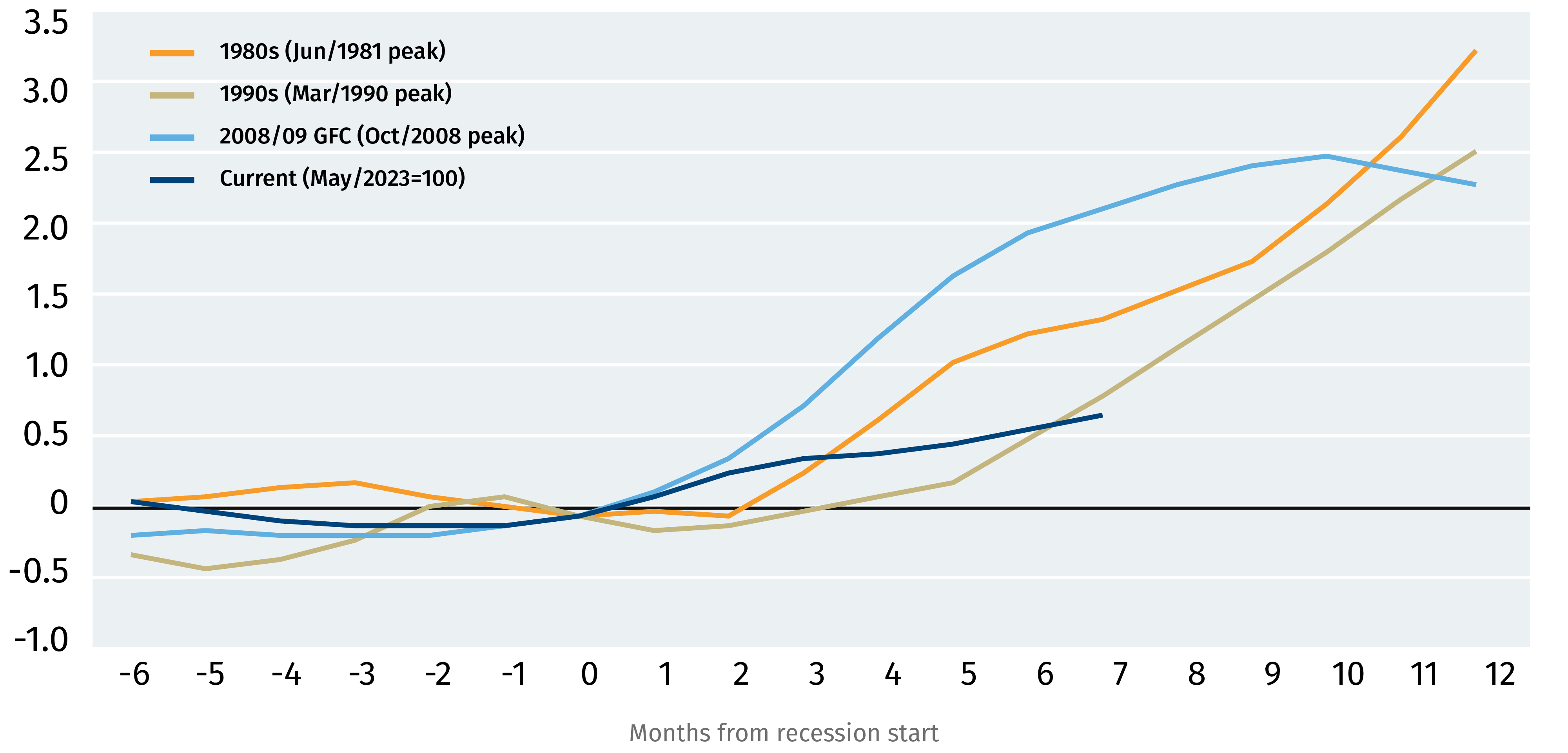

- The magnitude and pace of Canada’s rising unemployment rate are consistent with trends observed during past recessions.

