Greener, Greyer, Smarter, Slower

The 2010s was a decade of recovery and restructuring. Post-crisis, the global economy struggled to generate sustained growth, while the emergence of new technologies—cloud computing, smart phones, artificial intelligence—began to disrupt every sector. The 2020s could see equally profound change, as those economic and technological trends collide with the growing forces of climate change and demographic disruption.

By 2030, Canada’s economy could look significantly different. A country whose economic identity has long been bound to natural resource extraction will accelerate its transformation into a services economy. Aging will present challenges to governments facing rising healthcare costs and a big tab for elderly benefits. For cities and for builders, we may need a rethink of housing policies—and indeed how we develop cities and towns—to ensure the growing inter-generational tensions over housing affordability are resolved.

That won’t be easy in a world that may not see robust global growth any time soon. The slowing down of major economies—notably the U.S., Europe and China—will continue to test monetary authorities and lead governments to apply fiscal levers.

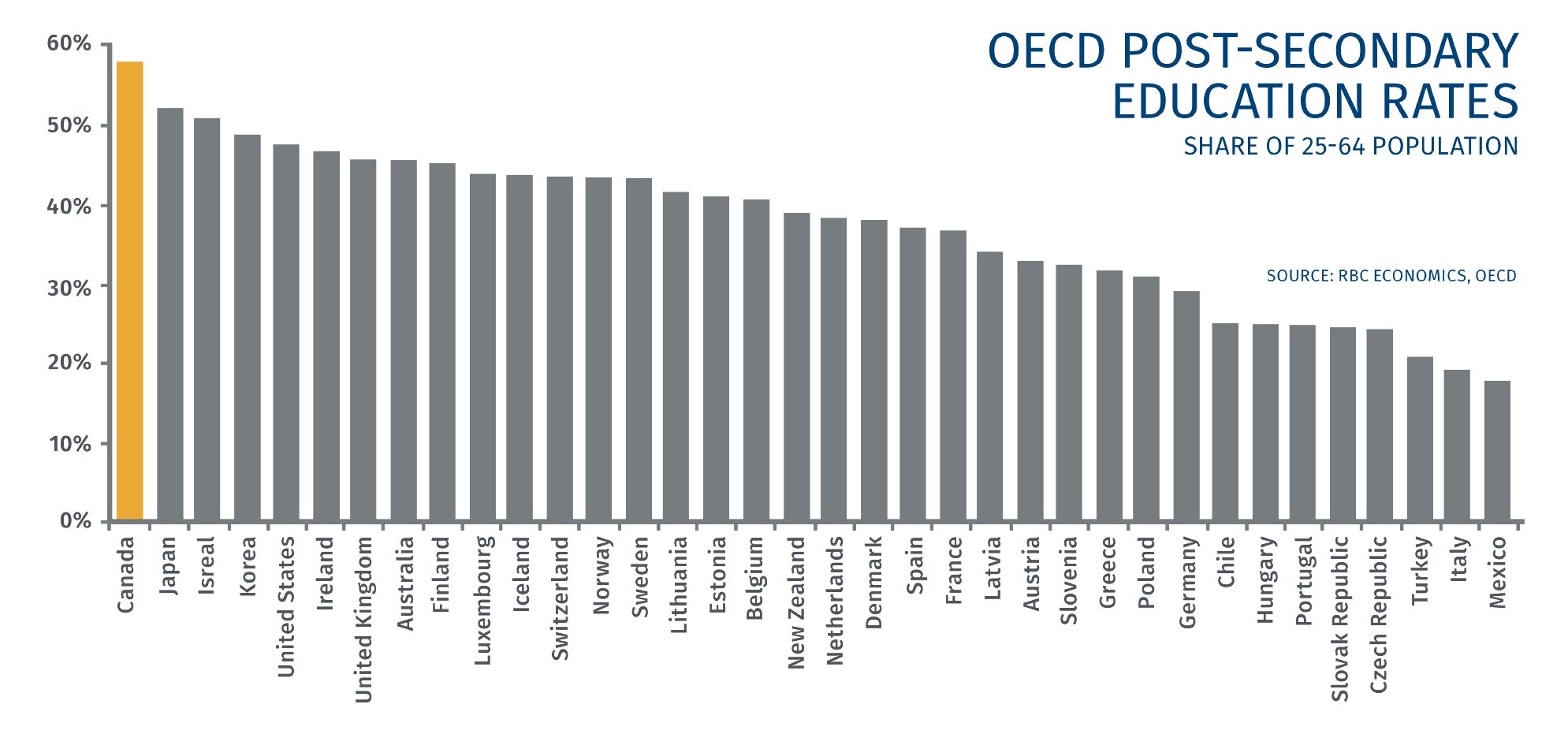

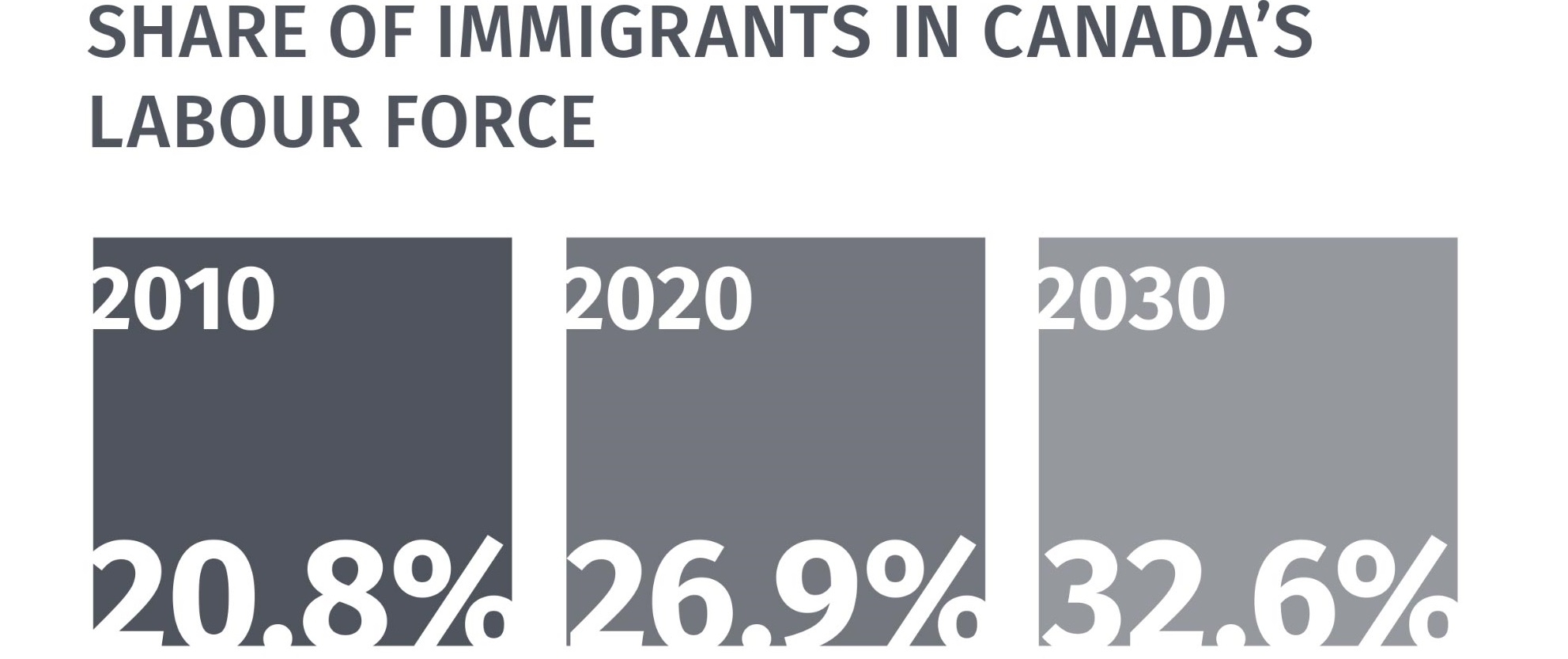

The challenges appear daunting, but Canada has a number of strengths to apply, led by an educated, immigrant-rich and diverse population. Keeping our doors open to the world’s best and brightest, diversifying our trading partners, and reducing internal barriers to trade will be essential steps to maintaining and potentially boosting our standard of living in the 2020s. So will policies—enhancing education and skills training—to help our human capital innovate and thrive. And we’ll need to keep working on closing wage gaps—for women and for immigrants—if we are to fully realize our collective potential.

Our latest report, Navigating the 2020s, explores some of the challenges ahead, as well as opportunities for Canada to thrive in a decade of change, when ideas and ambition will matter more than ever.

Download the Report

1. Greener

The Challenge

As the world warms, planning for a more sustainable future has shifted from a medium-term goal to a pressing need. For Canada, there’s particular urgency: a 2019 federal report noted that the country warmed 1.7°C between 1948 and 2016—twice the global rate.

Canada’s investment in pollution abatement and control increased tenfold in the past decade and will demand even more resources in the 2020s. The federal government’s 12-year Investing in Canada plan has allocated $27 billion to green infrastructure investment, and $7 billion in projects have already been approved. The private sector is also doing its part—Petro-Canada just completed the final charging station in its coast-to-coast electric vehicle charging network.

Climate change could influence Canadian farmers’ crop choices, put strains on existing infrastructure including ports and coastal roads, and determine the location of future residential developments. It’s no wonder central banks and investors have turned their attention to assessing the systemic risks climate change could pose.

US$2.4 trillion: Amount committed to carbon-neutral investment portfolios by 2050 by an alliance of the world’s biggest insurers and pension funds

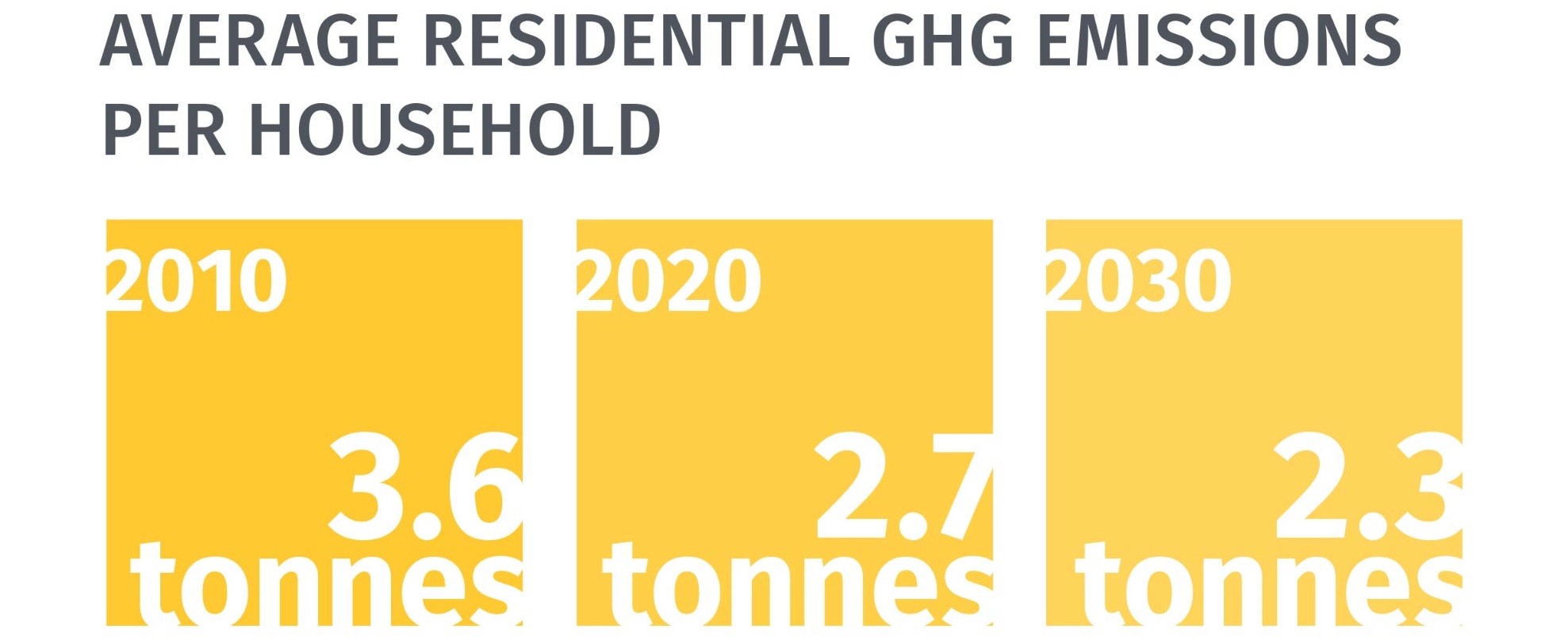

Domestic energy use is expected to decline

The Canadian Energy Regulator’s base case is for energy use per capita to decline almost 9% by 2030, and energy use per unit of economic output by more than 16%.

