- Higher consumer spending fueling the U.S. economy’s outperformance to-date

- Higher U.S. consumer spending can be explained by a greater willingness to spend out of pandemic savings.

- In Canada, savings are still high, but are increasingly shifting into term deposits and other investments that are less likely to be spent in the near-term.

- Households in both countries are vulnerable to a pullback in labour markets

- Bottom Line: Canadian household spending is already pulling back and we expect the U.S. consumer will follow as savings run out. The drawdown of U.S. households’ pandemic savings has delayed but not prevented a slowdown in consumer spending. The weakening economic growth backdrop is expected to push both the U.S. Fed and Bank of Canada to begin cutting interest rates next year.

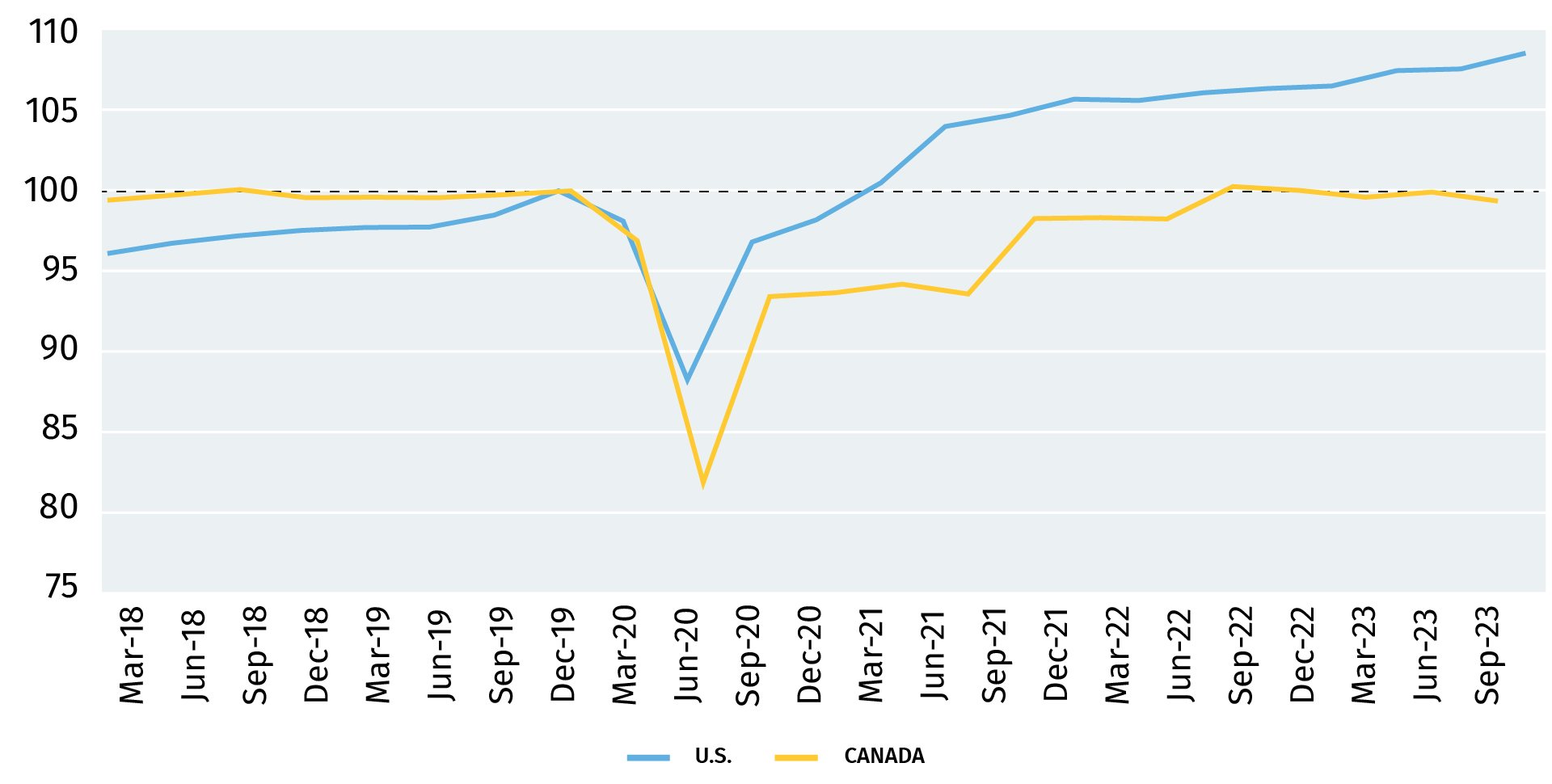

U.S. per capita consumption is still trending higher

Real per capita consumption, seasonally adjusted, Q4 2019=100

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

The U.S. economy has significantly outperformed Canada this year

Canadian consumers have begun to pare back ahead of the holiday shopping season. Retail sales outright declined in Q3 on a quarter-over-quarter annualized basis, accompanied by a pullback in discretionary services sector spending. And those spending totals look significantly worse on a per-person basis given high rates of population growth – the 1.4% year-over-year decline in household per-capita spending as of Q2 is the largest decline since the 2008/09 recession outside of the pandemic.

But south of the border, consumer spending has yet to soften. The U.S. has significantly outperformed Canada this year, with per capita consumer spending continuing to soar well-above pre-pandemic levels. Per-person U.S. spending was running almost 2% above year-ago levels as of Q3.

