- Canada’s ability to help alleviate a global food crisis through increased food exports is limited.

- Constraints on the conversion of land for farming makes expanding production of crops affected by the Ukraine war unlikely in the short-term.

- But as a global fertilizer powerhouse, Canada can help sustain crop yields in other countries.

- Canada can increase potash fertilizer production in the near term, but expanding nitrogen fertilizer production will require more time and investment.

- The bottom line: boosting fertilizer production is one way Canada can make a difference—but it will demand a careful consideration of the impact on costs and emissions.

Canada can’t easily bridge gaps in global food supplies

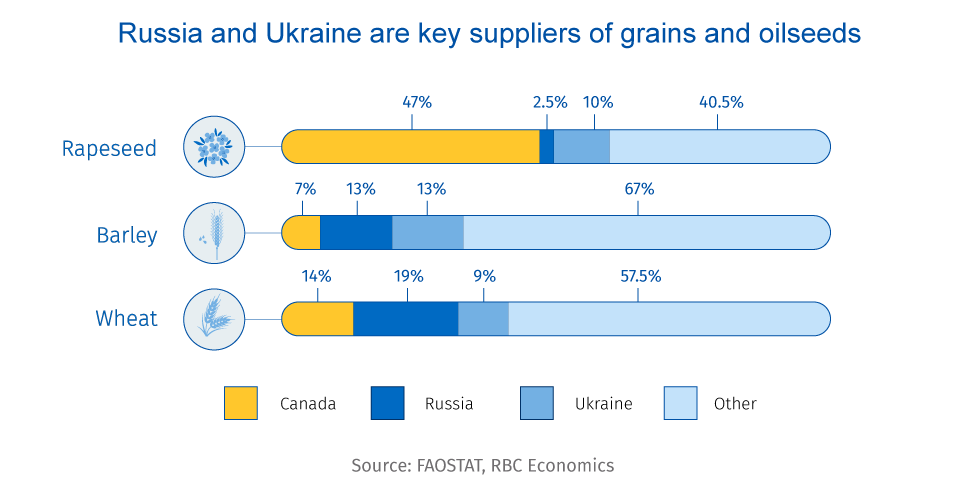

The war in Ukraine, the pandemic and the energy shock have thrown the global food system into disarray. It’s also pushed countries in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa to the edge of a food crisis. Ukraine and Russia are key suppliers of grains and oilseeds, with their harvests contributing roughly 12% of the calories traded globally. But many of Russia’s exports have been disrupted by the war while an estimated 20 million tonnes of grain (the equivalent of 2.54% of annual global wheat consumption) remain trapped in warehouses in Ukraine.

Can Canada produce more food to fill the gap? Not in the near term. Canada is the world’s fifth largest exporter of agricultural goods and the fourth largest exporter of wheat, behind Russia, the European Union and the U.S. Cropland is already seeded for this year’s growing season, with Canadian farmers indicating their intention to plant 7.2% more wheat. But despite Canada’s large size, vast portions of additional land cannot be converted to agricultural production due to barriers related to climate and terrain. And expanding farms involves costly undertakings to prepare the land, acquire new supplies, and install irrigation systems. In the future, increasing productivity will largely depend on more efficient techniques and agricultural technologies.