Canadians will be slow to get off fossil fuels, but a shift from coal to natural gas in electricity generation is expected to reduce the emissions intensity of fossil-fuel consumption. And demand for oil and refined petroleum products is expected to decline due to increased efficiencies in modes of transportation.

Lower costs for clean technologies will also help reduce the emissions intensity of electricity production. Installed capacity of wind and solar is expected to increase by nearly 50% in the next decade and will account for 9% of electricity generation in 2030, the CER says.

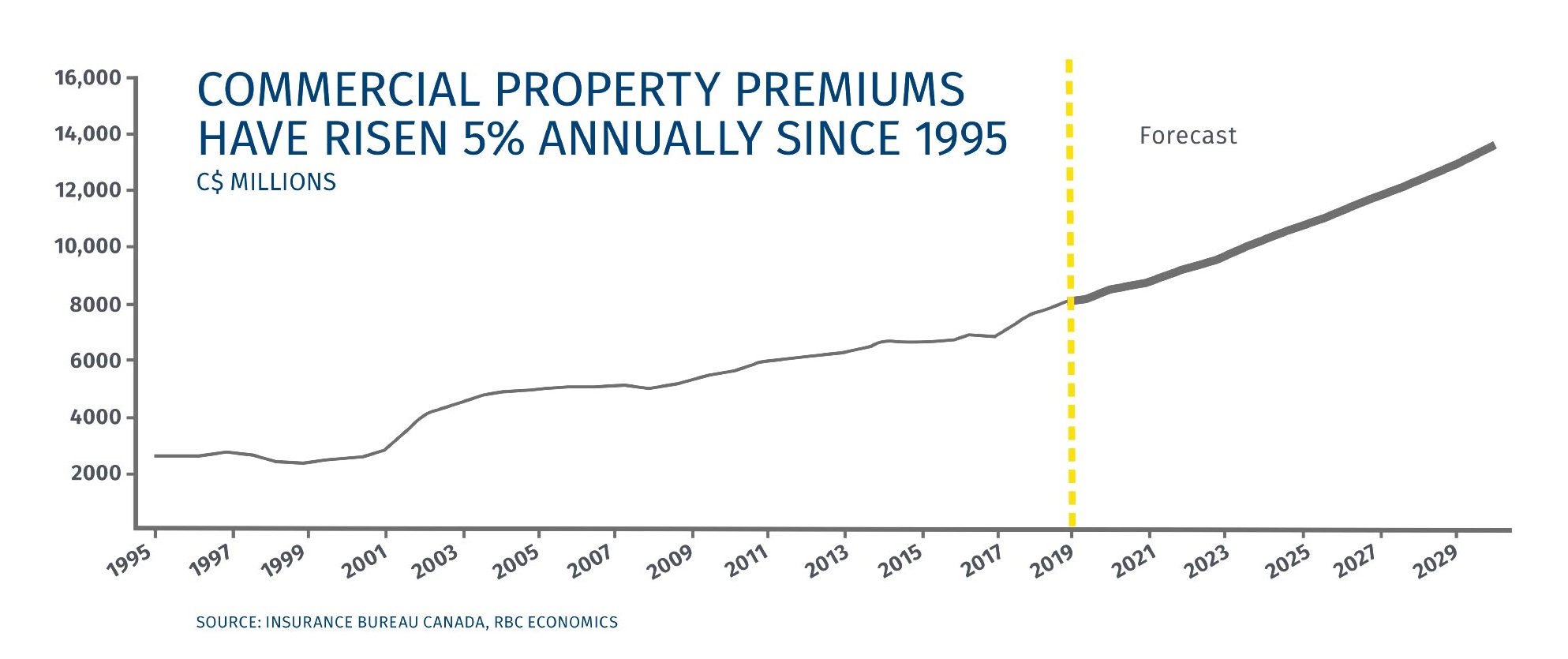

Climate change costs will weigh heavily on insurers and the insured

A warmer planet means more intense and frequent extreme weather events, and Canada hasn’t been immune. For insurers, this has meant a surge in annual claims. From the first decade of the century to the second, the average number of catastrophic events per year almost doubled, while the average annual reported insured losses quadrupled (from $0.5 billion/year from 2000-2009 to $2.02 billion/ year from 2010 to 2018) (Data from the Insurance Bureau of Canada).

Canadian households and businesses have paid the cost. Last year, half of Canadian businesses said they were struggling with high insurance costs, up from 43% the year before. Household spending on home insurance premiums has grown at almost twice the clip of overall spending over the past decade, with Canadian households paying an average of $700 for home insurance in 2017, up 35% from 2010. The risk of further increases is high.

The Opportunity

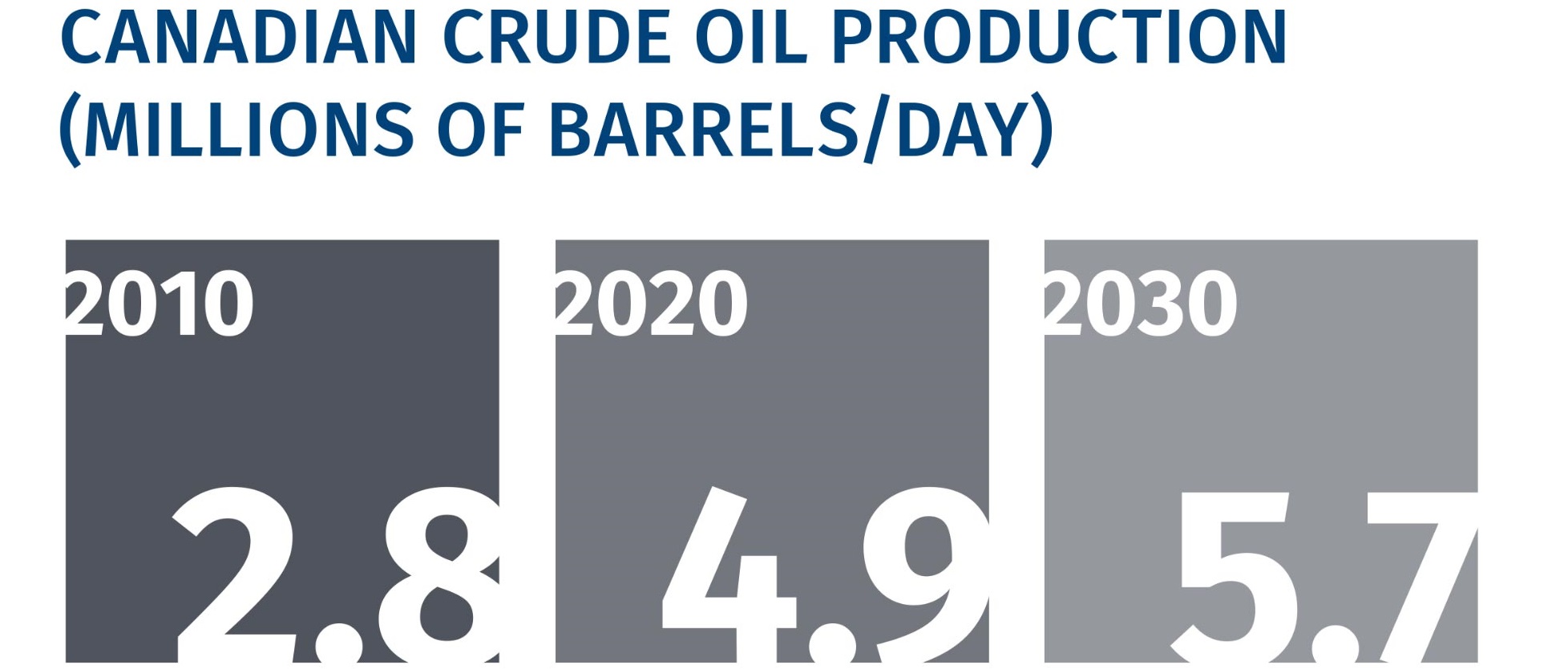

Exporting energy technology

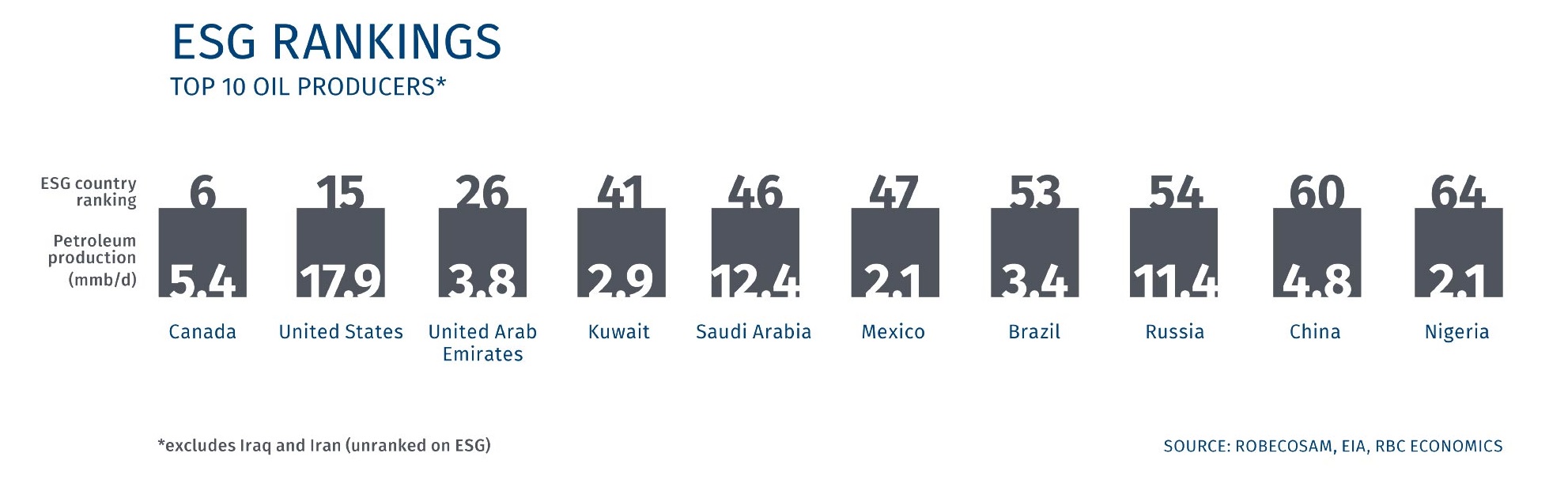

Canada will remain a major producer and supplier of energy to the rest of the world. That role will increase as new oil pipelines are built and LNG export capacity comes on stream. We expect Canadian oil sands producers, already large investors in clean technology, to continue to invest in measures that will further reduce emissions per barrel. Doing so will help Canada keep domestic emissions under control (the oil and gas sector accounts for more than one-quarter of Canada’s GHG emissions) and ensure the oil we export is as cleanly produced as our competitors.

