Proof point: High rates of population growth thanks to immigration in Canada have helped to blunt the substantial costs of an aging population even though it’s created other economic challenges.

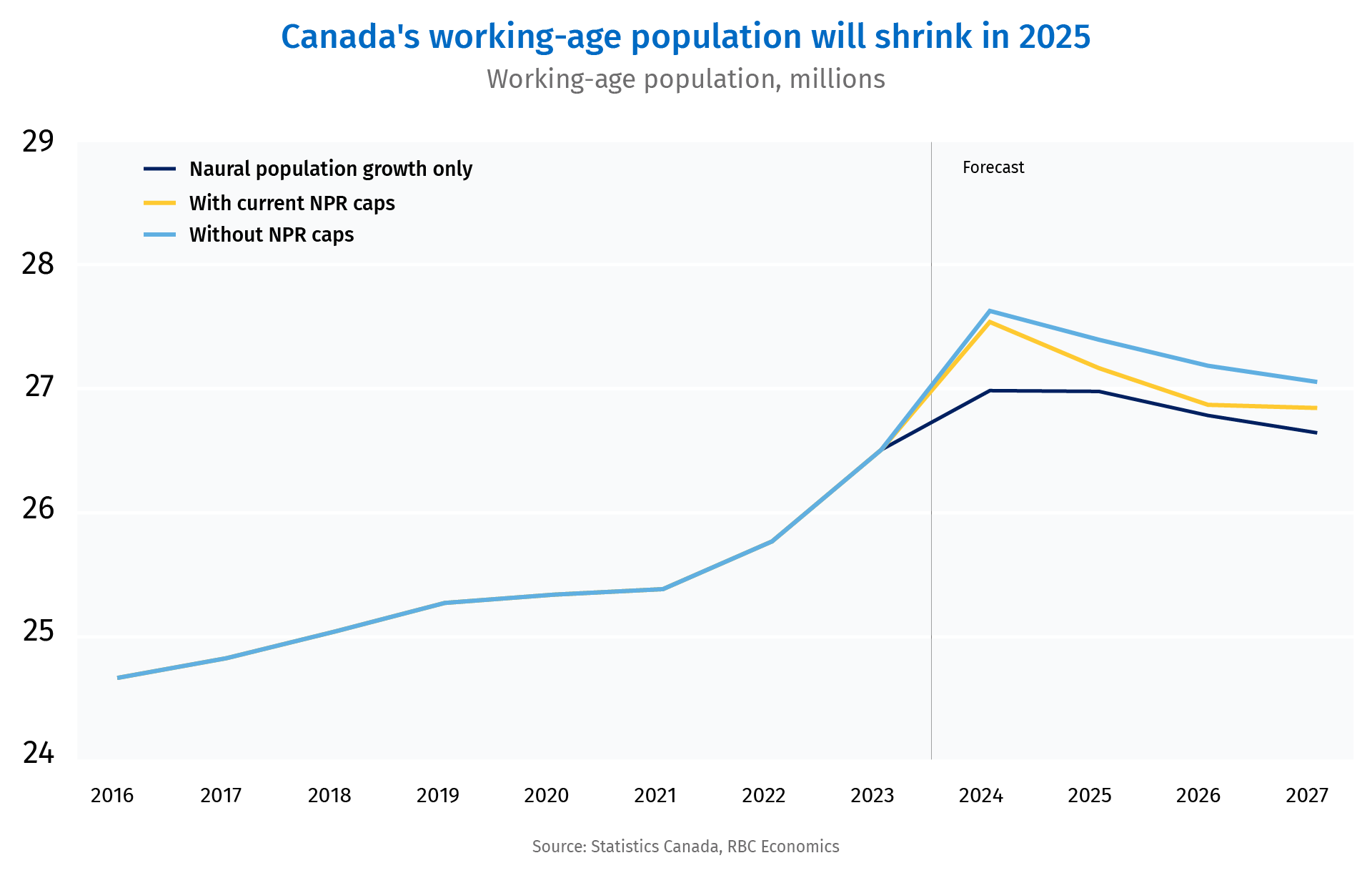

- Canada’s non-permanent resident caps are set to curb ballooning population growth. The population will be at least 2.5% smaller in 2027 than it would have been without the restrictions on non-permanent residents.

