Canada's resource sector has an investment problem.

Capital spending in the mining and oil and gas industries stands at about half 2014’s total. While there are several reasons for this — falling commodity prices, high costs and market access issues, to name a few —regulatory uncertainty and lengthy delays in approving key projects have played a significant part. The federal government is seeking to address the regulatory challenge through Bill C-69, which would overhaul the review process for major infrastructure projects. The intent is to improve transparency and add clarity to the approval process, both for project proponents and Canadians. The overhaul’s goals are ambitious. They include speeding up project approvals while encouraging sustainability, and giving the resource sector a stronger social license to profitably develop natural resources. Bill C-69 would have the most impact on the energy and mining industries, which collectively support 15% of Canada’s economy and directly or indirectly employ almost one in 10 Canadians. Will the proposed framework allow for the meaningful consultations that public courts and industry leaders seek, while also delivering the certainty investors need? At stake: $582 billion in planned energy and mining projects over the next decade.

Fewer Projects

Canada’s resource-extraction sector is in the doldrums. Capital spending fell from a peak of $90 billion in 2014 to $48 billion in 2016 and has since flat-lined. The country’s share of global oil and gas investment fell to 6% in 2018 from almost 9% four years earlier.1 Investment intentions point to another year of stagnation in 2019. The story outside of Canada has been different. US mining, oil and gas investment also saw a significant decline between 2014 and 2016 but rebounded strongly in the following two years. Globally, oil and gas capex has increased by more than US$40 billion since 2016.

Foreign investors are losing interest in Canada’s natural resources sector. We’ve seen growing net outflows of foreign direct investment in energy and mining over the last three years. Since 2016, Canadian companies have invested $23 billion abroad in the energy and mining sectors, while FDI inflows totalled just $4 billion. Major international energy companies have fled Western Canada, selling more than $30 billion in oil-sands assets since 2016. The number of oil and gas companies operating in the region fell by 17.5% between 2014 and 2018.2 And last year, the oil and gas industry raised just $5 billion in debt and equity financing, a 78% decline from the previous year.3 It’s not just investment that’s leaving. Canada lost 57,000 jobs in mining and energy between 2014 and 2016 and has recovered just a quarter of those positions since. While Canadian companies in the mining, oil and gas industries were cutting jobs at home, they added 29,000 positions in their foreign operations between 2014 and 2016.

Several Hurdles

The pullback reflects a number of factors. Commodity prices have been front and centre. The Bank of Canada’s energy price index fell by more than 50% between 2014 and 2016, while metals and minerals prices were down more than 10% over that period and about 1/3 below their 2011 highs. Recent improvement in prices—energy prices are up 1/3 since 2016 and metals and minerals prices are 10% higher—hasn’t been accompanied by more investment, as it has elsewhere. This underscores that Canada-specific issues are at play. Political and regulatory uncertainty and high tax and regulatory costs (particularly vis-à-vis the US following its corporate tax cuts and deregulation push) have all been cited as deterrents to investment. Well-publicized legal challenges have mired some key infrastructure projects in lengthy delays, likely acting as another headwind.

