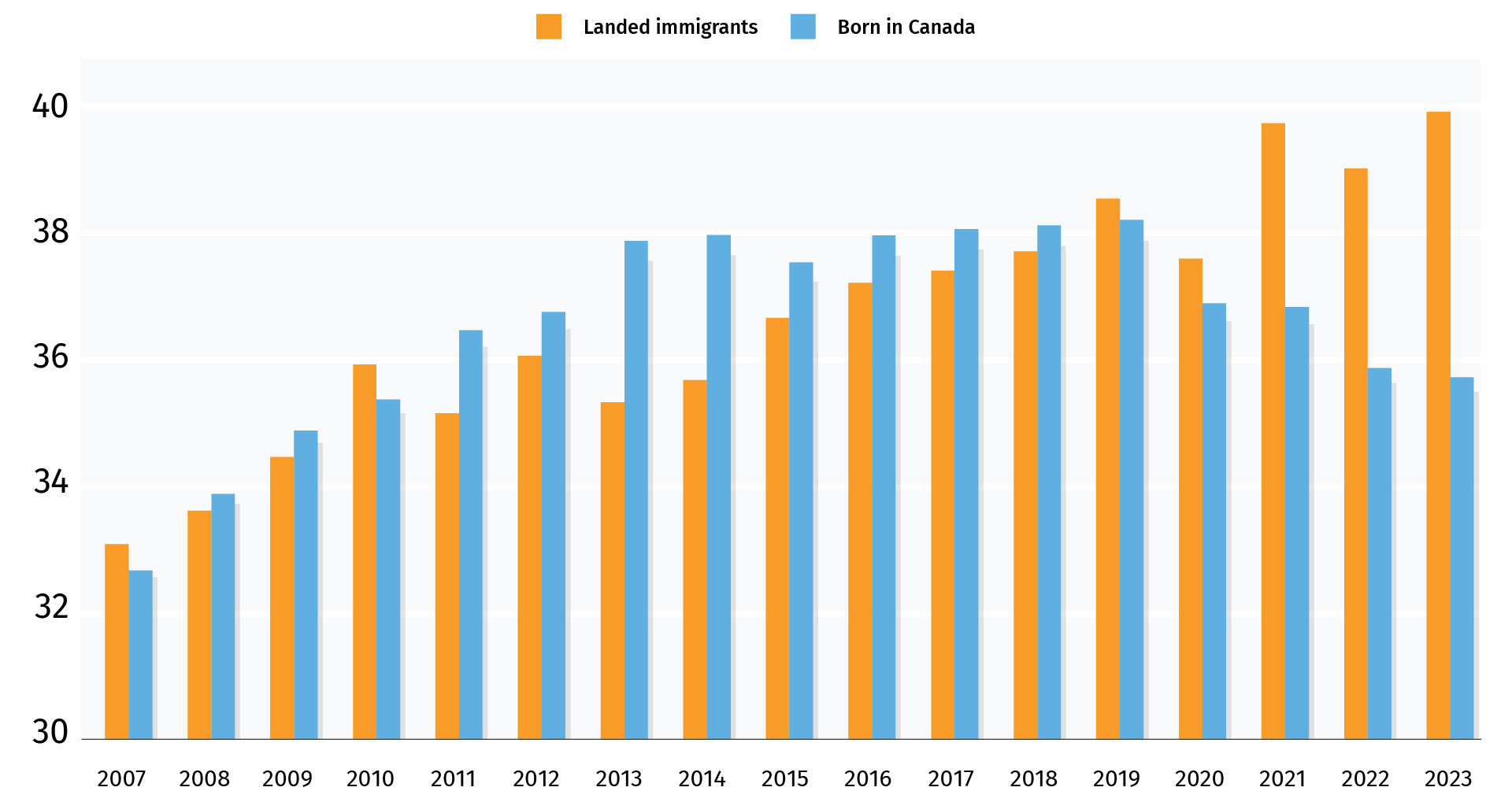

- Immigrants are outperforming their Canadian-born peers when it comes to labour force participation. That’s especially true for immigrant workers aged 55 and above, who have increasingly chosen to keep working and retire later.