- But even with the caps in place, Canada’s population will continue to grow. The migration rate is nearly double that of the United States.

- Immigration has long been viewed as a strategy to slow the pace of population aging since immigrants, on average, are younger than the existing population.

- Canada’s age-related unfunded liability was sized at $70,000 per person by the C.D. Howe Institute in 2018, significantly smaller than the U.S. at $236,000 on a per-capita basis.

- Even with immigration caps in place, the hit to Canadian finances from an aging population will be much smaller than in other countries, because of migrants.

Canada’s recent cap on non-permanent residents along with a limit on international study permits is indicative of a broader shift in public attitudes towards immigration. The goal of recent policy measures has been to respond to concerns about Canada’s ballooning population including its impact on housing affordability.

But, reducing immigration also has longer-run economic costs. The Canadian population—like many advanced economies— is getting older. The share of the population that is over age 65 is increasing rapidly as the large baby boom generation flows through to retirement. An aging population means the share of the population that is retired is rising, even though people are working longer than they used to.

That also implies a larger and rising share of the population is no longer working but still consuming. This creates a mismatch between consumer demand and the amount of goods and services the economy can produce. It will add to structural labour shortages, higher price pressures, and structurally higher interest rates in the economy. It also creates a large government funding gap as income tax revenue growth slows while demand for services, particularly for things like healthcare, accelerates as the population gets older.

