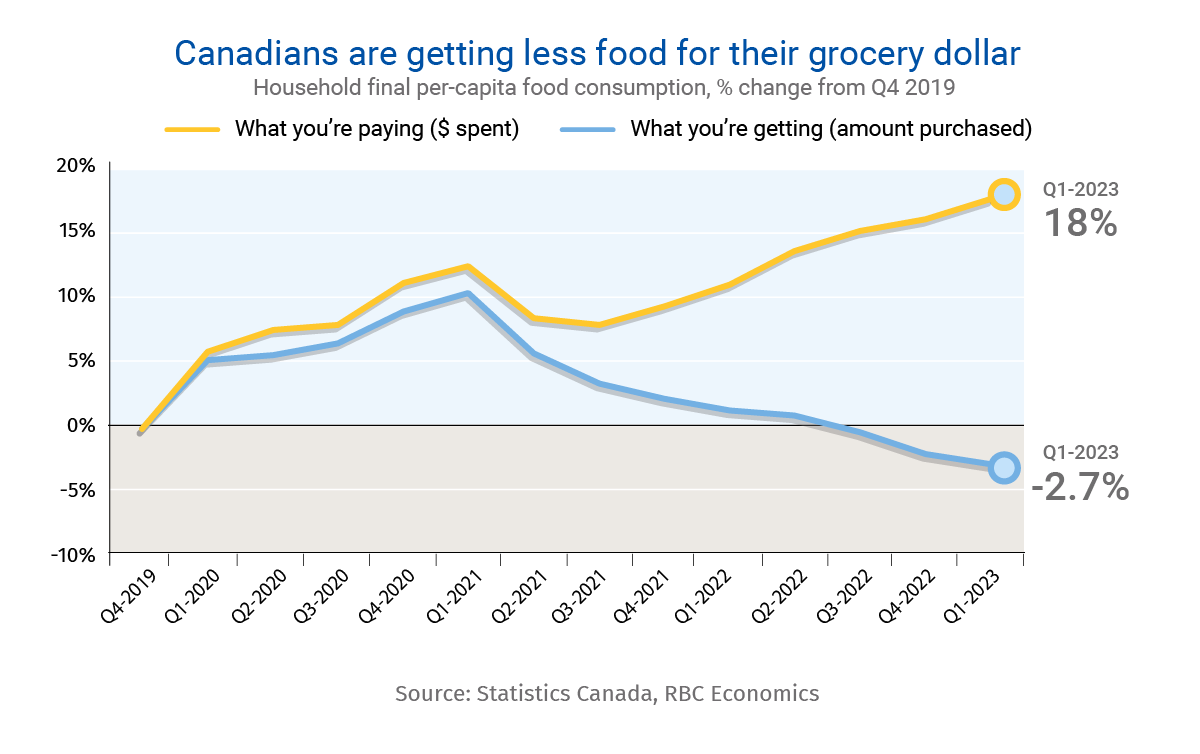

- Food prices have soared by 18% over the past two years, adding to Canadians’ grocery bills at a time when higher rates are already tightening household budgets.

- The supply chain snarls, geopolitical strife and higher input prices behind this rapid price increase have finally moderated.

- And demand will likely slow as Canadians, especially those that earn lower incomes, cut back on pricier groceries due to cost-of-living pressures.

- These factors will put the brakes on the rapid rise in food prices, but they won’t reverse it.

- Bottom line: Food prices won’t rise as rapidly as they did over the last year. But ongoing challenges like extreme weather events and labour shortages suggest a decline from currently elevated levels is unlikely.

Food inflation is a product of many drivers

Prices at the grocery store have remained stubbornly high, driving up the cost of living for all Canadians. The rapid rise that began in 2021 didn’t peak until this January. And as of April, food prices were still 8.3% higher than a year ago.

What drove food prices higher? Pretty much everything.

First, costs for raw food commodities that go into food production (things like wheat, wholesale meat, and oils) soared due to a perfect storm of adverse weather conditions and geopolitical turmoil. The Russian invasion of Ukraine sent wheat prices through the roof and caused a surge in prices for fertilizer and natural gas. And severe drought conditions hit the Prairie provinces, prompting domestic crop production to drop sharply in 2021.

