The Distribution Gap

From office towers and shopping malls to stadiums and campuses, much of our economy was built through the 20th century on a model of centralization. The COVID crisis decimated that, at least for a time, allowing us to work, shop, watch and learn from anywhere.

Navigating 2021 will require Canadians to continue to build that decentralized future—and rebuild some of the centralized model that remains a powerful driver of innovation, efficiency and diversity.

Whatever shape and speed the recovery takes, the Canadian economy will continue to blend past and present, physical and digital, further dispersing economic activity and potentially ushering in a new era of decentralization.

The convenience—and for some, the opportunity—of the distributed economy is extraordinary. But so too are the consequences.

It’s already clear that, while many households and businesses continue to thrive, others are falling behind. If the 2020s indeed become the decade of distribution, it could bring heightened pressures for redistribution, too.

In the charts that follow, we explore the transformation and how it may influence consumers, business and policymakers in the coming year.

The economy isn’t poised to return to pre-pandemic levels before 2022. But the shocks have varied across industries and regions. Some sectors, including manufacturing, have shown their models still work. Other sectors, notably retail, are accelerating into a new period of growth and innovation. Others are discovering their legacy models may not get another chance.

To bridge this gap, Canadians will need to consider:

- Addressing long-term unemployment in sectors that rely on centralization, and the close proximity of people.

- Transforming skills programs so less-educated service workers are ready for a digitally driven economy.

- Building new approaches to supporting female employees and entrepreneurs, who have been disproportionately impacted by the crisis.

- Assisting businesses and communities to build the digital infrastructure and skills needed to thrive in a distributed, platform-based economy.

- Investing in natural resource sectors, including energy, to develop new technologies for firms and regions to lead the transition to a net zero economy.

- Redesigning cities, towns and communities to absorb and support a redistributed workforce.

- Reimagining education to develop the skills for a redistributed world.

Emergency relief and stabilization programs kept the economy, households and most businesses from a worse fate in 2020. Significant support will be critical to bridging the economy to a vaccine roll-out. But a fiscal exit strategy will be needed before too long—to avoid over-heating the economy, and to put government finances on a sustainable path.

The federal government’s 2020-21 Fall Economic Statement focused on the more immediate challenge of supporting firms and households trying to manage the transition. As a recovery takes form, the government will likely shift its focus to more structural forms of stimulus, from economic infrastructure to a transformation of social supports, from childcare to eldercare. The speed and design of this strategic stimulus will be critical to its impact on competitiveness, productivity and long-term growth.

In the years ahead, advanced technologies will play an even greater role than they did in the crisis, when online work and learning became as normal as online shopping and gaming. Canada will need a new generation of skills, and a new kind of social infrastructure, to enable the entire economy to thrive in a more distributed world, where anything can be done anywhere at any time.

It will be Canada’s chance in 2021 to turn a historic crisis into a historic recovery, by seizing on a new and evolving distribution of ideas and opportunities.

2021 in 21 Charts

![]() Beating the Virus Means Boosting the Economy

Beating the Virus Means Boosting the Economy

1. Vaccine will shorten the pain of a long recovery

What we’re seeing: The prospect of multiple effective vaccines in the first half of 2021, at least for vulnerable people and frontline workers, has boosted hopes for a quicker recovery. But a reopening of the economy—and even an unleashing of pent-up demand—won’t be enough to bring GDP back to its pre-pandemic state in the coming year. The hardest-hit sectors—restaurants, hotels and conference centres, for instance—will only pick up in a sustainable way after the virus’s full risk has faded. The scar tissue of permanent business closures may delay a full recovery until at least 2022.

What it means: There remain several big risks to 2021 growth. The distribution, effectiveness and public acceptance of vaccines are still question marks. The structural damage, through long-term unemployment and delayed investments, could also impede any rebound. Until public safety and economic confidence are established, large-scale fiscal and monetary stimulus will continue to be needed. Fiscal programs in particular are expected to focus on the pandemic’s lasting damage—to displaced workers, small businesses and sectors that rely on the large-scale gathering of people.

2. China, struck first, leads the global recovery

What we’re seeing: The virus started in Asia, swept through Europe and the Middle East, and then hit North America. Economic recovery started to show the same patterns but is diverging again as we head into 2021. China has roared back, thanks to effective control of the virus and focused government supports. The country’s industrial production returned to strength, as did its exports, partly to meet stimulus-fueled demand for consumer goods in Asia and the West. More services-centric Western economies have lagged, with the second wave adding further pressure in Western Europe and the U.S.

What it means: Virus containment and economic recovery are inextricably linked, and industrial composition matters, too. Economies with larger services sectors, including Canada’s, won’t fully recover until they can turn the corner on COVID. Once businesses in hard-hit industries are able to operate normally, pent-up consumer demand should help cement the recovery.