- Unlike prior recessions, though, the increase to-date has come without a surge in layoffs – it’s rather taking more time to absorb newly available workers as the population grows rapidly.

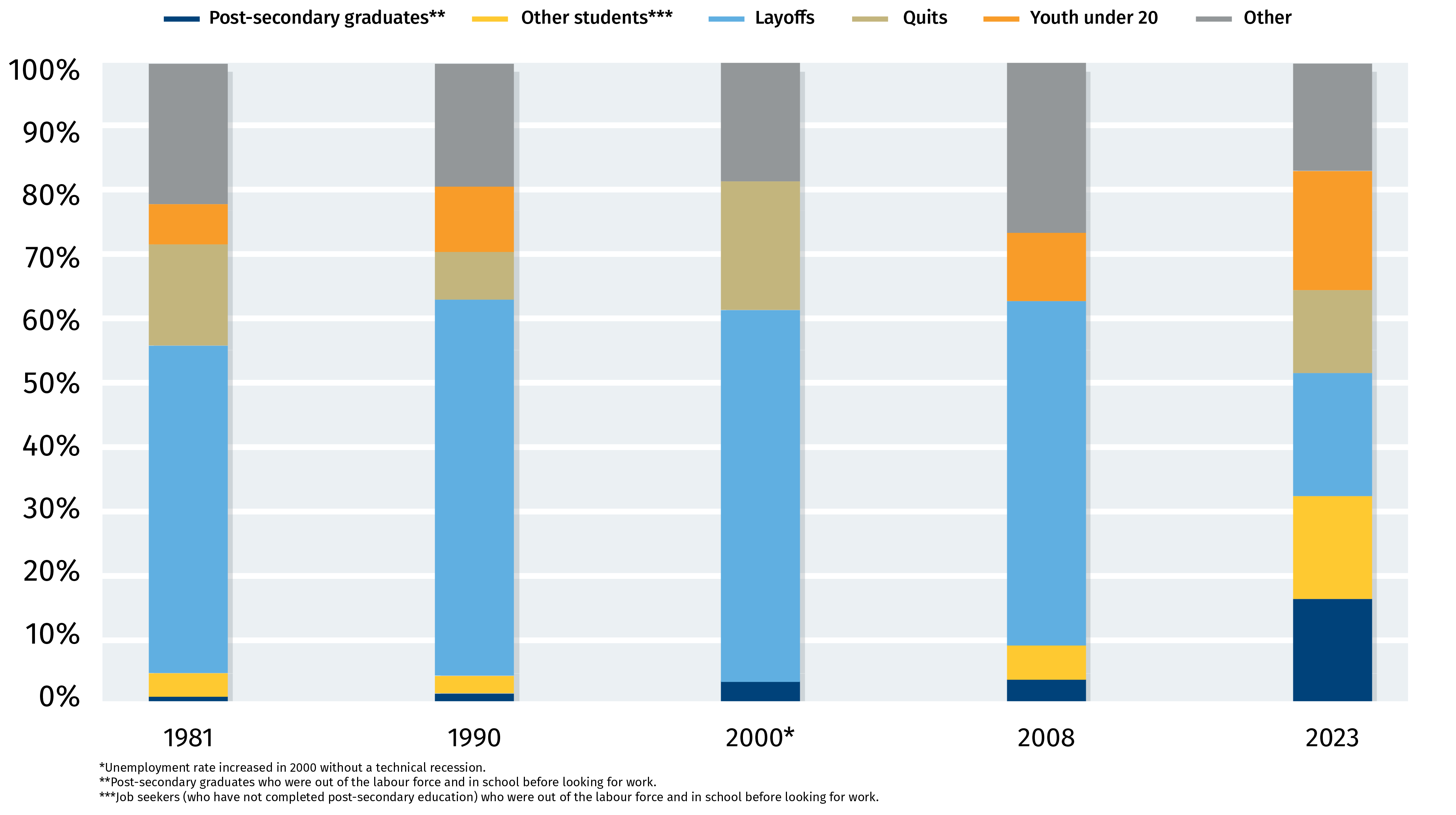

- But it’s students and new graduates rather than new arrivals to Canada that have been driving the increase.

