A choppy year ahead for the global economy

Advanced economies’ fight against inflation and geopolitics will continue to be the overarching themes of 2023. Interest rate increases and Russia’s restriction of European energy supplies over the past year will further weigh on households, business investment and economic growth. As China’s struggle with its zero-COVID policy continues, the world’s biggest economies–the U.S., China, and the European Union, representing over half of global GDP–are headed for recession or slow growth in 2023.

More economic downside risks are hovering.

Rising interest rates and slowing growth threaten distress for highly-indebted economic sectors. The stronger U.S. dollar makes the foreign-currency debts of emerging markets more onerous and exports inflation globally. If central banks are not able to thread the needle on rate hikes, policy errors can spark a deep recession.

Other risks are geopolitical. With its military momentum flagging, Russia may squeeze weakened Western economies by restricting energy supplies, lifting prices and testing their support for Ukraine. Weak national balance sheets could heighten economic rivalry even between friendly countries.

Just as the global economy continues to navigate COVID-19 and its aftereffects, new headwinds appear to be emerging–structurally tighter labour markets, higher interest rates, increased costs of emitting greenhouse gases, lower gains from trade, and inadequate preparations for energy security and national defence.

The year 2022 presaged the potential implications: rising global competition in an increasingly unsettled energy sector, securing a foothold in new industries, fighting for talent, and determining who pays for the high cost of transitioning to the new economy. Fierce competition could decouple economies and erode global prosperity.

As much as 2023 is bound to be a challenging year, there are bright spots. Most likely inflation returns close to target with only moderate recessions in most advanced economies. Structural shifts present opportunities to invest now in climate, capital, and people. Co-operation within Europe and among Western nations may continue to regress Russia’s position in Ukraine. Weak economic growth could also prompt countries to walk back from the precipice, recognizing the need to cool geopolitical tensions.

It adds up to a volatile 2023 as the global economy transitions to the post-pandemic era.

Canada faces variations of these global challenges. High household indebtedness, elevated housing markets, and prospects of further policy divergence with the US Federal Reserve will make it difficult for the Bank of Canada to judge the perfect rate path to bring down inflation while minimizing growth impacts.

The Canadian outlook could be shaken by global developments. Further weakness in the US, deep recession in Europe, or financial market spillovers from economic or geopolitical events would erode growth prospects. Changing commodity prices have a relatively neutral overall economic impact, but are consequential for individual consumers, provinces, and industry.

Top of mind is how Canada finds its way in the new economy, attracting talent in tight and shifting labour markets and establishing new growth industries in climate and advanced technologies. In some ways it will mean navigating the perennial challenge of fraught geopolitics between economic giants without being trampled or caught flat-footed.

Here are some themes to consider as we head into 2023.

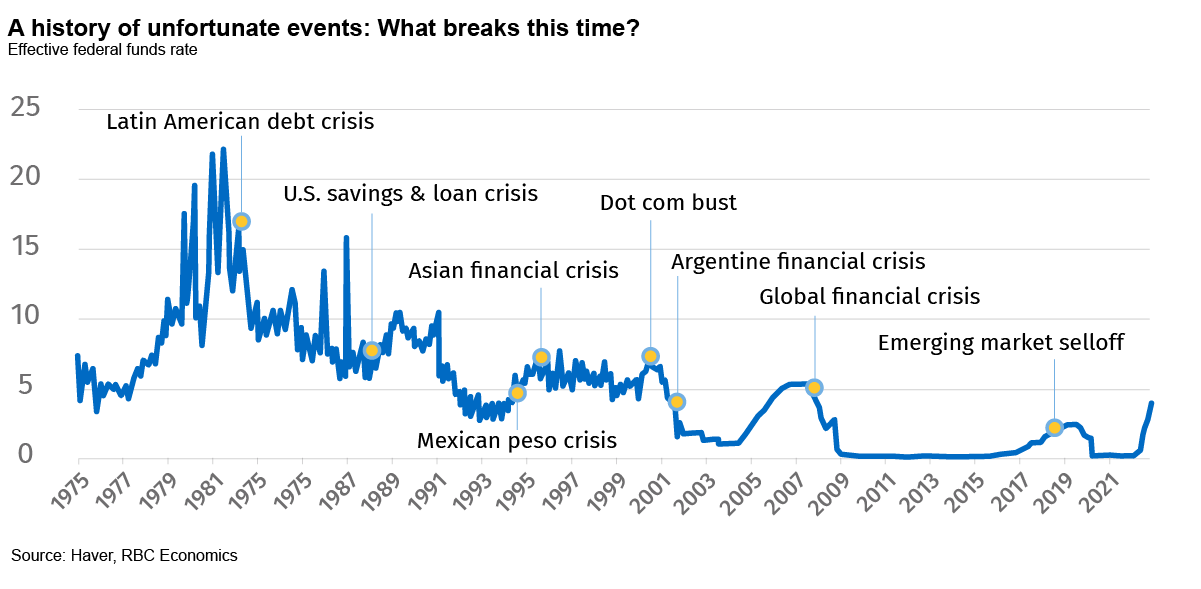

Historically, monetary tightening in the global reserve currency tends to have reverberations worldwide, exposing financial vulnerabilities and leading to local crises. This time around, the US Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate hikes, combined with investor flight to safety, have pushed up the US dollar against most currencies.