3. The long grind back: recovery will be uneven across industries

What we’re seeing: The first months of the crisis were nearly universal in their pain, causing almost every sector to decline. The early recovery has been much more uneven, which is likely to continue well into 2021. Manufacturing bounced back as consumers bought more cars and as businesses invested in protective equipment and supplies. Higher-value services, including finance, real estate, education and healthcare, also showed resilience, while sectors that rely on social gathering and travel—retail, restaurants and accommodation, especially—continued to struggle, with employment lagging GDP.

What it means: It’s not clear why GDP and employment haven’t recovered in tandem. Some firms will continue to use the recovery to drive efficiencies, and invest in machinery, equipment and technology over labour. Others may still not have the capacity to bring employees back to work safely, despite healthier order books. To the extent the pandemic permanently alters consumer preferences and the business landscape, recovery among some industries or their employment levels may remain incomplete even after the lockdowns are lifted.

4. Canadian energy, travel exports face steepest climb

What we’re seeing: Shutdowns, border closures and disrupted supply chains weighed heavily on Canadian exports during the early part of the pandemic. But the factory sector has been less impacted by second-wave restrictions, and strong demand for goods rather than services has helped non-energy exports. The halting recovery of energy demand—and a massive shock to global oil prices in 2020—continue to drag down energy exports. Tourism and travel remain limited by border closures and quarantine requirements.

What it means: Canada’s services sector isn’t just domestically focused; hard-hit industries like accommodation and food services are suffering in part from a lack of tourism. Recovery in these export sectors will depend on not just Canadian but global success in containing COVID. And while this would lift energy volumes and prices from pandemic lows, the energy sector faces an uncertain future. Renewable power prices are falling, and governments globally have committed to billions in green investments aimed at decarbonizing economic activity.

![]() Job One Is Creating a Broad-based Recovery

Job One Is Creating a Broad-based Recovery

5. Wages of $800 a week mark a dividing line

What we’re seeing: The COVID crisis has triggered some of the most unequal consequences for Canadian workers of any recession. Those at the bottom end of the wage scale, earning less than $800 a week, have borne the brunt of job cuts. Many of these low-wage/low-skill workers are in the hard-hit sectors of accommodation and food, transportation, retail trade, and construction, which together accounted for 65% of the decline in hours worked since the pandemic began.

What it means: This deep division in workers’ experiences has raised concerns about a starkly uneven, or K-shaped, recovery. On the upward trajectory of the K are higher-income knowledge workers, often able to work from home. On the downward part are lower-wage, lower-skilled workers in jobs that require close proximity to others. Government programs are likely to focus on those displaced workers. But past history suggests engaging and reskilling those workers could be a challenge. What’s more, many workers may be unable to move to centres or regions where new jobs may emerge. They’re more likely to opt for income-support programs.

6. Displaced workers need help transitioning to new jobs

What we’re seeing: Long-term unemployment—27 consecutive weeks or more—has surged by nearly 250% since the beginning of the pandemic. The spike is faster than we’ve seen in previous downturns, and is a natural consequence of sudden virus-containment measures. Government programs such as the Canada Emergency Relief Benefit may have reduced the pressure on many to return to work quickly, and there is still slack in the labour market. Long periods of joblessness can have multiple consequences, including eroding skills and increasing the likelihood that affected workers drop out of the labour force altogether.

What it means: Employment surged during the summer and early fall reopening. And while the end of the second wave should lead to another rise in employment, many jobs won’t be there waiting, because of permanent business closures and the dramatic shift in operating models in a range of sectors. Some affected workers may go back to school or retrain, but historically few laid-off workers have sought retraining. Moreover, low-skill workers are less likely to receive job-related training than high-skill workers.

