- Indigenous Peoples1 account for 5% of Canada’s population and 2.5% of pre-pandemic GDP

- But Canada’s Indigenous population has significantly worse labour market outcomes than Non-Indigenous Canadians with lower participation rates, higher unemployment rates, and an 8% hourly wage gap (among adults ages 25 to 54).

- A wide infrastructure gap (sized at $350 billion by the Assembly of First Nations) is part of the problem. Indigenous Peoples are significantly more likely to be underhoused and the majority living on reserve have limited access to high-speed internet.

- The bottom line: Closing the Indigenous infrastructure gap could help boost annual Indigenous output by up to 17%, raising both employment levels, productivity, and wages earned. The potential benefits extend beyond the Indigenous population, adding close to half a percent to the total production capacity of the Canadian economy.

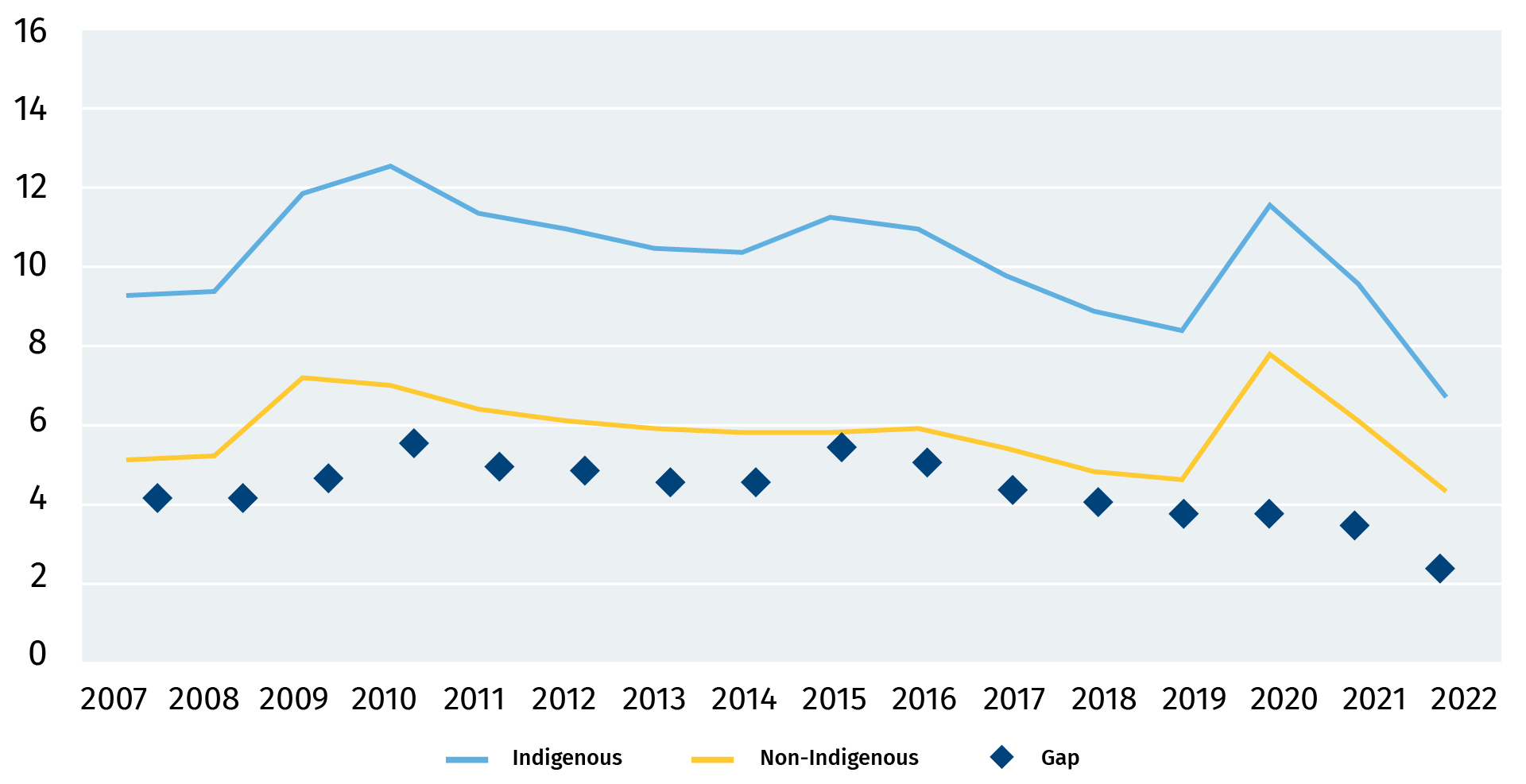

Stubborn employment gap between Indigenous & non-Indigenous population persists

Unemployment rate, %, prime age population; off-reserve

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

Canada’s Indigenous populations grapple with a huge infrastructure gap

It is well-known that Canada is one of the most educated countries in the world, with the second highest share of adults aged 25 to 34 with tertiary education in the OECD. But as one of the wealthiest countries globally, Canada has done little to address the widening Indigenous infrastructure gap which jeopardizes the economic outcomes of 5% of Canada’s population.

Canada’s Indigenous populations are more likely to live in remote regions. In the face of high costs for essentials alongside logistical challenges and poor infrastructure, Indigenous communities face limited access to building materials. This has resulted in one in six Indigenous Peoples living in homes in need of immediate repair. And Indigenous Peoples are twice as likely to live in overcrowded housing arrangements as non-Indigenous populations. An additional barrier for those who live on-reserve and in remote communities is access to highspeed internet. This infrastructure gap limits access to educational and economic opportunities present in more connected communities. The Assembly of First Nations estimates that Canada needs to spend $350 billion to close the gap by 2030.

Canada’s investment in closing the infrastructure gap will boost productivity and wages, providing significant lift to Indigenous output in Canada. Access to improved infrastructure will enhance educational outcomes, closing gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous labour market participation, employment, and earnings.