Advanced economies have seen the greatest relative depreciation, with the dollar up close to 10% since the start of the year on a trade-weighted basis. Currency depreciation is a moderate 5% for developing economies, reflecting better economic performance and, in some cases, strong commodity prices.

For advanced economies, the associated easing of financial conditions (as imports become more expensive and substitution puts pressure on domestic goods and services) complicates the central banks’ fight against inflation. Higher rates may be necessary, but come with risks of their own, like non-linear impacts on a highly-indebted household sector and consumption.

Emerging economies with the greatest currency weakness, such as Turkey, Argentina, Colombia and Ukraine, also have the most significant foreign-denominated debts as a share of GDP, although they are not a major share of the global economy. So far, emerging market vulnerabilities look contained, but if pressures build, global volatility or risk-off biases could be a negative for growth into next year.

Energy prices are in for a volatile year and the associated winners and losers will dictate the path of the global economy. RBC Capital Markets research has a base case forecast for Brent crude averaging about US$95 per barrel in 2023. But the forecast range is wide. The possibility of further restrictions of Russian energy exports is a major swing factor.

Net importers would be particularly challenged if further US dollar strength continues to limit a typical cushion against rising commodity prices. Rising food prices, debt-servicing requirements and higher energy prices would be major hits to household purchasing power, sending consumption and growth sharply lower. It could also complicate central banks’ efforts to re-anchor inflation expectations.

Europe would be the epicentre of these challenges. While the continent has made contingencies, it is headed into winter with natural gas prices almost 3x higher than in 2021. The European Central Bank will need to tighten further into 2023. European governments have committed €674 billion ($964 billion) in support to households and businesses, representing 2.9% of GDP in France, 3.5% in the UK, and 7.4% in Germany, adding to their large COVID-19 debts.1 A deep recession is already a possibility.

Other countries would be winners. Sectors of the Canadian economy benefit from higher oil prices, but as a marginal net exporter with limited new investment, modest price appreciation has an overall neutral impact on the Canadian economy. Not so for OPEC heavyweights like Saudi Arabia. The need to finance domestic priorities, including a stated target to diversify the economy away from fossil fuels, may hold Saudi policymakers back from offsetting supply constraints despite global pressure.

Markets are grappling with the possibility that long-term real and nominal interest rates are structurally higher post-pandemic. Current 10-year rates in both the US and Canada are above rates that prevailed for most of the last decade, seeming to reverse the march downward over the past 30 years.

In the near term, inflation expectations will play the starring role. Breakeven inflation rates suggest markets believe both the Fed and Bank of Canada will bring inflation back within target over the medium term. Our forecast has term borrowing costs edging lower through 2023. But the inflation surprise of 2021-22 builds in more uncertainty to the outlook, which should add a small inflation risk premium going forward.

Markets may also price in some probability that structural factors further drive interest rates modestly higher in the years ahead. While historical drivers of falling real interest rates like ageing societies, global inequality and constrained productivity growth remain, tight labour markets, deglobalization, and climate change could nudge real rates and inflation in the opposite direction.

Central banks are acting aggressively to enforce their credibility in the current tightening cycle and rein in inflation expectations. But any structural changes afoot suggest a moving target that may find tension with current goals. For example, if tight labour markets result in structurally higher inflationary pressures, central banks’ determination to bring inflation back to 2% would involve deeper recessions. They may see cause to turn back.

Central bankers have a clear path forward headed into 2023: to continue wrestling inflation back to target. But as the tightening cycle plays out through the year, central banks may have to manage difficult communications and tough choices.

China’s predominance in the global economy means its zero-COVID policy has a long reach. The shutdowns of major cities—including an estimated 74 cities in full or partial shutdown this past fall with a combined population over 300 million—will continue to affect global trade. China accounts for 13% of global exports and 12% of global imports.

The stringent policy has serious downside risks. Lockdowns have exposed frailties in China’s debt-ridden property market that has led to social dissent, and risks turmoil in the banking sector. To date, Chinese authorities have dealt with these vulnerabilities with typical steely resolve. Although there are some signs that the authorities are relenting, there are no easy ways out of the policy–the country’s vaccine protection remains relatively low, especially among the elderly.

