- High inflation is driving more workers to take labour action to press for wage increases.

- Unfilled workdays due to labour stoppages rose 49% last year compared to the 10-year average that led up to the pandemic.

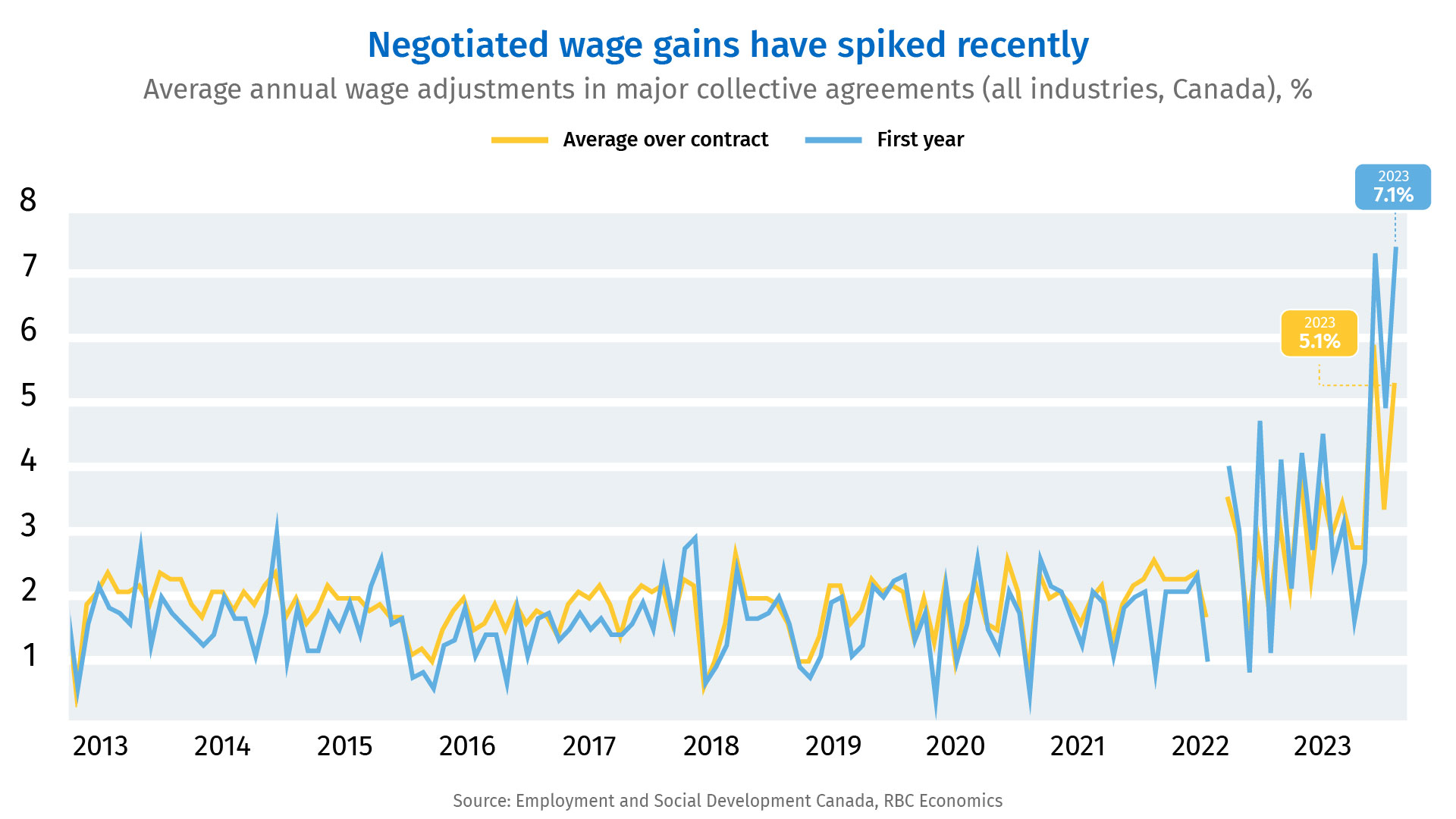

- And first year percentage wage gains in recently negotiated contracts are at the highest level we’ve seen since the early 1990s.

- These jumps could push other workers and their representatives to be more aggressive in their demands, leading to further stoppages.

- The bottom line: As the economy weakens, employers will be less able to meet outsized wage demands. Taming inflation will be key to restoring peace in Canadian labour relations.