Canada’s natural gas exports can also play a role in reducing emissions intensity abroad. LNG shipments to emerging economies in Asia, where energy demand is growing much faster than in Canada, can help replace coal in electricity production, just as natural gas is doing here in Canada.

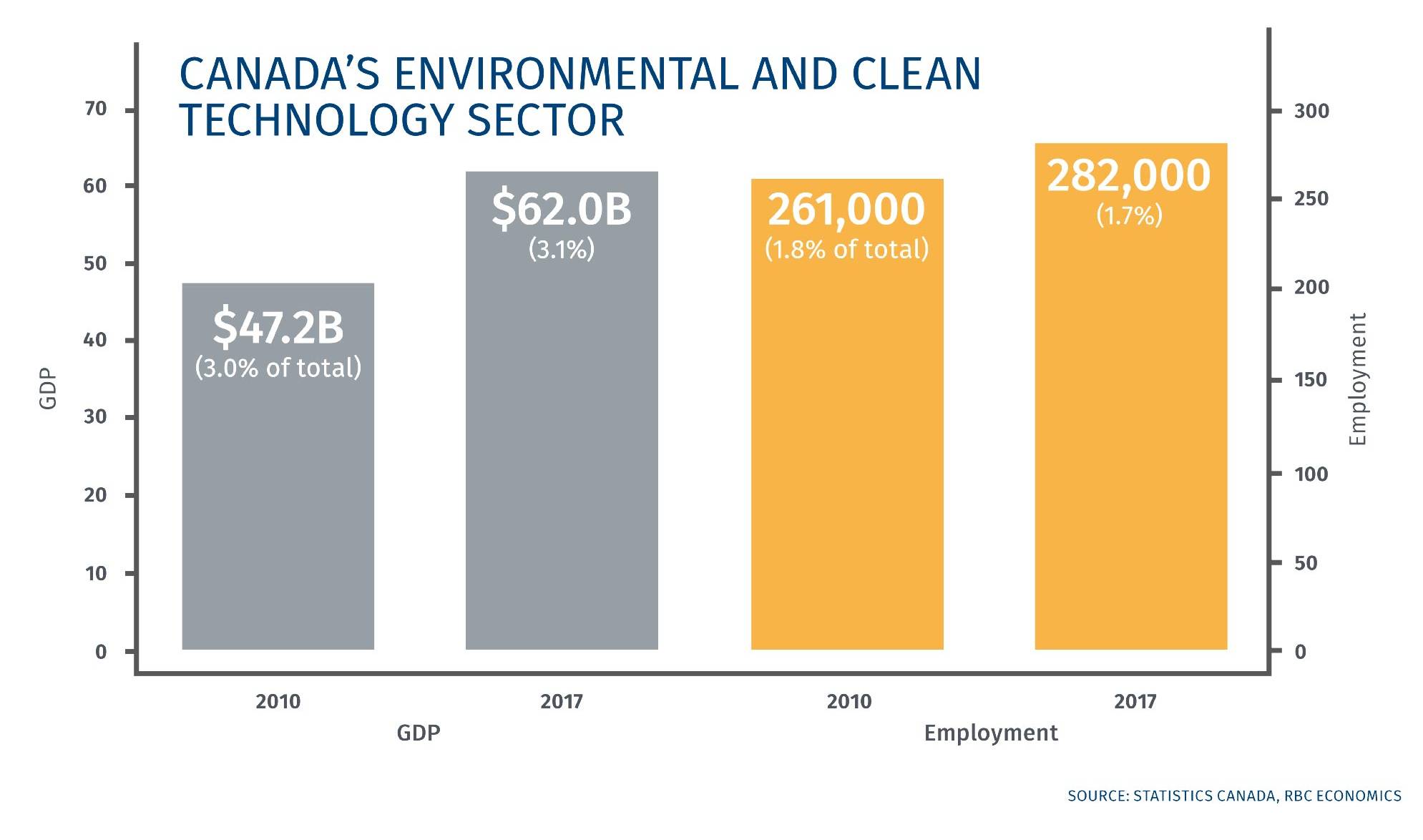

As climate concerns mount, Canada’s challenge will be to better sell ourselves as a responsible, cleaner energy producer. We already compare favourably to other oil-producing countries in Environmental, Social and Governance rankings. Canada’s oil and gas industry invests $1.4 billion a year in clean technologies, according to the Clean Resource Innovation Network, and 12 Canadian companies were among the top 100 companies in the 2019 Global Cleantech 100, an annual ranking of the companies leading in sustainable technology innovation. Ottawa has set out an ambitious target of turning Canada’s leadership in clean technologies into one of Canada’s top-five exporting industries by 2025. Its goal: a cleantech sector that would generate $20 billion in exports midway through the decade, compared with $7.8 billion in 2016.

Embracing green financing

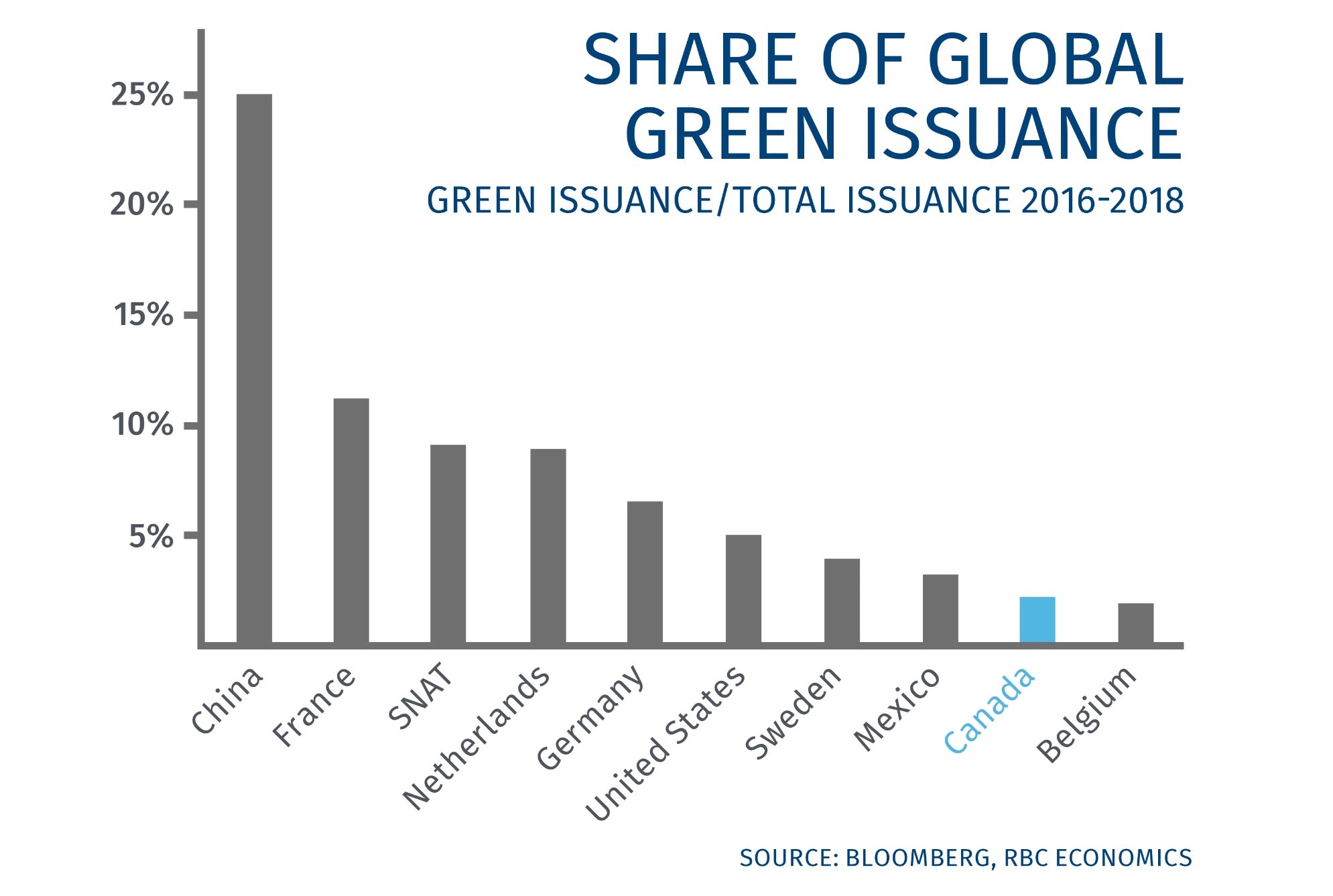

Investments required to make a shift to a greener future in Canada will be expensive. The good news: global financial markets have signaled growing appetite to finance the transition through green bonds, whose proceeds are used in projects that will mitigate or reduce climate change. Canada’s first green bond, for US$300 million, was issued in early 2014. There are now around US$15 billion in Canadian-issued green bonds outstanding. While green bond issuance remains a small fraction of total global bond issuance, it rose to US$150 billion in 2018 from just US$1 billion a decade ago. Certified green bond issuers have achieved favourable terms due to high demand and scarcity of supply.

While Canada remains a smaller player than China or France, it has seen its green bond market grow steadily, with public sector issuers leading the way. There’s plenty of opportunity to take the lead on next-generation clean projects, given Canada’s abundance of resources, well-developed financial sector and highly educated population.

2. Greyer

The Challenge

The loudest sound of the 2020s may be the ticking of the demographic time bomb. Canadians are living longer and having fewer babies. Add the advancing age of the baby boom cohort, and Canada is set to join a growing club of super-aged societies. By the end of the decade, close to one in four Canadians will be seniors, up from 17% now.

