![]()

If 2021 was the year Canada rounded the corner on the pandemic recession, 2022 is the year it can accelerate out of a decades-long pattern of slowing growth.

Though a pandemic recovery is in sight, a slow-growing labour pool and lacklustre record on investment and innovation have set a low speed limit for the economy.

The greener, more digital and tech-enabled society accelerated by COVID-19 has opened new pathways for growth that could ignite spending, investment and innovation. Businesses and households are lined up to propel this change, but their efforts are likely to be hampered by near and long-standing obstacles.

As it starts its new mandate, the federal government can help set a new course. Growth-oriented federal and provincial government policies can be the foundation for the increased private investment needed to boost Canada’s growth trajectory.

Other countries are already remaking their economies in a bid to reverse the secular trend of low and declining economic growth rates. Canada does not want to be left behind. With a skilled workforce, strong record as a tech and energy innovator, and investment opportunities, it doesn’t have to be.

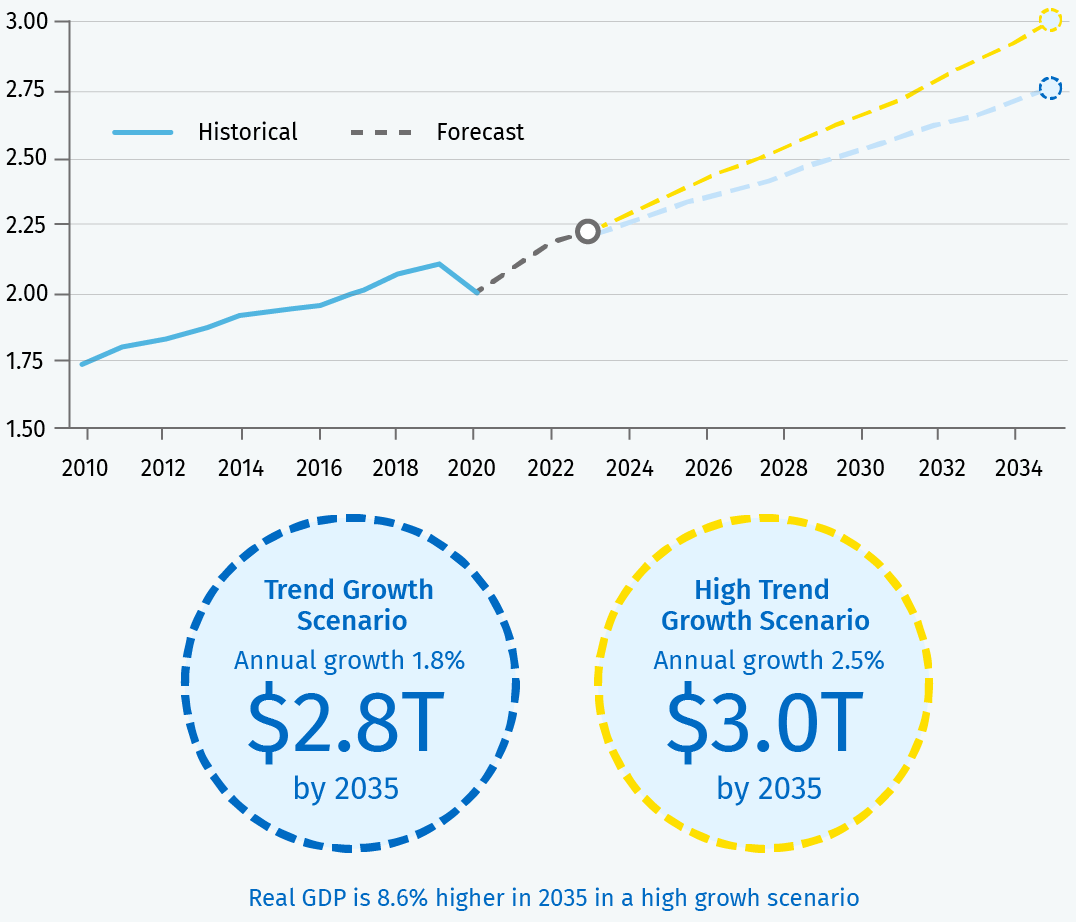

Two scenarios for Canada’s real GDP growth

$ Trillions

Source: Statistics Canada, Haver, RBC Economics

A 6 point plan for growth

1. Embrace new approaches to innovation policy

2. Forward-looking policy, public infrastructure and blended finance for climate action

3. Promote services trade and Canadian platforms; protect intellectual property and data

4. Increase competitiveness with tax, competition, and regulatory policy

5. Attract, develop and retain new sources of talent

6. Education and labour market policy for lifelong learning

Back to the starting line

GDP remains down compared to pre-pandemic levels, due to some particularly weak sectors. But many areas of the economy have already recovered or surpassed pre-pandemic levels. A mix of consumer spending approaching pre-pandemic levels, strong investment intentions, billions in business and household savings, and a supportive external environment will help fuel the ongoing recovery in 2022, even as firms continue to struggle with supply chain disruptions and a labour crunch. RBC forecasts growth of 4.7% in 2021, declining to 4.3% in 2022 and 2.6% in 2023 as it converges to its long-term trend1.

With the end of the recovery—or cyclical growth—nearly upon us, we face a new question. Following the once in a century shock of the pandemic, how can we build more robust growth into Canada’s economy?

Trend growth – or potential growth – reflects the long-run sustainable productive capacity of the economy. Actual growth fluctuates around this trend due to short run ‘cyclical’ factors. Trend growth is estimated based on trend labour supply growth and productivity.

