- Supply chain pressures are finally easing as consumer demand slows.

- This, together with flagging commodity prices, has cooled inflation in Canada.

- The squeeze is unlikely to return. But for some retailers, the abrupt reversal in supply has created inventory gluts that may prompt further price reductions.

- The bottom line: Ongoing moderations won’t end inflation. But as central banks press on with rate hikes, diminishing real spending power will ultimately drive inflation back to target.

Global supply chain bottlenecks have started to clear

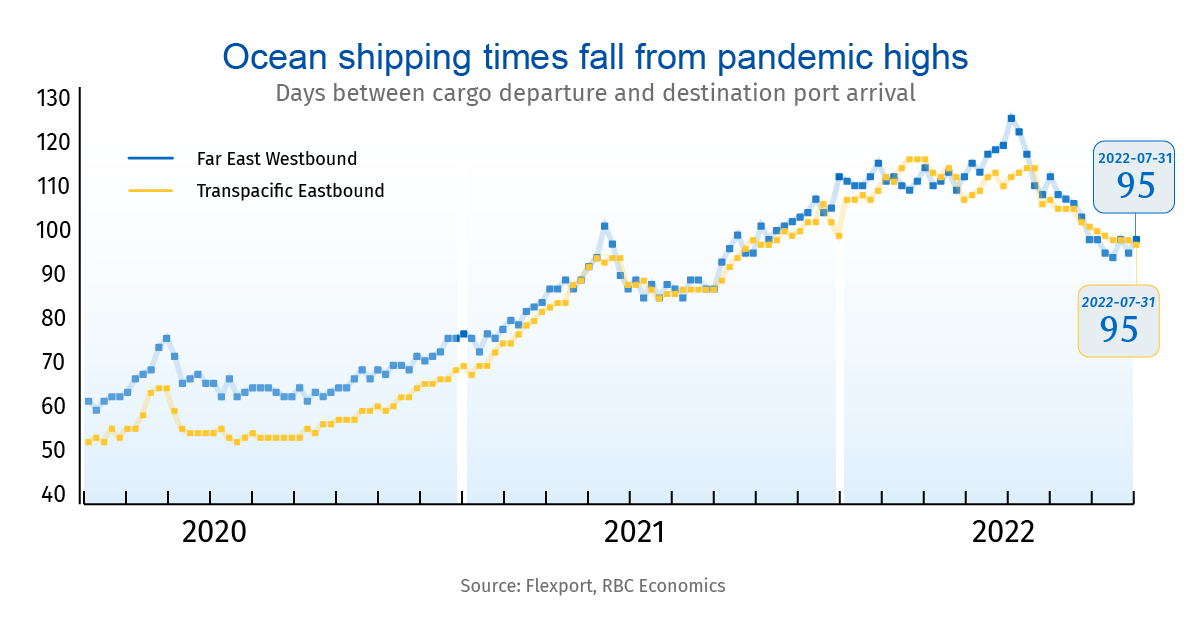

It’s been a story of extremes for global supply chains—and for inflation. Unprecedented supply line disruptions that drove the initial surge in prices during the pandemic are finally easing. And ocean shipping times (while still longer than normal) are a lot closer to what they were in early 2021 for the key routes of Asia to North America and Asia to Europe.

Will these supply chain snarls return? We think it’s unlikely given the expected slowdown in consumer spending. Auto remains one sector where tension might last longer, given the sheer amount of backlogs that may be too large to clear quickly. And rolling lockdowns in China are still a key risk.

But those uncertainties have not been enough to derail improvements in supply chains. And further easing is likely as central banks hike interest rates, cutting further into household purchasing power and pushing down demand for both physical merchandise and service activities. We expect the Bank of Canada to increase the overnight rate by another percentage point to 3.5% by October with other global central banks—including the U.S. Fed—also continuing to hike interest rates aggressively. That means both global supply chain pressures and inflation will continue to ease going forward. But it also means moderate recessions in both the U.S. and Canada are likely in the year ahead.