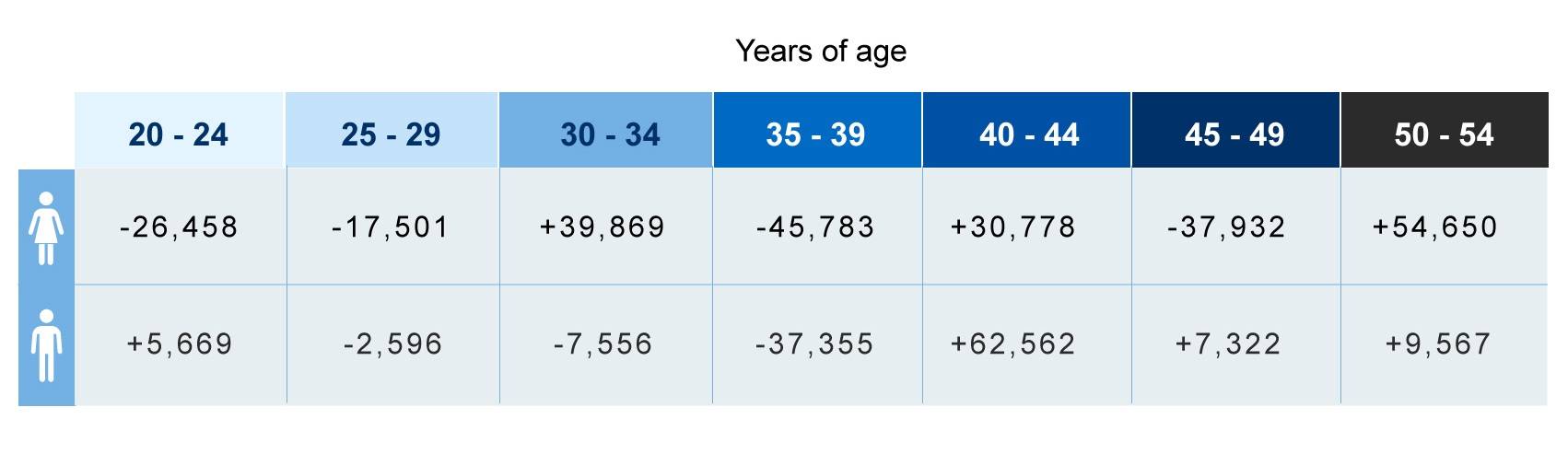

7. Most of the people exiting the labour force are women

Change in the size of the Canadian labour force since February, by age and sex, seasonally-adjusted

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

What we’re seeing: The pandemic knocked female participation in the labour force from a historic high to a three-decade low. While more than one million women have regained employment, two key cohorts (ages 20-24 and 35-39) continue to drop out. In the younger cohort, the majority are enrolling in post-secondary education and preparing to re-enter the workforce. But among women aged 35-39, many are leaving the labour force regardless of their education. The reason appears to be motherhood: women with children under 6 made up 41% of the labour force in February, but accounted for two-thirds of the ensuing exit from the labour force.

What it means: This trend is likely to persist until parents feel secure sending their children to school or daycare. We know women’s participation in the labour force has been a major boost to potential output and living standards, and is therefore key to the recovery. Recent federal commitments to a policy of universal, affordable childcare and early learning could support that shift. But it will require the active participation of provinces and flexibility from employers to help parents manage the new realities of work.

8. Canada’s immigration-fueled growth derailed

What we’re seeing: Virus fears and border closures brought immigration to an abrupt halt in the spring. The immigration system showed considerable resilience, maintaining the flow of temporary foreign workers in agriculture and allowing for accommodations for international students. But overall, 2020 sharply reduced both permanent and temporary immigration, one of the key drivers of Canadian population growth. In response, Ottawa dramatically increased targets for new permanent residents over the next three years to make up for the shortfall.

What it means: Canada is relying on newcomers—especially highly-skilled ones—to help drive the recovery, bolster domestic demand and maintain our working-age population. While increased targets will likely test the system’s capacity, further innovations will be needed to recruit and process potential immigrants in a world that is both more competitive for talent and still struggling to resume international mobility. Several sectors, particularly real estate and education, will depend on a positive transition.