Over five decades, the country’s growth has been anything but dynamic. Real economic growth rates fell from an average of 4.1% in the 1970s to 2.1% between 2010 and 2019. Should we carry on our existing course, we expect a return to a sluggish trend growth of around 1.8% per year beyond 2023, a record reflective of slow labour force growth and muted productivity.

Canada isn’t alone. Many other advanced economies have experienced the same deceleration, attributed to a greying population, the slowing pace of innovation, and in some cases, post-recessionary economic scarring. The trend has been stubborn, suggesting that underlying structural issues will continue to be a powerful force now and into the future.

A new set of starting blocks

The next decade can be different. But if Canada is to secure a new growth trajectory, the private sector must take the lead. With an increase of $200 billion in the value of liquid assets since the start of the pandemic—and with long-term interest rates still low—corporate Canada has the muscle to do it.

There’s a business case for investment. Consumer surveys show a continued desire to engage with e-commerce. Canadians want to shop in a responsible way that favours local businesses and respects the climate and how employees are treated. And intensifying labour shortages provide a good reason to make production more efficient through new investments in automation and equipment.

Businesses’ investment intentions are up in recent surveys, with a majority saying capital expenditures over the next two to three years will be higher than before the pandemic. Many are focusing on digital investments2.

It’s still too early to see a surge in business investment, but early evidence is encouraging: machinery and equipment (M&E) investment is above 2019 levels (excluding transportation equipment). Investments in research and development (R&D) and software are up, too. Trade data show a recovery in industrial machinery imports and a rise in imports of electronic and electrical equipment.

Increased digitization and automation should boost productivity, data and product development. And digitization—together with a greying population that tends to consume more services—can create opportunities for expanded services trade. Investment is needed for decarbonization, mitigation, and development of new green technologies. These same shifts in the global economy can bring opportunities for Canadian firms to export products and expertise, earning global incomes that can help fund the domestic adjustment to the new economy—one with greater spending, investment, innovation and growth.

Getting there will mean tackling new economy challenges, including changing sources of economic value that risk capital obsolescence and loss of competitiveness. It will mean responding to shifts in skills and jobs that threaten displaced workers, and inequality. It will also mean reckoning with where we have not performed well in the past.

Switching leads: Confronting a poor record on business investment and innovation

To achieve a materially different growth outlook, Canada needs to see a big shift in actual business investment and innovation.

