We spent months talking to experts about why creativity is a competitive advantage. Throughout this report, you’ll hear from them directly.

The new “it” skill

Welcome to the Soaring ‘20s, where creativity is the new “it” skill.

As Canada emerges from the COVID-19 crisis and enters a “two-dose summer,” we’re coming back together in workplaces, coffee shops and restaurant patios. There’s a palpable excitement in the air, and an opportunity: to harness this energy to rethink and rebuild in a new era of creativity.

The pandemic transformed the economy and disrupted every aspect of our lives. It also unleashed a remarkable wave of creativity.

If you peeked into the windows of Winnipeg’s Chaeban Ice Cream during the lockdown, you might have spotted owner Joseph Chaeban finally pursuing his childhood dream of making cheese. He’s now selling his artisanal creations to local restaurants, bakeries and grocery stores.

When sports stadiums went quiet, teenage entrepreneur Elias Andersen launched a new generation of audio technology from Thornbury, Ontario. Hear Me Cheer takes microphones in fans’ mobile devices and creates a real-time crowd atmosphere that’s been used in college football games and Major League Soccer.

Creativity is rising to the top, and not just in the usual places, like the arts or science and technology. We’re already seeing that between the first quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, employers began asking for more creative competencies in job postings, like critical thinking (up 37%) and flexibility (up 20%). The spike is particularly notable in healthcare, education, and sales and service—fields that were deeply impacted, and likely forever changed, by the pandemic.

“There is no commerce without creativity.”

—Daniel Lamarre, CEO of Cirque du Soleil

Every corner of our economy, from construction to retail, should be seen as a place for creativity to grow. If you think some sectors are too traditional to change—reconsider. Just look at how the agriculture sector has responded to the uncertainties of climate change, global trade spats and labour shortages: with vertical farming, where food grows in warehouses near city centres.

Now that people are once again gathering and mingling—the jet-fuel of creativity—this next decade is a prime time for creativity to flourish. The pandemic has shifted power to individuals, who can take advantage of an increasingly decentralized economy to work, shop, watch and learn from anywhere. Large cities, secondary centres and online platforms are suddenly on equal footing. There’s never been a better time to take a new idea and run with it.

Read more from our conversation with Richard Florida.

The world was already on the cusp of a new creative era when the pandemic erupted. The key elements of the Fourth Industrial Revolution—automation and digitization—sparked an unprecedented opportunity to create. Individuals were free to take more risks, and businesses were more open to diverse ways of thinking and doing. Virtual reality, self-driving cars and remote surgery—all once the domain of science-fiction—were shepherded into reality.

LinkedIn data from more than 600 million

professionals and 20 million jobs revealed creativity

was the skill most in demand in 2019 and 2020.

professionals and 20 million jobs revealed creativity

was the skill most in demand in 2019 and 2020.

Through our research, we are increasingly convinced that creativity is going to be a critical skill through the 2020s, as we re-emerge, re-build and re-invent, delivering ideas at a rate never seen before right across Canada.

The pandemic showed us that business doesn’t always proceed as usual. At the organizational level, firms are experiencing significant turnover. People are returning to different workplaces: either new ones, or ones that have radically changed since March 2020. It’s a unique moment in time, and it could slip away.

In this report, we talk with some of the most creative thinkers in Canada—business leaders, entrepreneurs, educators and artists—about Canada’s creative potential. We explore the growing demand for creative skills in key sectors of Canada’s economy, how different creative types deliver value—often in unexpected ways—and what actions should be taken to translate our country’s creativity into economic growth over the next decade.

There’s no time to waste, as we seek to solve some of the greatest challenges of our time: rebuilding downtowns, reimagining the delivery of healthcare and education, and tackling the climate crisis.

In Humans Wanted, a landmark 2018 report by RBC Thought Leadership and Economics, we examined how technology was disrupting the Canadian workforce, and identified the skills required for the jobs of the future.

The rise of artificial intelligence and automation mean routine and repetitive work is the most at-risk of disappearing, and even work in unexpected fields will be transformed. Our research showed the most highly valued skills are those not easily replicated by a machine—higher-function, cognitive activities from active listening to critical thinking and complex problem solving. Demand for these human, creative skills will only grow stronger.

Crisis drives creativity

This won’t be the first time crisis drives creativity. It’s a pattern that emerges when we look at the arc of human history.

