- Wages are growing fast in Canada—but not fast enough to match inflation.

- And wage increases will likely be soaked up by higher prices and debt costs in 2023, lowering disposable incomes.

- Households are expected to cut back on spending to adjust, prompting inflation—already losing steam—to fall further.

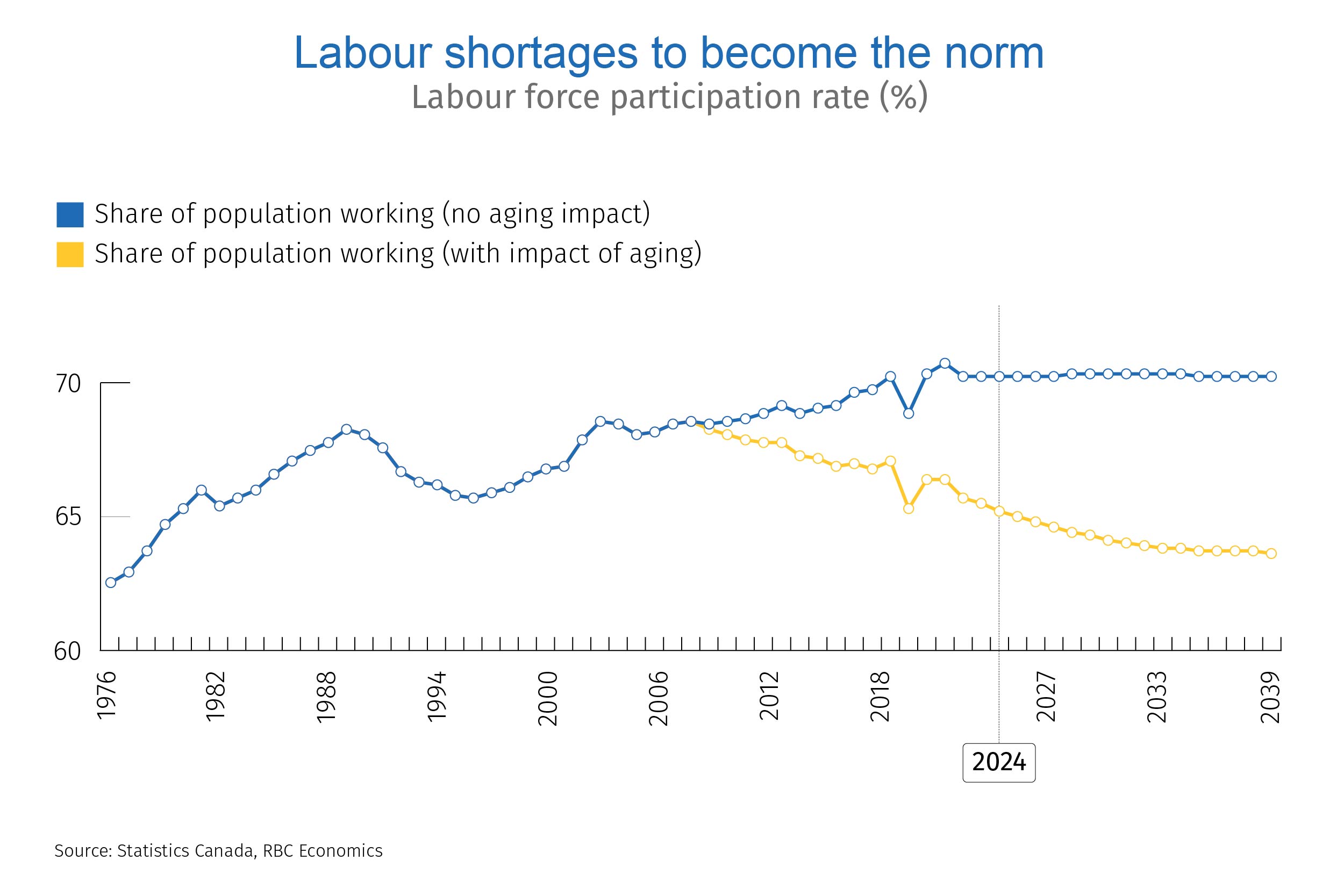

- But over the long run, an aging workforce threatens to make labour shortages a “new normal”. This will ensure workers retain power to negotiate higher wages.

- The bottom line: Higher wages due to long-run structural labour shortages could reignite spending, and inflation. Without greater business investment, higher interest rates could be needed to offset this force.