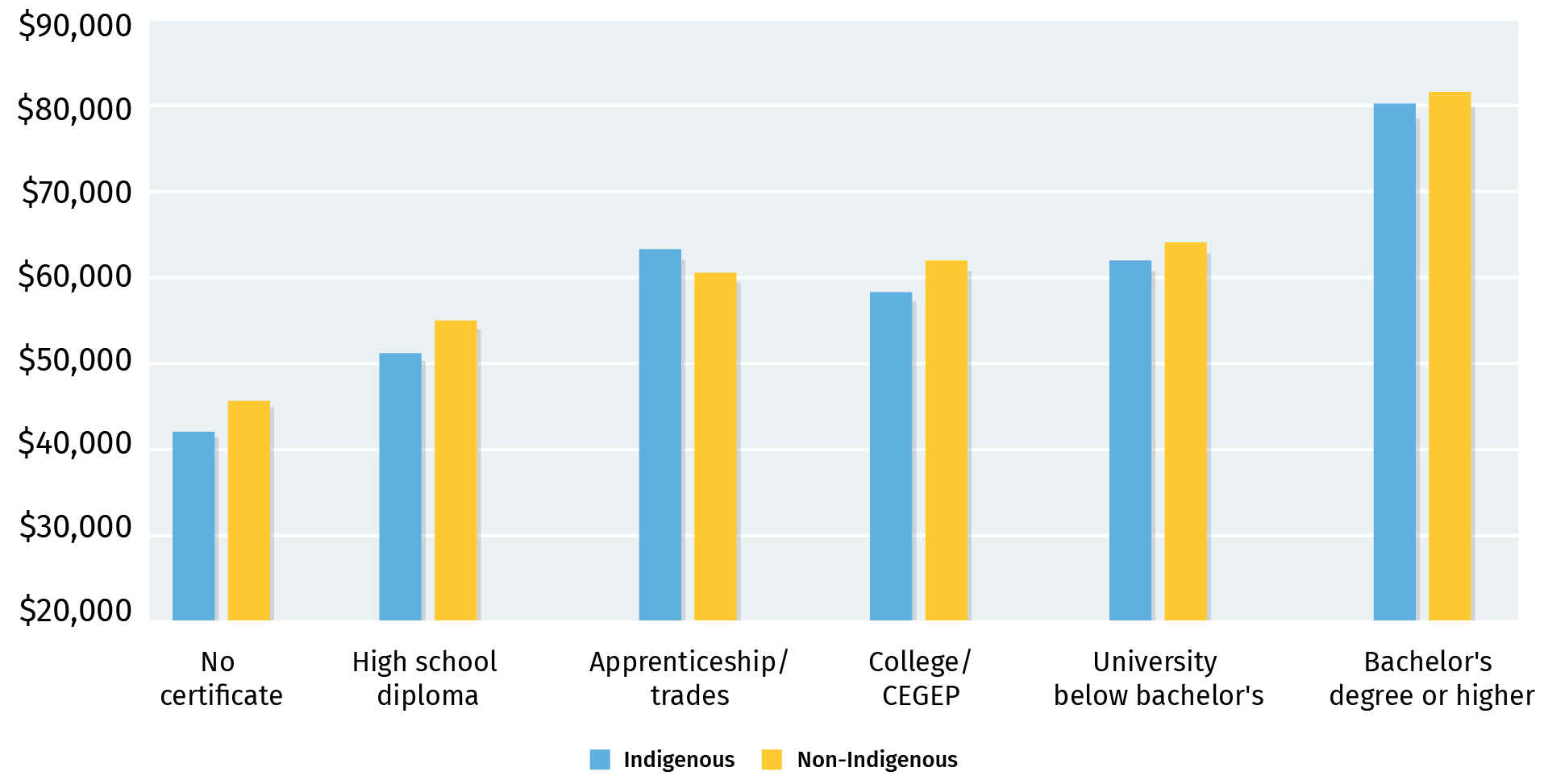

Indigenous income gaps widest for those without post-secondary

Median 2021 employment income, ages 25-54 who worked full-time, full-year

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

The infrastructure gap leads to worse Indigenous labour market outcomes

Canada’s Indigenous population is younger and works longer hours than their non-Indigenous counterparts but a pernicious wage gape persists. Working-age Indigenous employees earned 92 cents in average hourly wages for every dollar earned by the non-Indigenous population in 2022.

What’s driving the wage gap? Education plays a role. And in fact, the wage gap is more pronounced among those with lower levels of educational attainment. Indigenous Peoples without a high school diploma had a median income that was 8% lower than the non-Indigenous population in 2021. When looking at those with at least a bachelor’s degree, the gap closes to 1%. Currently, however, there is also a gap between the Indigenous and non-Indigenous population when it comes to obtaining post-secondary degrees, with the Indigenous population almost three times less likely to hold a university degree. Overall, the Indigenous population is three times as likely to have no formal education compared to the non-Indigenous population.

Bridging the employment gap could boost Indigenous output by up to 17%

Supporting and improving educational outcomes for Canada’s Indigenous population will likely improve participation and unemployment rates as well. While Indigenous Peoples make up 5% of the population, the Indigenous economy accounted for 2.5% of Canadian output ahead of the pandemic. There remains nearly a six percentage-point gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous working-age (25-54) participation rates. The Indigenous population has grappled with a historically elevated unemployment rate that has proven quite sticky.