Immigration makes the population younger

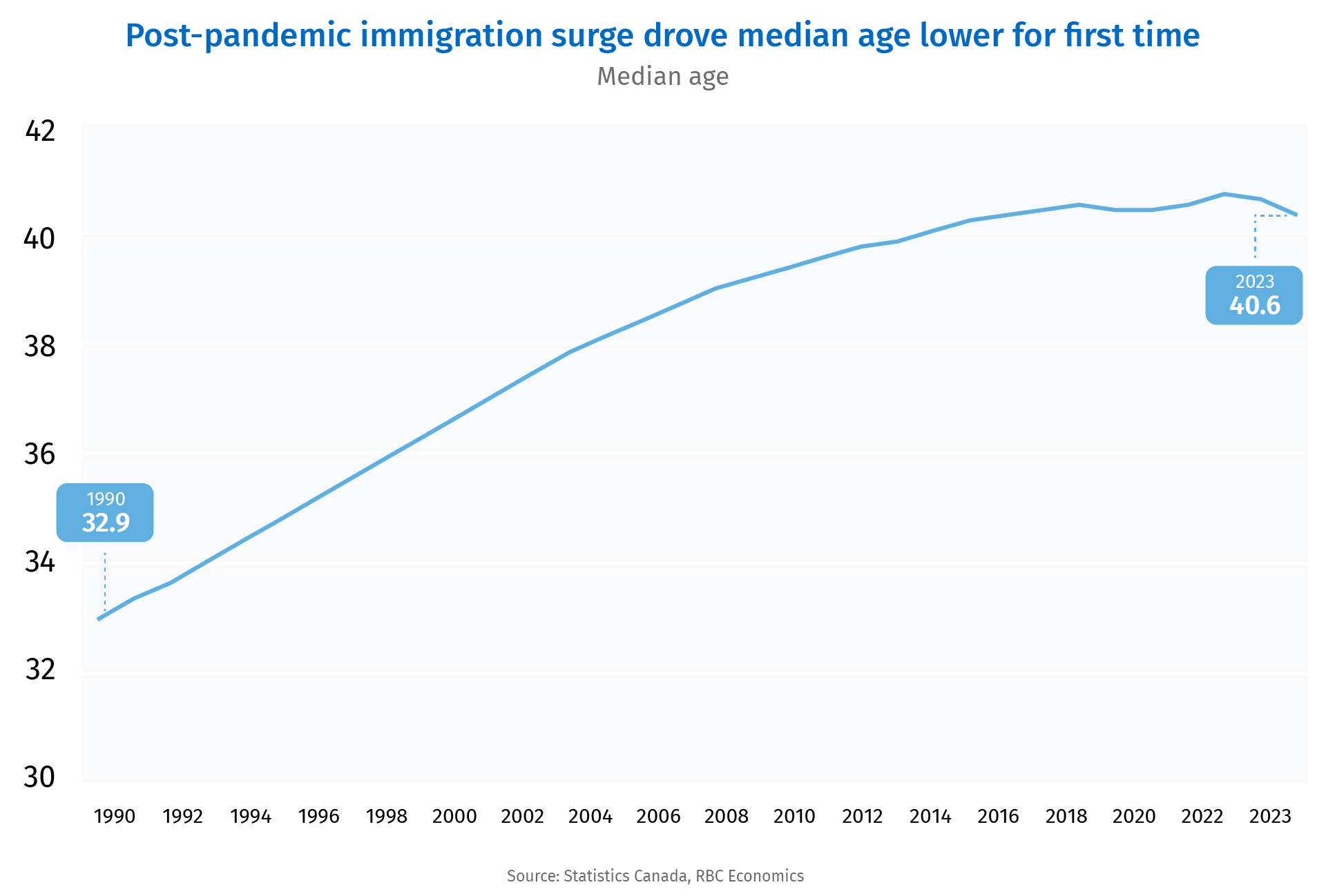

Immigration helps to bend that population age curve because new immigrants, on average, are younger than the existing Canadian population. The average Canadian is 42 years old, while the average newcomer (either permanent or non-permanent resident) is more than a decade younger at age 28. After the pandemic, a surge in new arrivals drove Canada’s median age lower for two consecutive years in 2022 and 2023 for the first time on record back to 40.6.

While the new non-permanent resident cap will not put an end to population growth, it will curb its pace and speed up the aging of the population, even if only by a little. Canada’s pace of population growth was already expected to slow to 1.6% between 2025 and 2027 from annual growth above 3% in recent years. The new non-permanent resident cap will slow growth even more to average 0.8% over that time period. That may sound small, but it amounts to nearly 1.1 million fewer people in Canada by 2027. That’s a 2.5% reduction from population growth forecasts before the caps were introduced. The cap will translate to a 0.9% reduction in the size of Canada’s working-age population and boost the dependency ratio to 58.9% by 2027. The ratio—the number of dependents (aged zero to 14 or 65 and older) per 100 working-age people (15 to 64)—is up 0.5% from projections before the caps.

Not addressing aging population can be very costly

Canada’s immigration growth has been faster than in most advanced economies, but trying to bend the age curve via immigration is not the only possible way to address an aging population. Canada was proactive in the 1990s at pre-emptively increasing Canada Pension Plan contributions and establishing the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), so that the national pension system is, at least, fully funded.