Some of the greatest leaps in human achievement immediately followed periods of devastating crisis, after mass disruption opened the door to new leaders and new ideas. One example: the Renaissance after the Black Death. Another: the Roaring ’20s, after the First World War and the Spanish flu pandemic. Amid the crisis, people gained a better understanding of the most pressing issues that needed addressing. In the aftermath, those who had adapted to the changed circumstances had the opportunity to introduce new ways of doing things to an audience willing to listen.

Crisis drives creativity

Throughout history, pandemics have thrown society into crisis, disrupting the old way of doing things. Rather than returning to the status quo, the post-pandemic age is characterized by a radical rethink and a shift in power and resources.

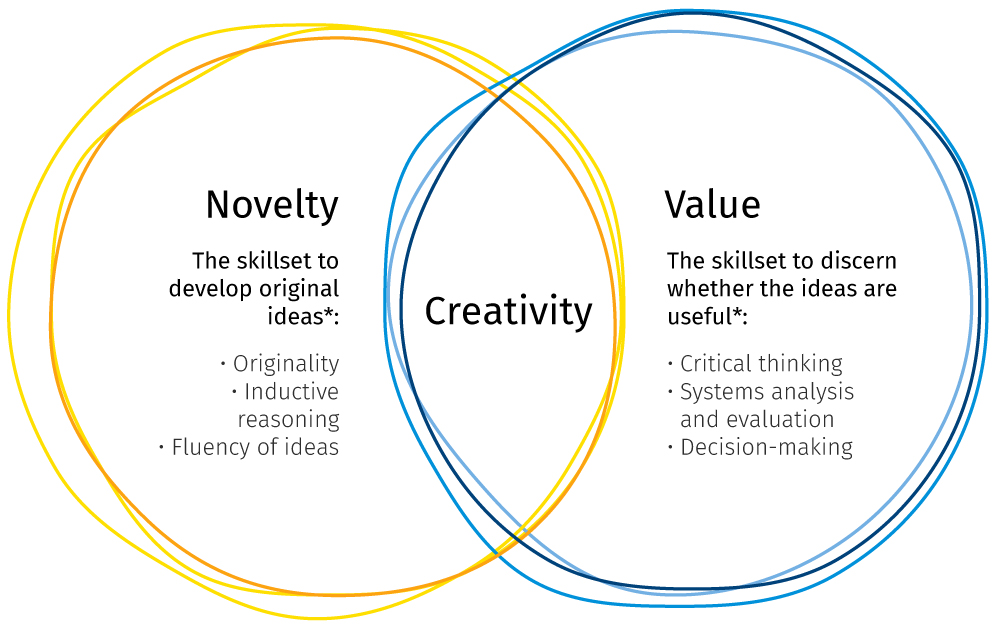

Creativity = novelty + value

We’ve shown how creativity can thrive after crisis, and why the conditions are right for it to kick-start Canada’s COVID recovery. The next challenge is to better understand what creativity is, and how to nurture it in young people and across our country’s workforce.

Creativity, in our framework, delivers both novelty and value.

Creativity is an amalgam of skills and abilities that allows us to conceive novel and useful ideas. We’ve seen that through the pandemic, whether it’s healthcare workers or teachers or creative artists, all connecting with people in difficult circumstances, in different and ultimately creative ways.

When learning moved online, Ontario grade three French teacher Steve Massa decided to get creative to keep his students engaged from their kitchen tables. He launched a YouTube channel under the name Monsieur Steve, and took students on virtual field trips around Toronto and as far away as Thunder Bay, incorporating costumes and puppets and his pet cat all in the name of making French grammar fun.

“We have a great need for imagination and creativity to solve the grand challenges—whether these are social problems or healthcare or new technologies. We need creative minds and creative actors to make the world a better place.”

—Dr. Sara Diamond, President Emerita of OCAD University

While we often associate creativity with individuals, organizations, cities and even countries can be creative too. In action, it can mean taking a process from one industry and adapting it to another, like when the U.S. Army studied the logistical and planning methods of the Barnum & Bailey Circus. It can also take the form of coming up with new and practical uses for existing products, like when Nike co-founder Bill Bowerman used a waffle iron to mold a new urethane sole for running shoes.

Increasingly, creativity is acknowledged as a critical economic variable: a competency that can make an individual stand out in his or her field, or that enables a company to dominate, or even create, an industry. If exercised on a larger scale, it can give a society or economy outsized impact on the broader world.

