- Services are becoming an essential part of Canada’s manufactured goods—suggesting a push to revitalize domestic manufacturing could accelerate both our goods and services trade.

- In the auto sector alone, nearly 40% of the value added in exports now comes from services (for instance, the design of the vehicle or the software it carries), up 8% from the mid-1990s.

- And roughly 40% of manufacturing jobs linked to goods exports are actually services roles.

- Yet almost half of the services embedded in our goods exports are sourced from abroad, due in part to significant foreign ownership in Canada’s manufacturing sector.

- The bottom line: As Canada partners with allies in regional supply chains, the services content in goods trade can’t be ignored. Expanding our footprint into this area could reap benefits across an array of sectors.

Services are more important to Canadian supply chains than ever

The traditional way of measuring trade is through gross exports. And by this metric, services account for less than one-fifth of all trade. But when tallying up all of the domestic value-added within Canadian exports, the service sector’s share jumps to one half. Among the factors driving this rise is the so-called “servicification” of manufacturing—that is, the factory sector’s increasing reliance on services like software, design and more. Sales of services bundled with goods—things like installation, ongoing service and maintenance—are also growing.

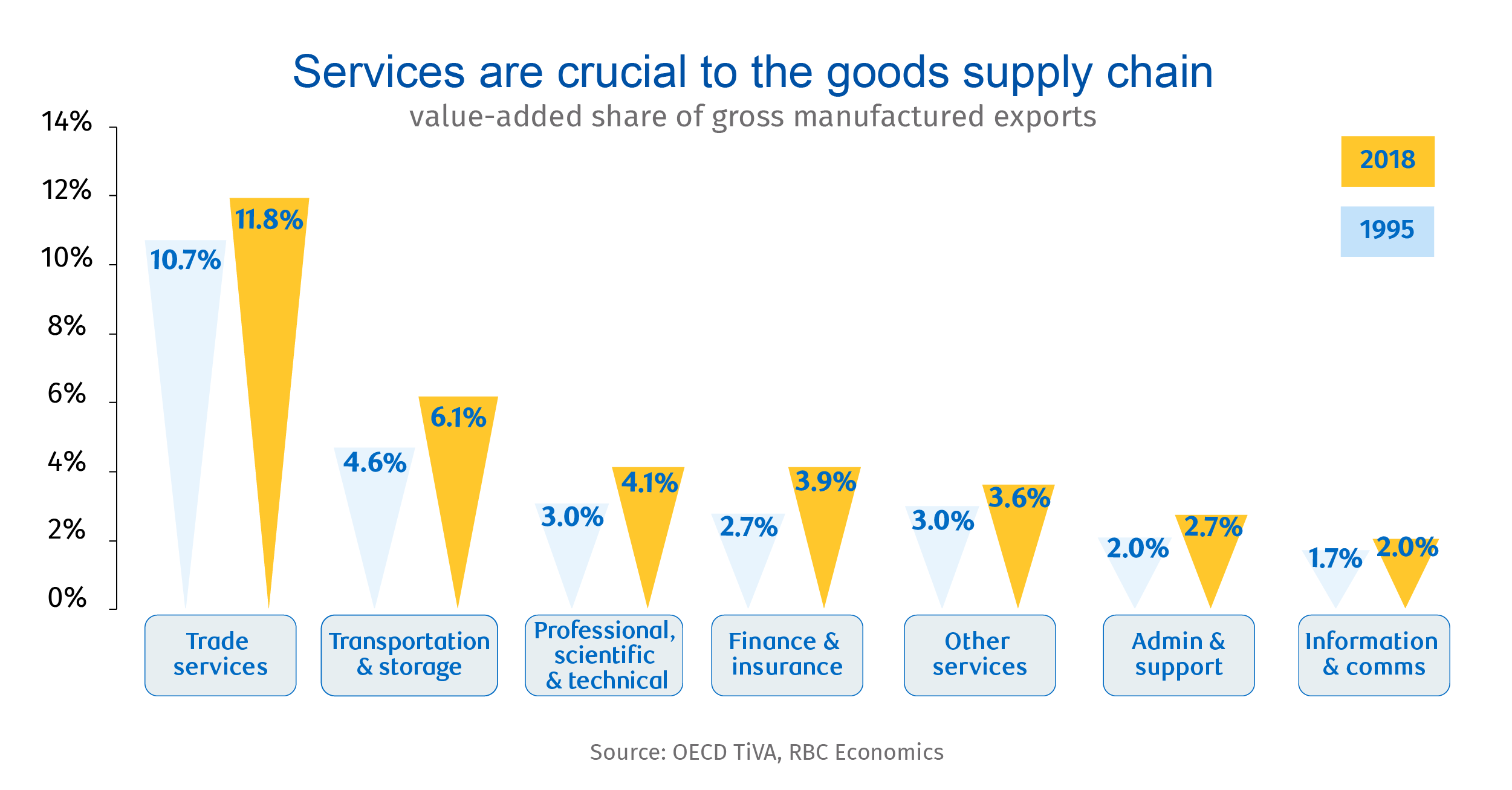

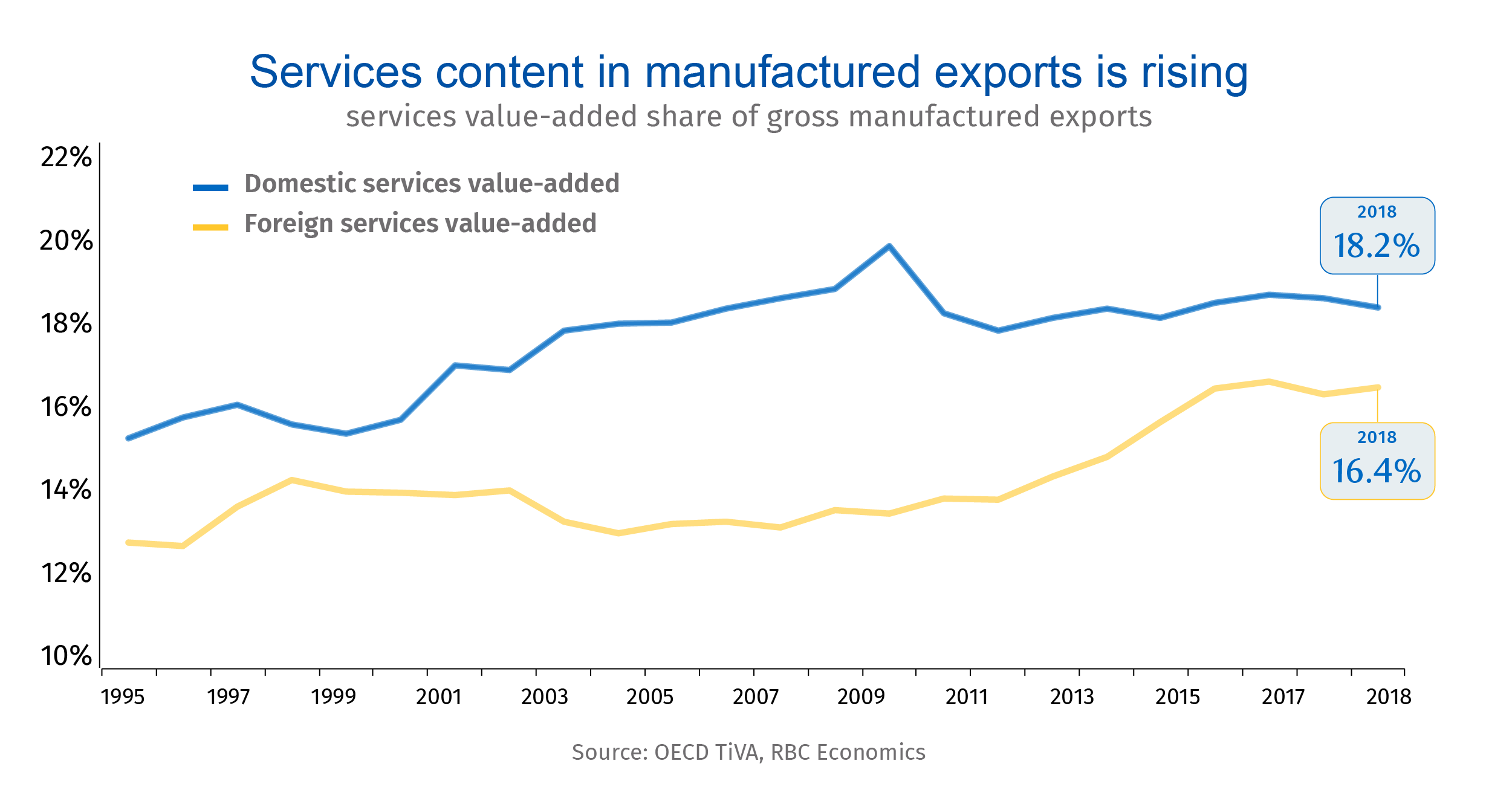

The OECD’s Trade in Value Added (TiVA) database shows services accounted for 34% of the value-added in Canada’s manufactured exports in 2018, up from 28% in 1995. Trade services, transportation and warehousing, finance and insurance, legal, accounting, advertising, architecture, engineering, design and administrative and support services all represent growing links in manufacturing supply chains.

They are also critical to employment. Statistics Canada estimates manufactured exports indirectly support more than 800,000 jobs, most of which are in the services sector. And with occupational data suggesting roughly four in 10 manufacturing employees perform services activities, a sizeable share of the 650,000 manufacturing jobs linked directly to exports are actually services roles. These jobs will only become more important as artificial intelligence, robotics and and machine learning drive the factories of the future.

This suggests the benefits of invigorating domestic manufacturing—building out supply chains in emerging, innovative and fast-growing industries like clean tech and EVs—could extend well beyond goods trade.

