“Can I get my product to global markets?”

It’s a nagging question for Canadian businesses and international investors eyeing new opportunities for Canada to feed the world, become a critical minerals hub, an electric vehicle powerhouse, and export Canadian copper and cheese around the world.

Capacity constraints, labour stoppages, climate-related disruptions, and long project approval times are gumming up the country’s transportation arteries, hurting Canada’s reputation.

It could not come at a worse time. Major incentives in the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) have kicked off a global competition for the coming investment boom as global trade flows are reshaped by energy transition and geopolitics. Canada can claim an outsized share of this investment, but transportation infrastructure—marine ports, airports, railways, roads, and pipelines—that efficiently, reliably, and sustainably connects goods and people to global markets is central to our success.

Industry and governments are rethinking pieces of the country’s transportation system. But an urgent new strategy is needed to reimagine transportation infrastructure holistically, with new, hard assets complemented by investments in data and technology, sector cooperation, smart regulation, and talent. It will be key to unravelling the gridlock, and creating an economy-transforming, free-flowing interprovincial and international trade network.

Canada’s transportation sector is complex and sophisticated, employing 800,000 people and moving $1.5 trillion in goods to and from international markets in 2022.

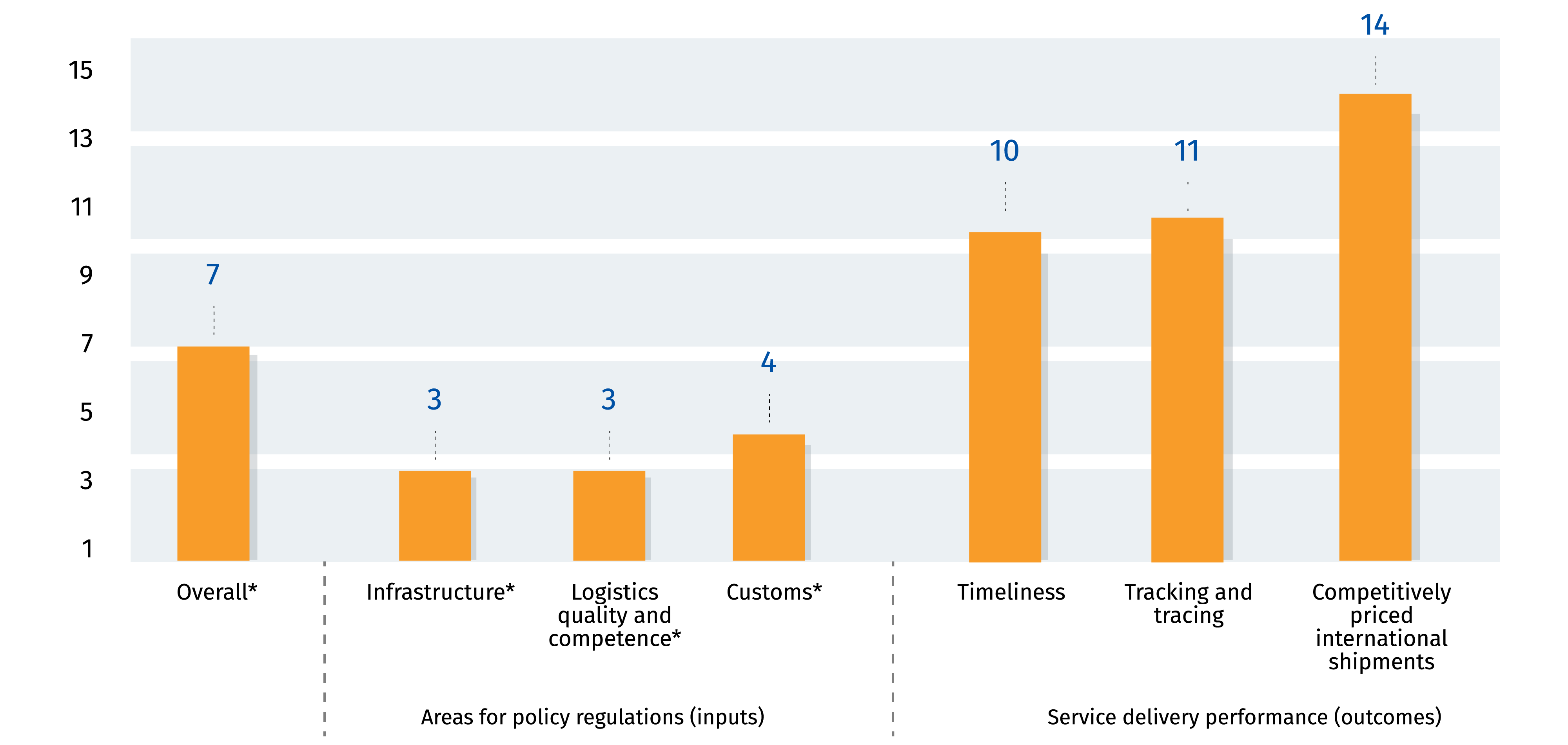

Canada’s transportation sector is complex and sophisticated, employing 800,000 people and moving $1.5 trillion in goods to and from international markets in 2022. Canada recently saw its best-ever 7th place global ranking in the World Bank’s 2023 Logistics Performance Index, driven by improving investment and other supply chain inputs.