Creativity is bolstered by certain mindsets, and an openness to new perspectives is one of the most important. There is a clear opportunity here for Canada, a country of immigrants, to step up to the plate and get creative.

If we can harness that kind of ambition as a country, Canada—the energy power—could become a creative energy power with ideas that fuel the world.

Most Canadian youth feel confident in their creative skills, but not as much as they do for other 21st century skills.

A survey of 15,000 RBC Future Launch participants found two-thirds (65%) of 15- to 29-year-olds have a high degree of confidence in their creative skills for the workplace. The groundwork for even more creativity is there: they are more comfortable thinking critically (74%), collaborating (73%) and problem solving (70%) than being creative.

Notably, young women have a high degree of confidence to “brainstorm in groups” (74%) compared to young men (64%). Youth not in education or employment (40%) have the lowest comfort in “thinking outside the box.”

This show us that injecting creativity into education specifically would have an outsized impact on the rest of Canada’s key sectors.

Read more from our conversation with Josie Fung.

A creative boom in Canada’s labour market

Nothing looks quite the same after COVID-19, and that includes the job market. According to our analysis, 21% of Canadians work in roles that require high creative-thinking skills. But that’s now ticking upward, as our appetite for creativity grows.

We’re seeing a greater demand for skills and tools that feed creativity across the labour market. Between the first quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, employers asked for more creative competencies in job postings, including:

- Critical thinking, up 37%

- Flexibility, up 20%

- Teamwork, up 18%

- Ability to learn, up 15%

- Continuous improvement, up 12%

- Problem solving, up 9%

- Strategic thinking, up 8%

Three Canadian sectors in particular are demanding more creativity among new hires: healthcare, education, and sales and service. These sectors have been among the most affected by COVID and are undergoing large-scale transformations that will need creative workers at their core.

- Healthcare: Job postings among health occupations are up 36% since February 2020, as demand has spiked for frontline workers and those who can help coordinate Canada’s public health response. Job postings that list creative skills are up 125%, as roles such as healthcare managers (up 79% in Q1 2021) and health diagnostics (up 67% in Q3 2020) need more problem solving, critical thinking and strategic planning to counter the spread of COVID-19.

- Education: Job postings in the education field are up 39% since February 2020. Those requiring creative skills spiked by 50% in September 2020 and again by 30% in January 2021, reflecting educators’ need for fresh ideas as new restrictions took hold and online learning expanded. Demand for school administrators has jumped (up 167% in Q1 2021), while education policy and program development roles have grown (up 11% in Q3 2020), with needs for adaptability and continuous improvement driving demand for creative candidates.

- Sales and service: Retail job postings overall tumbled during lockdown periods. However, postings explicitly seeking creativity in sales and service increased during these periods, by 14% in April 2020 and 20% in January 2021. Businesses appear to have sought out these skills to help develop new shopping and service models during disruption. Doing things differently was reflected in high growth jobs, including services supervisors (up 24% in Q3 2020) and retail and wholesale buyers (up 18% in Q1 2021), seeking more originality, analytical skills and those with the ability to learn.

In the short term, this means people with high creative skills will enjoy greater mobility and choice of roles. Over the longer term, more Canadians will develop creative skills as workplaces give higher priority to original ideas and critical thought.

Creativity will increasingly be a competitive advantage for individuals, for firms, and even for the country as a whole.

Tomorrow’s creative leaders

There’s only one Elon Musk—and that’s quite all right.

When we think of creative individuals, we often conjure up historic visionaries and inventors, but creativity lives in all of us. It just takes on different forms: in the studio, the laboratory, the classroom and the boardroom.

Through our research, we’ve identified four broad creative archetypes that play different but crucial roles in our society.

The Visionary

This is the Elon Musk category. The Visionary imagines new markets and is willing to take huge risks to bring about change in the world. They build loyal followings, even beyond their own industry, influencing consumer tastes and preferences. The way electric cars have sped from obscurity, to cool, to the dominant trend in the auto industry? That’s the Visionary touch.

The Instigator

This is the sector-specific superhero. The Instigator is able to identify gaps, combine ideas and see opportunities others do not. They can create wholly new products or service offerings, disrupting the sector where they operate. One such example: Canadian tech titan Michele Romanow, whose startup Clearco disrupted the lending market and is now the world’s biggest ecommerce investor.