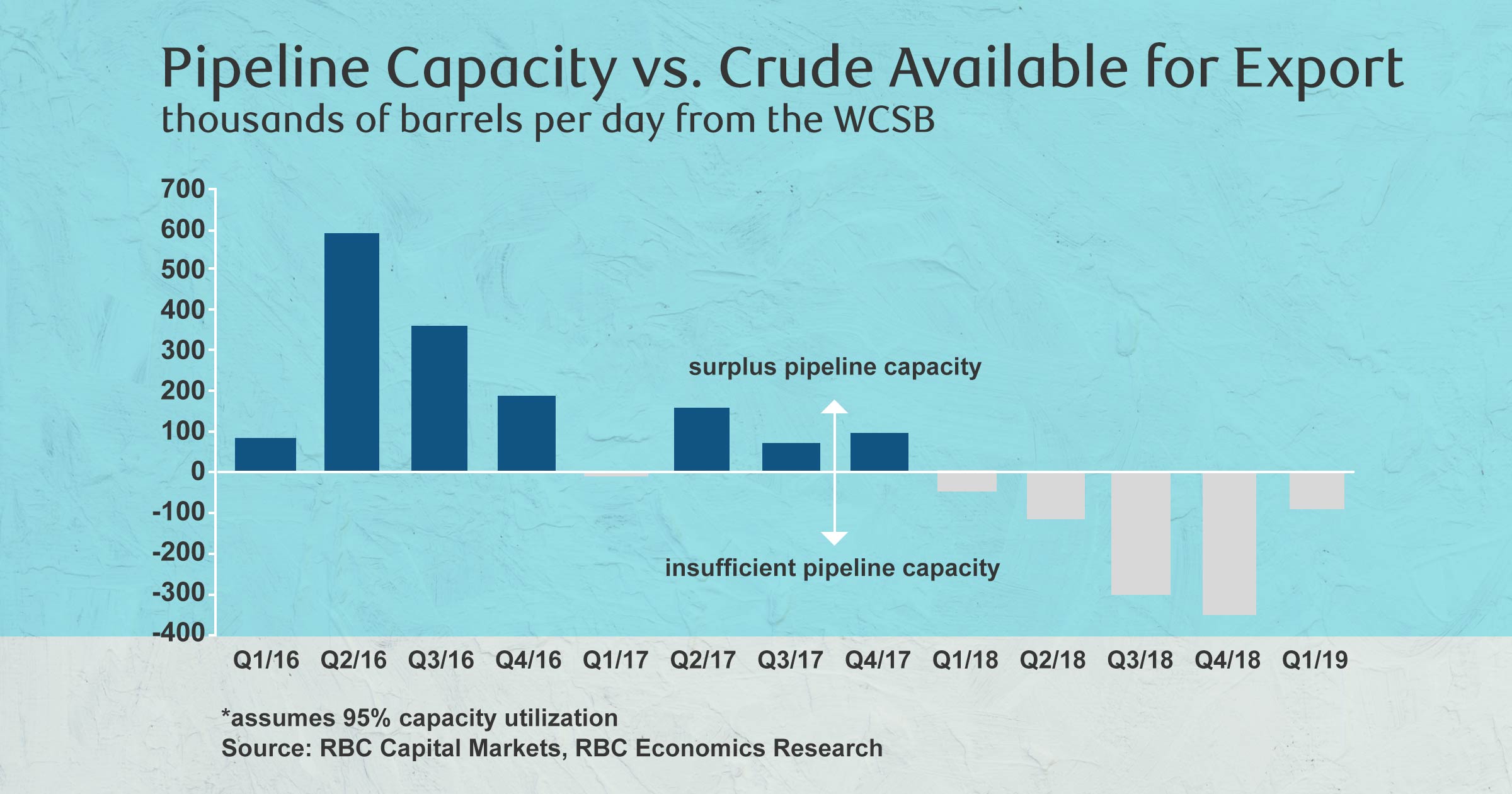

Canada’s inability to add enough pipeline capacity to keep up with growing oil-sands production continues to be a pain point. Consider projects that would have added key takeaway capacity — the Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion, Northern Gateway, Energy East. The latter two were cancelled, while Trans Mountain still faces hurdles. An EY report commissioned by the Canadian Energy Pipeline Association found the average time to approve oil and gas pipeline applications increased from 357 days in 2009 to 681 days in 2016.4 Meanwhile, the US application process has only lengthened marginally since 2009, with approval times for gas pipelines actually falling in recent years (the study did not include US oil pipelines). The study noted that the US has seen 14 new applications for large-scale pipelines since 2016, whereas just one such project (a natural gas pipeline) has been submitted to the National Energy Board in Canada.