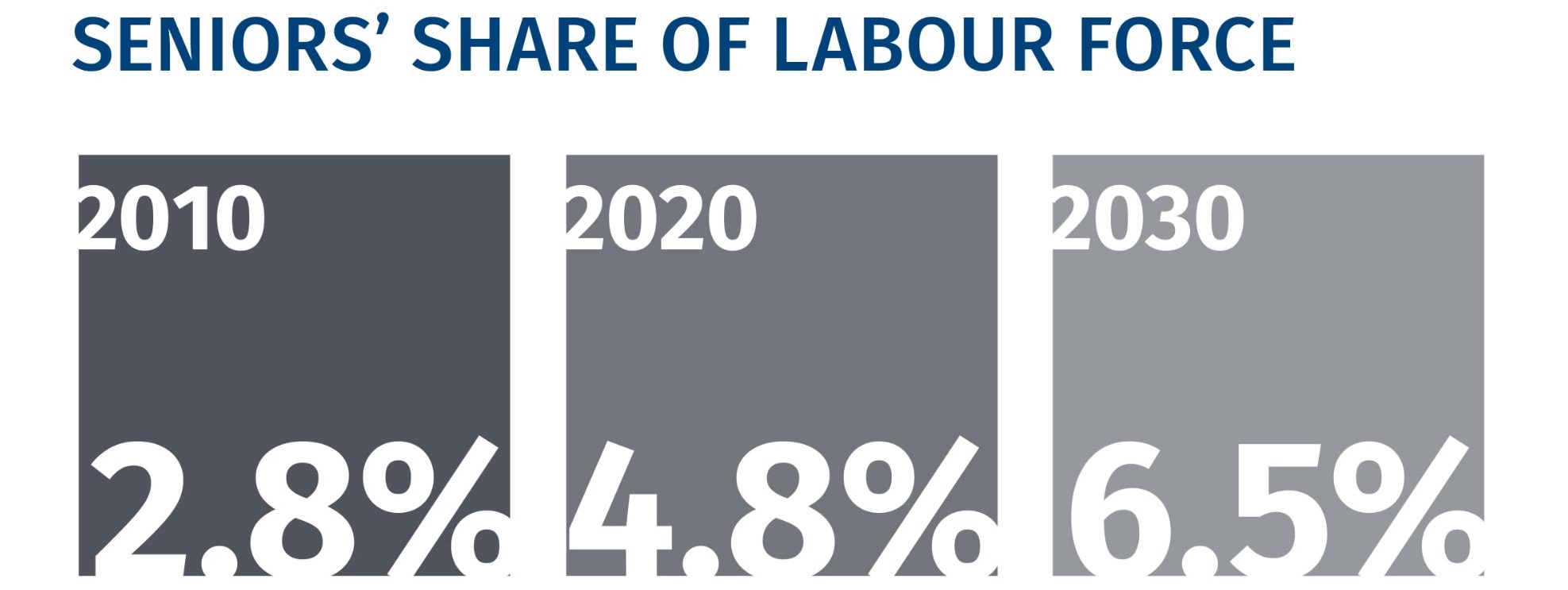

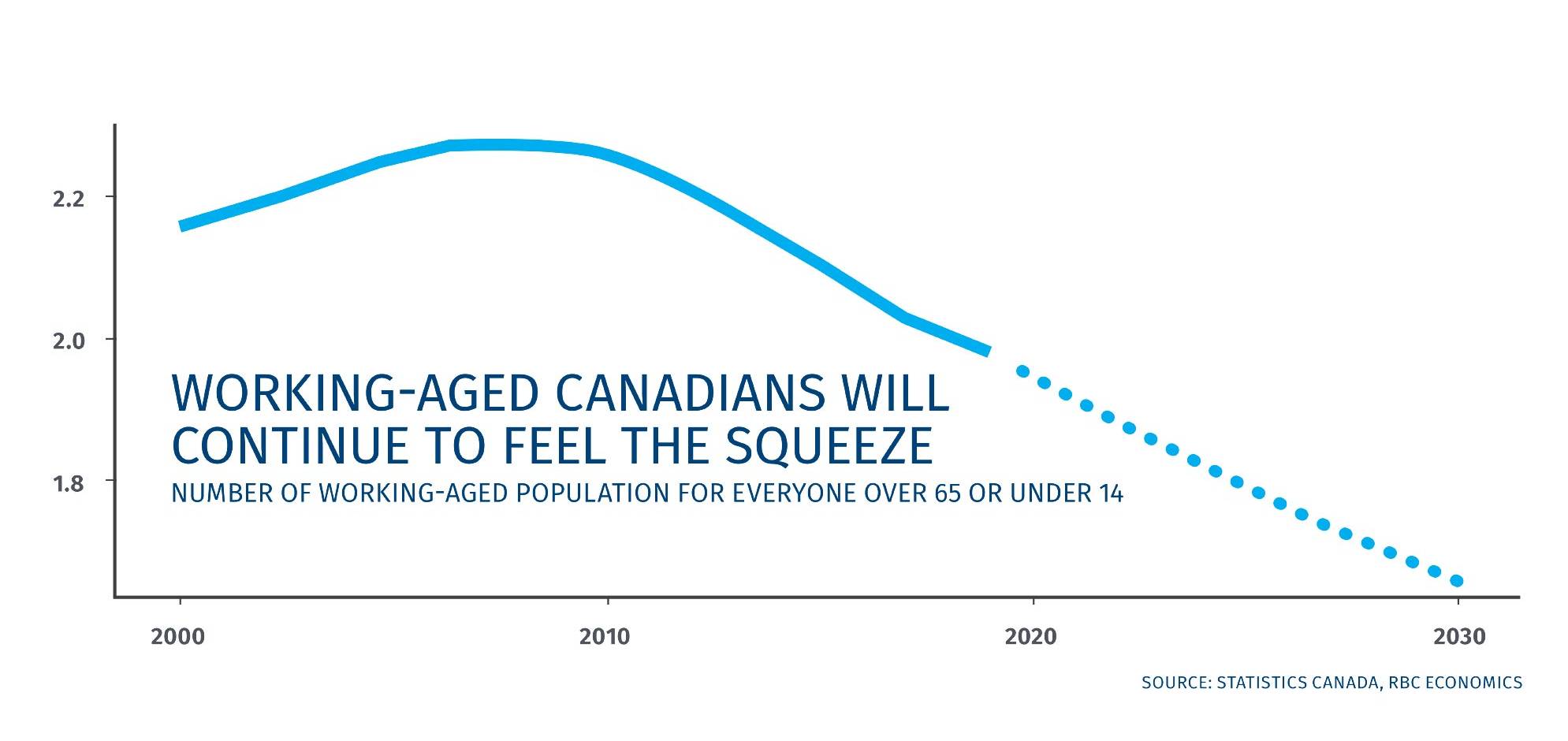

Aging is likely to transform our society in significant ways—from increasing demands on our healthcare system and changing the types of housing we build, to boosting demand for group leisure travel and seniors-friendly sports. We may not be able to predict all of the consequences at this stage. But one thing’s for sure: working-age Canadians will feel the financial squeeze. There will be fewer of them to shoulder the additional costs of our aging society. In 2010, there were 2.3 working-aged Canadians for every youth and senior. By 2030 we expect that number to fall to 1.7. The slowing growth of the labour force (which will actually cause the participation rate to fall from 65% today to 62% by 2030) will be a problem for governments, who will have to shoulder an increased burden.

While Canada’s strong rate of immigration will help offset those pressures, supporting and caring for a larger number of older Canadians will be a primary theme of the 2020s.

Costs of care could crowd out other spending initiatives

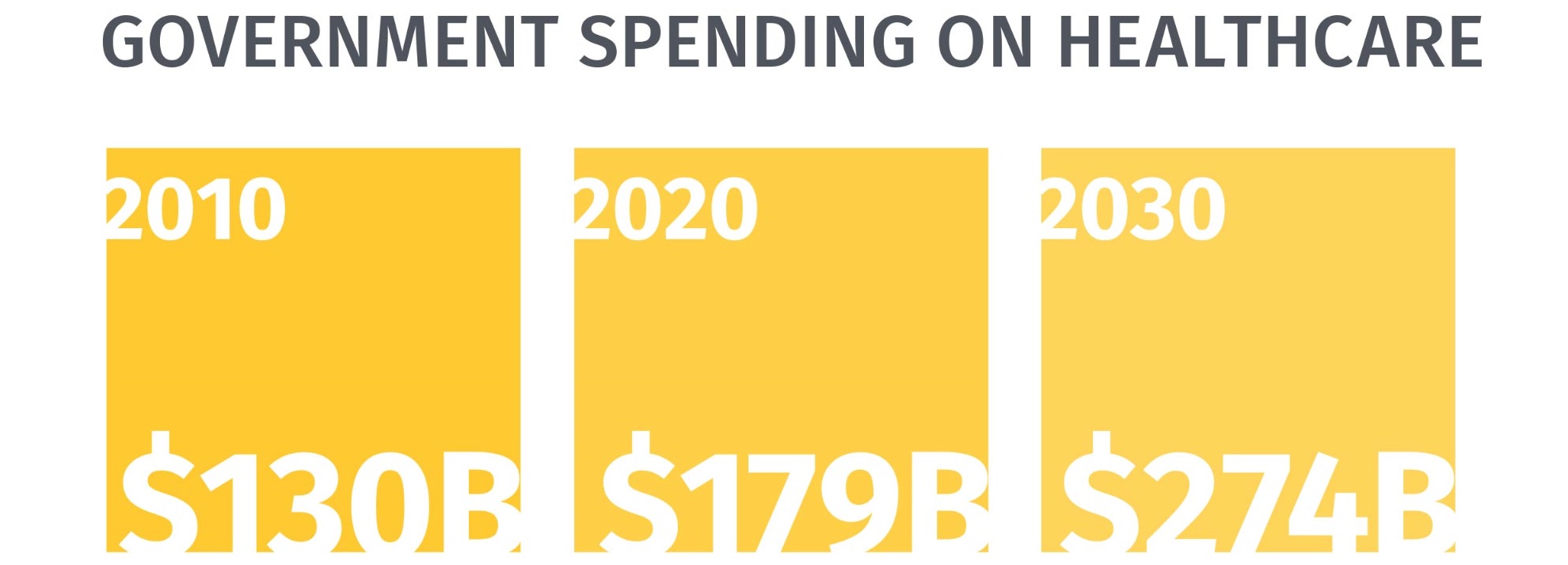

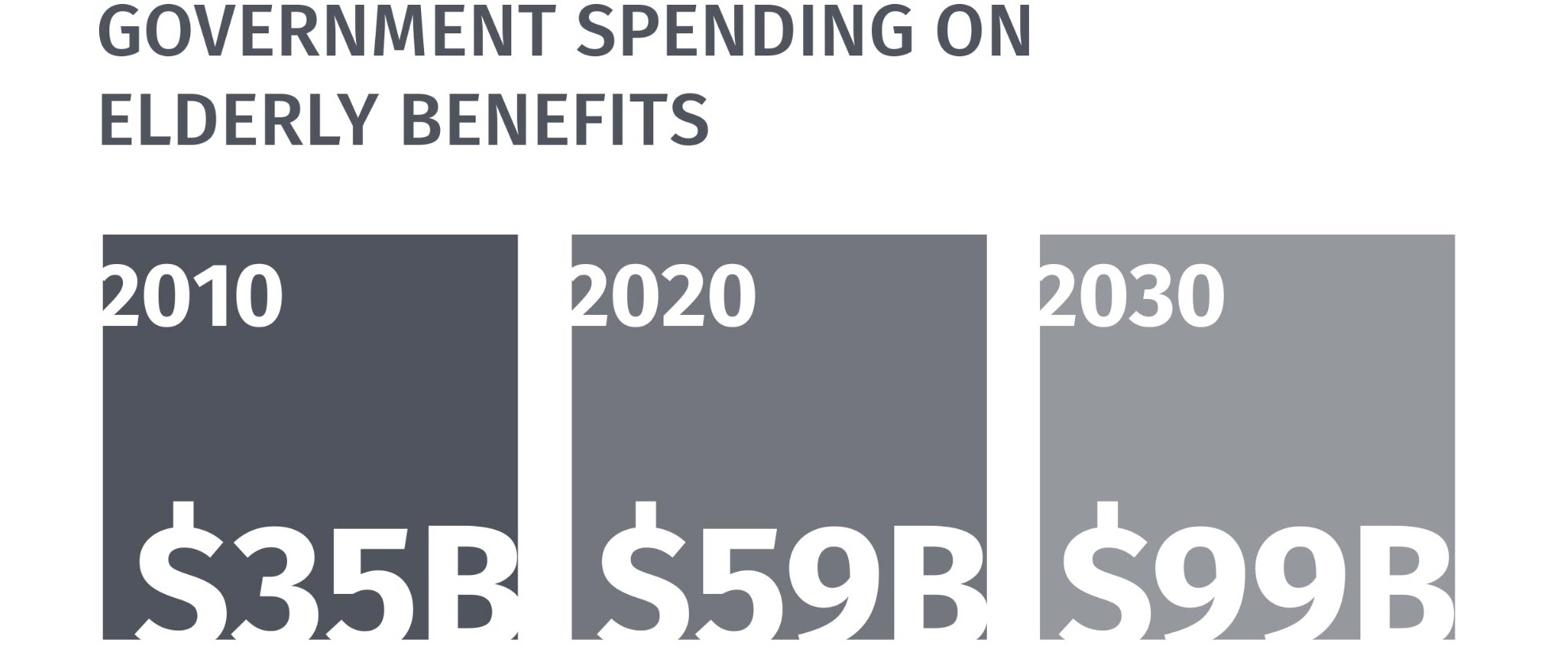

The financial demands of an older population will make it harder for governments to fund key growth priorities like education and skills development, let alone the vote-getting niche initiatives they often advance at election time. All levels of government will feel pressure from a shrinking tax base. Caring for seniors will consume 55% of provincial and territorial healthcare budgets in 2030 versus 45% now. Demand for long-term care beds alone could cost the provinces $50 billion in construction costs by 2035.