The Thinker

Drill down a little deeper, and within every workplace, you’ll find the Thinker. This is someone who stands out for their critical thinking, and their adeptness at identifying challenges and coming up with novel ways to address them. In the 1990s, University of Pennsylvania biochemist Katalin Karikó devoted herself to an obscure field: mRNA research. Decades later, her discoveries led to the groundbreaking Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, and turned the tide on COVID.

The Hustler

Need someone to see a new idea through to execution? Call a Hustler. They’re critical to analyzing what is possible, and strategically tweaking the lofty ideas and strategies of the Visionaries and the Instigators. Without the action-oriented Hustler, many ideas might never see the light of day. Apple co-founder Steve Jobs is the Visionary behind the iPhone, but the awe-inspiring camera functions in every new model? Those are thanks to Apple’s 600 camera-hardware technology experts.

“Creativity rests on encouraging yourself to think freely outside of the box, and then working diligently to distill, iterate and ultimately prototype, depending on what the process is.”

—Janet Morrison, President of Sheridan College

How to cultivate creativity

Creativity has always been important, but it matters now, maybe more than ever, as Canada looks beyond the pandemic and into some exciting and scary decades ahead, that will test us as a nation.

Over the last few months, we talked to some of Canada’s most creative people about how they cultivate creativity and what others can learn about maximizing creative potential in individuals and organizations.

Here are four key takeaways:

1. Creativity can be nurtured

Creativity comes naturally to some. It can also be nurtured and developed.

Gil Moore, drummer of the rock band Triumph and founder of Metalworks Institute, differentiated between virtuosos—those who have “explosive growth in their talent and a natural repository of creative juice that just flows”—and the rest of us who have to actually work at it through repetition and gaining skills.

Read more from our conversation with Gil Moore.

Creativity is known to thrive in the world-famous animation program at Oakville, Ontario’s Sheridan College, but its president, Janet Morrison, is quick to point out the value of teaching creativity across all disciplines. In the college’s business program, students learn creative problem solving: how to clarify the situation, generate ideas, develop and iterate solutions, and implement plans.

Josie Fung, who is tasked with building “future-ready problem solvers” as the executive director of I-THINK at the Rotman School of Management in Toronto, suggested giving students real-world problems to solve, and then the space to do so.

When Parks Canada asked high schoolers at Toronto’s John Polanyi Collegiate Institute to help solve a problem—how to get more people to come to Rouge National Park—the students skipped over ideas like a poster or ad campaign. Instead, they reframed the question, to think about the role of the park in society. This opened up so many more possibilities. They thought: what if the park could be a place for a drug rehabilitation centre? What if it could be a place for mental health therapy? Four years later, Rouge Park struck up a partnership with Blue Door, a nonprofit that provides emergency housing for those experiencing homelessness and crisis, to provide affordable housing using Parks Canada land.

2. Create a culture that embraces the freedom to fail

Shopify—Canada’s most valuable company—embraces failure. You read that right.

“We have built an environment that allows for risk taking, that allows for curiosity and resourcefulness, that allows for reactions,” said Brittany Forsyth, former Chief Talent Officer.

That kind of environment is key, Forsyth said, because creativity isn’t about a lightbulb moment. It’s about coming up with lots of ideas, challenging assumptions and connecting dots, until it unlocks something new: the killer idea that separates you from the competition.

“We give permission to do these key things such as experiment, fail, grow. It’s OK to say you were wrong yesterday and you’re right today, to change your mind.”

—Brittany Forsyth, Shopify’s former Chief Talent Officer

Read more from our conversation with Brittany Forsyth.

If you look at Cirque du Soleil, ideas can come from every corner of the organization. You need to give employees the space and encouragement to share them.

“We have 5,000 pairs of eyes and ears and we encourage our people to always feed us with something they discovered,” said Daniel Lamarre, the Quebec-based company’s CEO. “Sometimes it might be by reading a book, seeing a new movie and hearing a new piece of music or just seeing something on YouTube or on social media that could be attractive to us.”

Pro tip: Companies can encourage employees to try new things by shaking up the work day, or incorporating such expectations into employee performance goals. Shopify uses “hack days,” where everyone stops what they’re doing and spends three days on a project of their choice, usually coming up with programs or solutions around a specific theme. Over at Google, Gmail was famously created as part of the company’s 20% rule, which allows employees to spend 20% of their time exploring projects that may not deliver immediate dividends but could become big opportunities in the future.