It’s not just a pipeline problem. A CD Howe study found mining projects in Canada took three years to approve, compared with two years in Australia. And the maximum time for a mining project’s approval was 15 years in Canada—more than twice that in Australia.5 The prospect of such a lengthy approval process may have deterred some applications altogether. On the oil and gas side, the Fraser Institute’s Global Petroleum Survey shows Alberta’s “Policy Perception Index” has declined in recent years, with the province’s global rank slipping from 14th in 2014 to 43rd in 2018.6 Nearly half of respondents said environmental regulations were a strong deterrent to investment, while the cost of compliance, uncertainty regarding enforcement, and regulatory duplication/inconsistency were also barriers to investing in Alberta. British Columbia and Saskatchewan have also seen their policy perception scores decline.

A Proposed Solution

The federal government believes Bill C-69 would address the regulatory challenge. A key aspect of the new project review process is earlier and more extensive consultation with Indigenous peoples and other stakeholders, with the goal of avoiding the court challenges that have plagued some major projects. Bill C-69 also attempts to give proponents more certainty over timelines. It sets a 180-day timeline for the planning phase, 300 days for impact assessment (or 600 days for more complex projects where a panel review is required), and 30 to 90 days for decision making. Impact assessment timelines have been shortened relative to the current process. However, those timelines don’t include “clock stop” time for proponents’ responses to information requests. According to CD Howe, clock stoppage accounted for more than half the duration of environmental assessments for mining projects, and 25% for non-mining energy projects.7 Those timelines are also subject to extension by the Minister for Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

What does Bill C-69 change? Bill C-69 changes the federal review and approval process for major infrastructure projects—those that have the greatest potential for adverse environmental effects on areas that fall wi

thin federal jurisdiction. The goal is to reduce regulatory uncertainty, provide more meaningful Indigenous and public consultation, deliver timelier decisions, and avoid the court challenges that have delayed some of Canada’s major infrastructure projects in recent years. Federal impact assessment is currently conducted by the National Energy Board (NEB), Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC), or Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency (CEAA) depending on the type of project. Under Bill C-69, a new Impact Assessment Agency (IAA) would handle all federal impact assessments, while the Canadian Energy Regulator (replacing the NEB), CNSC, and Offshore Boards would be responsible for lifecycle regulation of those projects. This isn’t just a shuffling of agencies—the process itself would change quite significantly. Currently, environmental assessment focuses on minimizing adverse environmental effects. The proposed framework focuses on sustainability, broadening the assessment process to include positive and negative environmental, health, social and economic impacts. A new early planning phase is meant to engage Indigenous peoples, stakeholders and the public at the outset. Legislated timelines for the review and decision-making process would be shortened, though timelines can be extended by the ECCC Minister. Who would be impacted? The new review process covers many of the same types of projects that were subject to impact assessment by the NEB, CNSC and CEAA. The proposed Project List touches many areas: renewable energy, onshore and offshore oil and gas, transportation (including interprovincial and international pipelines), mining, and nuclear energy would all fall under the IAA’s umbrella (subject in some cases to thresholds based on project size). The most notable change in scope is that in situ oil production—smaller projects that use steam rather than open-pit mining to extract oil-sands bitumen—would now be subject to federal assessment unless those projects are governed by a GHG emissions cap. That seems intended to deter the new Alberta government from removing the previous government’s 100 Mt cap on oil-sands emissions. Other changes include a higher review threshold for mining and pipeline projects, a lower threshold for tidal power generation, and the addition of offshore wind power generation to the Project List.