Labour relations have become more fractious in Canada

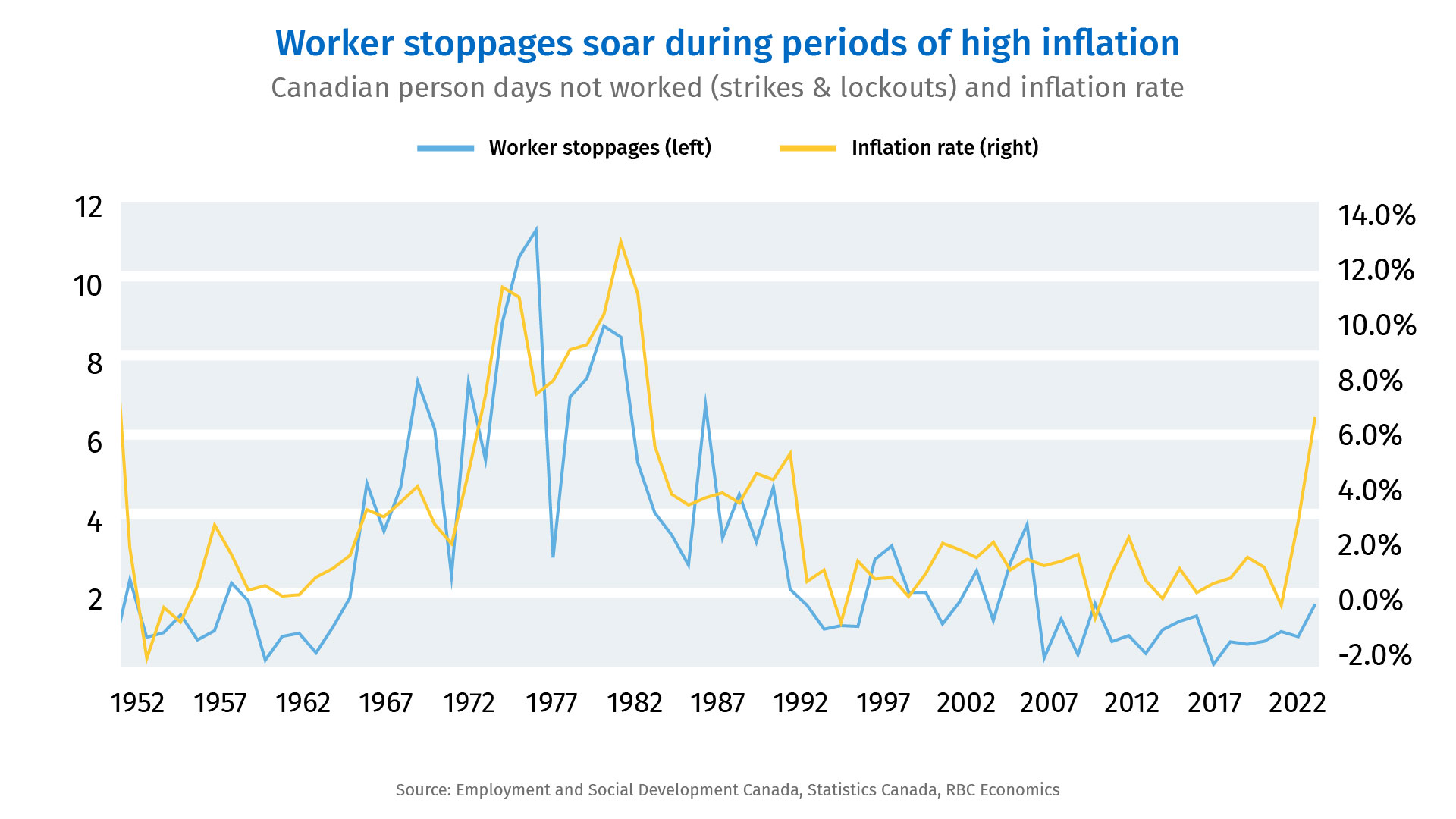

Inflation is elevating the cost of living—and sending labour relations regarding wages into more contentious territory. Lingering around a 40-year high, inflation in Canada has dramatically eroded purchasing power, forcing consumers to rethink their purchases. Across the country, unions have responded by demanding higher pay for their members, increasingly using labour action to further their cause. This growing unrest between employers and staff doesn’t necessarily come as a surprise. Historically, more time is lost to work stoppages during periods of high inflation—as weakening purchasing power prompts workers to rally in labour contract negotiations.

In 2022, there were nearly 160,000 person days not worked due to work stoppages—or 160,000 working days unfulfilled due to a worker strike or lockout. That’s a 49% increase over the 10-year average that led up to the pandemic (2010 – 2019). Though inflation has retreated from last year’s peak, the rise in worker stoppages in 2023 hasn’t shown signs of slowing. In fact, as of July 2023, the number of person days not worked was up 25% from the same period in 2022.

Recently negotiated settlements include decade-high wage gains

Still, recent negotiated wage gains have deviated significantly from historical averages. In fact, in workplaces covered by collective agreements, recent settlements have produced some of the largest gains in decades. First year percentage adjustments were up a stunning 7.1% as of July. That’s just ahead of the 7.0% recorded in 2008—and the highest first-year rate adjustment we’ve seen since the early 1990’s.

Although exceptionally high rates of inflation have no doubt fuelled the resolve of workers, there are likely other forces contributing to the outcomes of recent wage negotiations. Indeed, Canada’s aging population has accelerated acute labour shortages, putting more bargaining power in the hands of employees. At the same time, the country’s unionization rate has ticked higher— granting a greater share of the Canadian workforce protection under collective agreements. This is likely due to the growing share of employees working in industries or classes where union coverage is highest (i.e. education, healthcare, public admin), rather than a resurgence in unions. Nonetheless, the jump in recent wage settlements could entice other workers and their representatives to be more aggressive with their demands—especially when workers can soak up a lot of wage increases before catching up to inflation.

Taming inflation is key to curbing work stoppages

As the economy weakens, the ability of employers to acquiesce to firmer demands will diminish. And passing on higher operating costs (including wages) to customers will get harder. These conflicting goals between negotiating parties risk more impasses and labour disputes in the year ahead.

On the heels of the strike by 155,000 Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) workers, port strikes across B.C., and the Metro food retailer strike in Ontario, more turmoil in labour relations raises the risk of keeping the Canadian economy in extended ‘transitory’ turbulence. As more labour contracts expire this year, taming inflation and bringing balance back to the country’s labour market will be key to restoring peace to labour relations in Canada.

Robert Hogue is responsible for providing analysis and forecasts on the Canadian housing market and provincial economies. Robert holds a Master’s degree in economics from Queen’s University and a Bachelor’s degree from Université de Montréal. He joined RBC in 2008.

Rachel Battaglia is an economist at RBC. She is a member of the Macro and Regional Analysis Group, providing analysis for the provincial macroeconomic outlook.

Proof Point is edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More