3. Creativity thrives on strategic constraints

It might sound counterintuitive, but limits can actually spur creativity.

“We thought that if we gave students open rein on creating ideas, that would be the way forward,” said Fung, speaking of her work with I-THINK. “And actually, what we heard is that by giving a little more structure, by giving a few more constraints, it actually helped channel their creativity.”

Creative people are comfortable with ambiguity but are also compelled to make sense of it and add their own structure, according to Tom Waller, Chief Science Officer at Vancouver-based Lululemon.

“We very much look for people that are able to sit in ambiguity and go, ‘Hmm, I’m on a blank sheet of paper here, but I’m just going to start doodling if nothing else. And, oh! This doodle turned into something,’” Waller said.

Read more from our conversation with Tom Waller.

Pro tip: There’s actually a simple three-step way to set up those constraints to drive creativity, according to Ajay Agrawal, head of the University of Toronto’s Creative Destruction Lab. Step one is to establish well-defined goals: what is the problem you’re trying to solve? Step two is ensuring that people have the resources they need, such as time and money, to explore potential solutions. And step three is to recognize and measure success along the way.

4. Creativity is a team sport

The creative engines of the past relied on solo inventors. Leonardo da Vinci, for instance, and other Renaissance thinkers who were polymaths with expertise across multiple areas.

That’s no longer the case, Agrawal said.

“As fields become more and more complex, in order to really understand the frontier of the field, you need to collaborate across multiple people who are experts in different areas.”

“I find that everybody has the potential to play a role in the creative process. It might be a different role, but there is a role for everybody in the creative process.”

—Ajay Agrawal, head of the University of Toronto’s Creative Destruction Lab

Read more from our conversation with Ajay Agrawal.

This brings us back to our point about creative archetypes: you may have a Visionary or Instigator championing the idea, but you’ll also need a Hustler. The key is to identify what roles are required to produce the best outcomes, and how leaders can help develop the right people and skills for those roles. It may mean casting a wide net to find people from diverse backgrounds and ways of life who are able to contribute their experiences and knowledge. Or thinking about what partnerships can be developed with firms in other sectors, and what opportunities can be generated by reaching out to community organizations.

An age of ideas

As we charge forward into the 2020s, Canada faces some epic challenges. The pandemic highlighted all that is not well within our borders: the broken structure of our long-term care homes, the disproportionate childcare burden on women, racial health and economic disparities, and the challenges of coordinating a country-wide response to an emergency. We cannot look away now. Instead, with fresh eyes, we must embrace the new possibilities that have opened up on a mass scale, including telehealth, remote education, and flexible work arrangements—and the new talent that we could draw in. We are in the early stages of a creative transformation of our economy and society. The COVID crisis, like those that have come before it, shattered our assumptions about how the world works and forced society to embrace experiments and reorganize in a new way. By promoting creativity as a key skill within our schools and workplaces in the post-pandemic world, we can shift into an exciting Age of Ideas that tackles Canada’s most pressing problems.

The Creativity Economy

For more insights on how Canada can weave creativity into its culture, listen to our special two-part series of the Disruptors podcast.

About the Authors

Trinh Theresa Do (she goes by Theresa) is responsible for strategy development on the Thought Leadership & Economics team, with occasional forays into podcasting, research, and writing. Previously, she was a strategy advisor to senior management and executives at RBC’s Personal & Commercial Banking business. Prior to joining RBC, Theresa was a national political journalist at CBC News and co-founded a nonprofit that promoted civic engagement through technology innovation.

Sonya Bell joined RBC’s Thought Leadership and Economics team as a Senior Manager, Content Delivery in 2018, coming from Queen’s Park where she was a senior writer to the former Premier of Ontario. Previously, Sonya worked in journalism as a producer at CBC and as a federal political reporter for iPolitics. Between Parliament Hill and Queen’s Park, she spent two seasons as a comedy writer on This Hour Has 22 Minutes.

Andrew Schrumm is a former lead researcher on RBC’s Thought Leadership team, where he examined how Canada can enter the 2020s as a diverse, innovative, and sustainable nation. He managed RBC’s future skills research project on skills-based job mobility, life-long learning, and the potential of automation in our economy.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More