Canada has a longstanding investment gap with peer economies. The C.D. Howe Institute finds that Canadian non-residential business investment per worker has lagged behind the U.S. since at least 1991 with the gap widening through the 90s, the mid-2010s and then again during the pandemic. By the second quarter of 2021, Canadian businesses invested 50 cents per worker for every dollar in the U.S3.

The driver of Canada’s mid-decade underperformance was investment declines in the oil and gas sector shortly after the 2014 oil price shock. This investment, which is concentrated in non-residential structures, fell about 60% from its peak prior to the pandemic and remains weak. For the rest of the economy, the Canada-US investment gap stayed relatively stable, but the absolute gap is particularly high.

Canada has also seen a widening investment gap with the U.S. in machinery and equipment (M&E) and intellectual property (IP), driven in part by the oil and gas sector, but also weak M&E investment in other sectors. Investment in both M&E and IP stopped growing as a share of the economy after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC).

Canada has seen a declining GDP share of business investment in research and development, in contrast to many other OECD economies that have seen growing shares.

Given the lag in business investment, it’s not surprising that Canada has a labour productivity gap with the U.S. While the gap narrowed slightly post-GFC, by 2019, Canada produced just 74 cents per hour worked for every $1 in the U.S.

Meantime, lagging innovation could soon present an even greater problem. As technology advances, more economic value will be encapsulated in data, algorithms, brands, digital services and other ‘intangible assets’. With these assets being more scalable compared to tangible inputs like physical capital and labour, delivering large gains to its developers and owners, economic prosperity will increasingly depend on our transition to an innovation economy. And while innovation and competitiveness are influenced by many factors, from policy and demographics to the external environment, business investment is essential.

To varying degrees, Canada performs well in international rankings for entrepreneurial ambition, market sophistication, venture capital financing, institutions, and a skilled workforce. But it ranks poorly in other innovation inputs, with low business R&D investment, low adoption of information communications technology, low per capita scientific activity, an inadequate IP regime, and low openness to competition. And Canada has had trouble translating inputs to innovation outputs. It has middling patent activity, low business creation, and difficulty scaling businesses into global exporters. Firms that are able to export globally are a signal of economic competitiveness, yet net exports have been a drag on economic growth in Canada for much of the past two decades.

The result is imbalanced economic growth. When balanced, growth is derived from multiple sectors of the economy—consumption, investment, and net exports. For Canada, the imbalance between the low growth contribution from net exports and business investment on one side versus high contributions from consumption and housing on the other, means the economy is more exposed to individual economic shocks. For example, a shock to the housing sector could directly reduce economic growth through less construction and sales, and potentially force an abrupt, costly reallocation of resources to other sectors. With climate actions and trade tensions darkening prospects for Canada’s biggest export—crude oil—this imbalance could get worse.

Too much of a good thing? Housing as an economic risk

Low interest rates, strong demand, and constrained supply have led to high housing activity and prices, and elevated household debt. These are frequently discussed as affordability and financial stability issues, but they’re also a direct economic risk. Besides being a source of instability given housing or employment shocks, they may also represent an opportunity cost—significant resources that drive up prices of fixed assets cannot finance other productivity-enhancing investment.

Food for thought: for more than a decade, Canada has ranked in the top three in the OECD for its residential structure share of investment spending. Conversely, Canada’s share of corporate investment has been among the lowest, with share of investment in information and communications technology and intellectual property assets in the bottom half.

New hurdles: Canada’s climate challenge

In addition to long-standing challenges, there are newer obstacles to unleashing spending and investment.

For one, firms that are trying to manage with higher pandemic debt levels, supplier challenges and labour shortages may struggle to plan for the future. Small businesses have historically lagged behind in digital adoption and the pandemic has further burdened seven in 10 of them with additional debt loads averaging $170,0004.