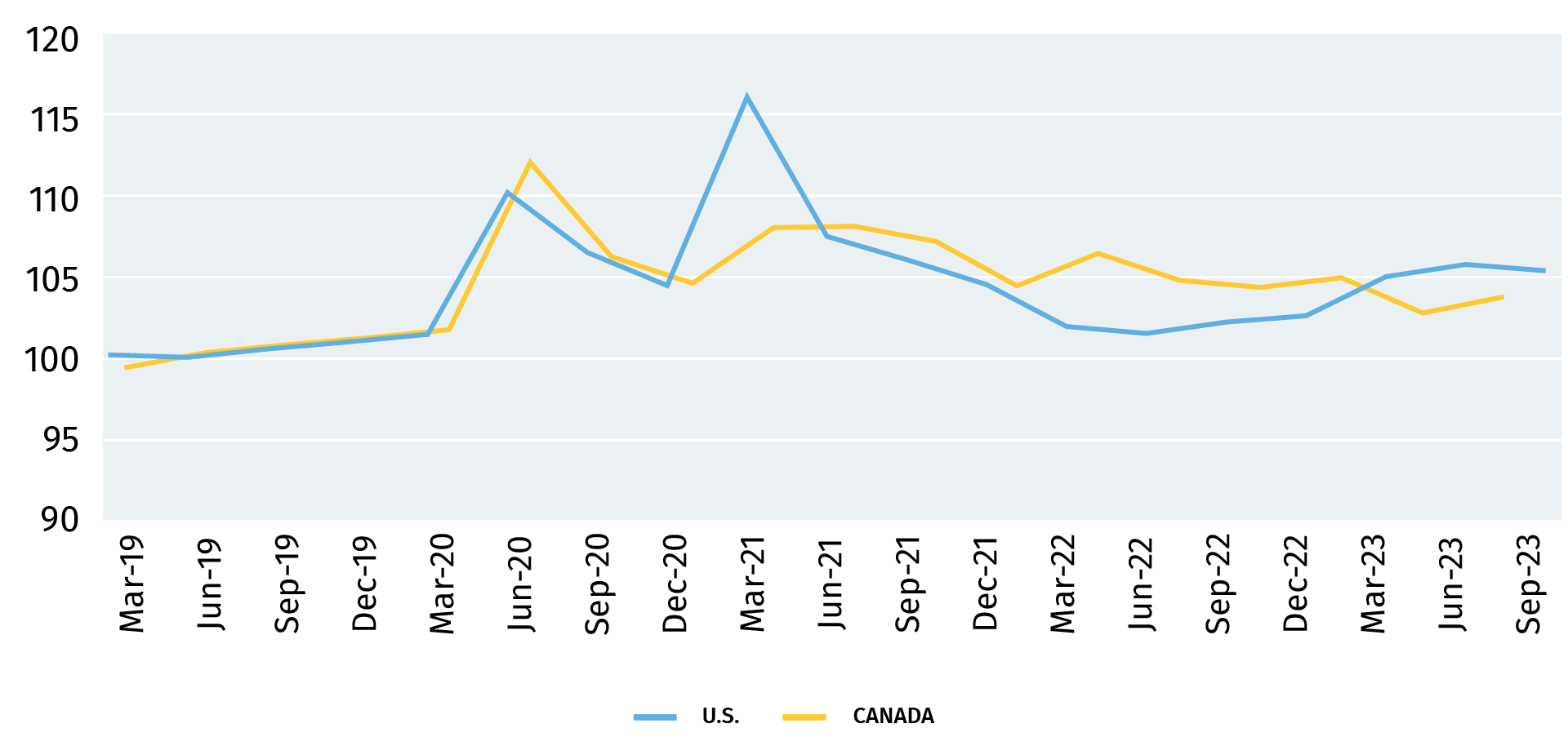

Real per capita disposable income trends similar across U.S. and Canada

Real per capita personal disposable income, seasonally adjusted, 2019=100

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

Americans more willing to dip into savings stockpile to fuel spending

In the U.S., a larger government budget deficit is helping prop up labour markets. But in both countries, there has been little growth in disposable income since 2019 after adjusting for inflation. U.S. real household disposable incomes are running about 5.2% per-person above pre-pandemic levels versus 3.3% in Canada – not a big enough gap to explain the ~8.0% gap in per-person consumption levels.