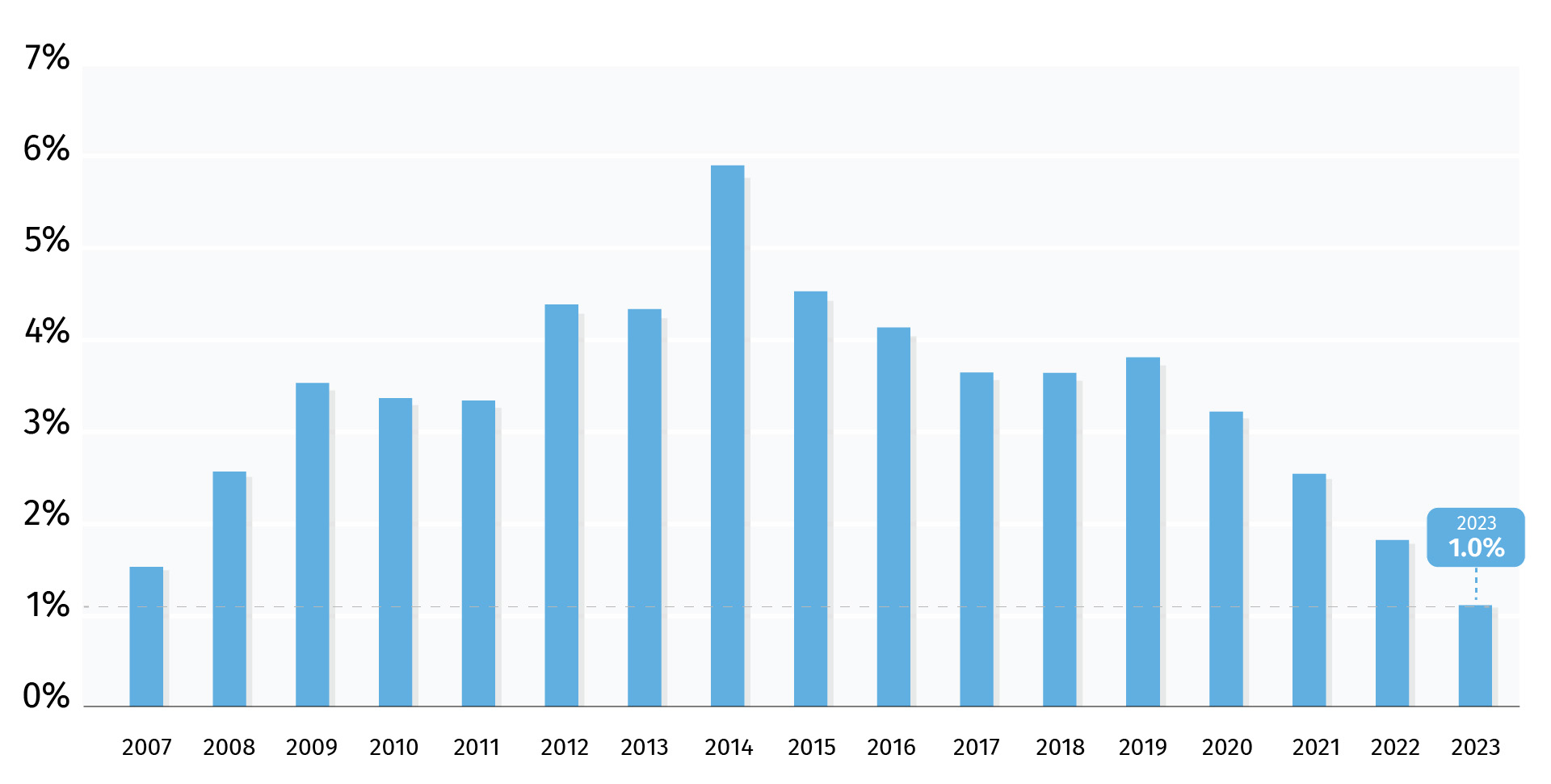

- Longer career spans among immigrant workers also came with better economic outcomes. The gap in wages between immigrant and Canadian-born workers has been narrowing since the mid-2010s and is at its lowest level in two decades.