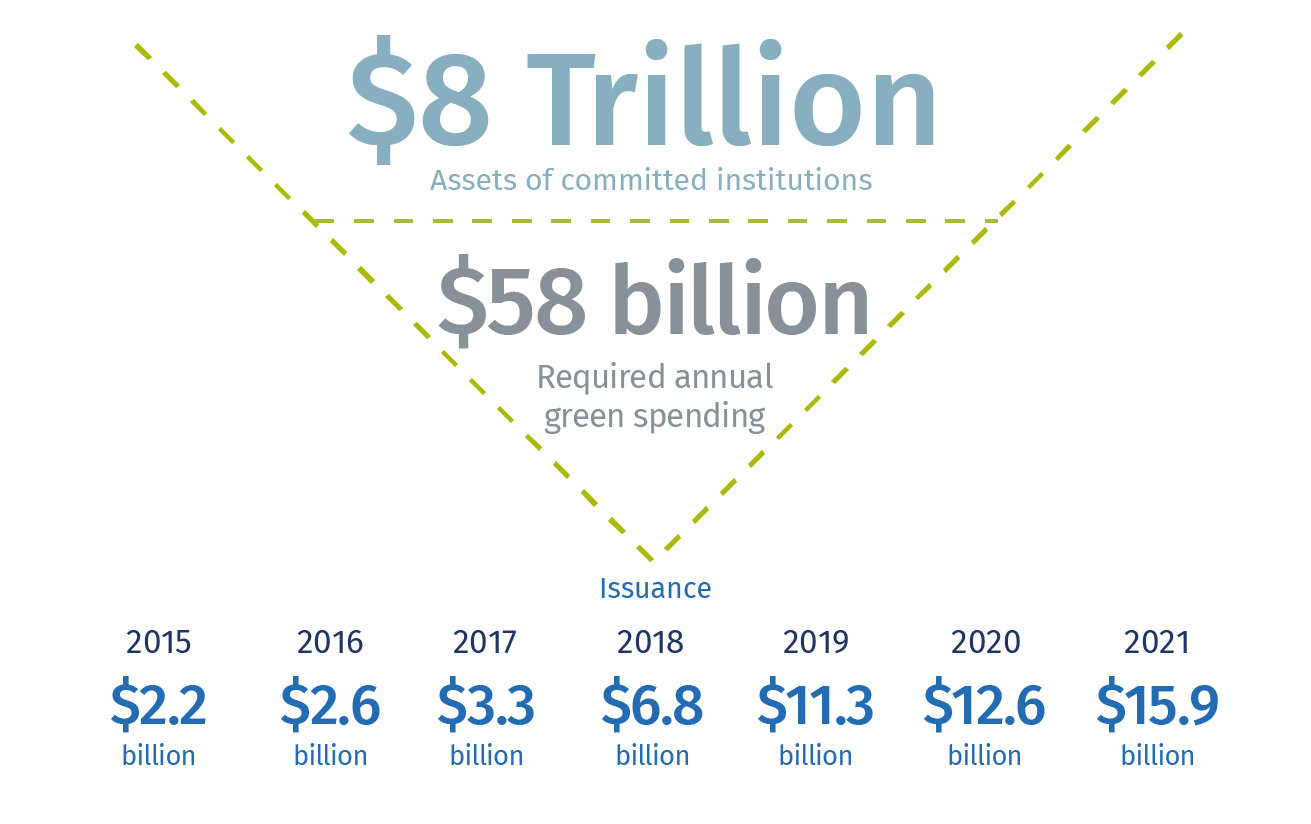

There are also impediments to connecting huge climate funding commitments to green projects. Large Canadian firms with $8 trillion in global assets have committed to Net Zero by 2050, yet spending on green projects is still much lower than the $60 billion per year we estimate that Canada needs to reach5.

Only 6% of Canadian firms plan to measure their environmental footprint over the next year, including less than 25% of large firms with 100+ employees.

And while the pandemic, a lack of financial resources, and clients not willing to pay a higher price are sometimes identified as hurdles to adopting green practices, the majority of businesses identified no challenges6.

