Canada has the world’s longest coastline. At 243,000 km, it can circle the world nine times.

This expanse plays a critical role in the Canadian economy, supporting 300,000 jobs, anchoring critical trade routes and providing over $31.7 billion annually to gross domestic product from marine transportation, seafood production and energy.

Yet its greatest potential—as a weapon in the fight against climate change—remains largely untapped.

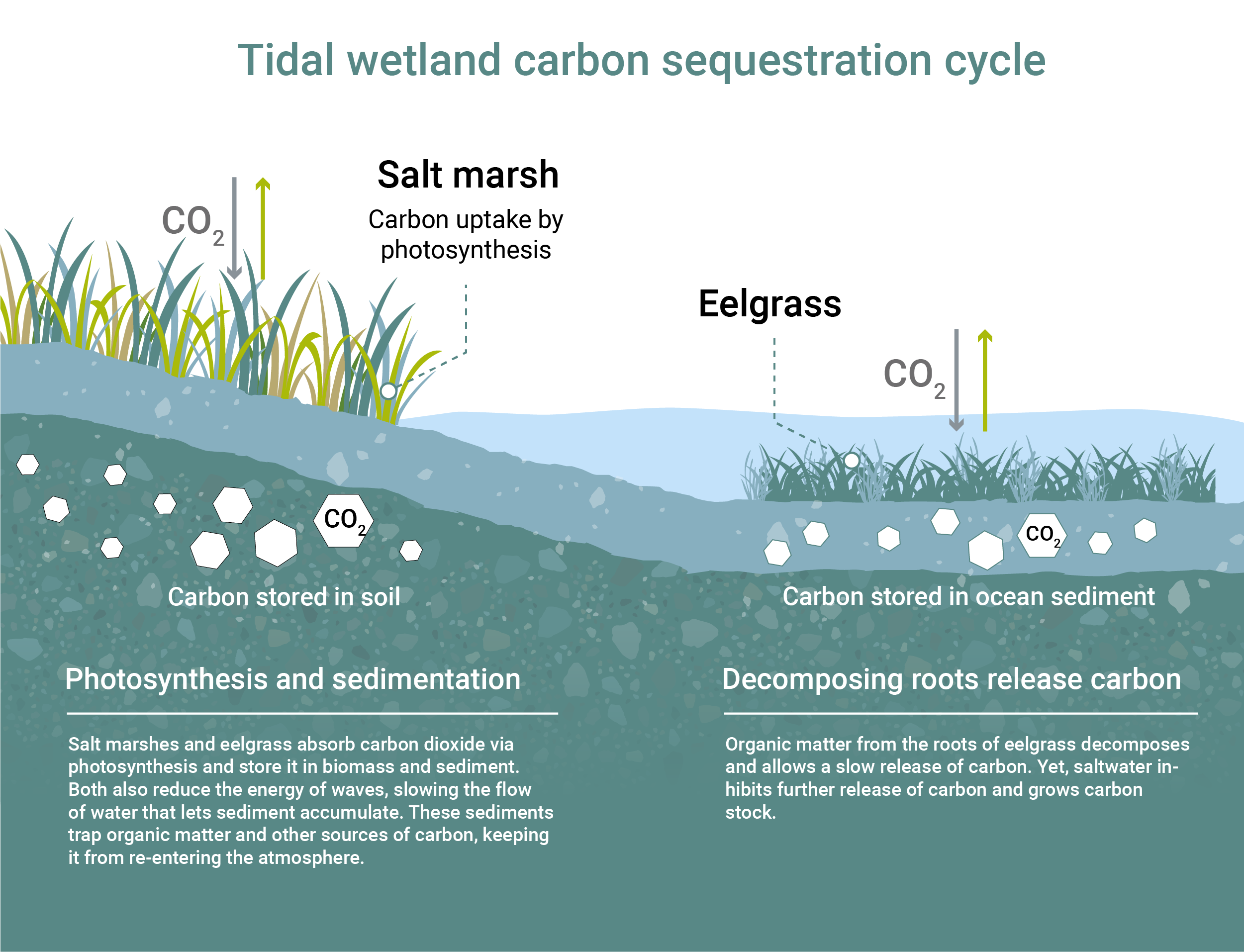

The ocean’s power to sequester carbon—pushing us closer to our climate targets—is unmatched by any other sector. It absorbs 31% of global CO2 emissions, capturing and storing blue carbon through a variety of processes involving mangroves, seagrass (known as eelgrass in Canada) and salt marshes.i

And the financial toll of ignoring it is growing as more nations take on the challenge of mapping their seabeds and developing nascent blue carbon markets. Blue carbon credits are worth two to three times more than typical carbon credits—largely because of significantly higher sequestration potential and additional ecosystem services. Early estimates suggest Canada’s blue carbon represents a US$3.5 billion market opportunity.

Eelgrass and Salt Marshes

- Eelgrass is a breed of seagrass found off Canada’s Atlantic, Pacific, Arctic coasts.

- Eelgrass promotes biodiversity and is a habitat for marine life like eels, lobsters, crabs, and cod. Unlike kelp or seaweed, eelgrass develops roots and flowers.