Canada recently saw its best-ever 7th place global ranking in the World Bank’s 2023 Logistics Performance Index, driven by improving investment and other supply chain inputs. Canada ranks considerably lower for timely, transparent, and competitively priced movement of goods, with its two-day median port turnaround time twice the OECD average. Truck freight prices are up 25% from pre-pandemic levels.

Canada ranks considerably lower for timely, transparent, and competitively priced movement of goods, with its two-day median port turnaround time twice the OECD average. Truck freight prices are up 25% from pre-pandemic levels. Despite recent improvements, Canada has a history of underinvesting despite an uptick in freight cargo traffic. Seaport engineering investment per unit of cargo handled has only recently recovered from a 20-year deficit.

Despite recent improvements, Canada has a history of underinvesting despite an uptick in freight cargo traffic. Seaport engineering investment per unit of cargo handled has only recently recovered from a 20-year deficit. At least $600 billion in real investment is needed by 2040 to keep pace with Canada’s economic growth. Seizing new export opportunities and making supply chains more resilient, including to the effects of climate change, will require significantly more. The U.S. is investing in its core infrastructure with $550 billion in new federal spending.

At least $600 billion in real investment is needed by 2040 to keep pace with Canada’s economic growth. Seizing new export opportunities and making supply chains more resilient, including to the effects of climate change, will require significantly more. The U.S. is investing in its core infrastructure with $550 billion in new federal spending. Canada’s transport sector has a software investment gap versus U.S. counterparts since 2013, spending on average 35% less per volume of trade.

Canada’s transport sector has a software investment gap versus U.S. counterparts since 2013, spending on average 35% less per volume of trade.Invisible when it works: Canada’s transportation infrastructure