- Roughly half of the 0.8 ppt increase in the unemployment rate since April has come from longer job searches for students and new graduates who weren’t previously in the labour force.

- The Bottom Line: Longer job searches for students and new graduates have been a larger factor behind a higher unemployment rate in Canada to-date than layoffs or new arrivals from abroad. To-date, the increase in unemployment has come without a net decline in employment counts. But the slowdown is not over yet – we look for unemployment to continue to edge higher over the first half of 2024.

Canada Unemployment Rate Recession Comparison

Percentage point increase, 3-month rolling average

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics Research

Canadian unemployment looks recessionary even without layoffs

Since April, Canada’s unemployment rate has risen by 0.8 percentage points. An increase of that magnitude over that period of time usually only happens during a recession.

The rise in the unemployment rate is tracking at the “mild” end of historical downturns. And we do expect GDP to post a second consecutive small decline in Q4 of 2023 – and per-capita output has already declined for five consecutive quarters as of Q3 last year.

But this labour market slowdown has been different than in the past. With population growth surging, higher unemployment has come predominantly from slower hiring rather than more firing. National employment counts are still rising, but no longer quickly enough to absorb new labour market entrants.

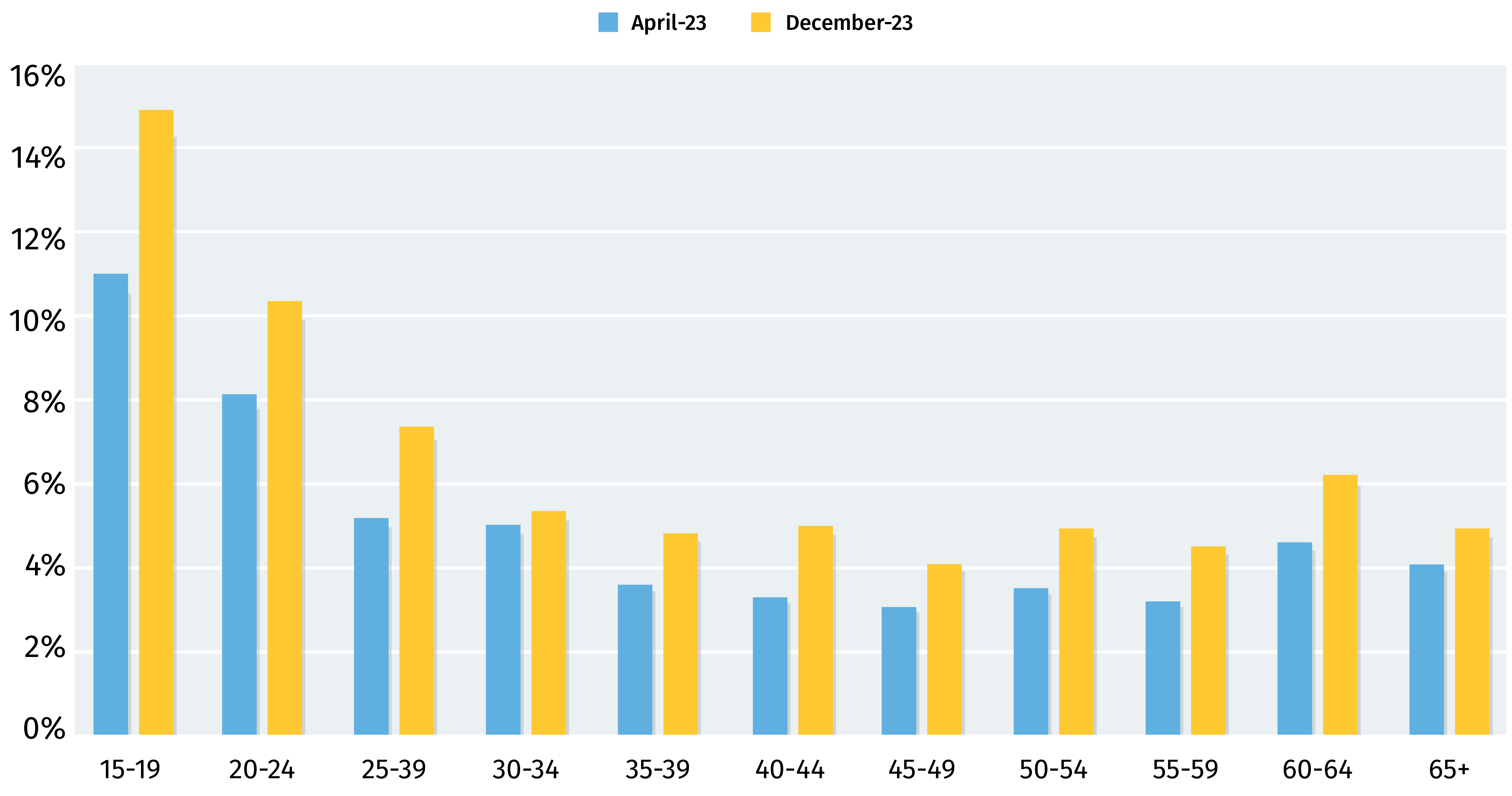

Unemployment rates rise by larger margin for early career cohorts

Unemployment rate by age group (seasonally adjusted)

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

Record population growth continues to support employment gains

Slight growth in Canada’s job numbers alongside higher unemployment has been a byproduct of Canada’s record population growth in 2023 – fueled by surging numbers of immigrants. That population growth has masked a lot of the country’s economic weakness.

Since April, Canada has added 369K new workers to the labour force. But the number of employed workers has only grown by less than half of that number- 182K- with the remaining new labour force participants counted as still looking for work and unemployed.