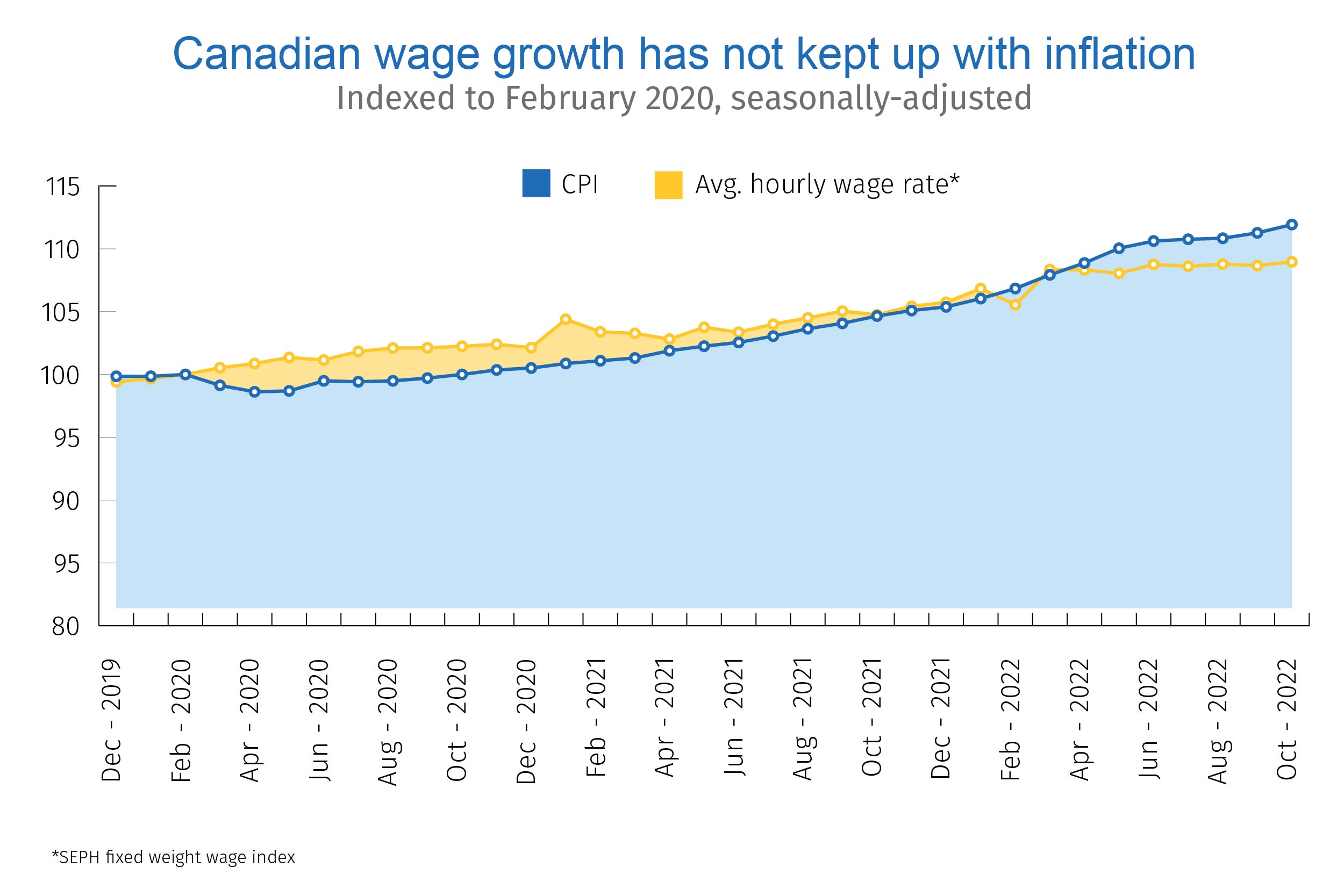

Wage growth is still lagging inflation

Accelerating wage growth and historic worker shortages characterized the labour market for much of 2022. As of November, average hourly earnings rose ~10% compared to pre-pandemic levels—the fastest pace over a time period of that length since the 1990s.