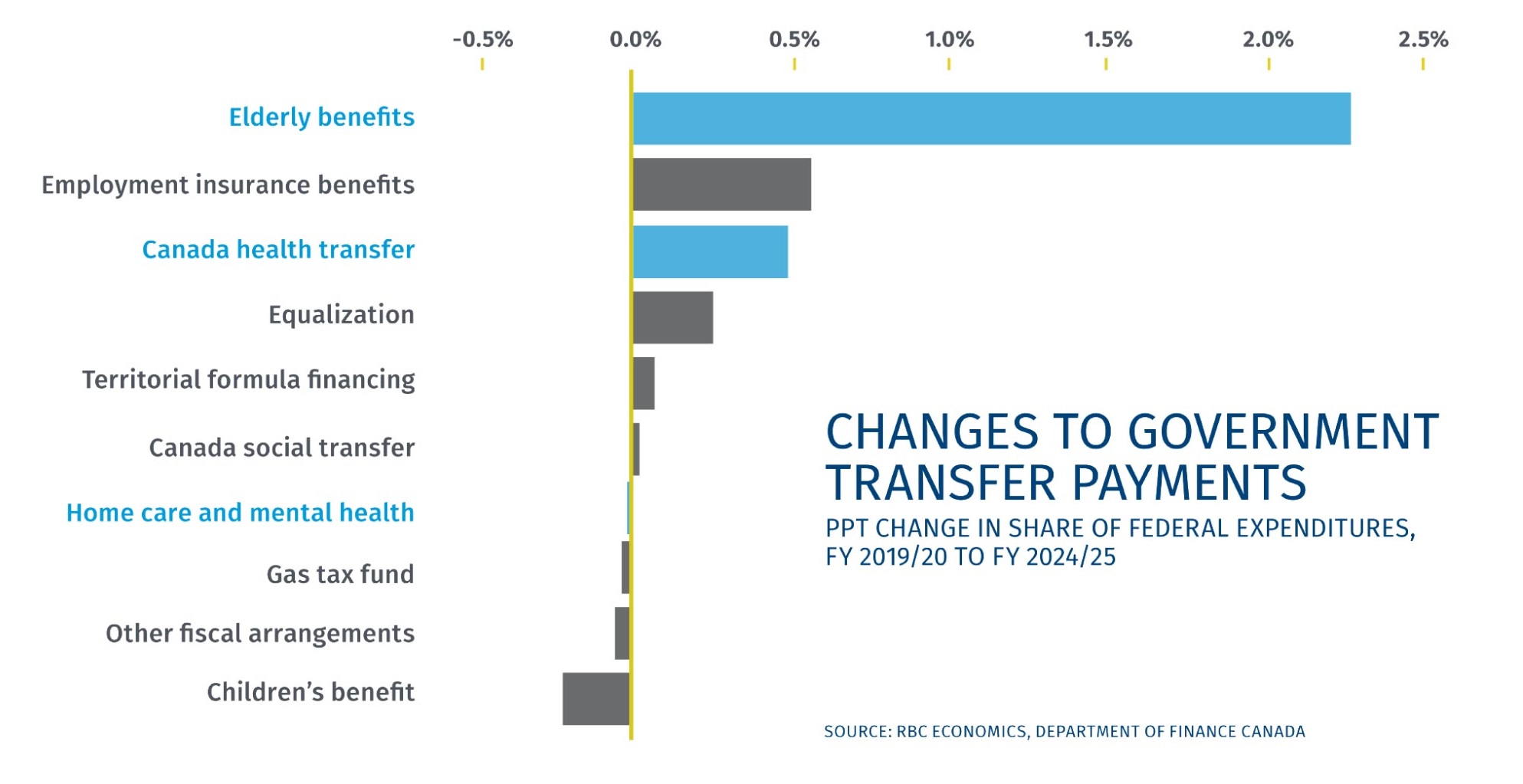

Ottawa, meanwhile, will face pressure to boost its transfers to the provinces to help them prepare for the realities of the 2020s. At $76 billion, and growing 3.6% a year, transfers to the provinces currently consume more than 20% of Ottawa’s budget. Public debt charges will add to the strain.

A national challenge: Finding homes for aging Canadians

In 2020, 45% of baby boomers will be 65 and over, with the others joining their ranks over the decade. By age 80, one in 10 will be living in a seniors’ residence or nursing home, a number that will jump to one in four by the time they’re 85.

There will be about 650,000 people living in Canadian seniors’ residences or nursing homes in 2030, up from 450,000 now. Public and private resources needed to build the extra capacity will cost at least $140 billion.

The Opportunity

Building for the future

One of the defining characteristics of the last decade was worsening housing affordability, both for homeowners and renters. This is likely to persist in the 2020s, especially in Canada’s largest cities, as strong immigration levels drive demand for housing. The steep cost of housing will make more of us renters—up to 1 million more, by our count. It will also fuel the growth of smaller housing markets beyond the more expensive cities, where younger Canadians have a better shot at buying their first home. The overall home ownership rate in the country is likely to fall from almost 68% in 2016 to 64% by 2030.

Canada’s aging population will offer an opportunity to address some of the country’s housing challenges. Over the coming decade, we expect baby boomers to ‘release’ half a million homes they currently own—the result of the natural shrinking of their ranks, and their shift to rental forms of housing, such as seniors’ homes, for health or lifestyle reasons. Downsizing boomers will put even more units on the market.

The homes baby boomers put up for sale—often units well suited for families bought decades earlier near urban cores—will be long-awaited supply for new generations of buyers. If the price of these properties will be hard for first-time homebuyers to swallow (baby boomers won’t sell cheap), the turnover will bring opportunities for others to add to, and transform, the housing supply. For example, multiple units could be built on a lot previously occupied by one dwelling. Just the kind of gentle increase in density that many see as a key part of the housing affordability solution in Canada’s largest cities.

To maximize this transition, though, more progress will be needed to modernize zoning bylaws and other restrictive housing supply policies—complex and emotionally-charged issues to say the least. More than anything, this modernization will be critical in the decade ahead for new generations of Canadians to realize the same housing dreams as their baby boomer elders did decades ago.

3. Smarter

The Challenge

Canada’s economy is being reshaped by technological advancements, with the digital economy growing by 40% over just seven years. Digital platforms facilitate financial transactions, the consumption and production of entertainment services, and serve as a marketplace for goods. Those activities, along with the software, infrastructure and support services that facilitate their delivery, now account for 5.5% of the country’s GDP, employing close to 1 million Canadians. And the digital economy is highly productive, with GDP per worker running 16.5% faster than the overall economy.

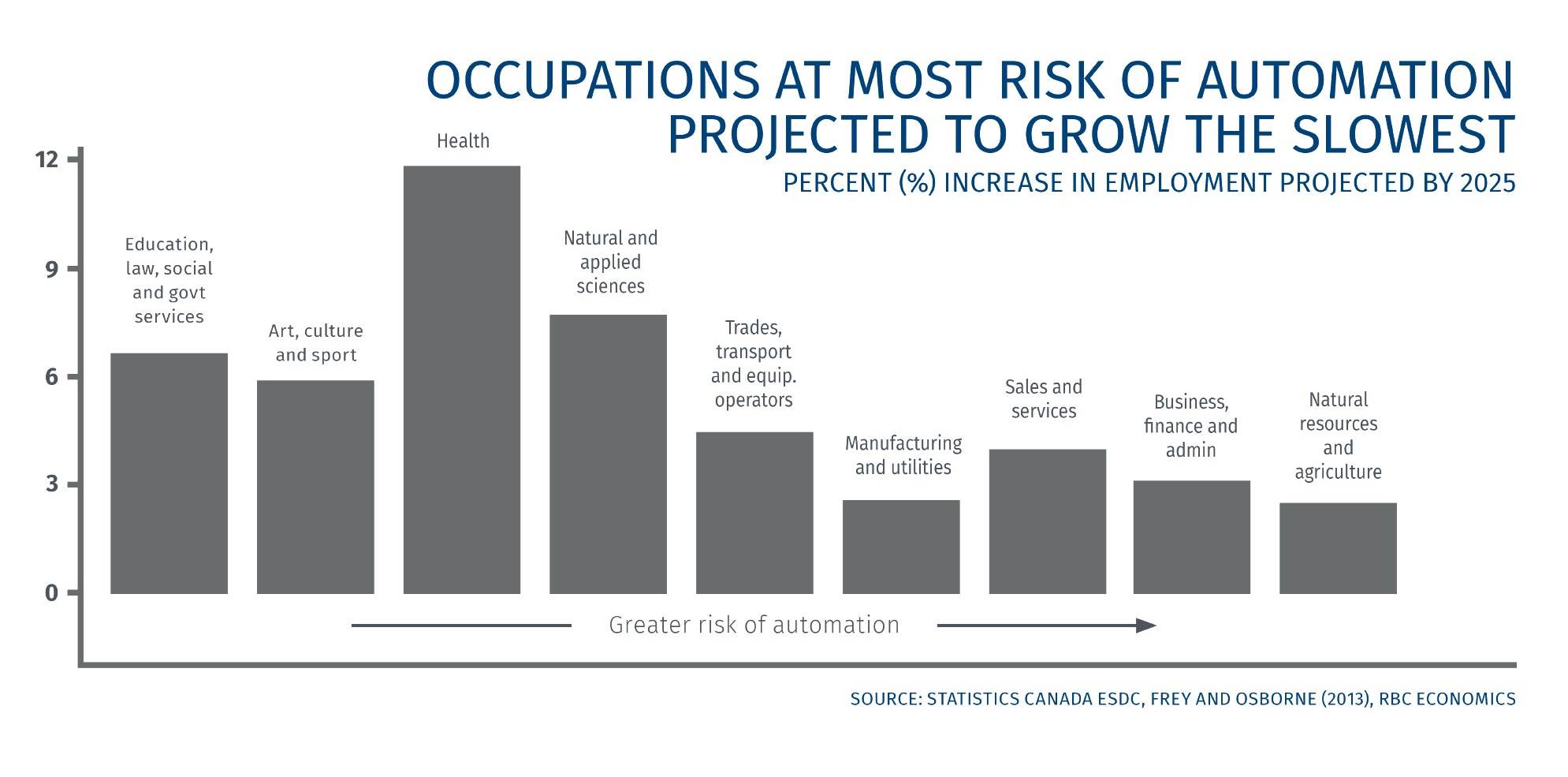

While the digital economy is expected to add millions of new jobs and create opportunities in all sectors, it will also cause dislocation. More than a quarter of Canadian jobs are at risk of disruption in the coming decade. The challenge will not only be to help those currently facing disruption in their own industries and occupations, but also to help the next generation of Canadian workers adapt to a changing labour market. A recent survey of Canadian employers by the Canadian Federation of Independent Business found that 42% of small businesses cite a shortage of skilled workers as their largest business constraint—ahead of both insufficient demand or lack of working capital.

