It's a fact: recessions hit young people and others with less-developed skill sets especially hard.

What’s less well known is that the effects of graduating into a recession last long after the recovery has taken hold. They can have long-term, negative career consequences for those who had the unfortunate timing of starting their careers amid deteriorating economic conditions. Those consequences include slower wage growth and delayed career progression compared with cohorts who graduate in better economic times. With more than 1 million students enrolled in Canadian universities and economists predicting close to a 30% chance of recession over the next 12 months, it’s worth taking a look at the experience of those who entered into the workforce in 2009-2011.

A study of the graduates of the Great Recession indicates that

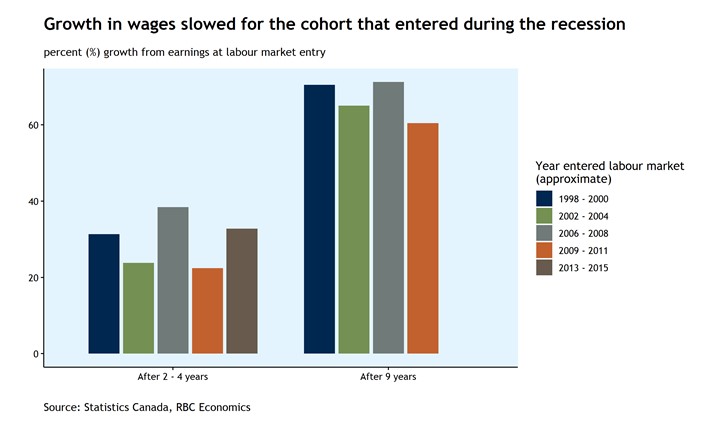

- their wages grew more slowly over the first decade of employment than peers who entered the workforce before the recession

- at age 30-34, they’re less likely to be in a management position than people in that cohort were before the recession

- at age 30-34, they’re less likely to occupy a skilled position than the same pre-recession cohort

Lessons from the Last Recession

In the fourth quarter of 2008, Canada entered its worst slowdown since the 1980s. It would be another year before the economy returned to growth. While Canada fared better than some other countries, the Great Recession’s impact was significant. Among those most affected: Canadians just entering the workforce.

Evidence suggests the health of the economy at the start of a person’s working life can accelerate, or delay, a person’s entire career.Periods of joblessness or underemployment can allow skills acquired in school to deteriorate,hamper the acquisition of important new skills, and delay opportunities for moving into specialized or management roles.It can take years to catch up.

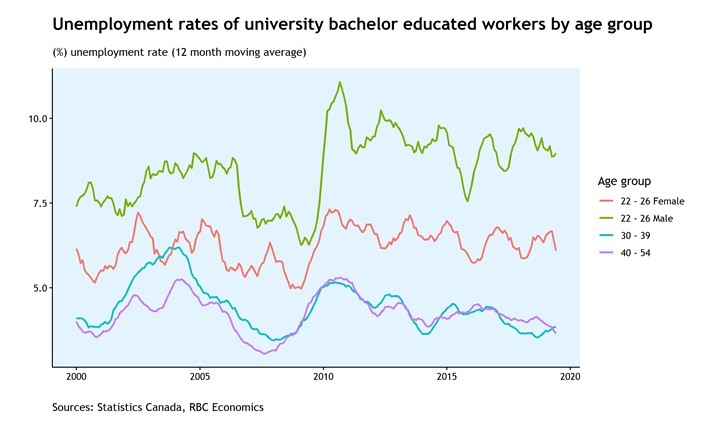

As with previous recessions, the Great Recession hit young Canadians the hardest. The unemployment rate for those 20-24 rose from about 9% in 2008 to more than 12% in 2009, adding 55,000 people to the jobless rolls. For young men, the unemployment rate hit a high of 15%. Many chose to weather the storm in school: enrollment rates at part– and full-time post-secondary programs rose from 39% in 2008 (at the time, a recent low) to 43% in 2012.

Even after they ventured into the labour market, unemployment rates for this group remained persistently high long after things had improved for older workers. And men were disproportionately affected. Young women with a bachelor’s degree fared better, likely because they were more likely to be employed in healthcare and educational services occupations that largely avoided any negative employment shock.