Chinese authorities are battling on other fronts, too. Demographics, productivity growth, and other factors suggest China’s potential growth rate will be lower than in the past decade. China’s already fraught relationship with the West has also soured the past year over the Russia-Ukraine conflict. China has not condemned Moscow’s actions and, along with India, has been purchasing displaced Russian barrels at a discount. This schism between East and West is preventing an end to the Russian conflict and has longer-term consequences for the productivity and stability of the global economy.

US-China divisions are entrenched politically and in public sentiment. A dangerous escalation is possible. But with greater weakness in both economies driving domestic angst, an uneasy freeze in tensions may also be in the cards.

The real dimension of global trade competition has been for advanced technologies and high-value Net Zero industry, which will intensify through 2023. The Biden administration has added an accelerant—the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)—and other legislation that’s ready to dispense hundreds of billions of federal incentives for US research, climate investment, and domestic production of semiconductors and clean technologies.

The significant effort will drive competition from other countries, particularly around securing production of batteries, hydrogen, clean fuels, and others value drivers in the new energy system. The Canadian government has already declared its intention to level the playing field with US measures.

Competition will exacerbate the global headhunting drive of ageing economies. While looming recessions will add slack to labour markets, lack of workers and skills is a long-term challenge that has countries looking to immigration to fill the gap. But it’s clear that the key battlefield is for the highly skilled, with a number of countries including Canada eyeing STEM, healthcare and green economy workers. It’s not just advanced economies. China will soon feel a demographic squeeze and like India and Malaysia, is increasingly keen not to lose its own top talent to foreign economies.

This competition will be productive, pushing forward major climate infrastructure, industrial development and business investment. But it also risks going too far. Nationalistic tendencies to focus on domestic supply chains risk undermining international trade, adding costs and delaying global climate progress. With the Europeans already challenging US-centric IRA provisions, there is a danger that disputes between allies will distract from geopolitical collaboration and bolstering energy security.

Monetary policy making always involves a leap of faith. Economic activity reacts relatively quickly to policy changes long before their intended impact on inflation. It means the Bank of Canada will have to deftly stick-handle the task of keeping interest rates high enough to ensure core inflation targets are within sight, but throttling back before too many disinflationary pressures build.

That is a more difficult task these days. Canada has not seen such high inflation in 30 years nor the large drift upwards of inflation expectations. Households are much more indebted. For the first time in its history, the Bank is tightening policy at the same time as it’s managing down its balance sheet through quantitative tightening. Government spending is strong. Various factors are contributing noise or signals, from high energy prices to misbehaving supply chains to tight labour markets.

We think the Bank is at or near the top of its tightening cycle. The year 2023 could see wriggles as the Bank recalibrates with incrementally tighter policy or a pullback in rates closer to neutral. Strong household and corporate balance sheets and further currency depreciation against the US dollar may prop up spending and inflation. On the other hand, household consumption may show greater sensitivity to interest rate increases leading to more negative consumption in the near-term.

The most difficult decision will be when to pivot to an outright loosening cycle when rates are brought steadily back towards neutral. The Bank will want to avoid false starts. As negative growth data starts to roll in by early 2023, the Bank will be laser focused on hard inflation data and likely to stay put. But as the year brings further output losses, unemployment, and easing core inflation, the Bank will need to start considering taking the leap late in the year.

