Proof point: The recent outperformance of the U.S. economy is led by the services sector—a driver that hasn’t materialized in the Canadian economy to the same extent. That makes it less likely that US inflation reacceleration will be replicated in Canada.

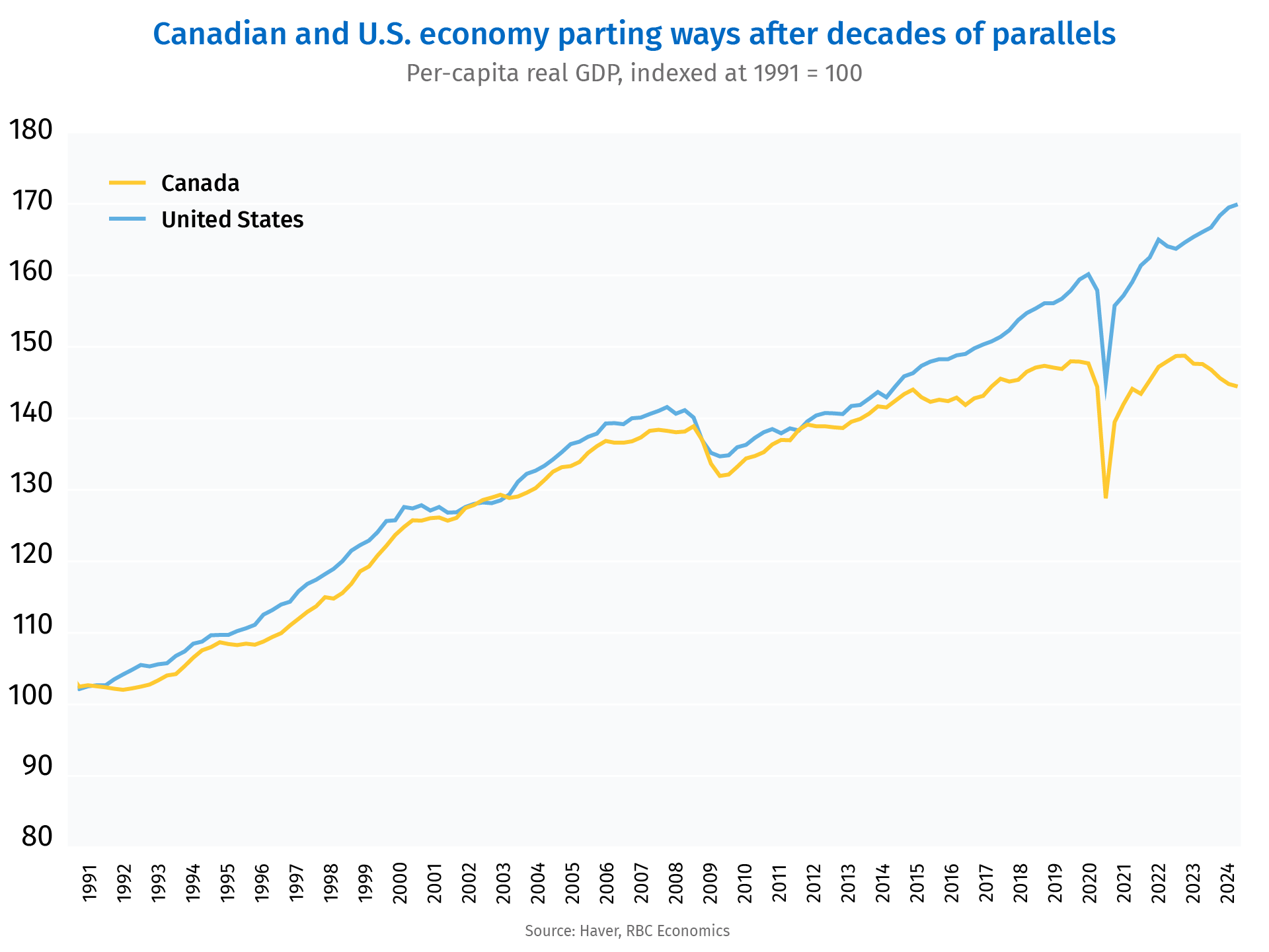

- The underperformance of Canada’s economy versus the U.S. since 2023 is unusual given close cross-border economic ties. By Q1 2024, the gap in gross domestic product growth widened to its largest on record.