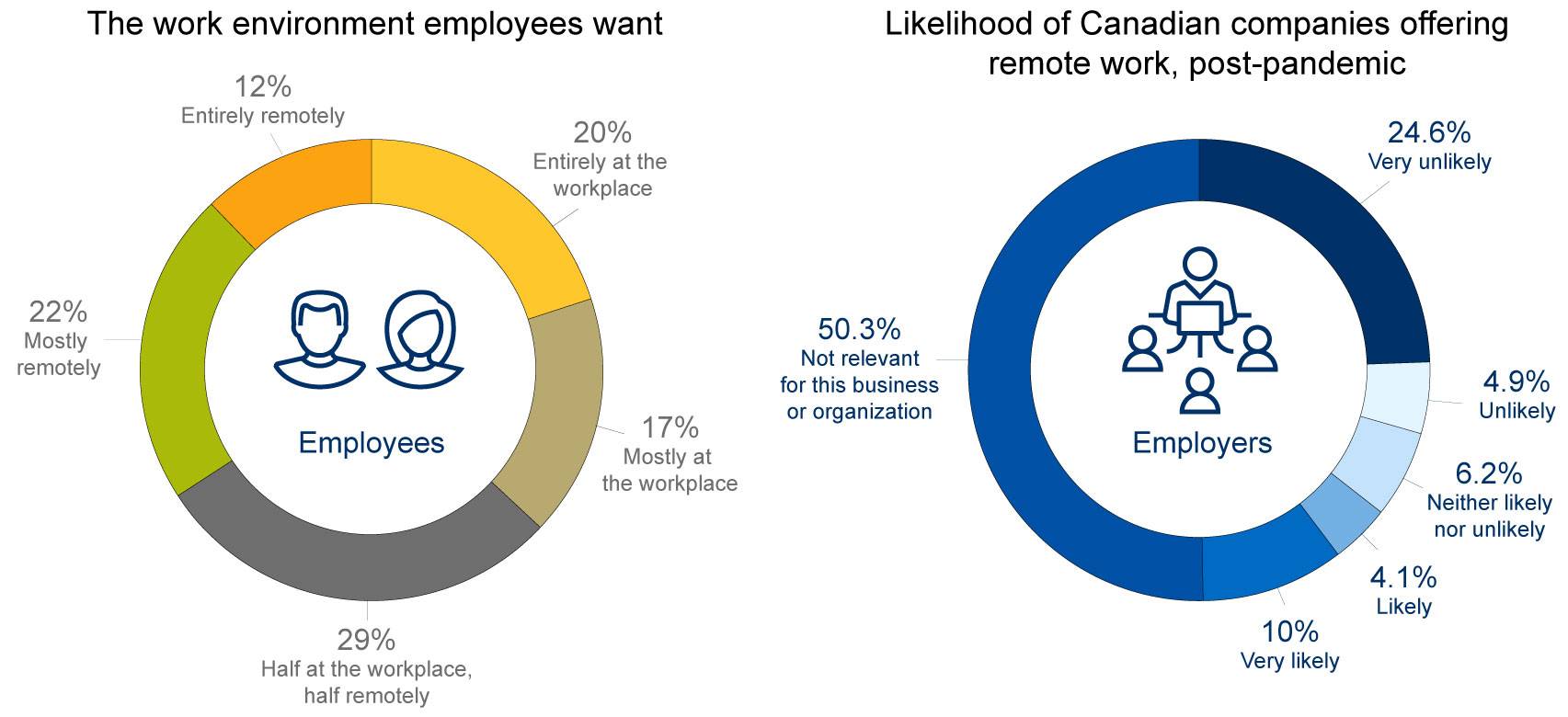

9. WFH or office? Employers and employees aren’t always aligned

Source: Statistics Canada, PwC, RBC Economics

What we’re seeing: The first lockdowns in the spring saw more than 5 million Canadians shift to remote work. By October, 2.4 million Canadians who don’t normally work from home continued to do so. Opinion surveys suggest most employees want at least some permanence of remote work arrangements. But so far, employers have been less enthusiastic. Among those organizations that can consider remote work arrangements, only about 30% are likely or very likely to do so post-pandemic.

What it means: The work-from-home model is here to stay, to some extent and for some workers. With so many employees demanding remote work, and experience showing that it often works well, companies will need to create flexible arrangements if they’re to compete in tight labour markets for highly skilled and mobile knowledge workers. While this flexibility will vary greatly across industries and workers, it will have implications for commercial and residential real estate and the design of our cities.

![]() We’re Living Differently and Spending Differently

We’re Living Differently and Spending Differently

10. Canadians are socking away cash

What we’re seeing: One of the least appreciated economic jolts of 2020 is that household savings have soared. Among the reasons: living and travel expenses fell, lenders extended credit deferrals, and many households didn’t lose their incomes. But another key factor was the federal government’s stimulus. By our estimate, in the second quarter, it injected $30 billion more relief into household accounts than was lost through the loss of income because of furloughs and job cuts. As government programs wind down and consumer savings dwindle, consumer spending will increasingly depend on employment gains. For that to happen, businesses will need to re-open and expand.

What it means: Canadians are sitting on a trove of unspent cash. By our count, household savings balances spiked a cumulative $160 billion relative to pre-COVID levels through the last three quarters. For consumers, a bigger cash buffer means a chance to spend on big-ticket items, invest and pay down debt. For businesses, the opportunity lies in finding ways to tap this spending power. But the availability of luxury and non-essential spending options, from travel to live performances, will also determine how quickly consumers deplete those savings.

11. E-commerce is now cemented in shopping habits

What we’re seeing: The proportion of goods and services we buy through e-commerce exploded amid the early lockdowns when consumers weren’t able to venture into stores. Even after reduced containment measures allowed more in-person shopping, e-commerce spending remained much higher than before the pandemic hit, suggesting a new habit had been hardwired.

What it means: It’s more important than ever for businesses, large and small, to up their game in a virtual marketplace. That will mean investments in new technologies and reskilling. The online economy can also create more opportunities for local producers to reach global markets. But it will require regions and sectors to consider their place on technology platforms like Amazon or Facebook in which consumer preferences can be shaped by the platform, and the economic pie is divided much differently.

12. Nesting nation: consumers mix it up

What we’re seeing: The pandemic changed not just where we buy but what we buy. With homes now doing double duty as workplaces, Canadians have renovated, remodeled and re-landscaped rather than focus on their wardrobes. Summer also saw a surge in spending on sports and fitness equipment, backyard toys and recreation vehicles. Winter may bring an equal shift in spending to anything that keeps savings-rich consumers active, comfortable and warm.

What it means: Some businesses have already adapted, with clothing stores offering fittings online and gyms moving to virtual fitness classes. Others have shifted to curbside pick-up models to ensure customers get the products they need, when they’re needed. Demand for some hard-hit items could return as a vaccine becomes available. The likelihood of more work-from-home days, for example, will mean lower gasoline demand and higher spending on groceries even after employees go back to their formal workplaces.