Despite growth, green spending is far from what’s needed

Canadian green balance

Source: Bloomberg, RBC Economics | *data to November 1, 2021

The outcome for growth will also depend on supply. If the supply of finance is not a challenge, the availability of some goods may be. As much of the global economy edges toward a green, digital and tech-equipped society, there will be greater demand for the goods that facilitate it—5G networks and cybersecurity systems, critical minerals, batteries, EVs, and renewables. Meeting this demand will take time. Semiconductor factories and lithium mines can take a decade to develop. And the increasingly nationalist agendas pursued by many countries may reduce access to these competitive resources.

Yet it’s another, more localized supply constraint that may pose the most significant challenges.

The lynchpin: Human capital

Canada needs people and skills to reshape the economy. But population ageing and the changing nature of work threaten disruptions in labour markets that could become a significant drag on growth. These are not future problems. The economy was already grappling with labour shortages that have only been accelerated by the COVID-19 crisis. Pandemic-delayed retirements have created a potential wave of workforce exits in the year ahead and immigration levels have still not recovered. This is reflected in a third of businesses reporting labour shortages and a high national job vacancy rate of 6%.

These labour shortages will intensify. Population ageing has led to a declining labour force participation rate, which has subtracted about 1 million people from the workforce since its peak, and represented a drag on economic growth since 2010, when the first baby boomers turned 65.

The participation rate is projected to decline further over the next 15 years and could mean an additional 1.5 million fewer workers over that period, including up to 600,000 over the next three years.

Higher government immigration targets, if met, would address the pandemic immigration shortfall and help boost the number of available workers. But it won’t be enough. To keep the age structure of the population constant at 2020 levels, the annual immigration targets would have to double.

Getting everyone in the race: Canada must tap its rich supply of human capital

Large pools of talent remain underutilized in Canada. Closing the women’s participation rate gap would add another 1.2 million people to the labour force. And other segments of the labour force have been underemployed relative to their credentials. Closing the visible minority earnings could lift GDP by nearly $30 billion per year7, and while not additive because of overlapping populations, closing the immigrant employment and wage gap has the potential to add $50 billion per year in GDP. Indigenous Canadians are also a significant source of untapped potential8, particularly given they are the fastest growing youth population.

Having the right number of workers is key, but skills are just as important. If graduating youth are equipped with new skills and starting in new fields, the impact of potential displaced workers could be minimized. But some educational programs are not keeping pace with change, access to work integrated learning can be uneven, and young people can struggle to get hold of the information they need to make career choices. Despite greater demands, post-secondary institutions face a constrained funding model with tuition freezes and reliance on high-paying international students.

Mid-career workers face different challenges. While tight labour markets should incentivize more business spending on employee training, low wage workers whose jobs are more likely to be affected by automation, and who could benefit the most from upskilling, are also the least likely to participate in it.

Competing for the workforce of the future

A skilled labour force, world-class educational institutions, and an open immigration system give Canada an edge in the global race for talent. But Canada is not the only country struggling with an aging population. Other countries are also looking for highly-skilled immigrants to build their clean and knowledge-based economies.

International firms are using new remote work options to recruit international tech talent. Amazon, Google, Microsoft and Netflix have made plans to aggressively recruit in Canada this year. And while resident Canadians earning Silicon Valley wages may be good for the local economy, it could also be a growth-limiter for Canadian firms if they cannot compete in the international skilled labour market.

Canada’s high housing prices could be a challenge: about 60% of Canada’s permanent residents end up in Toronto, Vancouver, or Montreal, yet two out of three of these cities have among the highest housing costs in the world measured against median incomes9. House prices are even challenging for higher-earning workers. Remote work may help with this, but knowledge-based workers may still be drawn to cities.

Setting the course: The government needs a growth-oriented agenda

To avoid missing out on investment, innovation and talent, Canada must take a closer look at the overall policy framework. Specifically, structural policy—tax, regulation, competition, infrastructure, education, innovation, and trade policy—must work in concert with sectoral strategies and government spending programs to address the challenges before us.