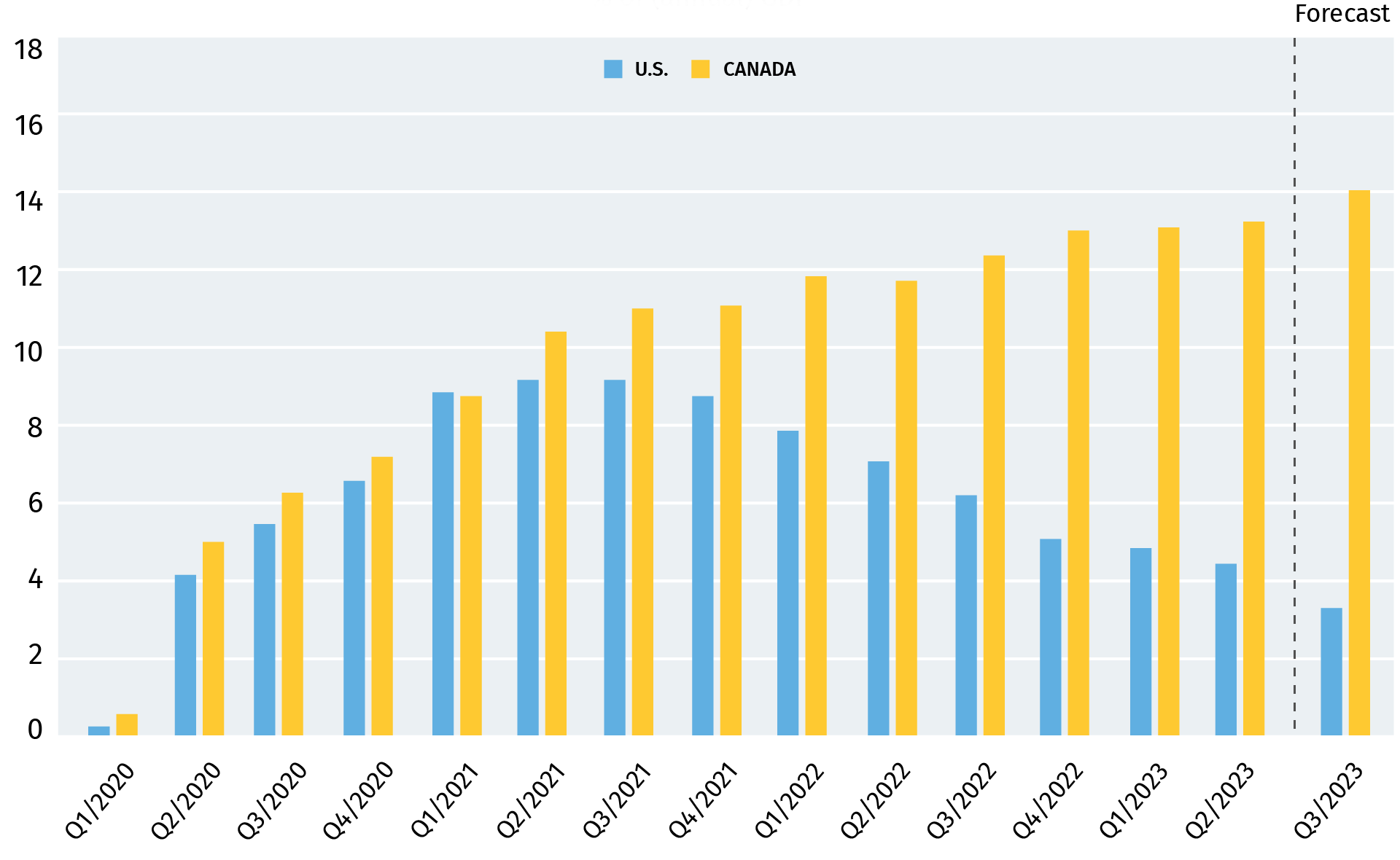

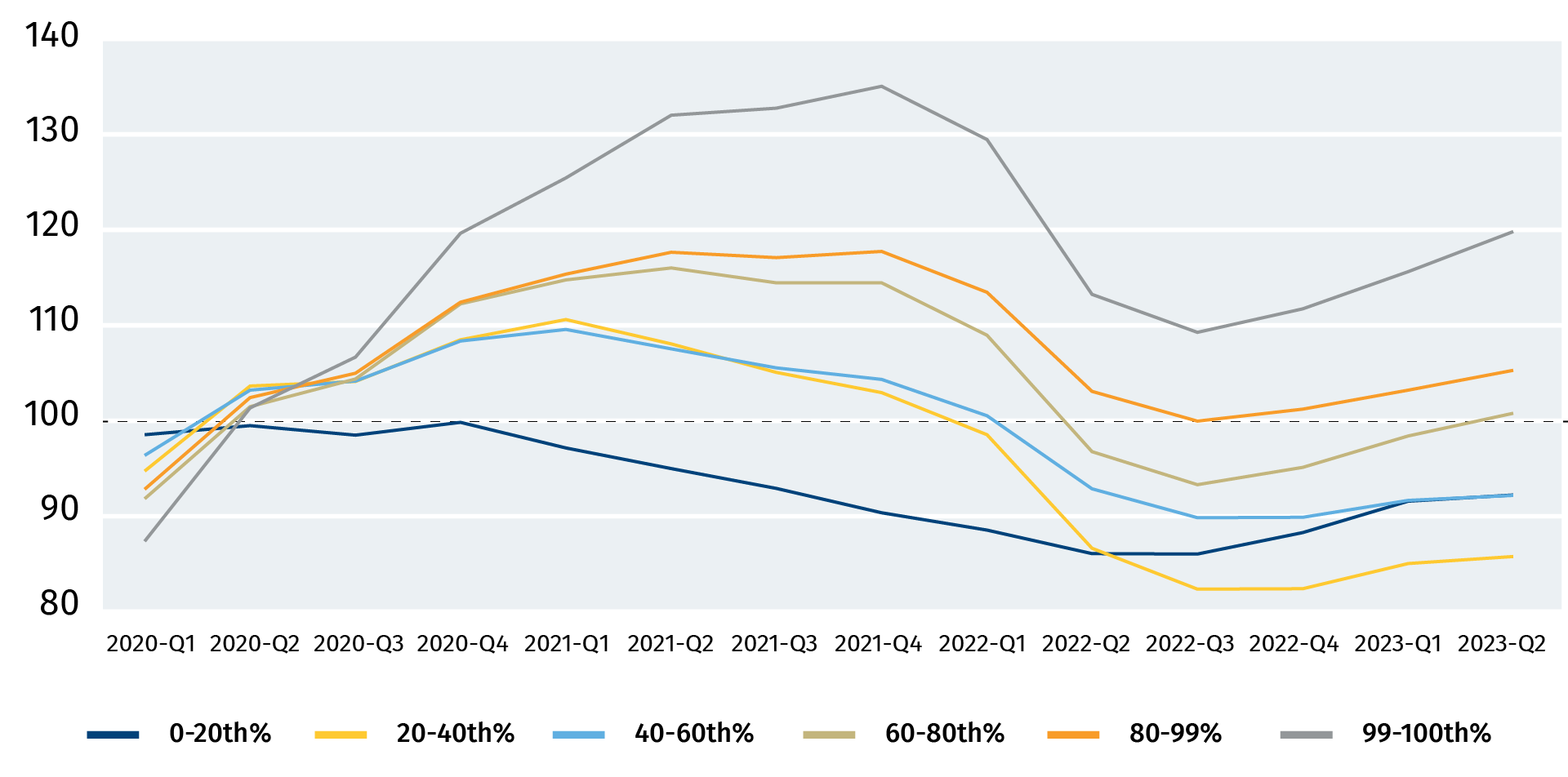

But households in the U.S. have been more willing to spend out of ‘excess’ pandemic savings. Households in both the U.S. and Canada built up large amounts of savings during the pandemic thanks to government transfers that propped up incomes at a time when there were fewer spending opportunities due to lockdowns. In the U.S., cumulative “excess” savings peaked at over 9% of GDP two years ago and have shrunk to ~3.5% of GDP currently. And most American households are now worse off than they were before the pandemic from a savings perspective. After adjusting for higher prices, the bottom 80% of income earners have less net financial assets than they did before the pandemic with only the top 20% of income earners having retained some savings.

Americans are also less sensitive to higher interest rates in the near term, as it takes longer for these rate hikes to pass through to American households than in Canada. Why is this? In the United States, the typical term length is 30-years, while in Canada mortgage contracts are typically renewed every 5 years or less. Additionally, the U.S. underwent a major mortgage refinancing boom during the early days of the pandemic. Many American households locked in at low rates for decades. So, market interest rate increases pass through more quickly to household debt payments in Canada.

