- Rising prices and borrowing costs will impact all Canadian households—but particularly those with lower incomes.

- A return of the overnight rate to 2% will hike average Canadian household debt payments by nearly $2000, or 15%, next year.

- But the debt service ratio of low income Canadians will rise much faster – at twice the speed of high income households through 2023.

- $300 billion in pandemic savings could soften the blow—but lower income earners hold less than half the savings of higher earners.

- The bottom line: low income Canadians will be most squeezed by rate and price hikes—a burden that will only grow heavier into 2023.

The debt story: COVID-19 boosted the debt held by Canadians

Mortgage debt not only surged during the pandemic, it exploded. As many Canadians sought more living space amid low borrowing costs, mortgages grew by an average $150 billion per year in 2020 and 2021—almost doubling the annual growth rate between 2015 and 2019. By the end of 2021, mortgages accounted for over 70% of all household debt. By comparison, the amount of consumer credit (credit cards, personal loans, and lines of credit), declined in 2020.

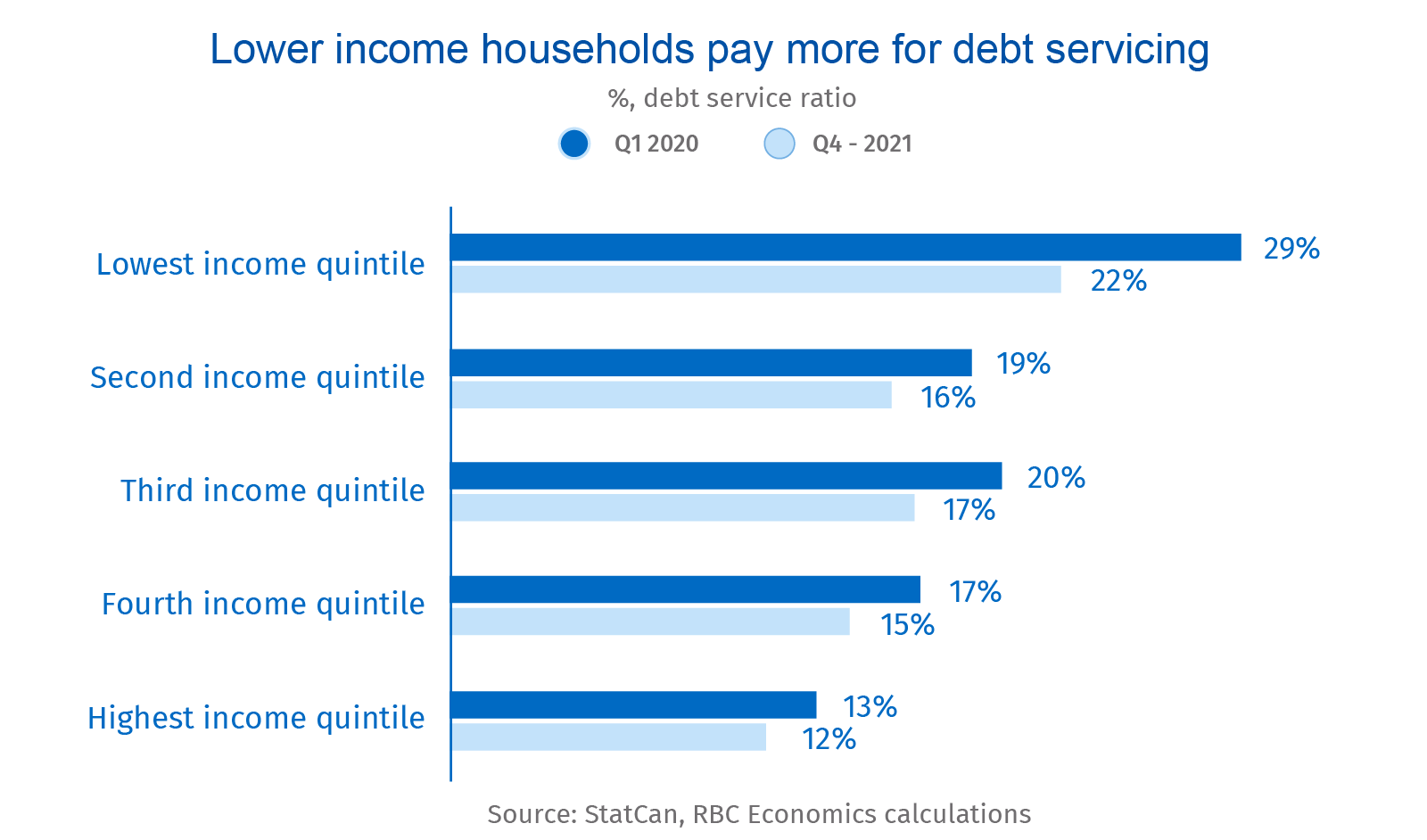

As interest rates march higher—we expect the overnight rate to hit 2% by October, a projection that increasingly looks conservative—borrowing costs for Canadians will also rise, leaving the average Canadian household to spend almost $2000 more in debt payments in 2023. This will erode spending power, especially for the lowest earning fifth of households which spend 22% of their after tax income on debt servicing (including mortgage principle and interest payments). By contrast, those in the highest income quintile spend just half of that amount. Lower income Canadians will also see their debt service ratio (the amount of disposable income needed to meet debt payments) increase much faster through 2023—at twice the speed of the highest income households.

