U.S. unemployment rate drops again in September

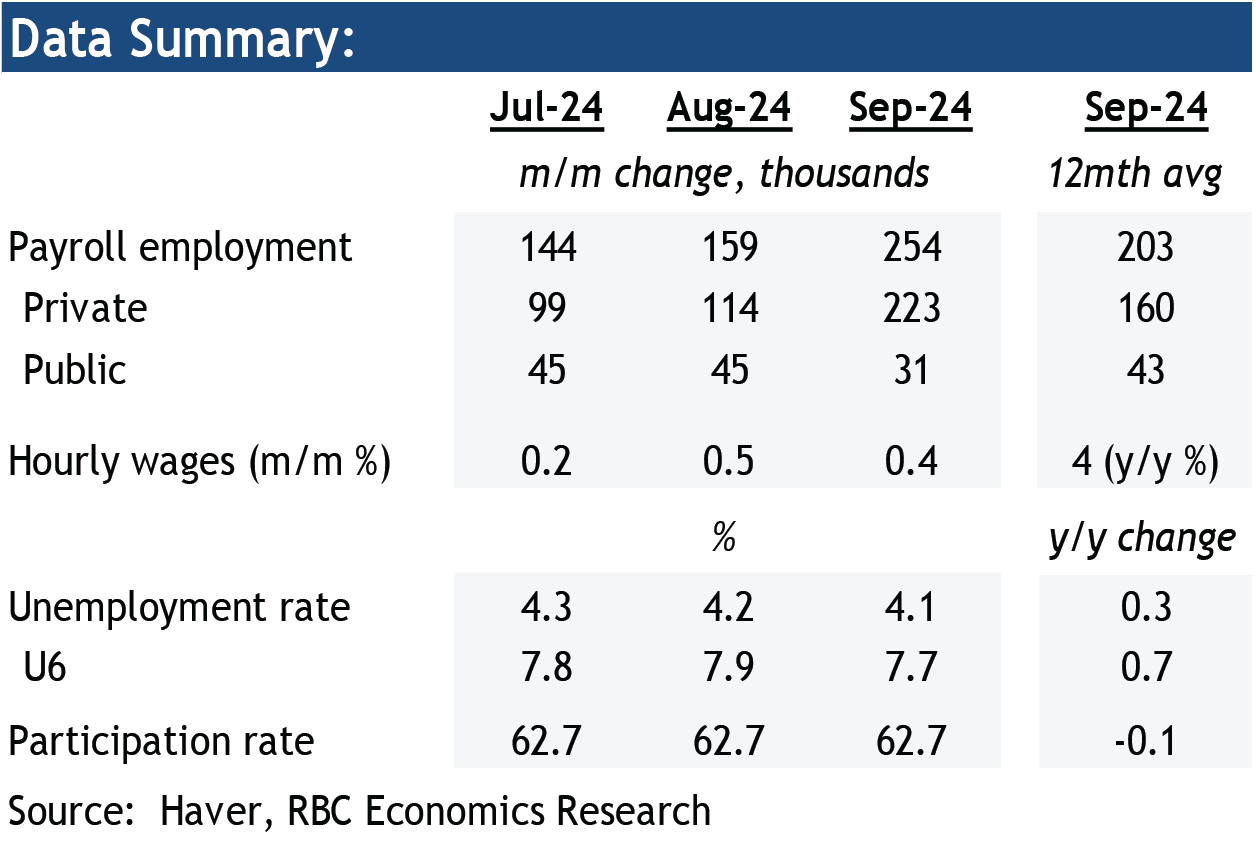

- September’s U.S. employment report beat expectations by printing a solid 254k employment gain alongside a tick lower in the unemployment rate, to 4.1% (consensus was for 140k employment gain and a 4.2% unemployment rate).

- The strong report saw dropping market odds for another 50-bps rate cut in the Fed’s next meeting in November – the payroll gain was the largest in six months. Leisure and hospitality led the increase, adding 78k jobs thanks to smaller-than-usual seasonal decline this September. Health services (+45k) and government hiring (+31k) also contributed.