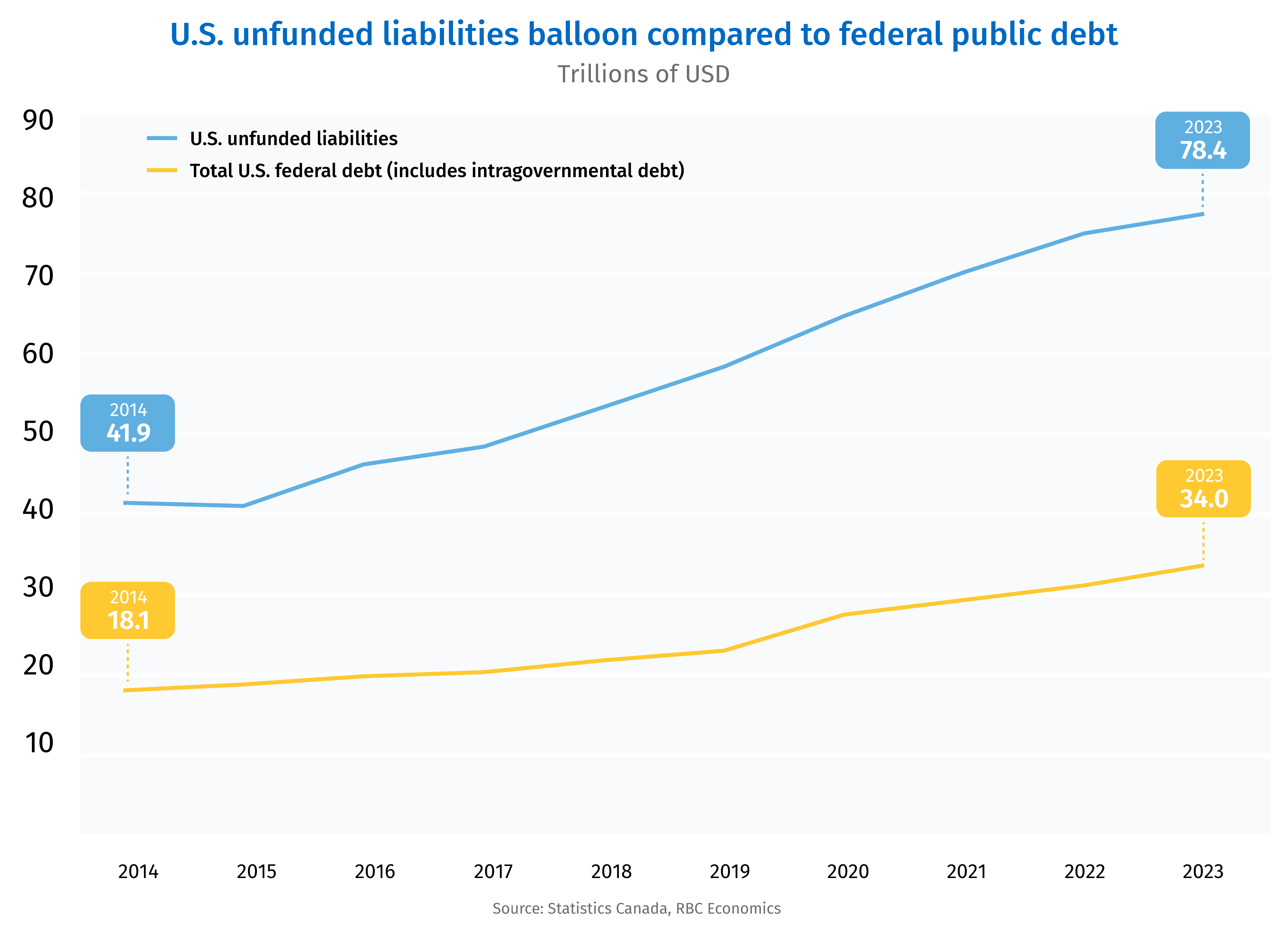

The reality is that an aging population does create substantial costs for an economy that need to be paid at some point. Not being proactive in getting ahead of that curve is effectively passing on the costs to future taxpayers. The U.S. has not been addressing a long-expected shortfall in its social security program and is also facing dramatically higher healthcare costs as the population ages. These are mandatory U.S. federal government programs—essentially a debt made by the American public that will have to be paid by them.

The cost is massive. The current value of future U.S. unfunded liability adds up to just under US$80 trillion, or US$236,000 per person. That is nearly three times larger than the current stock of U.S. government debt held by the public (US$26 trillion) and almost three times the size of the economy.

Canada’s unfunded liability is estimated to be a much smaller fraction—$70,000 per person for healthcare and social assistance, according to a 2018 C.D. Howe report. There are two reasons Canada’s unfunded liability is smaller. First, CPP is fully funded thanks to the introduction of the CPPIB in 1997. Second, Canada continued to ramp up immigration targets, knowing that more newcomers would insulate against a shrinking labour force and its consequences.

In the coming years, Canada can continue to count on immigration to partially offset the effects of an aging population, including a larger funding gap as the labour force naturally shrinks. Countries that have not been proactively targeting immigration to address these challenges will bear the consequences in the decades ahead.

Carrie Freestone is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group and is responsible for examining key economic trends including consumer spending, labour markets, GDP, and inflation.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More