Recessions Influence the Jobs We End up In

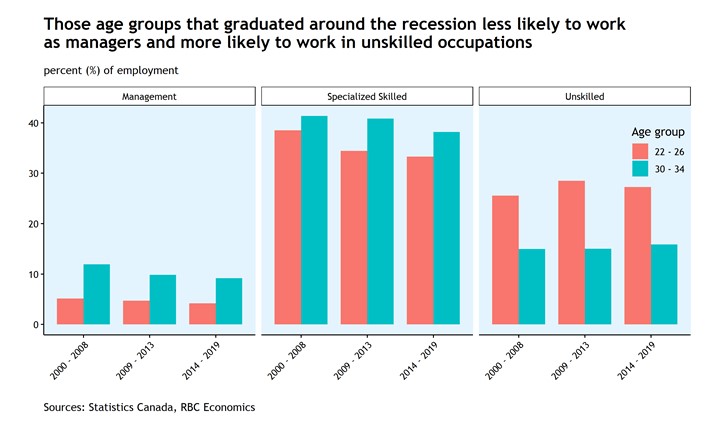

Beginning your career when the labour market is slack can affect the type of work you do. After the Great Recession,more young, university-educated Canadians found themselves doing jobs that didn’t match their education level—especially compared with those entering the workforce in the first part of the 2000s. They were more likely to be working part-time, and not by choice. They were less likely to be working in specialized skilled or managerial roles, and more likely to be working in unskilled occupations.

Precarious employment or difficulty finding work in your field is costly, in terms of lost wages. The impact may be long-lived. Wage growth is typically fastest early in one’s career, because it’s the time when one starts accumulating marketable skills. Studies indicate about one-half of the total increase in earnings over one’s career occur in the first decade. Creating a track record of competence is key to securing future promotions or changing employers. Consistent employment is also a big factor. As the Bank of Canada has highlighted, a significant portion of wage gains over a person’s life come from making job changes while employed, so periods of unemployment remove an important bargaining chip in negotiating a higher salary.

Persistent unemployment or underemployment can allow specialized skills earned in university to atrophy, increasing potential wage losses. It can also delay the acquisition and development of transferable and soft skills, an area we at RBC Economics have focused on because of the outsized importance we believe these skills will hold in the workforce of tomorrow.

Millennials’ Experience Illustrates the Impact

The costs of graduating into a recession are starting to show up in today’s 30-34-year-old cohort, who were 19-23 when the recession hit. Less than 10% are in a management position. During the 2000-2008 period, workers in that age cohort occupied 12% of management positions. Meanwhile, 37% of today’s 30-34-year-olds are in a skilled occupation; their share in the 2000-2008 period was 41%. They’re more likely to be working in an unskilled occupation compared with pre-recession cohorts.

Earnings for the graduates of the Great Recession have also lagged. Average hourly wages of those who likely entered the workforce between 2009 to 2011 have seen about 60% of growth over the first 10 years of their working lives, compared with 71% growth for those who entered the workforce between 2006 and 2008. We are only just getting a clear picture of those who entered the workforce between 2013 and 2015, but their wages appear to be stronger.The recession cohort’s slower wage growth may reflect the fact that they transitioned into management and skilled occupations at a slower rate than other cohorts. The next five years will tell us if these career delays persist.

Our findings line up with other academic studies on this issue. One recent study led by University of Toronto professor Philip Oreopoulos looked at how Canadian graduates did over the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s depending on whether they graduated during a recession or not. Total earnings penalties averaged about 5% over the first 10 years of a career, after which time wages caught up.

A Slow Career Start Could Have Significant Spillover Effects

We’ve outlined some of the costs of graduating into a downturn, in terms of lost wages in both the short and longer term. Those losses could have a host of repercussions for the individual and for the economy as a whole.Lengthening the time it takes to repay student debt or save for a down-payment on a home are two. Investing early for one’s retirement is another. Timing isn’t everything, but it can’t be ignored.

Download the PDF

Andrew Agopsowicz is a Senior Economist working in both the Economics and Thought Leadership groups. He studies the labour market – largely focusing on the future of work, demographic change, diversity, and human capital. Before joining RBC, Andrew was a Senior Economist at the Bank of Canada.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More