Governments have spent a lot on income support and other programs since the start of the pandemic—an estimated additional ~$400 billion in program expenses over two years (a 50% increase) just at the federal level—preventing long-term scarring to labour markets and balance sheets. Now, their focus has turned to ‘recovery funding’ directed at still-struggling sectors and a range of economic and social issues. Some of this isn’t temporary. Governments have introduced major structural spending programs and, at least at the federal level, signs are any ‘fiscal space’ will be used to expand spending.

This doesn’t need to be a bad thing for economic growth. Social infrastructure like health care, community services and public housing enable individuals to participate in the economy. The pandemic helped shift the policy lens to varying health and economic outcomes, including longstanding equity gaps. Inequality, particularly at high levels, can impede economic growth through insufficient human capital development, weaker consumption or political instability.

And, there is greater recognition that more expansive fiscal policy could be important to breaking free from a low growth economy. Many economists believe that inadequate government spending held back the post-GFC recoveries in the U.S. and Europe. Given the relatively sanguine attitude of bond markets to high government deficits in advanced economies, and low interest rates, governments seem to have more fiscal firepower than they previously thought. Several global economies are experimenting with higher levels of deficit-financed public spending to spur spending, investment and growth.

But these relationships aren’t guaranteed, especially if social spending only finances current consumption, doesn’t target the largest equity gaps, or discourages employment. And financing government programs with a deficit comes with a risk: the new spending might not lead to sufficient economic growth to address future interest rate increases or other economic shocks.

Canada needs a focused, growth-oriented fiscal program to balance these risks. Targeted and forward-looking government policies can be the foundation for increased private investment that tilts Canada’s growth trajectory.

A six-point growth plan

The challenges may be clear, but the solutions are less so. Past policies have struggled to change the course. The increasingly green, knowledge and services-based economy could represent a new growth trajectory for Canada, but it needs a push.

There’s no single policy solution. Canada needs to confront the big challenges of the new economy, like climate policy, IP framework, and skills strategy, and realign the longstanding policy frameworks of the old one, including tax, competition and regulatory policy.

A growth-focused government strategy would encourage increased capital investment in technology and process innovation, helping Canadian firms scale to global markets. It would also enhance outcomes for Canadians in untapped talent pools, promote systems of lifelong learning, and support labour market transitions.

1. Embrace new approaches to innovation policy

Canada’s poor performance on business R&D investment has persisted in spite of above-average government support. Its approach to innovation—providing support through the tax system skewed heavily towards small and medium-sized firms—may be a barrier to innovation output and scale. Meantime, the U.S. and other countries are increasingly pursuing strategies to build economic capacity and compete for geopolitical dominance in new industries.10

Canada should test alternative innovation policies, including providing more support within core programs for larger, growth-oriented firms. More focused, de-politicized and resourced industrial strategies focusing on green and advanced technologies within North American supply chains may de-risk projects and draw private capital. Government procurement and targeted business supports may also accelerate technology adoption.

2. Forward-looking policy, public infrastructure and blended finance for climate action

The gap between green financing commitments and investments—and emissions targets and emissions—reflect a lack of projects with clear financial returns. Given the long time horizon, uncertainty is high around paths to decarbonization and underlying technology costs. Smaller markets for greener products mean firms may not be able to pass on abatement costs to their customers, challenging competitiveness for those that cut emissions.

Governments could prompt more climate action. Carbon pricing should continue to be a key pillar of the plan, rising predictably and applying more broadly. Hard infrastructure like EV-charging networks and carbon pipelines can help make it easier for households and firms to invest in emissions cuts. Canada should push for international cooperation on border carbon adjustments to protect domestic industry while furthering international progress on climate goals. Policy strategies can lay out a clear pathway for individual sectors, from oil and gas to agriculture, and promote blended finance pools of public, private and Indigenous capital for the early stage technologies we may need by 2050.

3. Promote services trade and Canadian platforms; protect intellectual property and data

Canada is a net exporter of R&D services and also a net importer of IP, suggesting Canada is not retaining ownership of its IP and is instead leasing it back from foreign companies. And foreign tech companies are monetizing Canadian data assets. With scalable, intangible assets driving tremendous value, this could be a missed opportunity to drive the scaling of Canadian firms and services exports. A broad range of services, from health care to software to the digital services embedded in the Internet-of-Things, are primed for growth.

