- Canada leads the G7 in attracting immigrants, with newcomers now driving 90% of population growth.

- Immigrants to Canada are better educated and younger than the domestic workforce.

- But they are much more likely to work in jobs requiring less education.

- Better utilization of immigrant skills will be key to economic prosperity, as immigration continues to drive Canadian workforce growth.

- The bottom line: Poor recognition of foreign credentials is the primary obstacle to better utilization of immigrant skills. Eliminating this barrier will be critical to ensuring the Canadian workforce is not only larger—but more productive.

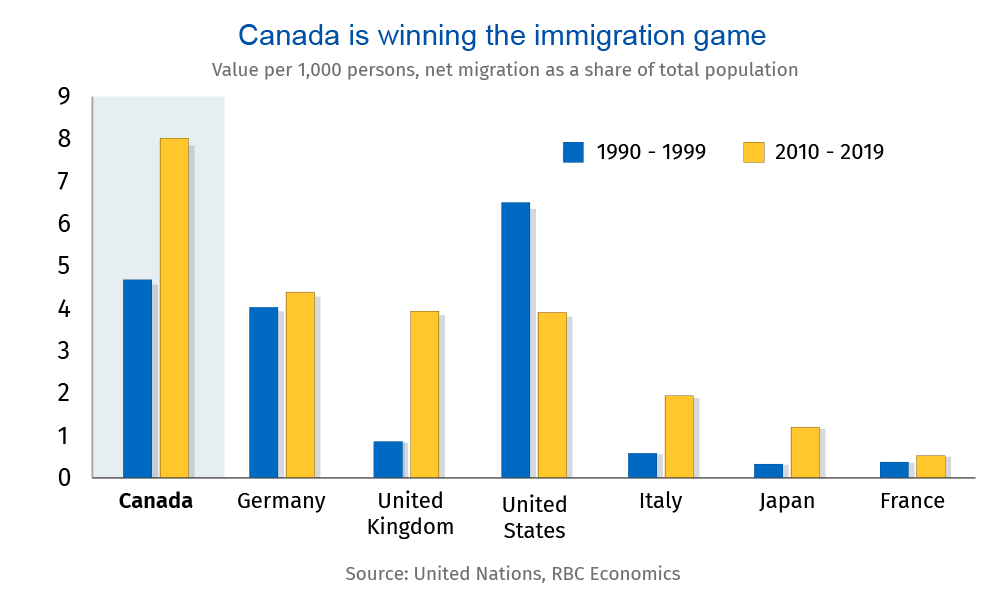

Canada is leading peers in the race to attract immigrants

Few countries are doing a better job of attracting immigrants than Canada. On average, for every thousand people in Canada there were ~8 migrants (when emigration is accounted for) between 2010 and 2019. That’s the highest level among G7 countries—and considerably higher than the U.S., which held the top rate for net migration a couple of decades ago.

Canadian immigration slowed sharply in 2020 due to a variety of COVID-related drawbacks. But its post-pandemic rebound has been powerful. In 2021, nearly 90% of all population growth was driven by higher immigration. And Statistics Canada expects that to reach 100% by 2050. Immigration alone will offset declines from lower birth rates and population aging.

Amid persistent labour shortages, these immigrants are bringing valuable skills. Indeed, of the 1.5 million newcomers that the federal government will target in the next three years, over half will be economic immigrants. That share is considerably higher than in the U.S. or the U.K. (where it sits at about a quarter).

These skilled newcomers (and the stronger workforce growth they’ll bring) are also the main reason we expect Canada’s GDP growth to outpace that of other advanced economies in the coming years thanks to stronger workforce growth.

Breaking barriers to immigrant skills recognition will bear fruit

Higher levels of immigration alone won’t ‘fix’ longer-run structural labour supply issues—but they’ll help. They could help even more if immigrant skillsets were better utilized.