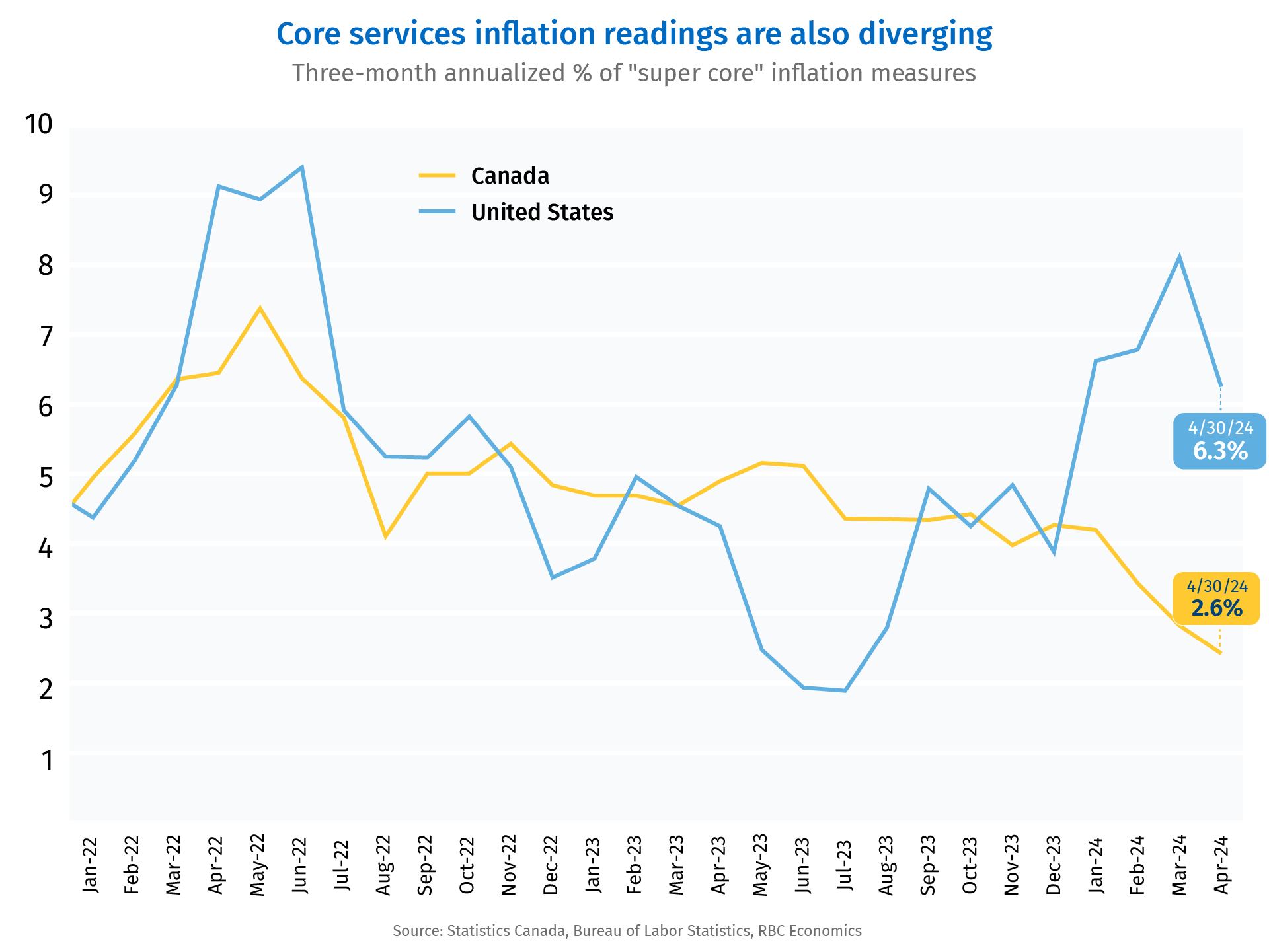

- The divergence is driven by stronger U.S. economic growth led by strength in services and government spending, both of which have smaller cross-border spillover effects. Services inflation has picked up in the U.S. as a result but has continued to moderate in Canada.