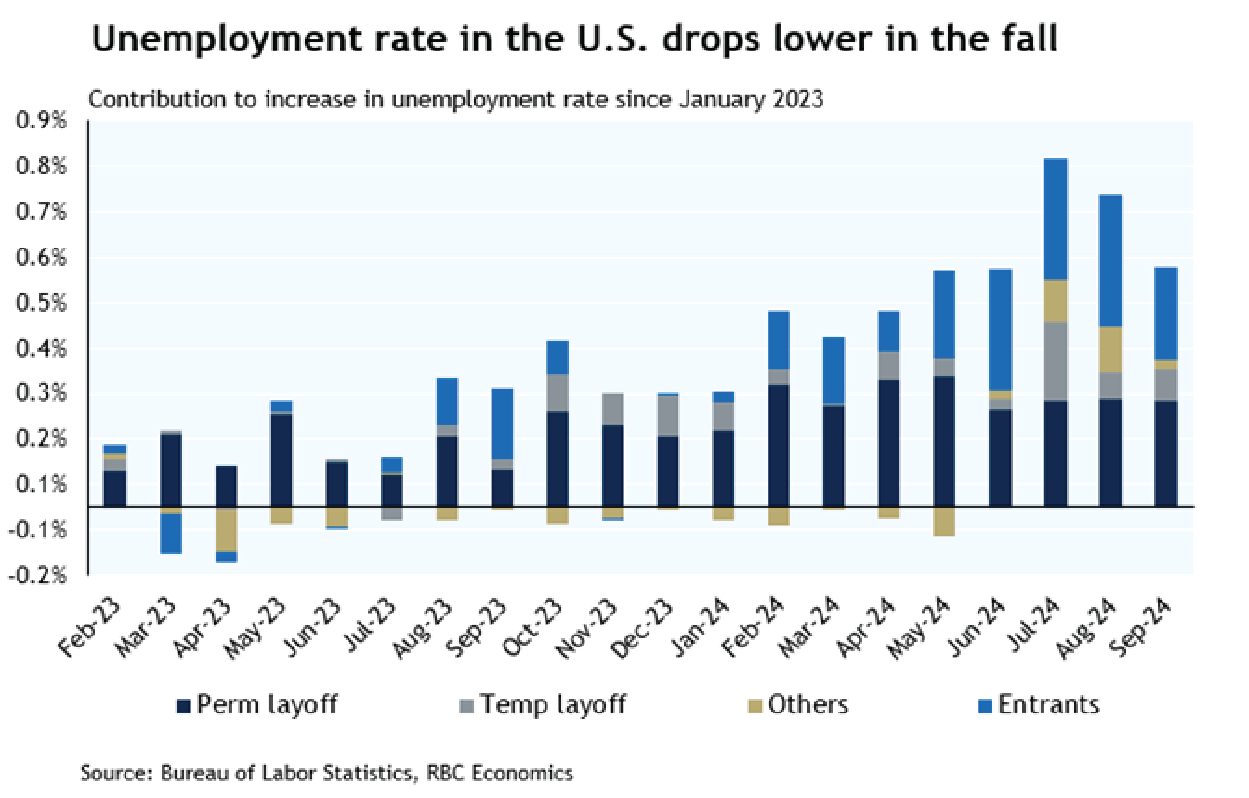

- The number of workers on both temporary and permanent layoffs were little changed in September, and 10% and 18%, respectively, higher than levels one year ago.

- Total hours worked among private industry employees fell slightly in September by 0.1%, with gains in constructions and leisure and hospitality more than offset by losses in other services sectors including retail.

- After a larger monthly increase in August, average hourly earnings rose by a robust 0.4% to push the yearly reading for wage growth higher to 4% in September. This was after cooling labour demand that has led yearly wage growth persistently lower from almost 6% in spring of 2022.

Bottom line:

- If you take September’s U.S. monthly jobs report as the best gauge of the health of the U.S. economy, the most recent report says conditions are far from crumbling, but holding onto the “American resilience” theme just fine. Taken alone, the strength of the report will take the pressure off of the Fed to reduce rates by another 50bps chunk at its November 7th meeting and ups the chances of a 25bps cut, though with still plenty of data to contend with before then.