But Canada is a global leader in fertilizer production

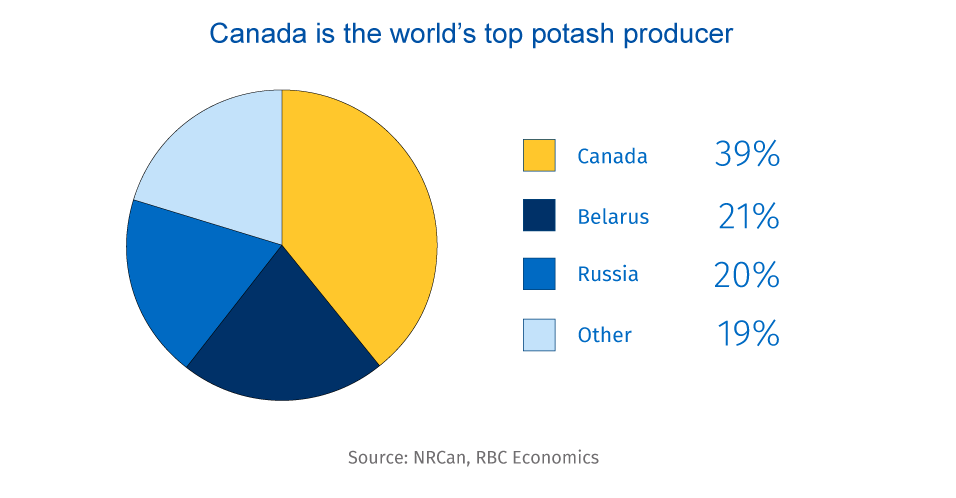

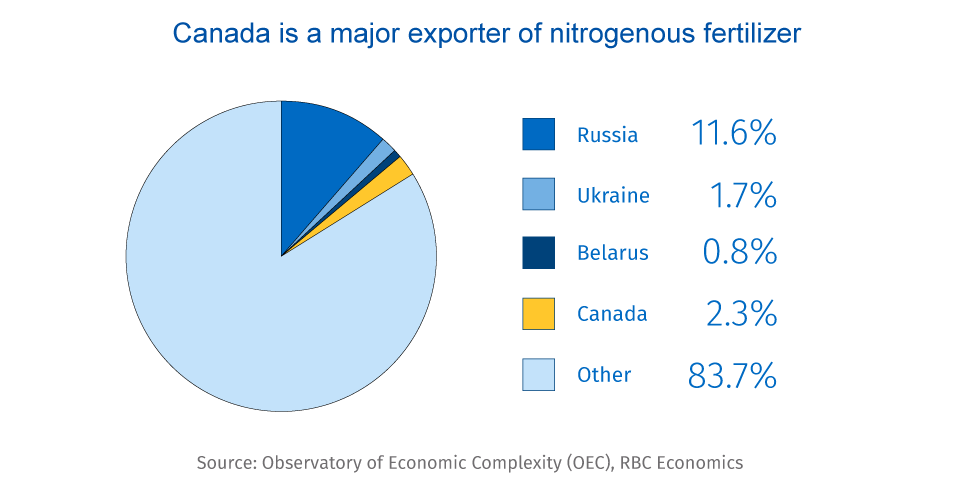

What Canada can do is help ensure the situation isn’t made worse—by filling another critical gap. Canada is a top player in the global fertilizer market. It’s the world’s largest producer of potash—a type of potassium fertilizer—and the 14th largest exporter of nitrogen fertilizers.

Around the world, the availability of these key inputs is increasingly under threat. Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus account for nearly 15% of global nitrogenous fertilizer exports. The combined impact of the war and sanctions levied against both Russia and Belarus has cut off much of that supply. And amid rising scarcity, other major supplier countries, including China, have imposed export restrictions on fertilizer to protect domestic production. In all, roughly 20% of nitrogen and potash fertilizer exports have been disrupted.

Canada’s fertilizer industry still has room to grow and could play an important role in alleviating that global shortage. What’s more, 85 to 90% of Eastern Canada’s nitrogen fertilizer comes from Russia. This suggests an opportunity to increase self-sufficiency in this region (though it would require major upgrades to transport infrastructure to move supplies from Western Canada.)

Boosting some production will require investment

Still, there’s a delicate balance to be struck in maintaining agricultural productivity, increasing fertilizer production, and achieving Canada’s Net Zero ambitions. Major domestic and international fertilizer producers have made investment commitments in Saskatchewan, with the aim of increasing production in the near-term and expanding capacity and efficiency in the longer term.

But ramping up production of nitrogenous fertilizers is more difficult. Canadian nitrogen facilities are running at full capacity. And while expanding potash production doesn’t necessarily require new facilities, the investment needed to increase production of nitrogenous fertilizers would be significant. It requires the construction of new manufacturing plants, which could take a year or more to complete.

And all of this comes at a time when the federal government is aiming to cut 30% of emissions from chemical fertilizer use by 2030, and move producers more quickly toward Net Zero. Canada has the ability to expand its role as an outsized player in the global fertilizer market, but it will require a coordinated evaluation of the impacts—and significant effort from government, farmers, and other stakeholders.

Ben Richardson is responsible for researching pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, he obtained a Master’s degree from the University of Toronto and worked in Washington, D.C., at the Woodrow Wilson Center, researching topics concerning Canada-US relations.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

Benjamin is responsible for researching pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, he obtained a Master’s degree from the University of Toronto and worked in Washington, D.C., at the Woodrow Wilson Center, researching topics concerning Canada-US relations.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More