Much of the services in our goods aren’t made in Canada

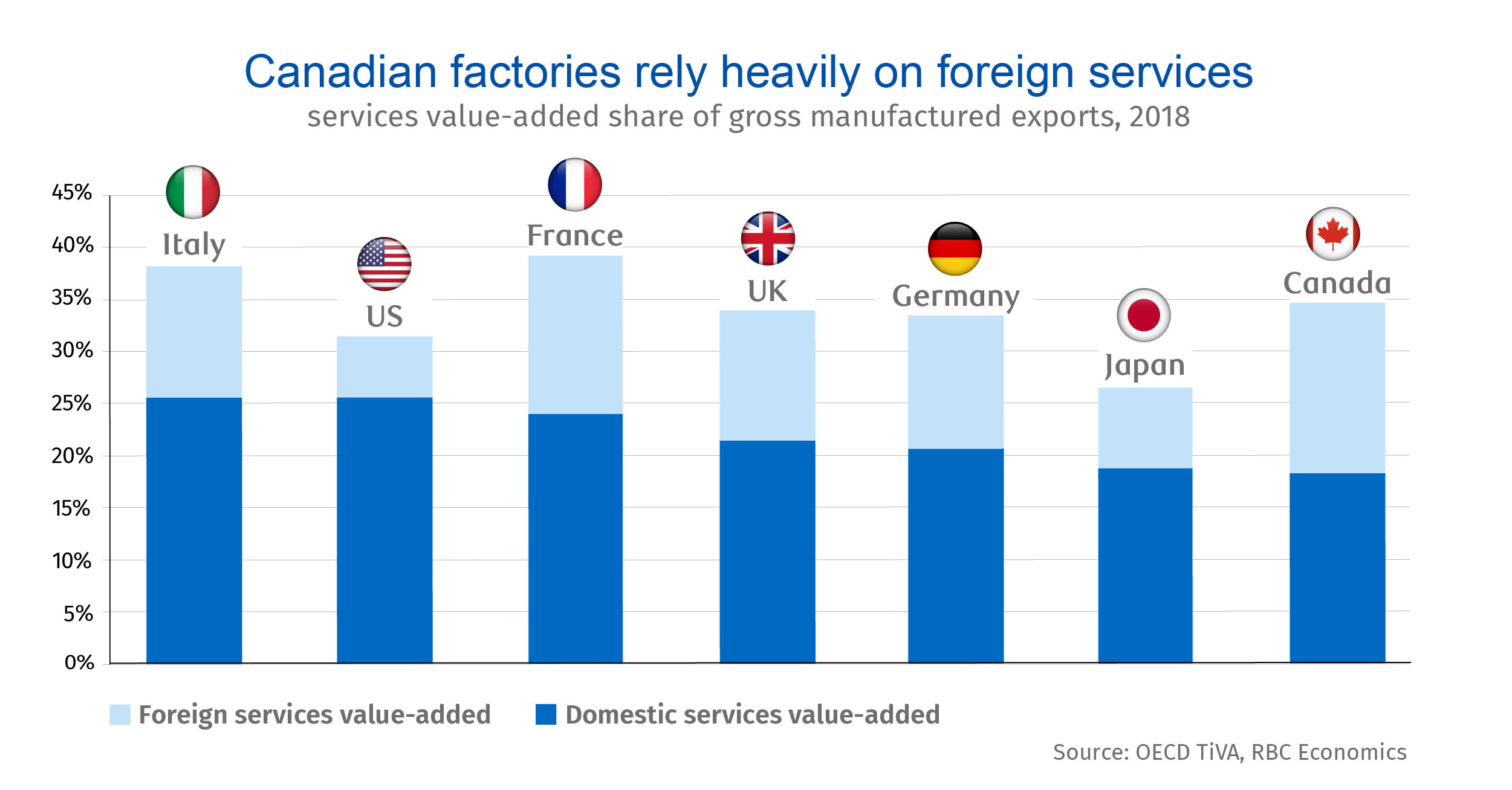

The internationalization of services within global value chains has taken off among OECD economies, with manufacturers increasingly sourcing services inputs from abroad. In Canada, the manufacturing sector has seen growth in both domestic and imported services. But it’s the services coming from beyond our borders that are responsible for much of the increase in services value-added in recent years. In fact, among G7 economies, Canada’s manufacturing sector is the most reliant on foreign services—and has the least domestic services content in its exports.

That’s partly due to the large presence of foreign multinational enterprises in Canada (MNEs), which account for nearly two-thirds of our manufactured exports. These Canadian affiliates import services from their parent companies and likely leverage that company’s relationships with foreign services firms.

Indeed, manufacturing subsectors dominated by foreign MNEs tend to rely more on imported rather than domestic services inputs. For instance, foreign MNEs account for more than 80% of Canadian exports in the transportation equipment and basic metals manufacturing, sectors that source more than half of their services inputs from abroad.

Tight trade ties with the U.S. make boosting services content a challenge

Canada’s close trading relationship with the U.S. could make expanding our contribution of services in goods trade a challenge. The U.S. has the lowest foreign services content in its manufactured exports among OECD countries, consistent with the low share of foreign ownership in the sector.

When it comes to services like ground transportation, warehousing, and finance and insurance, Canada’s factories lean mostly on domestic providers. But they rely more foreign firms for services like professional, scientific and technical, administrative and support, and computer programming, consulting and information services. These are industries in which Canada has plenty of capability.