Living in remote areas was a significant factor for Indigenous Peoples facing unemployment. Over 17% of the Indigenous working-age population did not participate in the labour force in 2022 compared to 11% of the non-Indigenous population. This is a concern, as 40% of the Indigenous population falls under the age of 24, compared to only one-quarter of the non-Indigenous population.

As the Canadian population ages and labour shortages become more acute, with the right infrastructure in place, Indigenous youth are well-positioned to fill these gaps as demographics shift. Boosting Indigenous participation rates and employment rates to current non-Indigenous rates would not only boost Indigenous output by up to 17% (including higher employment and wages) but would add half a percent to the productive potential of the Canadian economy annually

1Indigenous Peoples is a collective term used for the original peoples of North America, here it refers to individuals who self-identify as one of 3 recognized groups within Canada: First Nations, Inuit, and Metis.

Carrie Freestone is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group and is responsible for monitoring key indicators focusing on consumer spending and household debt as well as labour markets, GDP, and inflation. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from Queen’s University and a Master of Arts in Economics from the University of Ottawa.

Farhad Panahov is an economist RBC. He studies the labour market – largely focusing on the future of work, demographic change, diversity, and human capital. He holds a BSc in Economics from the University of British Columbia, and Master of Applied Science in Data, Economics, and Development Policy from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More