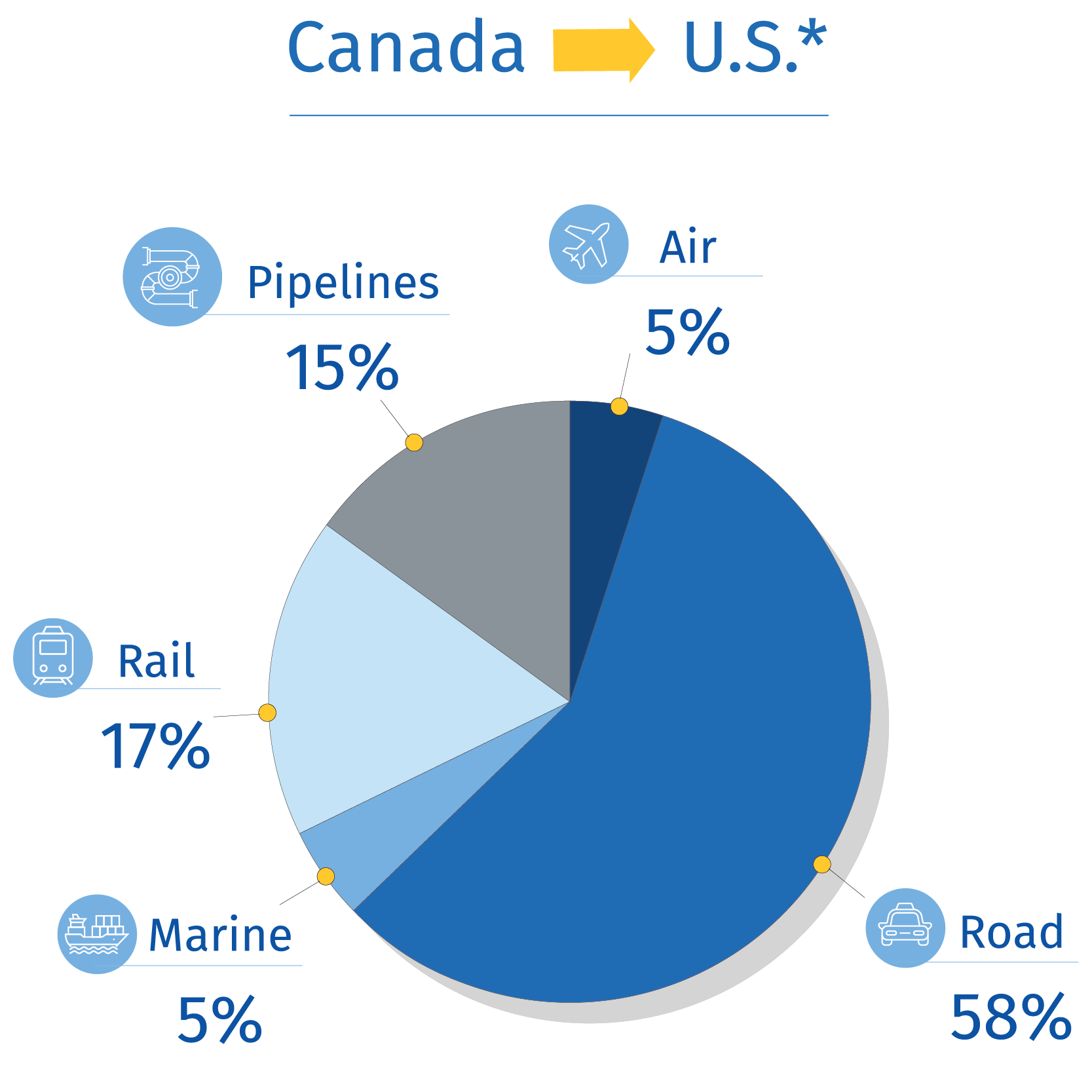

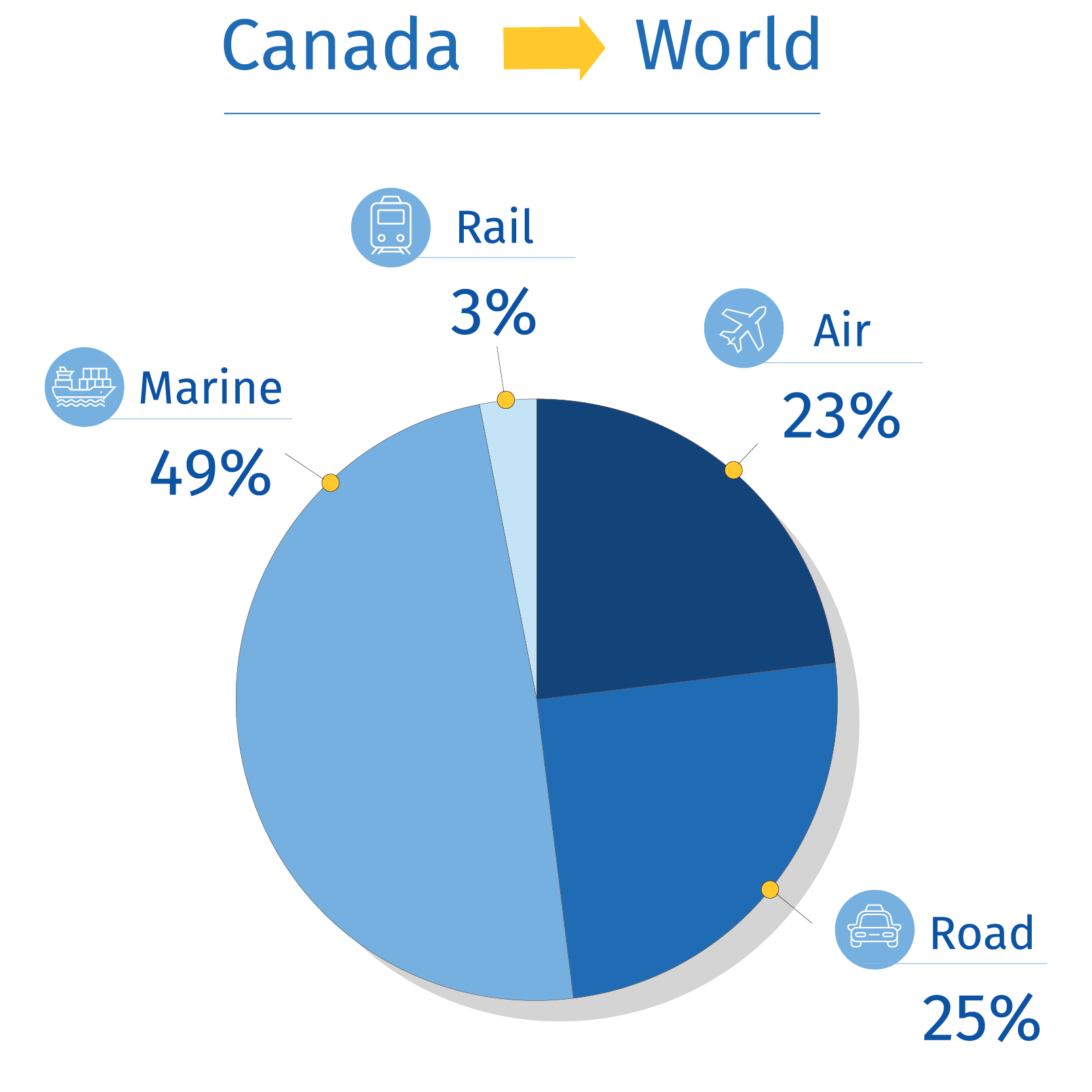

Share of merchandise trade

*63% of total Canadian merchandise trade

Source: Statistics Canada

Stronger: Boost investment by $600 billion+ to build resilience

Years of operating global supply chains on a razor’s edge ignored the long-term costs of major system interruptions. The recent strike at B.C. ports has laid bare our vulnerabilities; billions of dollars in disrupted mining and manufacturing exports will take weeks to clear once even a few days of job action ends.

Jolted by interruptions such as pandemics, geopolitics and climate disasters, the industry has woken up to the risks looming over a transportation sector already straining to keep up with economic and population growth. The reaction: trade flows are shifting to trusted suppliers and transparency is being demanded around suppliers’ contingency plans, Indigenous and community engagement, and plans for addressing the industry’s emissions footprint.

Logistics interruptions are not new in Canada, with no fewer than thirteen real or potentially major interruptions in the past six years. Each has complex causes but represents an ‘own goal,’ sowing doubt about the Canadian proposition at a time when global factors are already providing plenty of uncertainty and the returns to being a bastion of stability are much higher. Canada must do something.

The rub: it will take a lot of money and Canada already lags in transportation investment.

Investment in physical transportation infrastructure (outside pipelines) has picked up in the last few years, especially in marine and rail, but it is barely outpacing economic growth. In some sectors, there are also sizeable investment deficits: seaport engineering investment per megaton of cargo handled averaged 55% below early 1990 levels for 20 years before its recent recovery.

It will take at least another $600 billion in real investment by 2040 from private and public sources just to keep pace with economic growth. Seizing new export opportunities and making supply chains more resilient, including to the effects of climate change, will require significantly more.