- Salt marshes are found across Canada’s coastline. They act as a transitional zone between terrestrial and marine environments and are a buffer against coastal erosion.

- Salt marshes provide a critical habitat for a variety of plant and animal species.

The great Canadian coastal mapping challenge

Realizing this economic potential could bring significant cross-sectoral benefits: helping fisheries become more resilient, rewarding conservation, and improving national defense through the mapping of seabeds and coastlines. But to make it happen, we’ll need to grapple with many of the same obstacles facing soil sequestration efforts, including scientific challenges that begin with how to measure and verify the carbon sequestered in coastal ecosystems.

Our most precious blue carbon assets

While other marine organisms, like macroalgae, can sequester and store carbon, eelgrass and salt marshes are the most promising blue carbon assets we have. This is both because of their sizeable current carbon stock and the immediate benefits their ecosystems provide. Through chemistry and the process of photosynthesis in marine organisms, carbon dioxide dissolves in water to create carbonic acid—a form of carbon that doesn’t easily escape the ocean. Eelgrass (a marine plant with ribbon-like leaves) can store twice as much carbon as terrestrial forests while salt marshes can sequester carbon 11 times more efficiently than grasslands and around 125 times more than forests.

Roughly 90% of eelgrass meadows in Atlantic Canada have been decimated since the 1930s. And salt marshes in many coastal regions have been converted into agricultural lands or have been flooded to make way for hydroelectric dams.

Current figures suggest the global blue carbon market is worth over US$190 billion (81 million metric tons of carbon) with countries like Australia, Indonesia, The Bahamas, and many more involved.ii Despite Canada’s potential to become the largest player in this market, our presence will remain minimal without a national blue carbon strategy.

Action is needed now. Here are three key steps for building a made-in-Canada blue carbon strategy:

Step 1:

Indigenous communities must take the lead

For any blue carbon strategy to be successful, Indigenous communities must be key stakeholders in its management. Many of the remaining eelgrass meadows and salt marshes across Canada are in or are close to Indigenous communities and are protected for food provisions and ecological integrity. For instance, the Cree protect eelgrass because Canada geese, a staple in their diet, feed on it.

Tasks like mapping and monitoring carbon stock levels—critical to voluntary offset markets—can be best organized and led by Indigenous communities. And ultimately, blue carbon programs can provide a new source of revenue for these groups.

Technology that can map ecosystems and measure carbon sequestration is not currently effective in Canada. Satellite imaging and drones can be helpful in certain circumstances, but unlike tropical regions where clarity is high, Canada’s coastline waters are too murky to be mapped with these tools. While hyperspectral imaging might overcome present challenges, satellites are only now starting to use sensors with such capabilities. The most effective approach, while lengthy, is to manually map locations. Many Indigenous communities across Canada have already started to do this. Funding for skills development in data science and information systems is needed to ensure Indigenous groups are prepared to administer carbon credit protocols as effectively and profitably as possible.

Step 2:

Start with mapping and research

A voluntary offset market for Canada’s blue carbon assets is key—and won’t happen without mapping and research. As with agriculture, we need to develop effective measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) systems that can ensure activities that sequester higher amounts of carbon are monitored accurately.

Over 300,000 hectares of eelgrass meadows and salt marshes have already been identified along Canada’s shoreline. But this is likely just a sliver of our blue carbon assets (experts say we may have only mapped only 10% of our entire coastal seabed). Mapping of Canada’s shoreline has been both understudied and underfunded—particularly in comparison to other nations. The Bahamas recently found over 9.2 million hectares of seagrass meadows off its coastline, dwarfing Canada’s official stock.iii

Mapping takes money. Though the Blue Carbon Canada initiative received $1.59 million in funding for three years of research to assess the carbon stock of eelgrass, salt marshes, and kelp, much more will be needed to truly understand Canada’s potential.

What’s holding us back? In part, a mindset that identifies extraction as more important than conservation. For a long time, mapping Canada’s coastline did not present as viable a business case as mining or fishing. The rise of a blue carbon market could change that narrative. But Canada will need to catch up to countries that are decades ahead in mapping their coastlines.

Canada has only started to earnestly advance efforts to study its shoreline in the past three years. The United States is arguably decades ahead, particularly in studying the carbon sequestration cycles of eelgrass and salt marshes. This is mainly due to the many restoration, water quality, and biodiversity projects involving seagrass and salt marshes across the U.S., especially in Chesapeake Bay.

