and Andrew Schrumm, Senior Manager, Research, in the Office of the CEO

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More