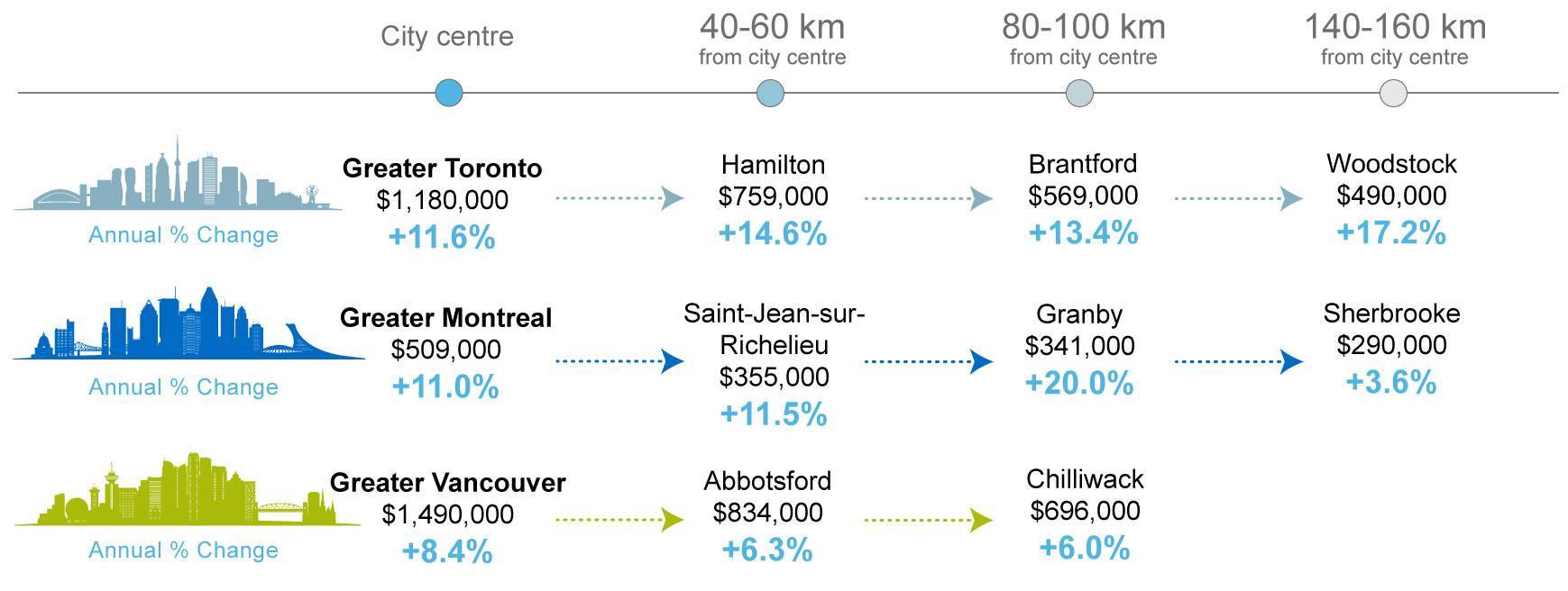

13. So long, big-city life: remote work loosens ties to pricey markets

Price of a single-family home, Oct/20

Source: RPS, RBC Economics

What we’re seeing: No longer tied to offices, city dwellers are hearing the call of bigger yards and larger living spaces. That’s driven up prices in smaller communities and for larger detached homes. It’s also increased rental options and lowered rents in cities. An ongoing blend of remote and office work could see the appetite for more space continue.

What it means: Work-from-home won’t be a silver bullet for Canada’s affordability issues. Even a small fraction of Canadians opting to move big-city incomes to more distant locales could overwhelm smaller communities and make affordability more challenging for local residents whose incomes are lower. Softer condo prices in big cities are a plus for younger or first-time homebuyers, including newcomers. Higher prices for single-family homes are a negative for these buyers, but are giving a wealth boost to existing homeowners.

![]() Helping Businesses Embrace A Virtual Destiny

Helping Businesses Embrace A Virtual Destiny

14. Canadian businesses lean hard on support from Ottawa

What we’re seeing: The federal government has offered a range of programs to help sustain businesses through the crisis. While several programs initially saw a slow uptake, they were made more generous, responsive and accessible—and have seen improved demand. The November 2020 Fall Economic Statement extended wage and rent subsidies along with more small business support, and added new credit facilities for hard-hit sectors.

What it means: Many businesses rely heavily on these lifelines, but they also rely greatly on the decisions of local health authorities, and provinces, in determining which sectors and types of businesses can operate. Some won’t have the liquidity, balance sheet or patience to ride it out. Moreover, some may need to adapt to a new economic landscape, with changes in what and where consumers buy. Business bankruptcies have remained stable overall—although they’ve increased in some sectors like arts and entertainment and retail—and will be watched carefully going forward.

15. For bricks-and-mortar retailers, a virtual second act

What we’re seeing: Rather than signaling a death knell for traditional retailers, the COVID crisis has, for some, helped catalyze transformation. More than half of the persistent growth in e-commerce sales since April was driven by bricks-and-mortar retailers adapting to the virtual marketplace. Some of these gains were driven by e-commerce, which Canadians had been slower than many other countries to adopt before the crisis. But they were also fueled by a jump in curbside pickup, as consumers looked to get out of the home and speed up delivery.