Removing roadblocks

The sector is alive to the challenge. The federal government will continue to support priority projects through the $4.6 billion, 11-year National Trade Corridor Fund until 2028. The recently released National Adaptation Strategy identified transportation among sectors at high risk of interruption and committed concrete actions and funding.Most of the investment will nonetheless fall to the private sector and provinces. Federal funding has been impactful, but small relative to the $39 billion per year in annual investment in physical infrastructure. The public sector, mostly provinces, is responsible for 94% of investment in roads, but just 25% in other transport infrastructure.

Limited financing models continue to stand in the way. Air and maritime port authorities–arm’s-length federal lessors, developers, and regulators of Canada’s most strategic 21 air and 17 marine ports–face restrictions on debt financing.

Both suffered revenue losses during the pandemic and airports took on a lot more debt. Recent federal legislation recognizes the issue but promises only a 3-year review cycle for marine ports. Despite their interest in long-tenor assets, pension funds are not major investors in transportation infrastructure given the absence of clear user-pay revenue streams and other barriers to reaping returns from innovation.

Faster: Collaborate to develop a seamless multi-transport network

Timeliness, cost-competitiveness, and agility are more important than ever. Shaving hours or dollars will change a country’s competitive standing in a world where the need to build resilience risks adding costs for consumers.

Canada has a sophisticated and well-regarded logistics system, with a best-ever #7 ranking in the 2023 World Bank Logistics Performance Index on higher investment rates, improved customs clearance, and other strong inputs to logistics performance. But we still struggle to translate this advantage into best-in-class timely, transparent, and competitively priced movement of goods.