Inventory shortages become gluts, pushing prices down

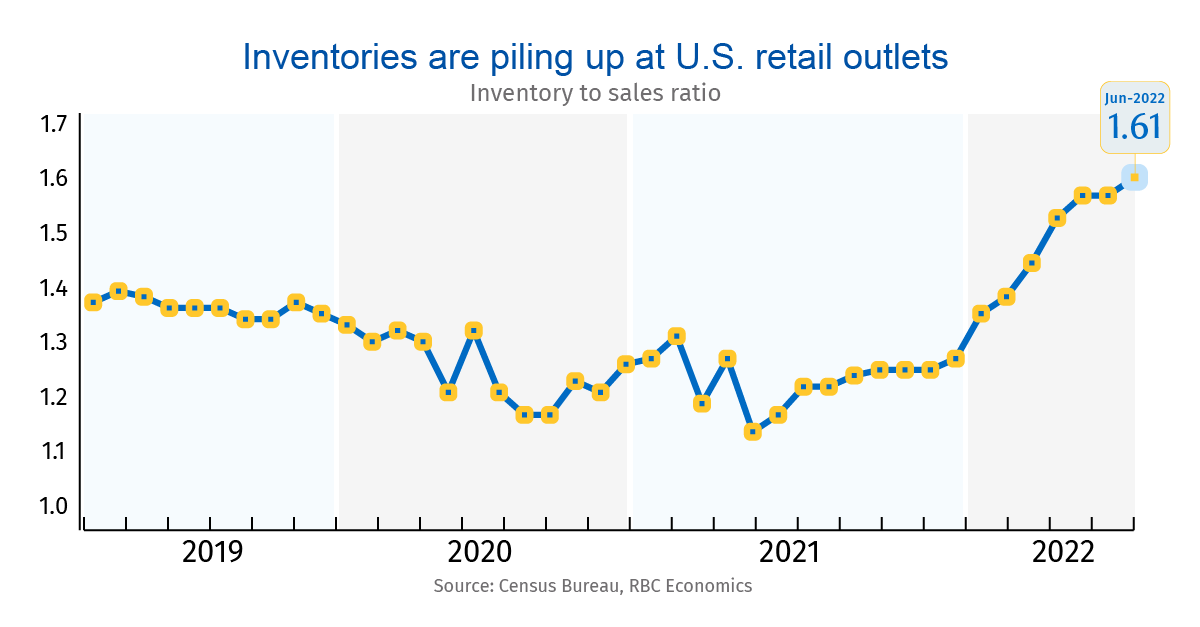

With fewer services available, the early days of the pandemic were marked by a surge in purchases of physical goods—think Peletons, home accessories and patio furniture, instead of vacations and meals in restaurants. Global supply networks buckled under the pressure. As vessels lined up outside ports, shipping delays rose to record levels and costs soared. In response, businesses moved away from “just-in-time” inventory management—in which raw material orders are aligned with production and sales schedules to increase efficiency or reduce the cost of holding inventory. Rather than risk bare shelves or a shortage of materials, firms began ordering stocks much farther ahead of time.

That trend is now reversing. Ports are no longer heaving with backlogs and cargo is moving more smoothly through the system. But spending is slowing just as those shiploads of electronics, clothing and other goods arrive. As a result, for some businesses, the struggle to meet demand has turned into an inventory glut. In June, the U.S. ratio of inventory-to-sales at general merchandise stores rose to its highest level since March 2006. That’s raising the prospect that, faced with bloated inventories, some retailers will need to cut prices.

But more interest rate hikes are still needed to rein in inflation

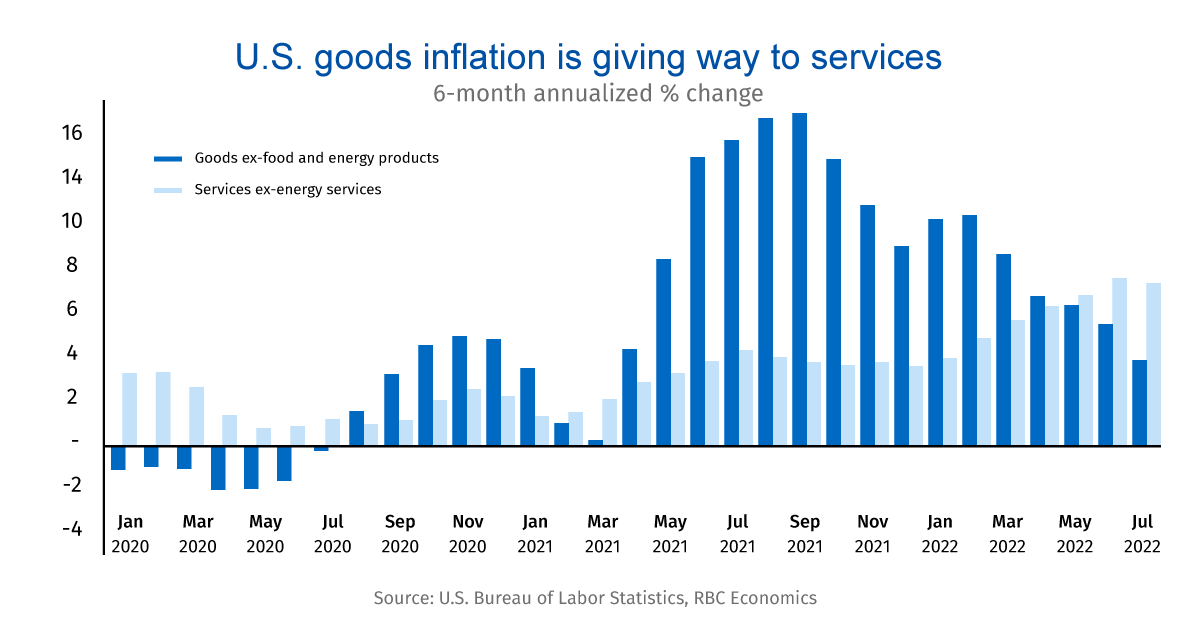

While painful for retailers, there is a silver lining. These price cuts will lower inflation that’s already cooling due to falling global commodity prices. To be clear, prices have continued to increase compared to levels a year ago, but for merchandise, prices are rising at a much slower pace. Growth in prices for U.S. goods (excluding food and energy products) fell to just under 4% at an annualized rate over the last 6 months. While that rate is still too high, it’s down significantly from its 15% peak in September last year.

But if goods demand has waned somewhat, services spending has taken off. With many pandemic restrictions removed, Canadians are rushing to spend on travel and in the hospitality sector. That’s a problem for central banks trying to get broader inflation trends under control, given how much service consumption accounts for in Canadian GDP (almost 30%).

Despite evidence global inflation pressures may have finally peaked, it will take more than easing supply chain conditions to bring price growth fully back to target. Indeed, we expect headline inflation in Canada to end the year at a still-elevated 6.2%, buoyed by higher demand for travel and leisure services. Recent developments have been positive—year-over-year CPI growth edged lower for the first time in a year in July on lower gasoline prices. And we expect inflation to ease closer to central bank target rates by the end of 2023. But we don’t expect that to happen without higher interest rates and a further slowing in consumer demand.

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group”. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic trends and is responsible for projecting key indicators on GDP, labour markets as well as inflation for both Canada and the US.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More