- The story isn’t completely cut and dry, however. Other U.S. jobs market data, like job openings quit rates and various surveys still suggest momentum is trending downwards and will keep the U.S. central bank focused on downside risks, happy to be surprised to the upside as opposed to the reverse.

- For Canada, a more aggressive downturn in the U.S. has long been a risk for the economy that’s suffering from its own set of domestic challenges. We think today’s U.S. Jobs report also take some of those worries away from the Bank of Canada as they grapple with a 25bps or 50bps cut decision on October 23rd. Although they still have plenty to contend with.

See previous versions:

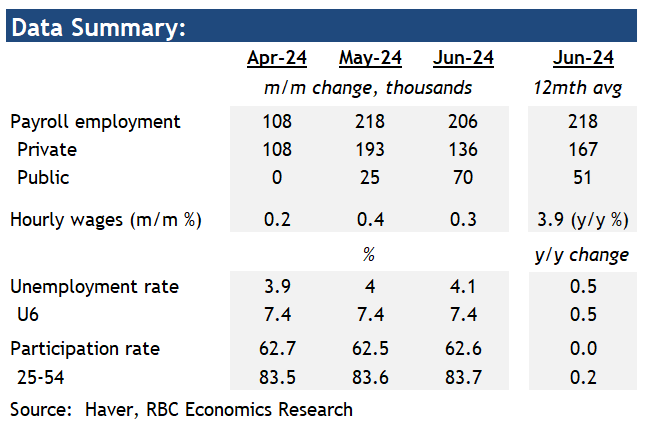

- U.S. non-farm payroll gain of 206k in June was close to consensus but after downward revisions to each of April and May that shaved 111k off of employment gains in those prior months.

- In June, it was again new hires in government (+70k) and health services (49k) that accounted for the lion’s share of job growth. All other private sector employment grew by a smaller 90k, with gains in construction (+27K) and wholesale (+14K) offset by losses in professional and business services (-17k), retail (-9k) and manufacturing (-8k).

- The separately released household survey showed the U.S. unemployment rate ticking higher to 4.1%. That’s half a percent higher than the unemployment rate a year ago while the labour force participation rate stayed unchanged from last year, at 62.6%.

- Among the unemployed, those that were jobless for 27 weeks and more saw a sharp rise in June, by 166k to 399k above levels a year ago.

- Total hours worked among private industry employees contracted by 0.2% in June after a big gain in May. On a quarterly basis, private hours worked increased by about 2% (annualized) in Q2.

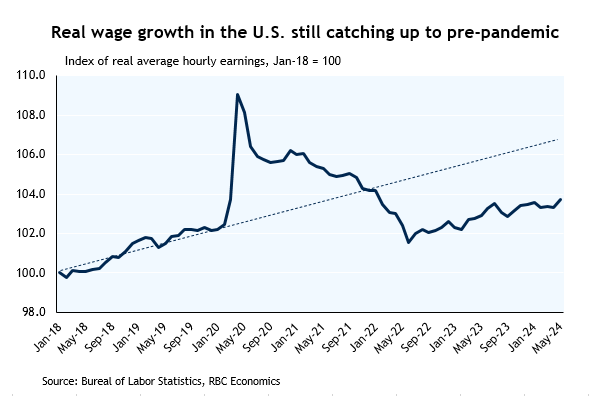

- Finally, wage growth after having risen sharply in May slowed in June. Average hourly earnings rose by 0.3% or 3.9% from last year. To-date, a lot of that increase still reflects a catching up to past high inflation – real hourly earnings as of May (the last available CPI data) grew by 0.4% each year since 2019, much slower than the 1.1% trend rate in the three years pre-pandemic.

- Bottom line: June brought another robust payroll gain in the U.S. but according to the meeting minutes, FOMC participants have begun to question if job gains in the establishment survey have been overstated with the separately calculated unemployment rate continuing to rise. Jobless claims have been broadly edging higher in recent weeks and survey data has also pointed to rising uneasiness with employment situation among consumers in the U.S. Overall, the slowdown in labour market conditions is evident but slow, just as the progress with easing inflation. That means the Fed will need more time and more data before committing to lowering interest rates. We think won’t come until December.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More