The savings story: low income households have a smaller cash cushion

The pandemic may have boosted debt but it also left Canadian households sitting on $300 billion in savings. That’s a huge backstop—enough to cover about a year and a half of total Canadian household debt payments.

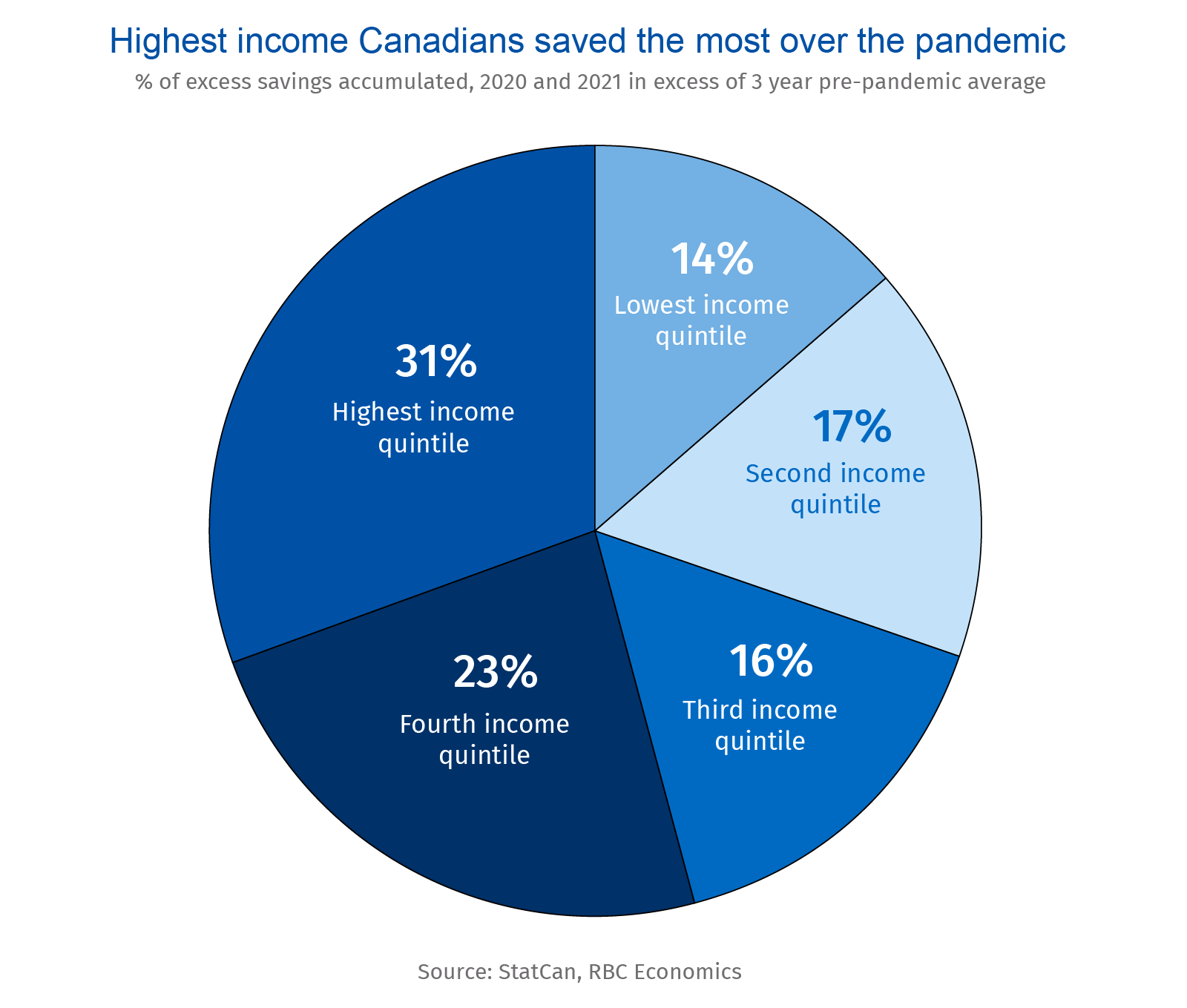

But those savings aren’t evenly distributed. While the top income households (those earning ~$178,000 a year) retain almost a third of the total, the lowest income Canadians (earning ~$34,000 a year) hold less than a fifth. For these households, a large portion of excess savings wasn’t socked away, but was used to pay down consumer debt. These households now have a much smaller cushion against rapidly rising borrowing costs.

The inflation story: surging prices will pinch these Canadians hardest

And rising debt payments aren’t the only things biting into households’ real income. Canada’s March CPI reading hit 6.7%, with just about everything outside of clothing and footwear growing more expensive, more quickly. These price hikes will cut more deeply into the purchasing power of lowest income Canadians, who tend to spend a much larger share of their earnings on consumer purchases.