- Meanwhile, manufacturing output has stalled in both countries, dragged down by slowing demand for global goods. Goods inflation has been dropping lower globally.

Canada and U.S. diverge after decades of moving in tandem

Canada and the U.S. have one of the closest bilateral economic relationships in the world after decades of collaboration and trade liberalization. The two countries share the world’s longest international land border (close to 9,000 km long). Across that border, $1.3 trillion worth of goods and services were traded in 2023, accounting for two-thirds of Canada’s global trade last year. The two countries also share strong cultural and infrastructure ties and have coordinated closely to meet defence and national security priorities.

Economic performance has generally been in sync between the two countries in the past because of their close relationship, along with inflation trends. But more recently, the Canadian economy has started to severely and persistently underperform. Compared to 2019, Canadian per-capita real GDP as of Q1 this year fell short of the U.S. by 10%—the largest gap since at least 1965. Inflation readings have started to diverge as well. The headline consumer price index in the U.S. has grown at an annualized 4.3% from December to April, compared to just 1.3% in Canada.

In a previous Proof Point, we explained how this economic divergence should warrant different monetary policy responses from the two central banks. But why is Canada’s performance differing from the U.S. now after decades of moving in tandem?

Output gap mainly due to diverging services’ demand

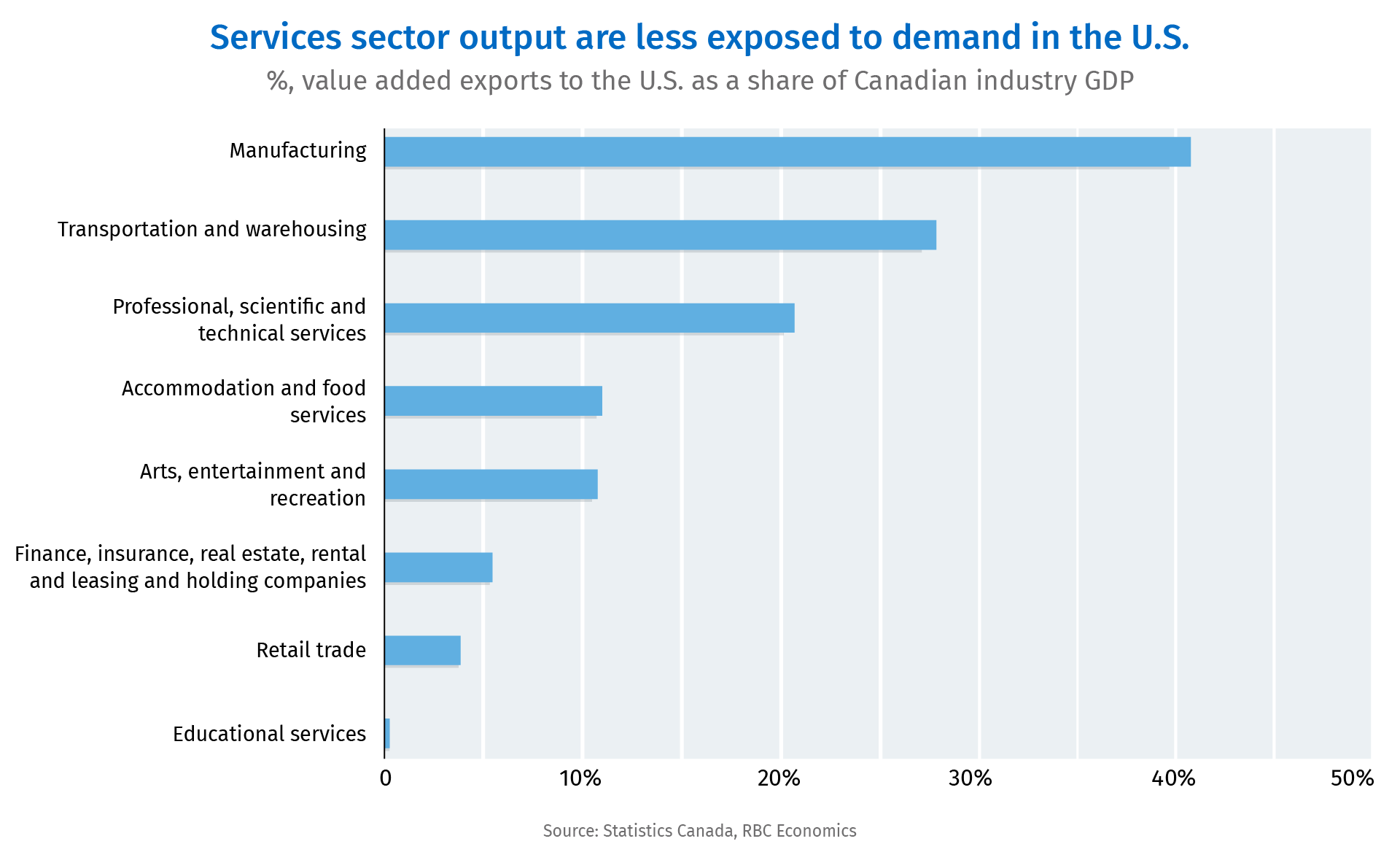

In sectors where trade ties are the strongest, namely manufacturing, conditions are still broadly in sync between Canada and the U.S. In pre-pandemic 2019, over 40% of Canadian manufacturing GDP fulfilled U.S. demand. That means the sector as a whole is very sensitive to softness from abroad. More recently, manufacturing output has stalled in Canada and the U.S. as moderation in global demand for goods (after a buying frenzy during pandemic lockdowns) continues to ripple through supply chains.