Step 3:

Start conserving and restoring eelgrass and salt marshes now

Canada’s viable blue carbon market can be valued at US$130 million annually or US$3.5 billion cumulatively by 2050, according to figures on the assessed size, carbon stock, and rate of sequestration of its eelgrass and salt marshes. By 2030, eelgrass and salt marshes located in tidal wetlands could sequester 17.2 MT of CO2e/year. iv However, according to new research from the University of British Columbia, the total carbon stock of eelgrass in the top 100 cm of sediment holds an estimated 88 million metric tons of carbon. v

A voluntary blue carbon credit market can equip companies and organizations to buy and sell carbon offsets to meet their own objectives. Unlike compliance markets, voluntary markets are self-governed and do not legally mandate that participants reduce emissions. But voluntary markets complement compliance markets and offer private actors the opportunity to buy, generate, and sell carbon credits. Asset owners, like businesses, private investors, public agencies, or non-governmental organizations can purchase these credits. The benefits of voluntary markets are that unlike compliance markets, projects that are more experimental and innovative can be launched (in part due to less restrictive regulatory oversight). They offer participants the opportunity to reduce their emissions outside of a compliance market and expand the pool of participants.

| Type of carbon offset market | Compliance | Voluntary |

|---|---|---|

| Regulated by national, regional, or international reduction regimes |  |  |

| Open market for trading and generating credits |  |  |

| Rely on independent standard bodies |  |  |

| Legally mandated reduction of emissions |  |  |

| Optional reduction of emissions |  |  |

However, to develop a successful and effective blue carbon program, we must evolve from conserving current blue carbon assets to restoring lost marine ecosystems. Eelgrass and salt marsh ecosystems already have a substantial carbon stock and are efficient at sequestering carbon while acting as vital marine habitats. It takes years to plant eelgrass or restore salt marshes that can then grow to store and sequester carbon. And destroying them leads to the release of carbon that has been stored for millennia. Conservation activities should be focused not only on declaring protected environmental areas, but also limiting any human activity that can disrupt them.vi Such initiatives can include the development of management plans for coastal ecosystems, promoting sustainable fishing, and preventing the destruction of habitats.

Restoration of eelgrass and salt marshes will take at least a decade to complete and these projects will come online gradually. Still, it’s critical that we start now. Eelgrass meadows can take at least a decade to grow and even longer to sequester carbon efficiently. Salt marshes can grow swiftly by comparison, but oftentimes we need to reflood areas that were converted for agricultural use. Restoration projects can issue valuable and high-quality carbon credits, but they also have the net benefit of increasing fishing stock as a marine habitat.

Ultimately, conservation and restoration initiatives must also support local community values and needs, biodiversity, and rural development. Releasing the carbon currently stored in eelgrass meadows and salt marshes will also come with a hefty toll. The “social cost of carbon” is estimated at US$2.5 billion annually.

Conclusion:

Perfection is the enemy of execution

Canada cannot wait for perfection. We must start executing a blue carbon strategy immediately. To succeed, the federal government should consider adopting a two-pronged approach.

First, eelgrass and salt marsh ecosystems that currently store carbon ought to be protected. Policies should be developed with communities that depend on fisheries for their livelihoods to ensure their buy-in and participation in future blue carbon markets. A clear separation of departmental jurisdiction between Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) and Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) can ensure program rollouts aren’t trapped in bureaucratic overlaps. For instance, ECCC has dominion over salt marshes till the high tide line, while DFO manages the ocean at large. Major funding for climate change research is mainly diverted to ECCC, oftentimes leaving DFO’s expertise and research on climate change aside. For this strategy to be effective, both departments ought to be involved and have their roles clearly defined. Through an intergovernmental top-down approach, the federal government can also motivate and guide provinces to collect data on existing blue carbon assets.

Second, studies into the carbon stock of eelgrass meadows and salt marshes need further funding. Government should collaborate further with researchers to develop a national blue carbon stock account and understand that promising results will emerge within years, not months. This research will contribute to the policy development of any voluntary market that issues credits based on blue carbon. It will ensure measurements fit within the proper magnitude of carbon sequestration measurement.

Blue carbon can be Canada’s defining initiative against climate change. We just need to rise to the challenge.

Contributors:

Lead author: Mohamad Yaghi, Agriculture and Climate Policy Lead, RBC

RBC

Naomi Powell, Managing Editor, Economics and Thought Leadership

Farhad Panahov, Economist

Darren Chow, Senior Manager, Digital Media

Acknowledgements:

Kristina Boerder, Research Scientist Future Of Marine Ecosystems Lab, Dept. of Biology, Dalhousie University

Mary O’Connor, Professor, Department of Zoology, Director, Biodiversity Research Centre, The University of British Columbia

Melisa Wong, Ph.D., Research Scientist, Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Nicolas Gruber et al.,The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007.Science 363,1193-1199(2019).DOI:10.1126/science.aau5153

- Friess DA, Howard J, Huxham M, Macreadie PI, Ross F (2022) Capitalizing on the global financial interest in blue carbon. PLOS Clim 1(8): e0000061. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000061

- Gallagher, A.J., Brownscombe, J.W., Alsudairy, N.A. et al. Tiger sharks support the characterization of the world’s largest seagrass ecosystem. Nat Commun 13, 6328 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33926-1

- C. Ronnie Drever et al., Natural climate solutions for Canada.Sci. Adv.7, eabd6034(2021). DOI : 10.1126/sciadv.abd6034

- Christensen, M.S. (2023). Estimating blue carbon storage capacity of Canada’s eelgrass beds. University of British Columbia.

- Additionality will be a challenge in some circumstances where eelgrass meadows or salt marshes may be located near tributaries of forests that have issued credits.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More