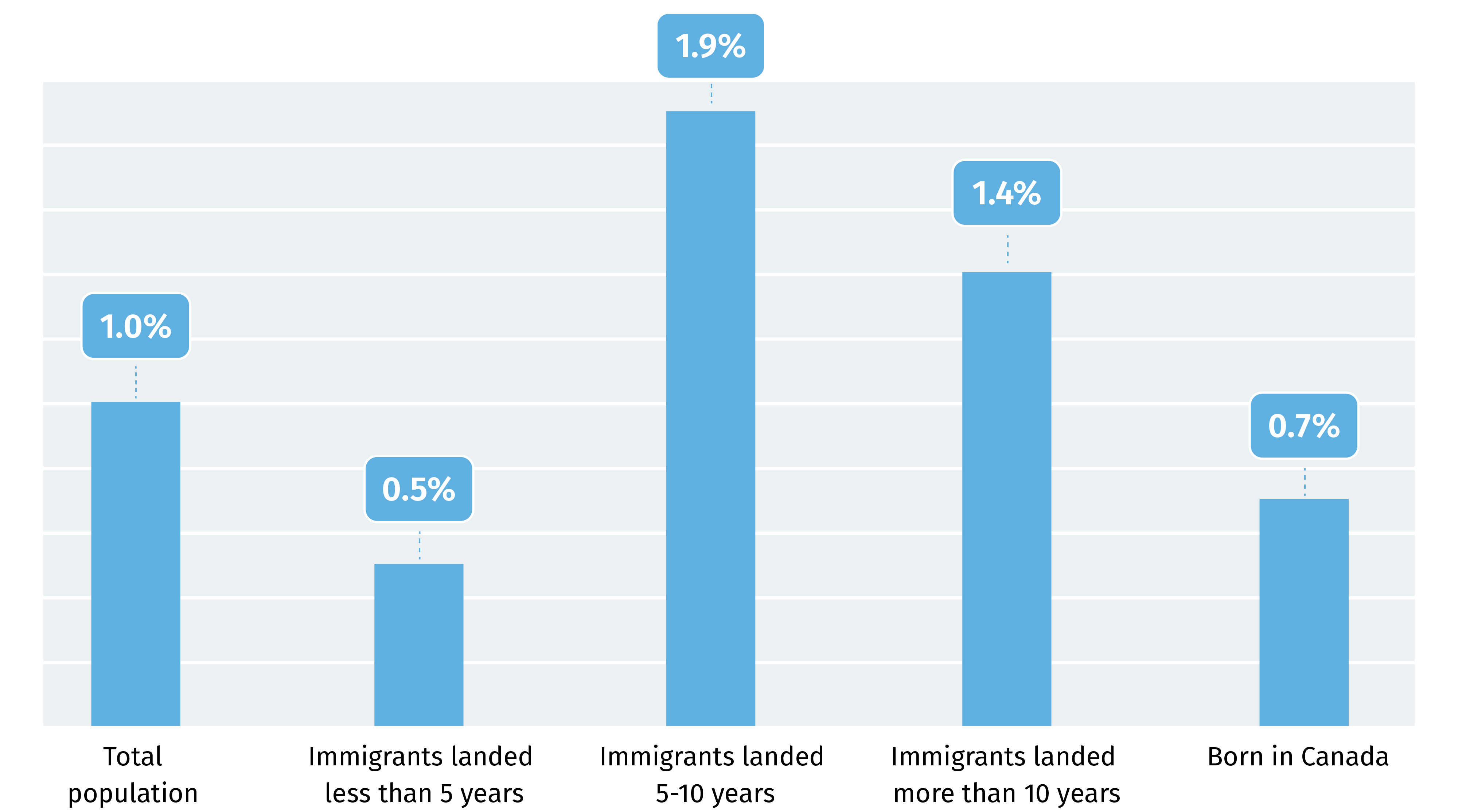

Rise in unemployment rate is sharper for immigrants

landing 5+ years ago

Three-month moving average percentage point change in unemployment rate for population

aged 15+ between April and December 2023 (seasonally adjusted)

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

Students and recent grads are driving the uptick in unemployment

But, while new arrivals to Canada have been driving population growth higher, it’s actually students and new graduates that have been driving unemployment rate increases.

The unemployment rate for recent newcomers (immigrants that arrived less than 5 years ago) has increased by half as much as the total population since the spring. This is despite the fact that immigrants who landed in Canada more than 5 years ago have been disproportionately represented in Canada’s job seeking population. Fully half of the total 0.8 ppt increase in the unemployment rate has come from those that were previously not in the labour market because they were in school. That is a substantially larger share than the roughly one-third coming from layoffs.

Of course, it is not unusual for younger workers to bear the brunt of a labour market slowdown. Unemployment rates have historically risen faster for younger cohorts during recessionary periods – and this cycle doesn’t appear to be an exception. Not only are employees with the shortest tenures and the least experience typically the first to be let go, younger workers also tend to be concentrated among a few industries – like retail trade, food, and accommodation. This leaves them particularly vulnerable to shocks which disproportionately impact these industries.

Students a driving force behind uptick in unemployment

Contributions to increase in unemployment (8 months past pre-recession level),

seasonally-adjusted

Source: Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

But there is something more happening, and it has to do with younger people who are about to enter the labour market. The share of younger Canadians with post-secondary education has continued to rise, and hiring demand has softened sharply in industries like professional services and finance jobs where there’s a higher number of recent post-secondary graduates struggling to find a job.

To date, students and new graduates have been most impacted by loosening labour market conditions. Though we’ve yet to see the full impact of the ongoing labour market downturn, a rapid decline of open positions will likely remain a challenge for newcomers and Canada’s graduating classes in the near term.

Carrie Freestone is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group and is responsible for monitoring key indicators focusing on consumer spending and household debt as well as labour markets, GDP, and inflation. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from Queen’s University and a Master of Arts in Economics from the University of Ottawa.

Rachel Battaglia is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the Macro and Regional Analysis Group, providing analysis for the provincial macroeconomic outlook and budget commentaries.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More