But despite slower manufacturing activities, U.S. economic growth has remained broadly resilient. Support has been coming from stronger consumer spending on services and government purchases, which accounted for 70% of GDP growth on average over the last year. However, unlike goods spending, both of those areas are much less likely to import from Canada. In 2019, only 10% of output from Canadian service sectors accounted for demand from the U.S. The share is larger for some service industries like transport and warehousing, but it drops to virtually zero when it comes to healthcare and education.

Ultimately, it’s a divergence in domestic services demand and government spending that’s underpinned the growing gap in output and inflation between Canada and the U.S.

Lagging economy is easing inflation faster in Canada

The silver lining for Canada is that an underperforming economy is also pushing inflation lower than in the U.S., setting the Bank of Canada up to cut interest rates earlier than the U.S. Federal Reserve this year.

The softening global demand for goods has already led to similar soft price growth for tradeable goods in Canada and the U.S. But stronger U.S. service sector demand is feeding through to higher overall inflation pressures. The BoC and the Fed have been focused on “super core” inflation measures that are designed to get a better gauge of price pressures due to domestic services consumption (outside of shelter). This measure has continued to edge lower in Canada in early 2024, but has started to reaccelerate in the U.S.

There is little reason to expect that divergence in service sector price growth will narrow in the near term. The Canadian economy is continuing to underperform even as interest rates are set to drop slowly from high levels. We expect Canadian GDP growth will stay soft this year, rising by just 1.3% as households continue to grapple with elevated borrowing costs. That along with persistent easing of global supply chain constraints should keep Canadian inflation lower, regardless of strong demand out of the U.S.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic analysis and is responsible for projecting key indicators including GDP, employment and inflation for Canada and the US.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More