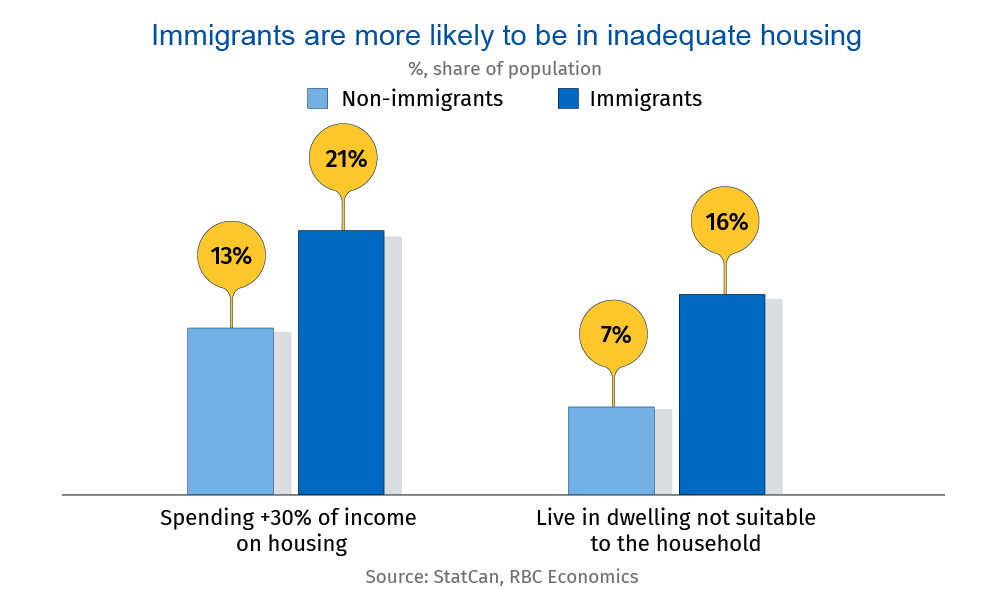

And there are a range of reasons to put them to use. Indeed, new immigrants can fill open positions, but they also increase demand for housing and consumer goods which in turn raises demand for labour. They’re also more likely to live in homes that are not suitable to the size or composition of their household. Better use of skills can offset all of those pressures by making the economy more productive.

As the economy enters a mild downturn due to aggressive interest rate increases and higher inflation, some easing of the labour squeeze is likely in 2023. Job vacancies in Canada have dropped since last summer. And more Canadian businesses were expecting a weaker outlook in Q4 2022, according to the Bank of Canada’s Business Outlook Survey. As a result, concerns about insufficient consumer spending have risen sharply and intentions for investment and hiring have moved lower.

But labour shortages will return as the population continues to age. Those issues are structural rather than cyclical. Having a younger, better educated inflow of immigrant workers could help immensely.

New Canadians don’t fare as well in the jobs market

Immigrants tend to be younger. The share of the “working age” population – or those that are aged between 25 to 64 years old – is 5% higher among immigrants compared to non-immigrants. That should help partially turn back the clock of an aging work force.

New Canadians also tend to be better educated. Over one third have advanced degrees, i.e. a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to just over a fifth for non-immigrants. Immigrants with higher educations are also more likely to have majored in STEM-related fields (science, technology, engineering and math) than their non-immigrant peers.

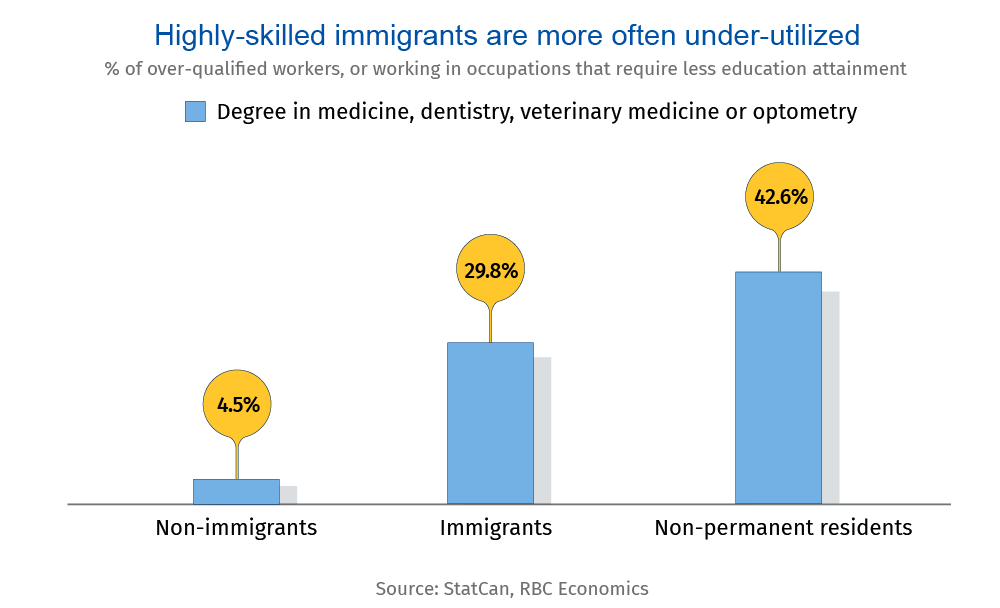

Yet despite being younger and more academically accomplished, immigrants tend to do worse when it comes to finding a suitable job. In other words, more of them tend to work in occupations that require education that’s below their current level.

This challenge, present in all sectors, is particularly daunting for those with degrees in medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine or optometry. By our count, immigrants with a degree in those fields are six times more likely to work in jobs that do not require related training. Their skills are thus “under-utilized” compared to non-immigrants with similar degrees.

That gap however, goes away completely when the location of study is controlled for. Immigrants that trained to be doctors, veterinarians and optometrists within Canada are equally as likely to work in related fields as their non-immigrant peers.

In other words, poor recognition of foreign credentials is the primary obstacle to better utilization of immigrant skills. Moving forward, eliminating those barriers will be critical to ensuring Canada’s success in attracting immigrants continues. Proper integration of their skills could help address worker shortages, add to a more productive labour force and offset increased pressure on inflation and housing.

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group”. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic trends and is responsible for projecting key indicators on GDP, labour markets as well as inflation for both Canada and the US.

Proof Point is edited by Edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More