In the current environment, pre-pandemic 2019 purchases would soak up 10% more these households’ disposable income, compared to just 3.5% more for the highest income households.

Finding the sweet spot: aggressive rate hikes risk bigger slowdown

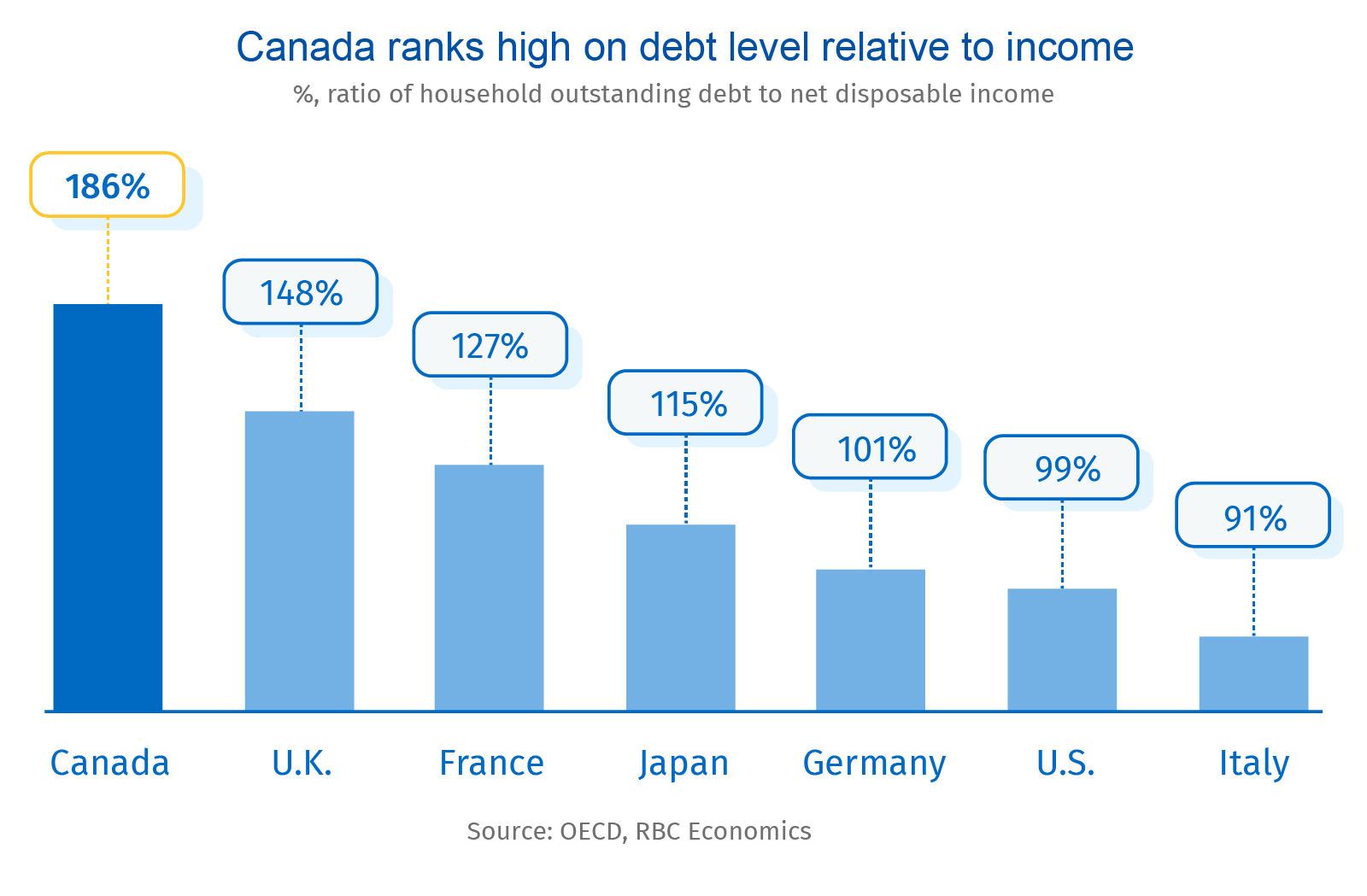

Tight labour markets will continue to push wages higher and together with the savings stockpile, this will sustain consumer spending in the near-term. But Canadians are already among the most indebted in the world. And even after accounting for wage growth, an accelerated increase in the overnight rate will push the share of disposable incomes spent on debt back over pre-pandemic levels. This increase, combined with soaring prices for everyday goods, will bite hard into the real earnings of lower income Canadians.

But a more aggressive rate increase—such as a hike above 3%, the top end of the estimated long-run ‘neutral’ range—would tap the brakes on economic growth that’s already being curbed by production capacity limits and labour shortages. The challenge for the Bank of Canada at this point in the economic cycle is to hike interest rates enough to rein in prices, relieving pressure on Canadians, without sparking a downturn. That will be no easy task.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic trends and is responsible for projecting key indicators on GDP, labour markets as well as inflation for both Canada and the US.

Nathan Janzen is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More