What it means: The demand for e-commerce is still there if retailers can embrace the transition to digital sales channels, and pivot their efforts to help build better platforms for consumers scrolling online. The pressure for hybrid models, to compete with both digital platforms and big-box retailers, will also grow. Smaller retailers, already under enormous strain, and often lacking the necessary capital, could struggle to make the leap. Policymakers will need to find ways to encourage their transition.

16. Cashless is king

What we’re seeing: A major shift to cashless and contactless commerce, initially sparked by the spring lockdowns, has held steady. Cash use has dropped from about 10% of payments to about 8% of payments, continuing a long-running trend. E-transfers have grown from 10% to 12%, picking up most of the decline. Canadians are also tapping their cards more. After briefly returning to in-person payments, remote payments started to rise as growing case counts triggered second lockdowns in some parts of the country.

What it means: As Canadians embrace the ability to work and study anywhere, businesses will have to meet them where they are—often virtually. With less cash changing hands, more businesses will need to enable digital transactions. Accepting app-based payments, and other alternative forms of payment may become imperative, even for firms still physically interacting with customers, as they face pressure to reduce contact at the point of transaction.

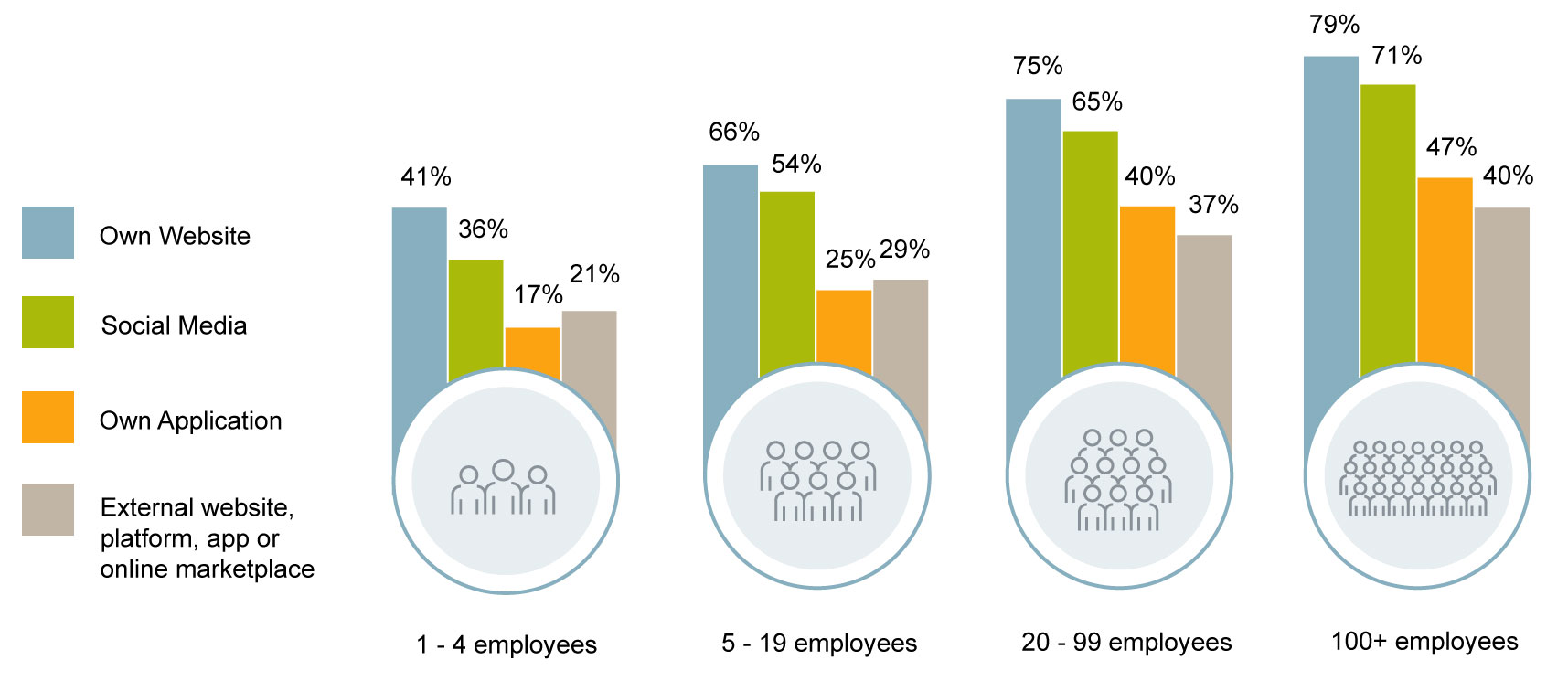

17. Many small businesses still lack an online presence

Share of firms using various methods to provide goods or services to customers or users, mid-Sept to mid-Oct, 2020

Source:Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

What we’re seeing: Small businesses are the backbone of Canada’s economy, representing 42% of GDP and 48% of new jobs. Yet small businesses in particular have been caught off guard by the abrupt transition to a virtual economy. Many still lack even a business website, with some citing barriers such as lack of technical expertise or high startup and maintenance costs.