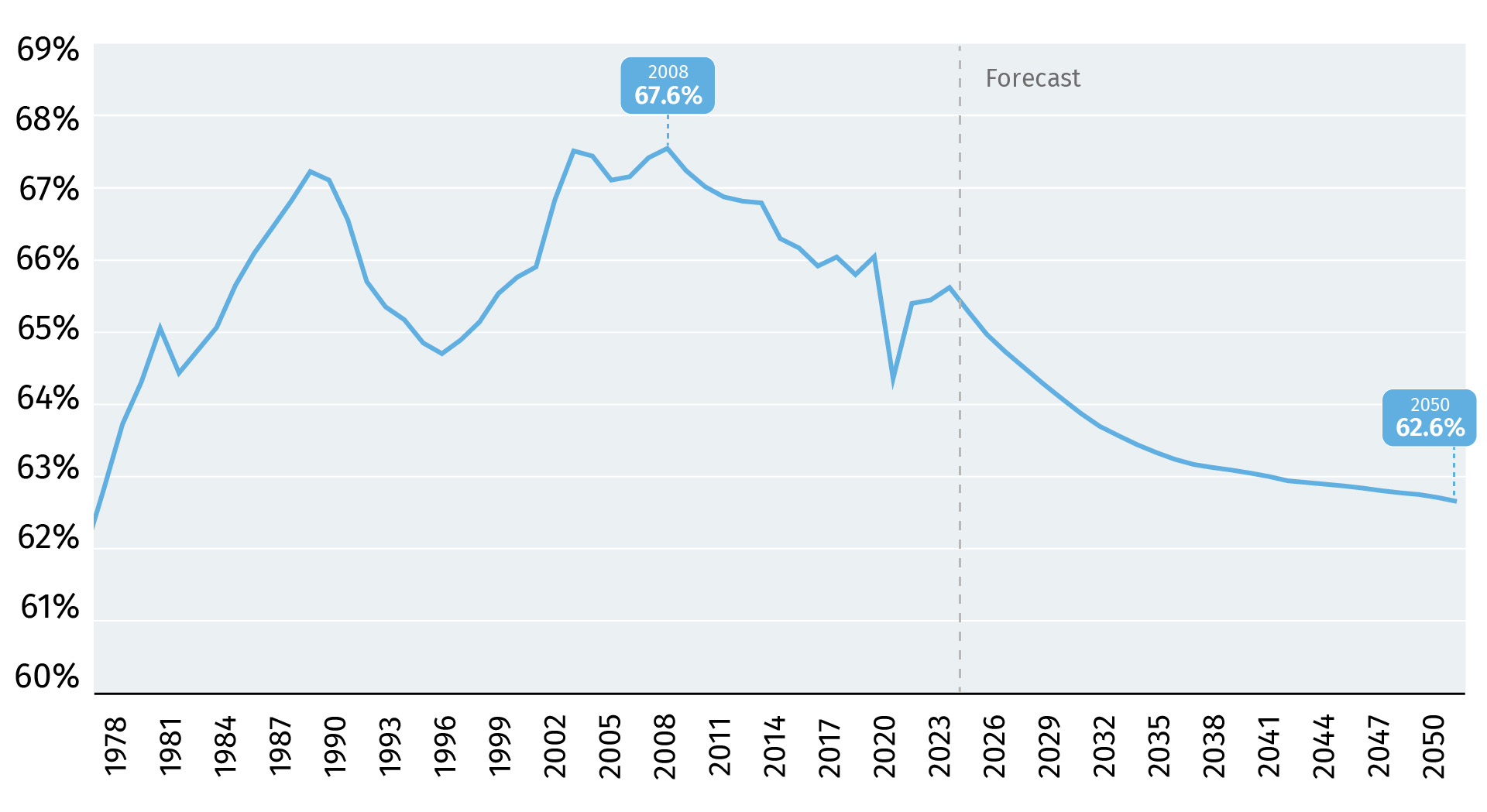

- Proof Point: More immigrants joining Canada’s workforce is helping to mitigate the demographic pressures created by baby boomers retiring as the participation rate of Canadian-born workers continues to decline.

A wave of Canadians leaving the labour force started more than a decade ago as the first of the large baby boomer generation started to hit retirement age. Since then, the share of the Canadian population actively participating in labour markets—that means either working or looking for work—has steadily declined.

An aging population presents challenges for the economy because the demand for goods and services will continue to grow at a faster pace than the labour force needed to meet that demand. The challenge will likely only worsen over the long term as birth rates in Canada continue to run below replacement rates. In addition, it’s also difficult for governments to increase funding for public services like healthcare out of a shrinking tax base (relative to the size of the population.)

Immigration has long been viewed as one way to help offset the impact of an aging population. The participation rate for those born in Canada has continued to fall as more workers retire, but it has risen for immigrants. By late 2020, the share of immigrants participating in the labour force surpassed that of the Canadian-born population. In early 2024, the participation rate of immigrants outperformed Canadian-born workers by 2%.

Immigrants are retiring later and seeing smaller wage gaps

Part of the immigrant outperformance is driven by the fact that they are on average younger. Immigrants have also been retiring later than Canadian-born workers, which is helping to further soften the wave of retirements. In particular, immigrants aged 55 and above have a much higher participation rate compared to those in the same age bracket who are born in Canada. The average retirement age among immigrant workers over the last decade is around 66, according to our calculations. That’s two years older than the average retirement age of 64 for Canadian-born workers.

Older immigrants are participating more in the labour force

%, participation rate for workers 55 and above

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics calculations