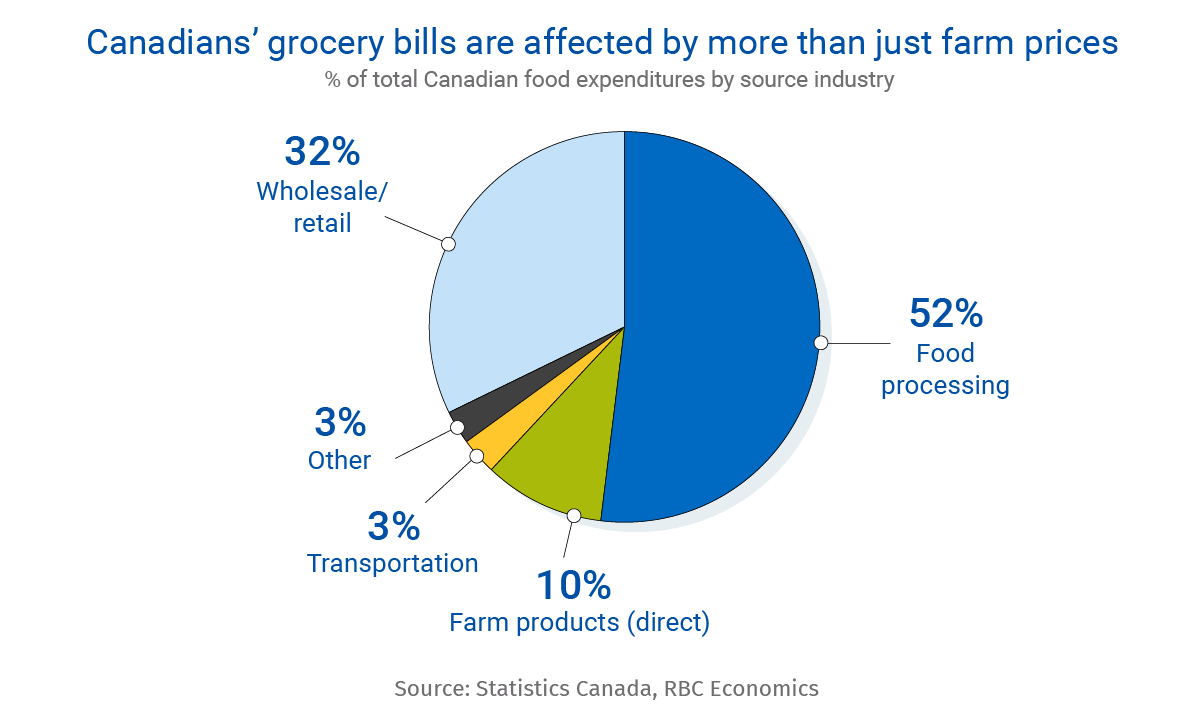

But food prices are driven by a wide range of other costs. Indeed, the cost of raw food commodities accounts for only 10% of the price ultimately paid by consumers. The rest comes from processing, packaging and local transportation, all of which were also pushed up by supply chain disruptions. In normal times, these costs are relatively steady and act as a buffer for those notoriously volatile raw food commodity prices. But last year both sets of costs moved higher, simultaneously. Ocean shipping times and costs surged in 2022, as did the cost of domestic rail and truck transportation. Labour shortages pushed up wage bills across the board. And excess pandemic savings gave consumers higher purchasing power—allowing companies to pass through more of these costs.