What it means: This crisis could be the moment that these small firms make the jump, repositioning themselves for a post-pandemic economy more virtual and mobile than we’ve seen. But many can’t do it alone. Programs like Digital Main Street are helping small businesses connect with digital service providers. Tax credits for small firms to invest in Canadian-designed software and hardware would encourage tech adoption. And local business organizations and chambers of commerce can play a role in helping their members adopt digital tools.

18. Investors reward IP-rich firms

What we’re seeing: U.S. equity markets hit record highs toward the end of 2020. Tech companies with intangible capital— including intellectual property like software, patents and data-led the rebound as investors bet the pandemic would accelerate the adoption of e-commerce, cloud computing and other technologies. It’s been a trend for the past quarter-century, as investors placed more value on intangible assets like IP. But Canada has been slower to adjust, with the value of such intangibles to corporate Canada remaining largely flat over the past decade.

What it means: Business investment involves more than plants and equipment—intangible investment in research and development and software is an increasingly important component of capital spending. Some 70% of the TSX Composite’s market value derives from intangibles, compared with more than 90% of the S&P 500’s value. Developing intellectual property in Canada, and keeping it here, is key to building more valuable companies in the industries that are thriving in a more digital and decentralized economy.

For more on how business leaders from across the country are pivoting and what the “new normal” will look like, listen to our Disruptors podcast episode.

Pandemics, Pivots, and Predictions

![]() A Map for Policymakers

A Map for Policymakers

19. Low rates help a heavy-spending Ottawa…for now

What we’re seeing: Canada’s crisis aid pushed the federal deficit as a share of the economy beyond those of our G20 peers. November’s Fall Economic Statement indicated there’s little chance this will slow, with deficits that could be over $100 billion for the next few years. Overall, that’s brought the federal debt to more than $1 trillion, and thus far there’s been little clarity from Ottawa on how it plans to tackle that enormous sum.

What it means: Amid a still-cloudy outlook, substantial fiscal support remains in place with a tilt emerging to the harder-hit industries that could face lasting damage. Pending stimulus spending should focus on initiatives that lift long-term economic growth. Policies will need to enable a new generation of technology-driven innovation and provide a path for displaced workers back into the labour market. Support for childcare will enable more people to join the labour market, while the extension of some business-focused support programs will lift employment and support consumer spending. Infrastructure spending should focus less on the hard and more on the soft and smart spend to enable the economy to adjust to the structural changes at play. Low-interest rates will keep debt charges manageable for the near term but economic growth is the only sustainable solution to getting our fiscal house in order.