Canada needs to consider forging trade agreements that address barriers to expanded global services trade. It needs to review its intellectual property regime to incentivize IP retention and outline data rights. Global platforms should be taxed at the same level as Canadian intermediaries, while multinationals should see time limits on tax benefits, with public money focused on local procurement over employment. Policy can support the development of Canadian platforms featuring local commerce, education and travel.

4. Increase competitiveness with tax, competition, and regulatory policy

Expectations of more public spending are raising concerns over future tax increases and creating uncertainty that may be limiting investment. Canada’s tax system has not been reviewed since 1967, and deviates in important ways from core tax policy principles like efficiency and simplicity. Canada’s low international rank in openness to foreign direct investment could be holding back innovation, while interprovincial trade barriers may be subtracting up to 3.8% from the economy per year. 11

Canada should undertake a tax policy review to streamline tax expenditures, ensure competitive rates of personal taxation (including for international skilled talent), encourage more public-private investment, incentivize re-investment and longer investment horizons, and target tax supports for newer and growth-oriented firms. Regulatory policy, especially in the context of interprovincial trade, also needs attention.

5. Attract, develop and retain new sources of talent

Affordable childcare and flexible working hours have long been identified as major barriers to women’s participation in the workforce. Meantime, challenges in integrating newcomers into labour markets, and opportunity gaps for Indigenous and some visible minority groups, have left other rich sources of workers underutilized.

National child care can have a big impact by targeting the largest affordability and accessibility gaps, while national standards within the early learning system can help expand the next generation of talent. Making the higher annual immigration target of ~1% population permanent, updating special visa programs with a more forward-looking assessment of labour market gaps, recognizing foreign credentials and providing greater pre-arrival labour market support can increase the participation of immigrants. Underrepresented groups should be encouraged to develop new green and digital skills.

And good housing market policy is good labour market policy. Governments of all levels need to coordinate a systematic review of housing policy to address supply-side constraints, rationalize demand-side policies, address inequality, and ensure financial and economic stability.

6. Education and labour market policy for lifelong learning

Despite a relatively high share of adults participating in on-the-job training, Canada has some of the largest participation gaps in the OECD.12 Workers who are highly-skilled, of prime-age (25 to 54 years) and employees of larger firms are most likely to get training.

Canada should explore redesigning income support programs to enable more reskilling while working. Policy makers should update the skills strategy and Canada Training Benefit for green skills and explore national tuition standards to balance access and revenue needs. Provinces should study rapid reskilling programs in various sectors to scale what works, accelerate the incorporation of skilled trades and digital and coding skills into their K-12 curriculums, and provide support for collaborative approaches and common platforms for helping small and medium-sized employers better prepare for their skill and training needs.

1. Central banks weigh inflation, new variant – PDF (contently.com)

2. Business Outlook Survey―Third Quarter of 2021 – Bank of Canada

3. Commentary_606.pdf (cdhowe.org)

4. EN Small Business Debt: The COVID-19 Impact – August 2021 Update (cfib-fcei.ca)

5. The $2 Trillion Transition: Canada’s road to Net Zero (rbc.com)

6. The Daily — Canadian Survey on Business Conditions, third quarter 2021 (statcan.gc.ca)

7. Rebuilding Canada’s labour market: The inclusive recovery imperative – RBC Economics

8. untapped-potential.pdf (rbc.com)

9. Demographia International Housing Affordability – 2021 Edition (fcpp.org)

10. Trading Places: Canada’s place in a changing global economy – RBC Economics

11. The case for liberalizing interprovincial trade in Canada

12. Skills of the Canadian workforce | Workforce Innovation to Foster Positive Learning Environments in Canada | OECD iLibrary (oecd-ilibrary.org

Cynthia helps shape the narratives and research agenda around the RBC Economics and Thought Leadership team’s forward-looking economic and policy analysis. She joined the team in 2020.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More