Canada lags peers on costs and efficiencies

Canada’s Logistics Performance Index 2023 rankings

Source: UNCTAD, RBC Economics | *historically high ranking for Canada (across seven LPI reports since 2007)

Canada’s ports have been an area of weakness, ranked last among OECD countries in marine port turnaround times—the time spent loading or unloading a ship.

Similarly, the World Bank’s Container Port Performance Index ranked the Port of Vancouver—Canada’s largest seaport—second last in 2022. Major airports in Toronto and Montreal had the dubious distinction at times in 2022 of being among the lowest ranked of global hubs for flight cancellations and delays.

Canada’s done better in terms of improved average rail car speeds and decreasing wait times for trucks at land border crossings, but it’s not all good news. Railways have long struggled with consistent service standards, and the trucking sector is the epicentre of the labour challenges that have dogged the entire sector. Road and rail freight price growth have outpaced headline inflation, with trucking indices 25% higher in spring 2023 than before the pandemic.

Share workers 55+

All industries: 23%

Transportation and warehousing: 29%Ways to get on track

Logistics is hard in Canada with its vast distances, diverse products, sparse population and cross-country trade imbalances. Optimizing a rather linear network naturally prone to more disruption means Canada must be relentlessly efficient.

Investments in new capacity and transportation nodes are key, but collaboration across the sector will also produce major gains. Participants have incentives to optimize only their piece of the supply chain, sometimes to the detriment of the system. Any one shipment could touch three or four transport links, such as trucks, warehouses and rail. To maximize asset utilization, national rail companies may refrain from moving cargoes further inland if warehousing capacity continues to be an issue in Toronto or Calgary. Labour unions operating under short term contracts may fail to embrace the benefits of technological transformation. Meanwhile, risk averse regulators can significantly extend project approval timelines, triggering a domino effect with ripples across the supply chain.

Transparency, cooperation, and long-term planning would be a new way of operating but this shift in mindset can set Canada ahead. Industry and government are calling for new cooperative approaches. The federal budget announced a permanent national supply chain office and initiatives to harmonize data and improve governance. The question is whether they will go far enough to produce systemic change for businesses to seize the opportunities at Canada’s doorstep.

Smarter: Embrace AI to transform logistics

Canada’s supply chain needs to get stronger and faster without breaking the bank. So, it needs to get smarter. Global trade is shifting but unpredictable: better rail and road infrastructure will help in facilitating increasingly U.S.-centric supply chains, but how much focus should Canada dedicate to marine and air facilities to diversify our opportunities?

Hard infrastructure can take over a decade to build, and redundancy or obsolescence is costly. Improving performance and flexibility today through agile investments in data, technology and process improvements will have long term benefits no matter the shape of global trade.

Canadian businesses have a long-standing pattern of underinvesting in software relative to global peers, leading to corporate data environments that are not equipped to integrate artificial intelligence (AI). Canada’s transport sector has had a deficit in software investment per volume of good trade versus the US since 2013.

AI is set to transform transportation and logistics, optimizing areas such as route planning, shipping volumes, predictive maintenance, safety monitoring, and customs inspections. Informed by solid, comprehensive data, it can improve productivity and resilience. Optimizing trucking routes, for example, reduces fuel costs and emissions, while allowing efficient re-routing in the case of emergency.

It’s seeing this type of value-add that should convince businesses to invest in collaborative approaches. The value of AI is not in one hand or application, but investment in a system capability that begets new opportunities and heathy competitive tensions. But until this value proposition is understood, and data capabilities improved, participants may just see the cybersecurity, competitive, and regulatory risks.

Investment in hard assets

Hard technology and process improvements are also needed. North American ports are behind their European and Asian counterparts in automation of port operations. Australia has automated trains while Singapore boasts an automated dock that saves time and labour hours. Equipment that allows grain to be loaded onto shipping containers in the rain—an operation that is otherwise paused in rainy B.C. leading to 30-40 days of lost productivity per year at grain terminals1—is in operation at other global ports. Larger transport containers or rail loop tracks for grain loading could also enhance efficiency across the supply chain.

Finally, a smarter supply chain is also about integrated strategy. A critical minerals blueprint that does not factor in sufficient maritime transport to global markets will see Canada resigned to sending bulk commodities to the U.S. instead of attracting higher-value processing activity. Without seamless trade ties, Canada’s Indo-Pacific strategy will lack teeth.