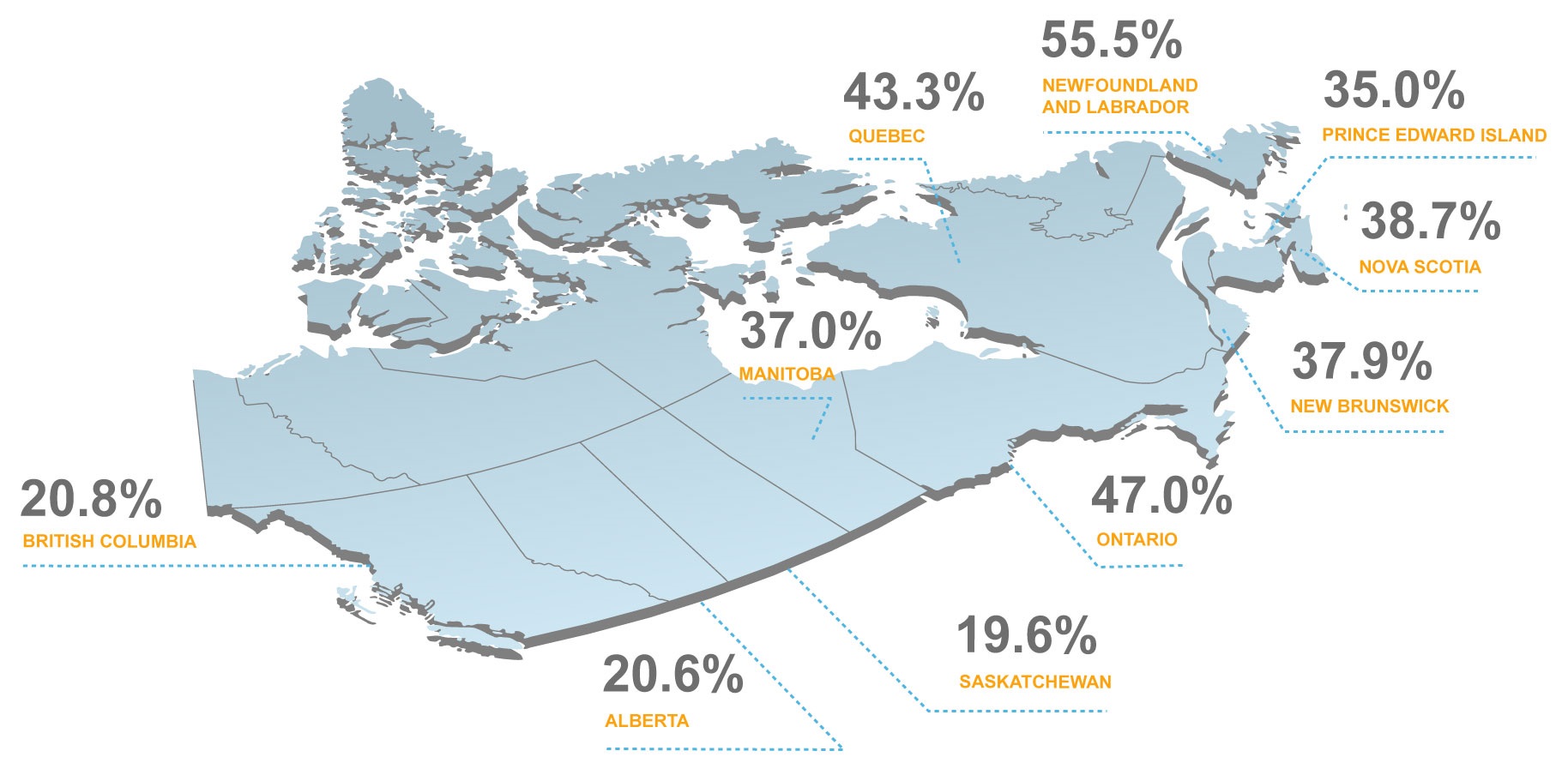

20. Healthcare costs worsen provincial cash crunch

Net provincial debt to GDP, FY20/21, percent

Source: RBC Economics

What we’re seeing: Provinces were already carrying debt-to-GDP ratios at levels not seen since the 1990s. The pandemic added ballooning healthcare costs to their burdens. 2020 will be a high-water mark in terms of deficits across provinces. The most challenged are the ones that are most dependent on oil and gas revenue, especially Newfoundland and Labrador. The rapidly aging populations of eastern Canada have added to the strain, with more healthcare costs and less tax revenue.

What it means: Even with temporary emergency healthcare expenditures coming off, it will take years to put provincial finances back on a sustainable path. Provinces in relatively stronger financial shape pre-COVID should regain breathing room first, though provinces running larger deficits and carrying heavier debt loads before the pandemic will face greater challenges. Pressure will remain on Ottawa to increase health transfers to the provinces, and add support in other areas of social spending, notably daycare and housing.

21. A borrower’s opportunity, a saver’s dilemma

What we’re seeing: The Bank of Canada slashed its key interest rate and adopted unconventional policies like forward guidance (committing to keep the policy rate at its current level until the economy recovers) and quantitative easing (buying government bonds). The unconventional tools are designed to lower longer-term interest rates across the yield curve, reducing borrowing costs on fixed-rate mortgages and longer-term business loans. That’s helped home sales recover sharply, but business investment remains subdued. Savers, meanwhile, will have to look beyond safe, fixed-income investments to grow their money.

What it means: Central banks are providing ample stimulus in an attempt to offset the pandemic’s disinflationary impact. Investors are betting policymakers will be successful in re-inflating the economy, with market-based inflation expectations in Canada and the U.S. rising back to pre-pandemic levels or higher, reflected in a steepening yield curve. But there appears to be little concern that easy monetary policy will overstimulate the economy and result in excessive inflation. Subdued inflation pressures reflect constrained activity, particularly in the services sector, which has been the source of consumer price inflation in recent years. Although consumer prices are likely to remain moderate, asset-price inflation can be expected to continue as we move through the recovery.

Download the Report

Contributors:

John Stackhouse, Senior Vice President

Craig Wright, Senior Vice President, Chief Economist

Dawn Desjardins, Vice President, Deputy Chief Economist

Carolyn King, Senior Managing Editor

Cynthia Leach, Senior Director, Economic Thought Leadership

Naomi Powell, Economics Editor

Andrew Agopsowicz, Senior Economist

Rannella Billy-Ochieng’, Economist

Darren Chow, Senior Manager, Digital Media

Trinh Theresa Do, Senior Manager, Thought Leadership Strategy

Claire Fan, Economist

Carrie Freestone, Economist

Colin Guldimann, Economist

Robert Hogue, Senior Economist

Nathan Janzen, Senior Economist

Josh Nye, Senior Economist

Farhad Panahov, Research Associate

Andrew Schrumm, Senior Manager, Research, Thought Leadership

Samantha Simunyu, Manager, Publishing

RBC Economics provides RBC and its clients with timely economic forecasts and analysis.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More