Still, delayed retirements aren’t always a good thing for workers, especially when they are driven by necessity, such as affordability challenges and a lack of savings rather than by choice. However, the outperformance of older immigrant workers has come with better labour market outcomes. The employment and wage gaps between immigrants and Canadian-born workers have been narrowing over the last decade.

By late 2023, the gap in nominal earnings between immigrant and Canadian-born workers dropped to its lowest level on record. A recent report from Statistics Canada cited several factors driving these improvements including changes to the immigration selection process since the early 2010s, and a relatively robust labour market backdrop in the late 2010s and 2022. Immigrant workers’ nominal wages are still lagging those of Canadian-born workers for most occupations. But, in specific fields such as natural and applied sciences and art, culture and recreation, they are earning higher hourly wages.

Immigrant workers in Canada are seeing smaller wage gaps

Wage gap measured as share of non-immigrant workers’ average hourly earnings

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics calculations

Labour shortages will worsen over the long run

Immigration won’t be able to solve labour shortage issues in the longer run, as immigrants will also boost overall consumption and lead to more demand for workers. While labour shortages have been easing over the last year as the economy buckles under the weight of elevated interest rates, they are set to come back as the economy recovers. Our forecast is for the Canadian economy to start rebounding over the second half of this year as interest rates start to move lower and households move beyond the shock of higher borrowing costs.

Aging demographics means persistent declines in participation

%, participation rate, 15+

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics projections

All that will happen as the population continues to age. We expect Canada’s labour force participation rate will drop by more than 2% over the next decade to 63.3% in 2035. That is the lowest level since late 1970s. Against that backdrop, rising participation among immigrants – as they are set to take up an increasingly larger share of a shrinking labour force – will continue to help mitigate those challenges facing the economy.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic analysis and is responsible for projecting key indicators including GDP, employment and inflation for Canada and the US.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More