Aligning priority transportation infrastructure investments to support industrial, trade, climate and regional development priorities is key. The federal government is engaged, moving forward with strategies, supply chain visibility initiatives, and governance changes to break through barriers, but progress has been slow and piecemeal.

Ideas for action

Outline a long-term transportation infrastructure investment strategy. Building on the National Supply Chain Task Force, the federal and provincial governments should produce an integrated long-term national investment strategy with clear funding measures and targets for industries. The plan must be integrated with industrial, trade, regional, and climate strategies.

Outline a long-term transportation infrastructure investment strategy. Building on the National Supply Chain Task Force, the federal and provincial governments should produce an integrated long-term national investment strategy with clear funding measures and targets for industries. The plan must be integrated with industrial, trade, regional, and climate strategies. Accelerate data initiatives. Public and private data initiatives in progress need to move with urgency, incorporate more transportation sectors/activities and transport hubs, and support better public, historical, and global benchmarking data. Industry should partner with tech companies and research organizations to transform their data competencies.

Accelerate data initiatives. Public and private data initiatives in progress need to move with urgency, incorporate more transportation sectors/activities and transport hubs, and support better public, historical, and global benchmarking data. Industry should partner with tech companies and research organizations to transform their data competencies. Improve industry, union and government dialogues. Regional transportation hubs should convene regular discussions among all stakeholders, such as the Port Forward strategic planning exercise led by the Port of Vancouver, to bolster effective working relationships.

Improve industry, union and government dialogues. Regional transportation hubs should convene regular discussions among all stakeholders, such as the Port Forward strategic planning exercise led by the Port of Vancouver, to bolster effective working relationships. Experiment with technology. Industry and unions must forge a new cooperative relationship to develop a long-term plan to integrate technology in infrastructure, while respecting worker safety and fair job transitions. Regulators need to be more active partners in industry innovation. Adopting technologies in limited or test applications can help better illuminate policy considerations. Government funding can support trial initiatives or transformative technology investments at smaller firms.

Experiment with technology. Industry and unions must forge a new cooperative relationship to develop a long-term plan to integrate technology in infrastructure, while respecting worker safety and fair job transitions. Regulators need to be more active partners in industry innovation. Adopting technologies in limited or test applications can help better illuminate policy considerations. Government funding can support trial initiatives or transformative technology investments at smaller firms. Explore the role of an independent system operator. A transparent, accountable, and apolitical system operator with the information to resolve supply chain logjams in the national interest could reduce disruptions and inefficiencies. Governments and industry should ensure that governance models and incentives of various actors align with a smooth-running network.

Explore the role of an independent system operator. A transparent, accountable, and apolitical system operator with the information to resolve supply chain logjams in the national interest could reduce disruptions and inefficiencies. Governments and industry should ensure that governance models and incentives of various actors align with a smooth-running network. Pursue new revenue models. The Canada Infrastructure Bank and provinces should continue to explore areas where user-pay financing models will improve the efficiency, cost, and emissions of public use infrastructure. Ottawa should be proactive in re-evaluating the debt capacity of air and maritime port authorities to enable long-term planning and investment.

Pursue new revenue models. The Canada Infrastructure Bank and provinces should continue to explore areas where user-pay financing models will improve the efficiency, cost, and emissions of public use infrastructure. Ottawa should be proactive in re-evaluating the debt capacity of air and maritime port authorities to enable long-term planning and investment. Invest in workers. Recruit and retain transport workers to alleviate shortages. Government must fast-track immigration programs, and industry should commit to job flexibilities, training and skills upgrading to reduce high attrition rates.

Invest in workers. Recruit and retain transport workers to alleviate shortages. Government must fast-track immigration programs, and industry should commit to job flexibilities, training and skills upgrading to reduce high attrition rates. Streamline flow of people and goods across international and interprovincial borders. Federal and provincial governments should continue to pursue efficient customs clearings and inspections, harmonization of regulations and credentials, and free trade/ data exchange agreements.

Streamline flow of people and goods across international and interprovincial borders. Federal and provincial governments should continue to pursue efficient customs clearings and inspections, harmonization of regulations and credentials, and free trade/ data exchange agreements.

Download the Report

Contributors:

Cynthia Leach, Assistant Chief Economist

Josh Nye, Senior Economist

Yadullah Hussain, Managing Editor, Climate & Energy, RBC Thought Leadership

Shiplu Talukder, Digital Publishing Specialist

Caprice Biasoni, Graphic Design Specialist

Darren Chow, Senior Manager, Digital DesignThis article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More