Prices are still high and rising, but their momentum is fading

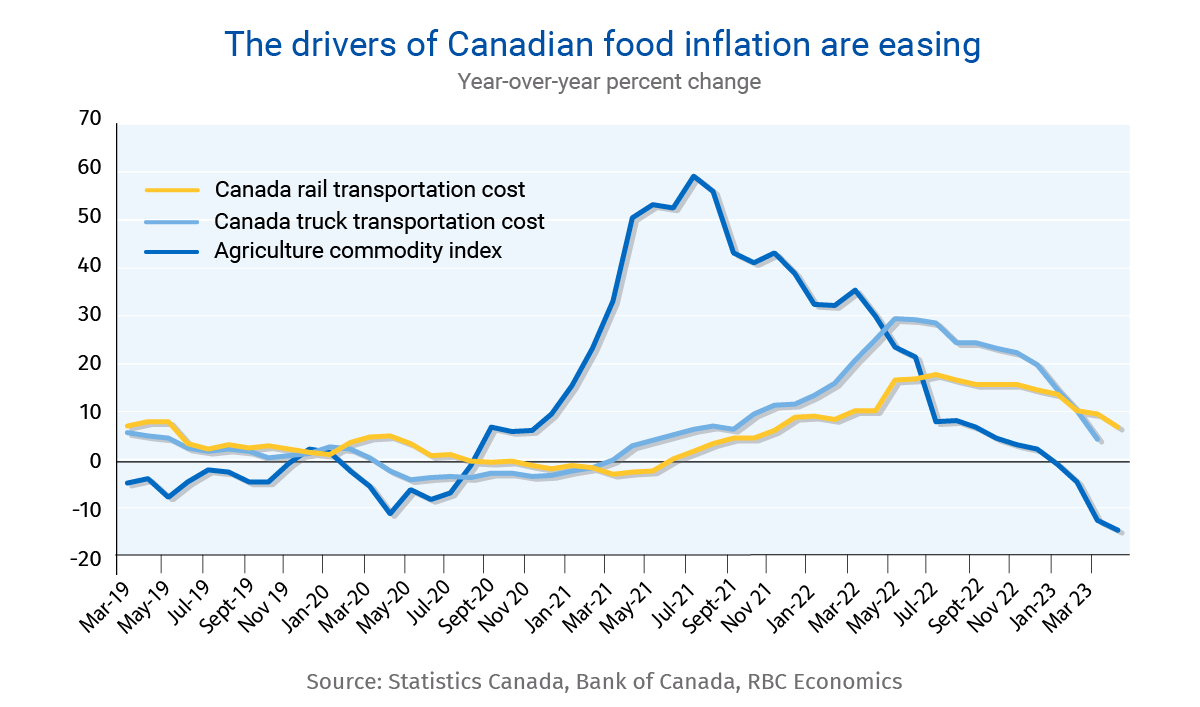

The good news is that almost every one of these factors has moderated. Early 2022 marked a turning point, when constraints tied to global supply chain bottlenecks began to ease. Container shipping times and costs have both normalized back to pre-pandemic levels. And concerns about the impact of geopolitical events on global commodity supply have receded, lowering agriculture and energy commodity prices.

The Farm Product Price Index, which captures prices for agriculture commodities produced and sold in Canada, dropped 3% below year ago levels in March after peaking last summer. The costs for domestic rail and truck transport remain relatively high but look to have changed direction earlier this year as well. The Bank of Canada’s latest Business Outlook Survey flagged even more positive signs when it comes to businesses’ price-setting. More are expecting slower growth and less frequent adjustments to their output prices in the year ahead.

Wage growth in Canada remains elevated amid a tight labour market. The challenge is particularly acute for businesses operating in the accommodation and food services industry, including restaurants and bars where the job vacancy rate (7.6% in March) remains the highest across all sectors. Still, early weaknesses are surfacing, suggesting labour demand has slowed. Job openings have consistently edged lower and employment in Canada outright contracted in May, despite a record increase in population. The easing in labour market tightness should prelude broad-based moderations in wage gains, aiding a continuous easing in food inflation.

Food inflation will slow but structural headwinds will remain

The growth in food prices should continue to slow. Broader inflation pressures and higher debt payments already soaked up virtually all growth in household after-tax income last year and will likely do so again in 2023. Those increased costs are having a larger impact on lower-income households that spend more of their income on non-discretionary food purchases. When higher prices and debt payments dig in individuals tend to either cut back on pricier items or substitute them with cheaper options.

On the surface, it appears each Canadian is spending a record amount on food consumption. But after subtracting out inflation, the “real” value of per capita consumption has been trending lower since early 2021 – meaning Canadians have been paying more for less food. Deteriorating purchasing power should continue to dampen demand before ultimately putting a drag on inflation more broadly, but also on the pace of food price increases.

But several factors suggest prices won’t drop outright. Extreme weather events are becoming more frequent across different regions and could meaningfully limit farm production. This could impact supply chains for other food items, keeping some pressure on overall food inflation. Record low livestock herd sizes reported recently in Canada and the United States is a great example, as it is an aftermath of earlier drought conditions that forced producers to cut back because of pricier feed. And structural labour shortage issues will only be exacerbated by an aging population, squeezing the supply of workers in the decades ahead while supporting wage growth.

All told, while we continue to expect lower food inflation in the current economic cycle, we don’t expect food prices to return to pre-pandemic levels.

Nathan Janzen is the Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic analysis and is responsible for projecting key indicators including GDP, employment and inflation for Canada and the US.

Proof Point is edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More