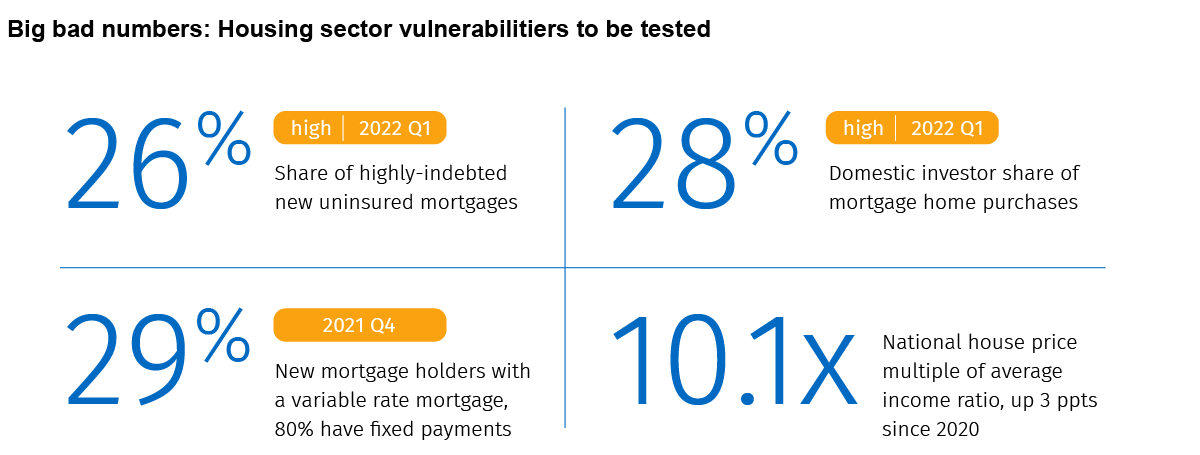

Rising interest rates, slowing home sales, and lower growth will test the housing sector. The country’s pandemic-era housing frenzy has amplified economic vulnerabilities. The share of highly-indebted new mortgage holders, variable rate mortgages, and domestic investors has jumped. House price multiples relative to average incomes have shot higher.

Housing activity and house prices have been in retreat since the spring. Further impacts are to come. Debt service ratios will climb higher through next year as mortgage renewals phase in higher interest rates. Higher unemployment will make debt servicing harder for a segment of households.

Highly-indebted households are more likely to curtail their consumption significantly and some may default—we expect an increase in household delinquency rates, which had fallen since 2020 to half the pre-pandemic rate. Along with high inflation, flagging confidence, and wealth effects from a decline in housing and equity wealth, spending and housing activity will fall further. But this is likely to be contained by the still strong overall balance sheet of the household sector and structural undersupply of housing in major cities.

More cracks could appear, especially if interest rates go unexpectedly higher. Sudden reversal of house price expectations, resets on variable rate mortgages leading to more borrower defaults, flagging confidence, or changing behaviour of speculative investors could lead to financial institutions and regulators adjusting to contain the damage. But, it’s a rare, more significant negative income shock that could lead to an ugly outcome: sizeable borrower defaults and forced house sales that put significant downward pressure on house prices and economic growth.

Business is facing conflicting signals on investment. Tight labour markets, government incentives, and new opportunities versus higher interest rates, higher corporate tax measures, and some ongoing difficulties in doing business.

These mixed signals are more exaggerated in the climate space.

The eager climate talk of the past year may fade with hard realities. The macro environment will erode project economics that were already challenged. Clean technologies tend to be beset by technology, demand, and regulatory risks. The $10-20 billion in climate investment to date has been far short of the required $35 billion per year by 2030 and at least $80 billion per year by 2050.

Still there are signs that climate could outperform. Venture capital flows into cleantech are holding up despite market-wide declines. Companies and regulators have demonstrated more rigour around company disclosures and emissions commitments. Geopolitics is driving interest in clean energy.

The federal government is also intent on tilting the scales in climate’s favour, and keeping in step with US actions. It recently announced a slew of technologies eligible for new cleantech investment tax credits in addition to other tax, concessional finance, and regulatory initiatives that will come to bear throughout 2023. Indigenous communities are increasingly participating as partners in new green infrastructure, furnishing environmental credibility and predictability.

Climate may indeed outperform, but it will likely be highly technology specific, leading to further relative underinvestment in riskier abatement technologies needed in the future. Even investment outperformance may not bring nationwide climate spending to target. And at only a portion of the current $221 billion in annual business non-residential investment, fervent climate spending would be insufficient to rectify Canada’s poor record on business investment.

With the Canadian-born working age population in decline for more than a decade, immigration has been the release valve for labour market shortages. Next year should see governments and business doubling down on another policy measure: skills development.

Canada’s labour shortages may be particularly acute as a result of the pandemic, but labour market tightness will outlive the next recession. Lack of working age people and shifting skills demand with the rise of automation, green investment and other factors will lead to chronic mismatches between jobs and workers.

The federal government has lifted immigration targets progressively since 2019 meaning an additional 2.7 million new permanent residents between now and 2035. Canada will need to attract these permanent residents in an increasingly competitive global landscape for talent. But bringing immigrants into the country is only one part of the process. Access to affordable housing and mobility, and integration into labour markets is another challenge.

With limitations to absorbing more immigrants beyond current targets, at least in the near term, 2023 should see enhanced focus on skills to better match qualified immigrant and domestic workers to labour market needs across the jobs and skills spectrum. Canada’s workers have some of the best access to on-the-job training, but availability is much lower for older, lower-skilled and small business workers. Government incentives to encourage mid-career upskilling trail international leaders. Canada also has a range of untapped talent pools, from women, Indigenous people, immigrants, and visible minorities that could boost the size of the economy.

Cynthia helps shape the narratives and research agenda around the RBC Economics and Thought Leadership team’s forward-looking economic and policy analysis. She joined the team in 2020.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More