As we have argued in our Humans Wanted research and elsewhere, investing heavily in human skills that complement technologies such as machine-learning and artificial intelligence will go a long way to closing the 20% gap in labour productivity between Canada and the rest of the G7.

The Opportunity

Powering the knowledge community

The countries that do the best job of creating, accumulating and exporting knowledge are likely to prosper in the 2020s. The global race to lead in areas including AI and supercomputing has already begun. Ottawa has responded by funding innovation superclusters and other initiatives – its Innovation Superculsters Initiative aims to add $50 billion to GDP by 2030. Canada can already claim some success: our cities have large concentrations of AI startups and have also received significant investment from global tech giants. The first half of 2019 saw record venture capital investment of $2.15 billion in Canada, with information and communications technology accounting for 54% of dollars invested.

Build the skilled trades pipeline: Skilled trades are still in high demand. Canada needs to keep building the pipeline of people going into skilled trades, encourage tradespeople to be more mobile and increase the numbers of those with national certifications.

Our task this decade will be to build on that early head start. We already have a strong foundation in the form of a highly educated, flexible and dynamic workforce and a growing services sector. Educators, employers and policymakers are turning their attention to ensuring our workforce has the skills needed for the economy of the future, but about 40% of Canada’s postsecondary students don’t currently have access to work-integrated learning opportunities. More investment to help innovative firms commercialize their products and scale up will be required. We’ll also need to retain more of the ideas developed here.

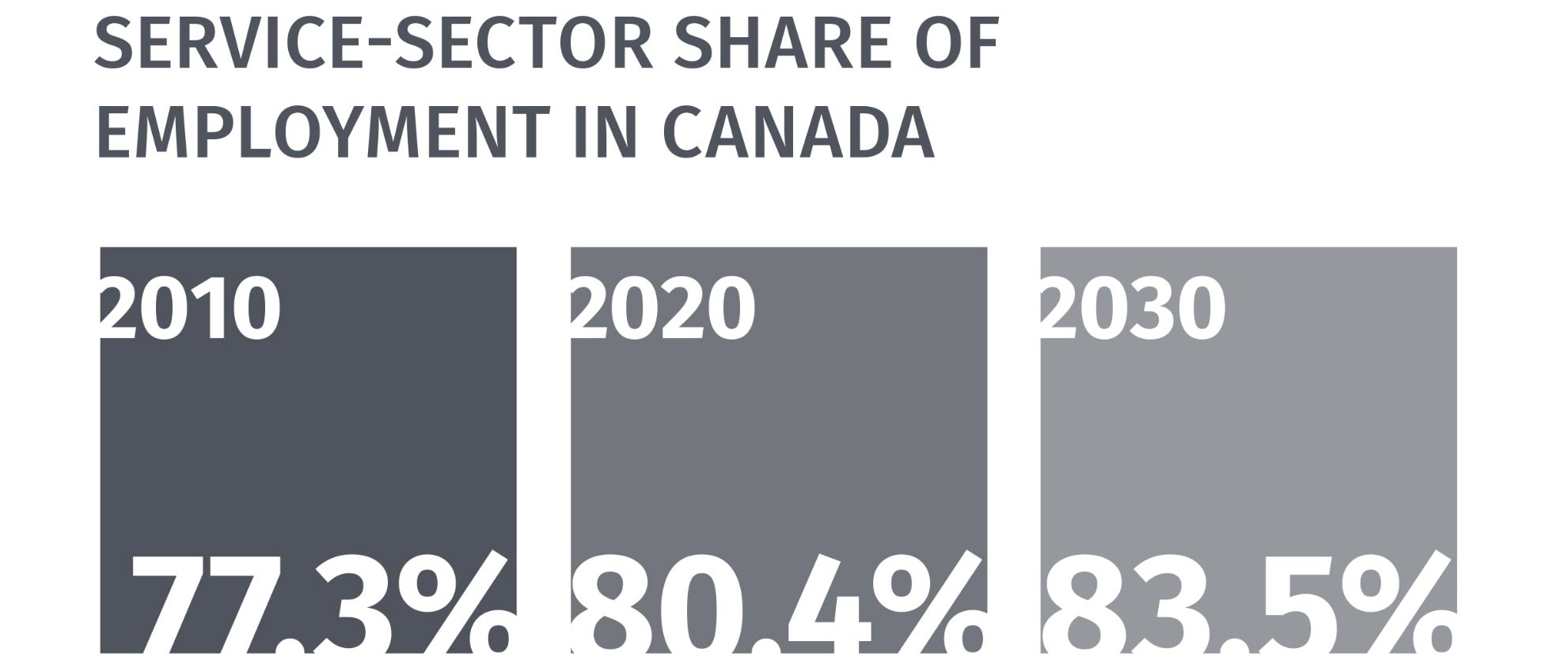

A thriving services sector will support Canada’s growth

2019 was the year the services sector demonstrated its resilience. That’s important, given its growing clout globally as the automation of goods production expands. Services output accounts for around 70% of our GDP, up from around 50% in the 1960s. Services’ share of the overall economy will keep growing.

Despite a (mostly undeserved) reputation for low pay, nine of the top 10 industries in terms of employment growth have been in the services sector for more than a decade, and the fastest-growing— the professional, scientific, and technical services industry—pays wages well above average.

Service-sector jobs tend to be more resilient to short-run ebbs and flows in the economic cycle. Consider this: employment in private service-producing industries declined less than 2% in the 2008-2009 recession; the drop in the goods sector was closer to 8%.

Leveraging our human capital

Immigration will be a powerful antidote to our aging society. It’s well known that we possess the highest foreign-born population among G7 nations. Perhaps less well known: immigrants are keeping us younger. If we’d halted immigration in 2006, Canada’s median age would be 42.7 years instead of 40.8 as it is today.

Our research indicates that, while we do a great job of attracting immigrants, we could do better in integrating them into the Canadian labour force. Immigrants earn about 10% less than those born in Canada. The gap spans occupation, age, gender and region. Bringing immigrants up to the wage and employment levels of those born in Canada could add $50 billion to GDP, our research shows. How to get there? Devoting more resources to helping immigrants transition into the labour force after they arrive in Canada, and helping Canadian employers better assess foreign work experience.