And with so much of the value-added in goods production and exports coming from the services sector, these critical supply chain links can’t be ignored. For instance, much of the focus in Canada’s burgeoning EV sector has been on securing assembly operations, maximizing investment in battery production and other parts of the physical supply chain. That’s clearly a priority—but we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that nearly 40% of the value added in auto exports comes from services.

Simply replicating the auto sector’s existing services supply chain could leave Canadian services firms on the sidelines of a fast-growing EV industry.

Services should be a focus of Canada’s efforts to attract investment

The significant presence of services in Canadian goods trade suggests the sector is more exposed to shifting trade winds than many realize. There are many issues prompting a rethink of globalized supply chains, including transportation bottlenecks, ensuring reliable supply of inputs, concerns about national security and reliance on foreign firms, and leadership in emerging technologies. But these apply not just to the physical flow of goods but also to the services content within them.

Canada and its trading partners are adopting activist industrial policies to build out domestic manufacturing. The U.S.’s recently passed Inflation Reduction Act includes more than US$60 billion in support for clean manufacturing industries. As policymakers think about strategic reshoring or partnering with allies in regional supply chains, the services embedded in goods exports must also be a key consideration. That means governments should look at broader supply chain links when weighing support for manufacturers. And efforts to champion home-grown companies could pay even greater dividends if they partner with domestic services suppliers to a greater extent than foreign firms.

Josh Nye is a senior economist at RBC. His focus is on macroeconomic outlook and monetary policy in Canada and the United States. His comments on economic data and policy developments provide valuable insights to clients and colleagues, and are often featured in the media.

Naomi Powell is responsible for editing and writing pieces for RBC Economics and Thought Leadership. Prior to joining RBC, she worked as a business journalist in Canada and Europe, most recently reporting on international trade and economics for the Financial Post.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More