Americans spend & Canadians stockpile ‘excess savings’

% of (annual) GDP

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Statistics Canada, RBC Economics

Canadian pandemic savings are less likely to be spent

And Canadian households have been more cautious about dipping into pandemic savings. The household savings rate in Canada has yet to fall below pre-pandemic levels, which means households are still saving more today out of current incomes than they were previously. The Canadian cumulative household “excess” savings stockpile has grown to roughly $376 billion as of Q2, equivalent to roughly 13% of GDP.

That represents a potentially large buffer for households, but the stockpile is not evenly distributed – the bottom 40% of the income distribution in Canada never actually accumulated savings during the pandemic, they just took on less debt. Actual cash/investment savings are likely concentrated towards the top end of the income distribution, where spending as a share of income is typically substantially lower. And those savings have been shifting into term deposits and investments, which are less likely to be drawn down quickly.

Most of the U.S. population has depleted pandemic savings

Net real financial assets (financial assets less liabilities) by income percentile

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve, RBC Economics

Households in both countries are vulnerable to softening labour markets

U.S. consumption levels are unlikely to last. American households are just as vulnerable as Canadian households to softening labour markets- but for different reasons. American households have fewer pandemic savings to fall back on, should they face unemployment. In Canada, household debt levels are much higher, so an increase in unemployment could impact the solvency of more households more quickly. Unemployment rates are still low in the U.S. and Canada but have begun to edge higher in a pattern that is typical of the early stages of a labour market downturn.

Our expectation is for the U.S. to enter into a recession after Canada, with a 1% pullback in real output in each of Q1 and Q2 next year. Softening growth in the U.S. could add to Canadian growth headwinds by reducing exports. Once the Bank of Canada and Fed move to cool currently restrictive levels of monetary policy, this will alleviate some of the strain on households. For now, Canadians can expect to see softer data coming out of the U.S. in the months ahead.

Carrie Freestone is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group and is responsible for monitoring key indicators focusing on consumer spending and household debt as well as labour markets, GDP, and inflation. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in Economics from Queen’s University and a Master of Arts in Economics from the University of Ottawa.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More