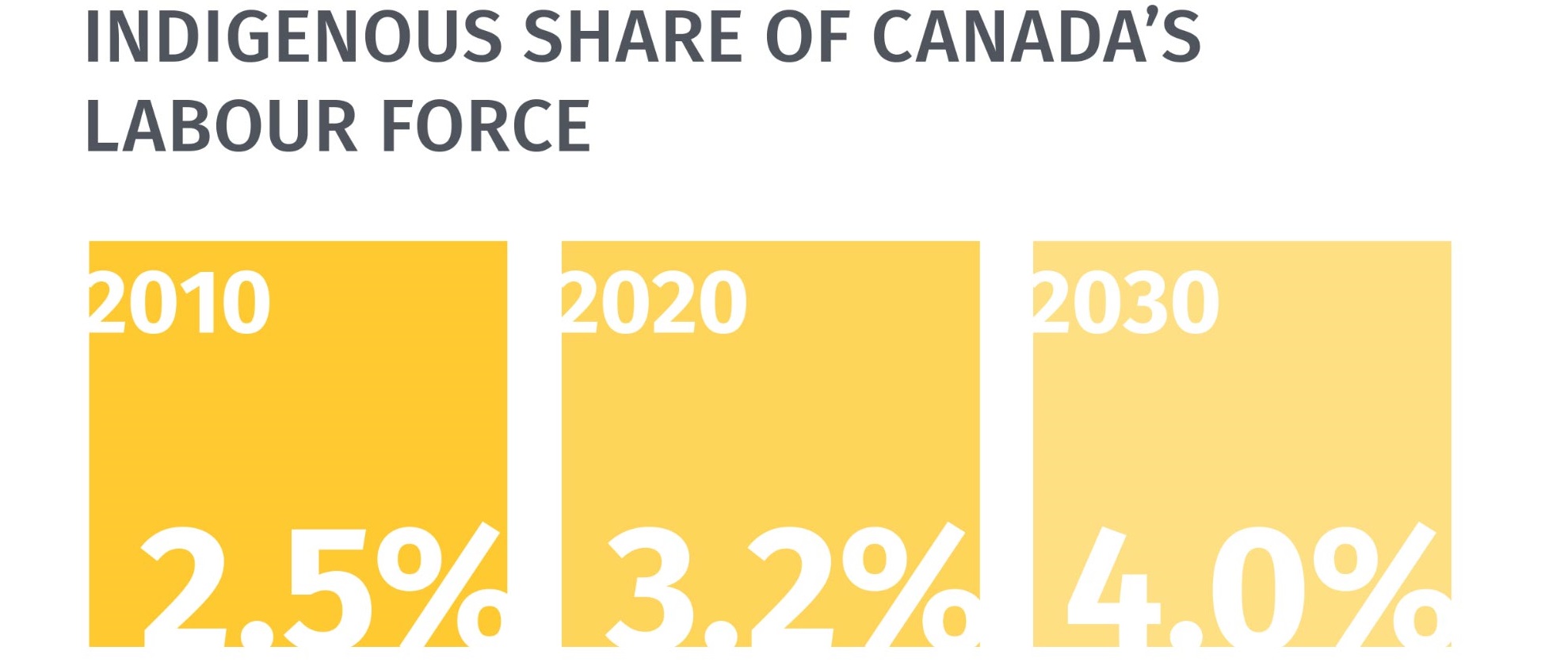

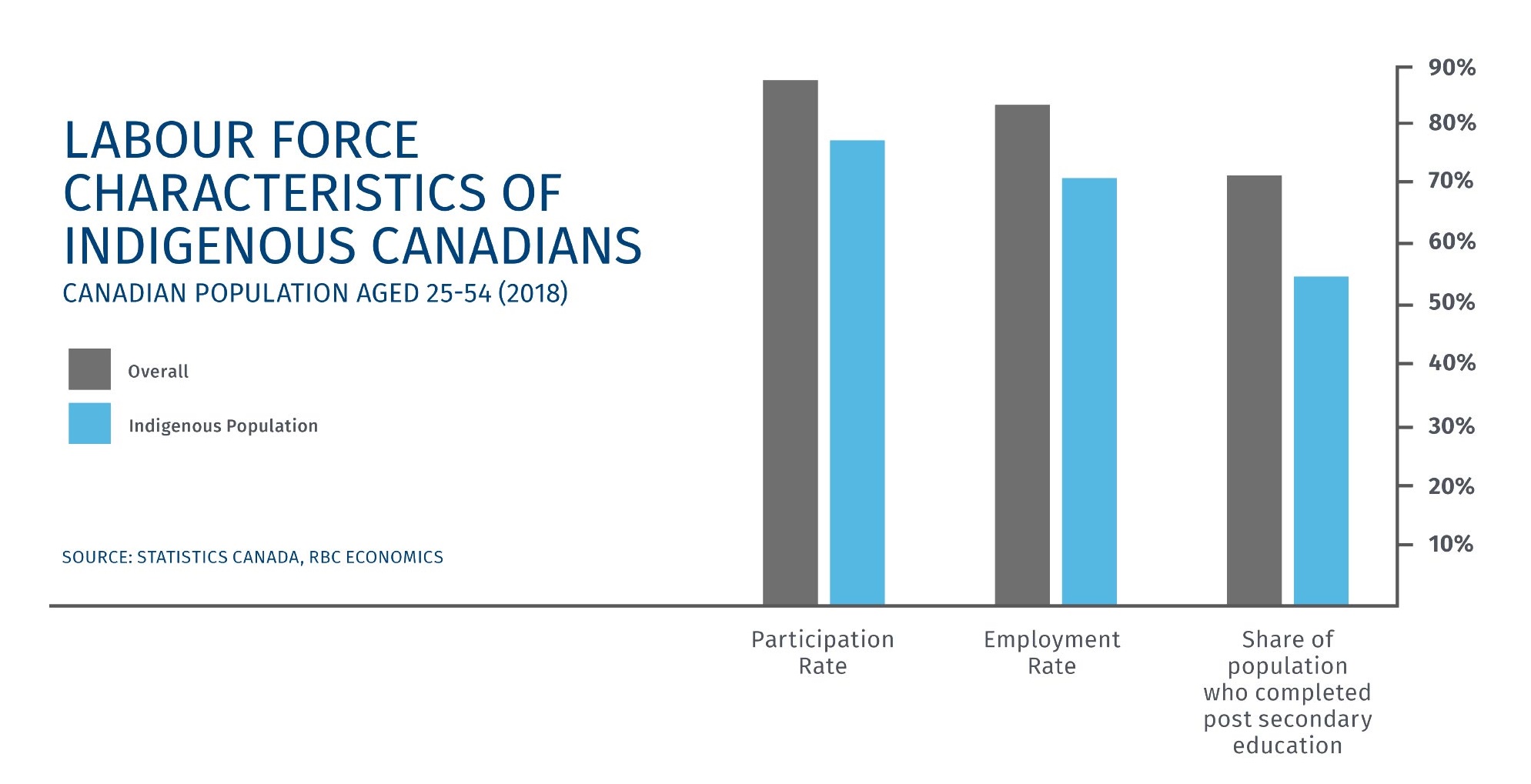

Immigrants aren’t the only ones whose potential isn’t being fully realized. Indigenous Canadians, whose share of the overall population is also increasing, fall short on key labour market measures including participation in the workforce. And women, who’ve made significant earnings gains in recent decades, still only lay claim to about 40% of the total wage pot. Narrowing these gaps and helping these cohorts share more fully in our prosperity will help Canada’s economy thrive.

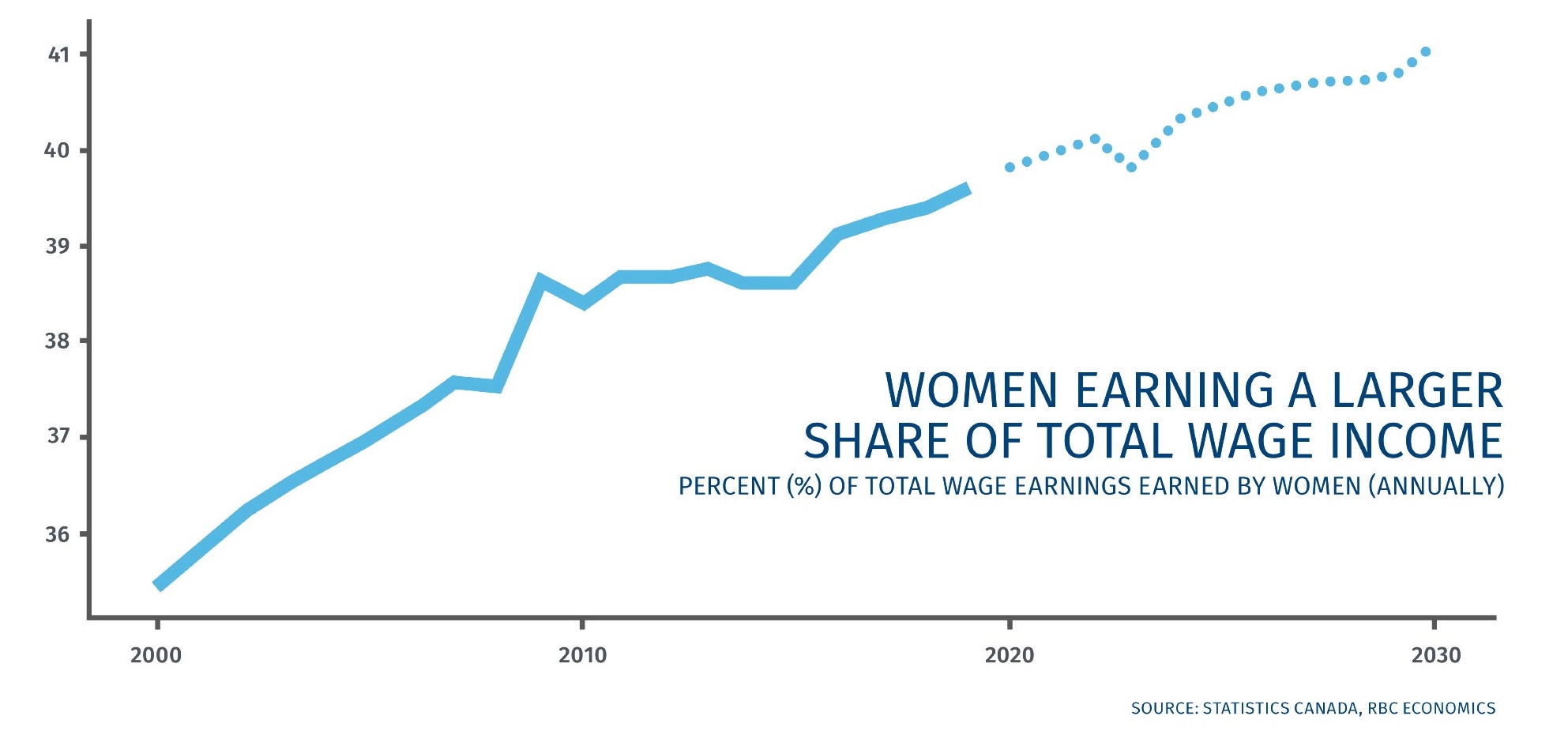

Closing the participation gap for women

Canadian women have seen significant gains in the labour market over the past two decades, increasing their share of wage income from 35% to nearly 40%. Much of these gains came as younger cohorts, particularly millennial women, became more educated and attached to the labour force than their older counterparts. As older women continue to exit the labour force through retirement, and millennials enter their prime earning years, the share of earnings earned by women is expected to continue to increase.

Getting more women into the trades: The Canadian Apprenticeship Forum has identified millwrights, welders and heavy-duty equipment technicians as trades where the supply of trained workers will be in the greatest imbalance over the next three years. Age is a factor, but so too is gender, with men holding 98%, 93% and 99% of jobs, respectively.

However, over the next decade, these gains are likely to be relatively modest—increasing only to 41% by 2030. Over the past 10 years, the employment-rate gap between men and women aged 25 to 44 has remained stubbornly between 7 and 8 percentage points, illustrating how even as some pay inequities have been addressed, women are still a long way from escaping the asymmetric costs of raising children. And as the population of seniors increases rapidly, women who have traditionally been tasked with providing care—54% of caregivers in Canada are women—may see a disproportionate strain placed on them in the coming years.

Equalizing participation rates of men and women in the labour market could yield a 4.9% increase in GDP. Solutions may be found in pockets such as Quebec. The province implemented a $5 per day daycare policy in 1997, which is largely credited with raising employment rates of women from 2 percentage points below the national average in 1995 to 4 percentage points above it today. We may require bold new policies such as this to support those caring for elders in order to ensure that progress for women doesn’t stall.

4. Slower

The Challenge

Aging will drive another trend of the 2020s: slow economic growth. Due to lackluster growth in both productivity and the labour force, we expect only modest growth in the economic pie. Indeed, if productivity growth continues at the recent 10- year average of 1%, we’re likely to see the Canadian economy expand at a modest rate of 1.5% to 2% a year during the 2020s. That’s about a percentage point below estimates ahead of the Great Recession, and that percentage point gap adds up to an economy that’s almost $250 billion smaller in 2030 than it would have been if earlier trends had held.

Canada’s long-run structural growth challenges are not unique. High rates of immigration mean that Canada’s long-run structural growth challenges actually look somewhat smaller compared to other advanced economies. Canada’s working age population is still expected to grow at almost half a percent per year. That’s far below the rate of growth in prior decades, but it’s still better than most of Canada’s advanced economy peers, including the United States.

As the current economic expansion stretches into year 11, we’re also facing an elevated risk of recession, since downside risks are more numerous than upside ones. Nonetheless, we don’t forecast a recession in Canada in 2020.

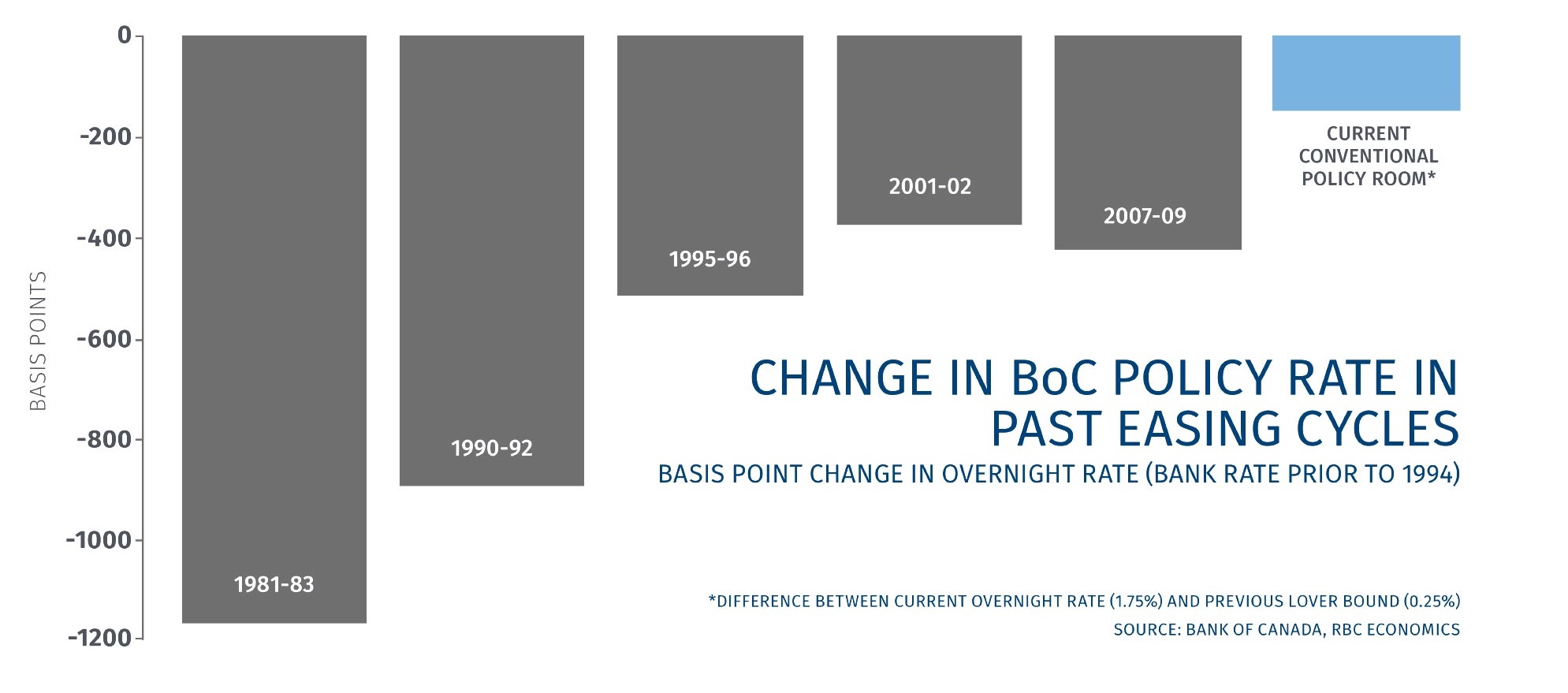

Ultra-low rates will persist

Central banks around the world cut interest rates in 2019 to stoke economic growth. Very low interest rates will be around for a while. Aging and tepid productivity are set to constrain growth in Canada and other countries, softening demand for credit. Ultra-low interest rates have enhanced household wealth by boosting prices for housing and equities. But they’ve hurt savers and pensioners, among others.