Industry Concerns

Some industry advocates, most significantly in the oil and gas sector, worried that Bill C-69 in its original form wouldn’t reduce regulatory uncertainty or speed up the approval process. Criticism centred on a few key issues. Some warned that broadening the scope of factors considered in the environmental-assessment process would increase uncertainty for project proponents. How a project contributes to sustainability—through its environmental, health, social, and economic impacts — wasn’t well defined, they argued, and it was unclear how much weight would be applied to various considerations. There was also concern that the economic benefits of a project wouldn’t be given sufficient weight in the decision-making process. And while one of its goals is to ensure more meaningful public consultation, Bill C-69 wasn’t explicit about who should have an opportunity to participate, critics said. There were also concerns Bill C-69 would increase the role of politics in the review process — most significantly by lowering the threshold for when a public interest determination must be made regarding a project’s adverse effects. Some of the bill’s critics recommended that the Impact Assessment Agency should be independent from ECCC, and that the ECCC Minister shouldn’t have sole authority for deciding whether a project is in the public interest. There were also calls to limit—or increase transparency around — the ECCC Minister’s discretionary power to extend review timelines or designate a project for assessment when it falls outside the prescribed Project List. After public consultation and hearings on Bill C-69, the Senate’s energy, environment and natural resources committee proposed close to 200 amendments to the bill. Some of the changes specifically addressed industry concerns. As compared to the original bill, the amended bill reduces the ECCC Minister’s discretionary powers, increases the role of lifecycle regulators (like the CER and offshore petroleum boards) in the review process, sets more explicit guidelines for public consultation, and clarifies factors that would be considered in impact assessment, including putting more emphasis on economic benefits. The Senate adopted the committee’s report and, after a third reading, will send the amended legislation back to the House of Commons.

The Stakes are High

There is plenty at stake in the government’s attempt to improve the impact assessment and approval process. The industries most affected represent a big chunk of Canada’s economy. The energy sector—from oil and gas extraction, refining and distribution to electricity generation— accounted for 7.5% of the country’s economic output in 2018. The minerals and mining industries and associated downstream operations represent another 3.3% of GDP. Combined, those two sectors are equivalent in size to Canada’s manufacturing industry. And when indirect effects are included, energy and mining represent more than 15% of Canadian GDP. While those industries haven’t been significant sources of job growth in recent years, they remain major employers, directly and indirectly supporting more than 1.5 million Canadian jobs. 8,9

While these industries have struggled to attract investment, there is still plenty of capital spending in the pipeline over the next decade. But recent trends are concerning. Natural Resources Canada’s inventory of major projects shows $510 billion in planned energy investment and an additional $72 billion in major mining projects.10 The value of projects added to that list has declined in each of the last three years. In fact, a combined $167 billion in major energy and mining projects was added between 2016 and 2018, only slightly more than the $159 billion added in 2015 alone. And projects are being cancelled faster than they’re being completed. Nearly $200 billion in natural resources projects were cancelled or suspended in the last three years, while $134 billion were completed. Last year’s $77 billion in cancellations included a $12 billion oil sands-related project, two LNG projects representing $27 billion in investment, and five pipeline projects worth $27 billion. The version of Bill C-69 that’s heading back to the House of Commons differs in significant ways from the original— notably by addressing some of the resource industry’s concerns around an ill-defined consultation process and the weight placed on a project’s economic benefits. Early indications are that some of the proposed bill’s vocal opponents, both in business and the political arena, are now likely to be more receptive to the legislation. Those same amendments, of course, aren’t likely to please those who favour a more heavy hand in resource regulation. In the end, however, Bill C-69’s fate may rest less on philosophical differences than on legislative realities. The federal government is juggling a number of other legislative priorities before the House rises on June 21—including passing the 2019 budget and ratifying CUSMA—giving lawmakers relatively little time to consider the latest iteration of C-69 before the next election.

Read the Full Report

[1] RBC Economics calculations based on IEA World Energy Investment

[2] XI Technologies, “Word to the Wise: How much did our industry consolidate between 2014 and 2018?,” April 6, 2019

[3] Daily Oil Bulletin, “Total Oil & Natural Gas Financings Down 78 Per Cent In 2018,” February 27, 2019

[4] EY prepared for Canadian Energy Pipeline Association, Regulatory competitiveness in Canada’s pipeline industry

[5] CD Howe, A Crisis of Our Own Making: Prospects for Natural Resource Projects in Canada

[6] Fraser Institute, Global Petroleum Survey 2018

[7] CD Howe, A Crisis of Our Own Making: Prospects for Natural Resource Projects in Canada

[8] Natural Resources Canada, Energy and the economy

[9] Natural Resources Canada, 10 Key Facts on Canada’s Minerals Sector

[10] Natural Resources Canada, Natural Resources: Major Projects Planned or Under Construction—2018 to 2028

RBC Economics provides RBC and its clients with timely economic forecasts and analysis.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More