The era of extraordinarily low interest rates has forced central banks to become more creative in responding to periods of economic weakness. They’re likely to have to rely even more on unconventional monetary policies, including forward guidance, quantitative easing, funding for credit and negative interest rates, which all may turn out to be less effective than traditional rate cuts.

Freer trade could be harder to achieve

Global trade tensions have given rise to concerns that a more far-reaching shift is taking place: the end of globalization. A surge in trade agreements and the global flow of goods and services over the past three decades has reshaped the world economy, and expansion of cross-border supply chains has boosted productivity and enhanced Canadian prosperity. A longer-term, global turn away from freer international trade would clearly be negative for a relatively small open economy like Canada’s. A recent trend toward countries striking bilateral trade deals rather than multilateral agreements won’t help.

There weren’t many formal regional free trade arrangements before the formation of the WTO in 1995, meaning some of the trade deals that came in the years to follow were akin to plucking low-hanging fruit. The pace at which new regional trade agreements were being struck had already begun to slow before the Brexit vote or the election of Donald Trump, and that’s likely to persist. And the boost from innovations in transportation and the entrance of major emerging markets into the global trading system that were seen in the 1980s and 1990s were positive shocks that probably won’t be repeated in the medium term.

The Opportunity

Staying open to the world, and each other

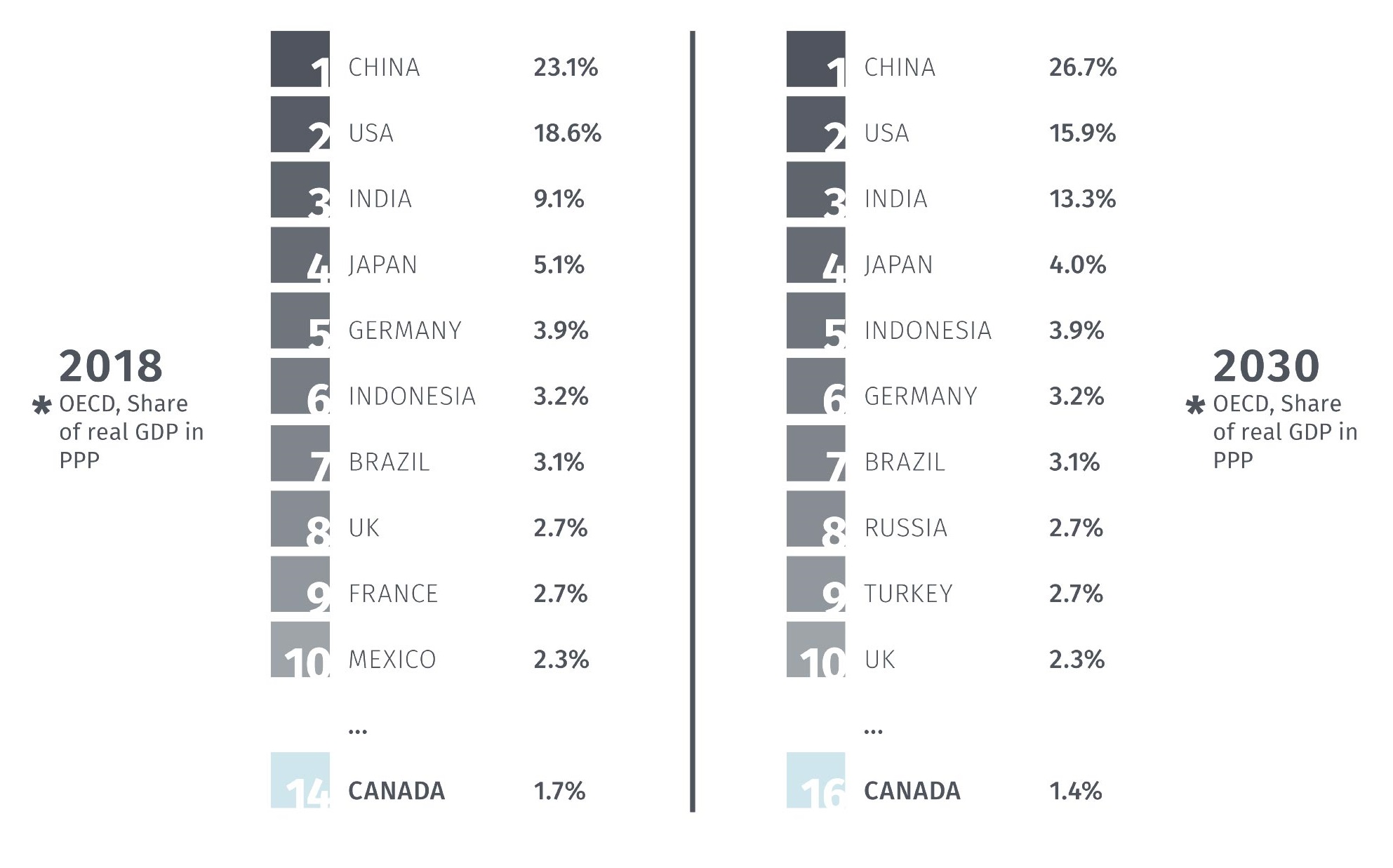

Canada’s share of real global GDP is set to fall to 1.4% in 2030 from 1.7% now, the OECD predicts. It will be imperative to look beyond Canada’s borders for growth opportunities. While the U.S. is set to remain our biggest export customer, it too will likely account for a smaller share of global output, with India and China continuing to capture greater shares. However, there are countries that will see even faster growth than China in the coming decade. Among them: Bangladesh, Vietnam and Kenya.

Canada’s challenge will be to leverage its existing strengths—for instance in agriculture, where we have a significant opportunity to capture a larger share of global agricultural exports. And to develop new ones. Despite our world-leading educational attainment, we still are not a top exporter of ideas.

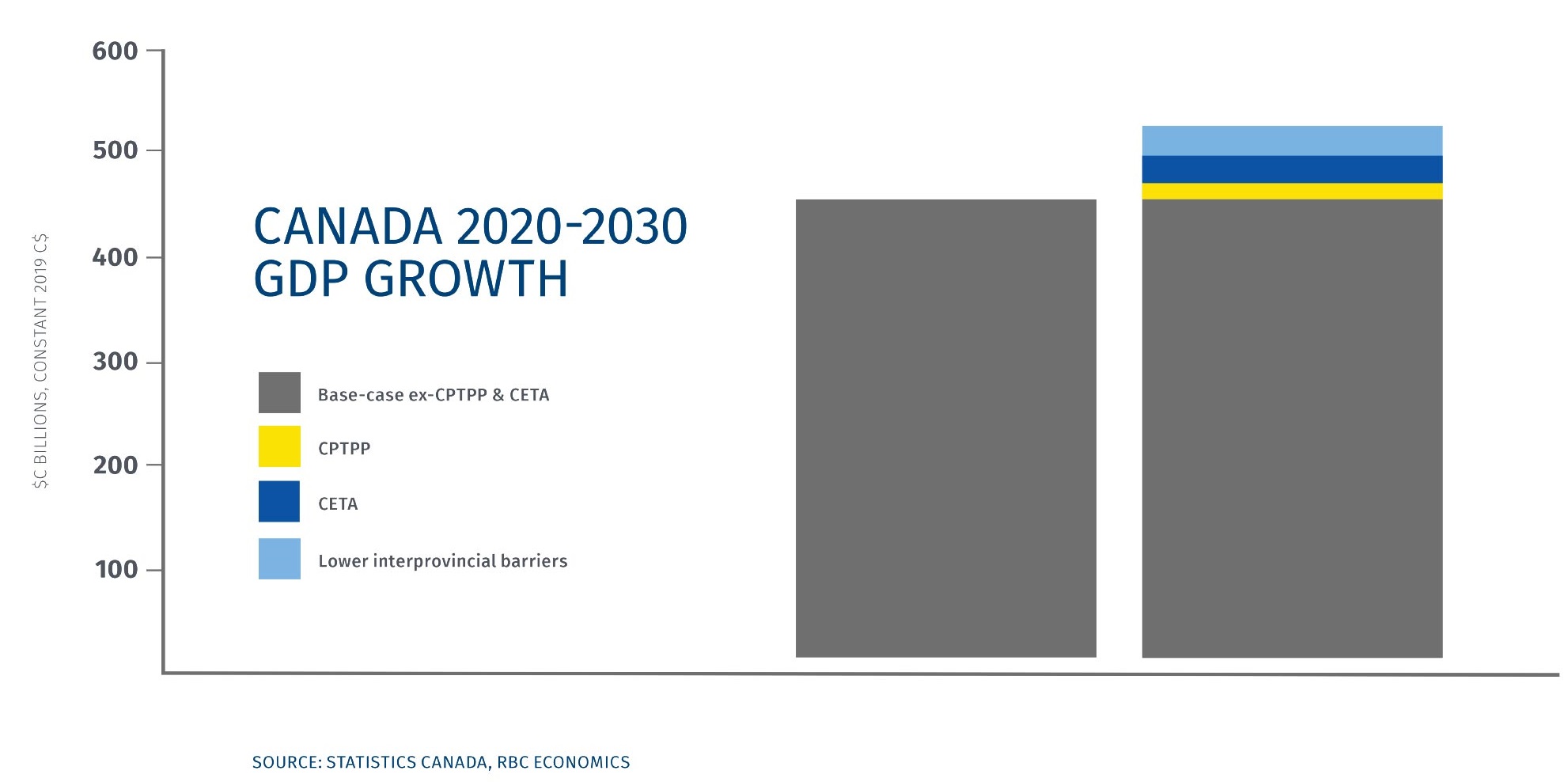

Free trade deals can offer growth at the margins

While there are diminishing opportunities for global free trade deals, Canada still has something to gain from championing free trade. In the last three years, it pushed forward new trade deals with the European Union (CETA), Pacific Rim countries (CPTPP) and Ukraine. These agreements will add about 0.5% to GDP in the years to come. Even marginal gains are important in the face of rising domestic growth headwinds from an aging population.

Made-in-Canada freer trade

Even as Canada champions external free trade, there’s a domestic solution that could pack more economic punch. Just 20% of SMEs in Canada sell to other provinces. Reducing interprovincial trade barriers by just 10% could boost GDP by 0.6% over three years, according to the Bank of Canada—a bigger impact than CETA and CPTPP combined.

The 2017 Canadian Free Trade Agreement between the federal, provincial and territorial governments was a step in the right direction. Since then, Alberta trimmed its list of CFTA exemptions last year, and now has the fewest restrictions to interprovincial trade.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More