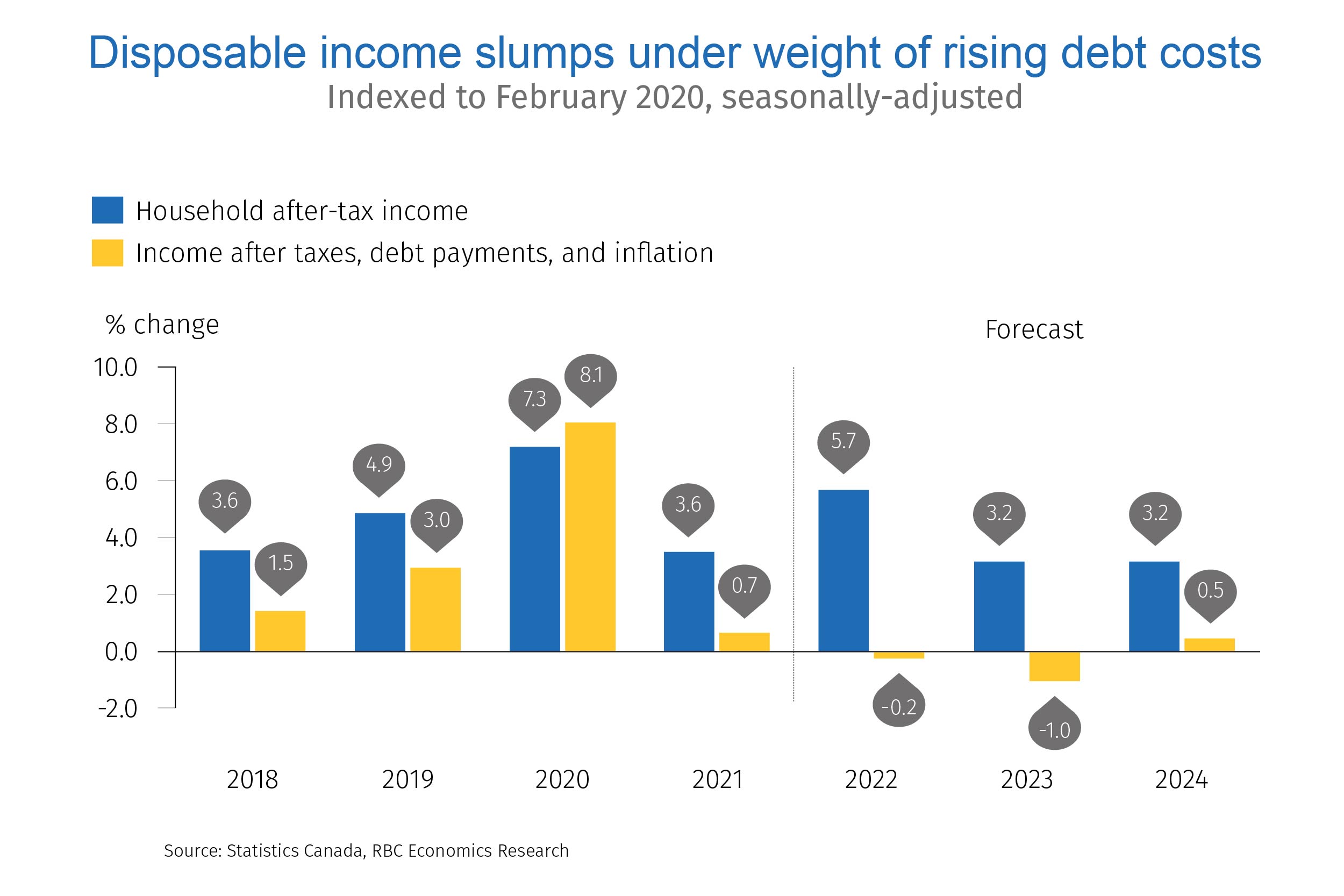

But that still wasn’t enough to catch inflation, which soared 12% above where it was before the crisis. And as workers grappled with higher prices, they were also saddled with an almost 20% jump in debt servicing costs as the Bank of Canada aggressively raised interest rates. By our count, household income after taxes, debt payments, and inflation was 0.2% lower in 2022. We expect an even larger 1% drop in 2023 as Bank of Canada interest rate hikes (adding to 425 basis points over the last year) continue to flow through to debt servicing costs.

Searing wage growth will cool with inflation in the year ahead

The concern now is that strong wage growth will persist to the point that it becomes counter-productive— that is, where it begins to push the price of goods and services above actual purchasing power. Should soaring wages fuel greater spending, they could at best slow the pace at which inflation eases and at worst, reignite it.

What could temper wage growth? Currently, an acute shortage of workers is powering it higher. There are still nearly 50% more job openings compared to pre-pandemic levels. And the employers posting those jobs are trying to fill them from a pool of unemployed workers that’s 11% smaller than it was before the crisis. To compete for staff, employers are boosting pay levels.

But countering this trend are those BoC interest rate hikes—which have yet to make their full impact on household debt servicing costs. Workers shouldering these heavier debt burdens are spending less, pinching demand. And while the number of job openings remains very high, growth in these postings is slowing down. In particular, postings in the manufacturing sector have softened significantly in recent months.

With real household purchasing power expected to fall for a second consecutive year in 2023, so too will spending. This gradual cooling of a once red-hot economy is expected to ease both inflation and wage pressures.

Long run labour shortages could see inflation strike back

While higher wage growth has not proven to be immediately inflationary, that story could change over time. As we move beyond the next recession, labour shortages will not go away. More Baby Boomers will retire, and with fewer Gen Zs to replace them, higher job vacancy rates (above the pre-pandemic average) and lower unemployment rates could become the new normal. With a dearth of available workers, prospective employees will have more muscle at the bargaining table, which will in turn fuel more rapid wage growth.

Longer-run structural labour shortages can lead to potentially stronger inflation pressures (i.e. spending). This in turn, can require central banks to lift interest rates. Increased business productivity, through capital investments, can offset those pressures by boosting revenues and making it easier for businesses to afford higher wage bills. Indeed, higher wage costs can be an incentive for businesses to spend more on productivity-enhancing investments like automation.

But in the absence of this productivity improvement, demand will exceed the available supply of goods and services, adding new inflationary pressure. That could force central banks to keep interest rates above pre-pandemic levels for longer to offset higher prices.

Nathan Janzen is an Assistant Chief Economist, leading the macroeconomic analysis group. His focus is on analysis and forecasting macroeconomic developments in Canada and the United States.

Carrie Freestone is a member of the macroeconomic analysis group and is responsible for examining key economic trends including consumer spending, labour markets, GDP, and inflation.

Proof Point is edited by Edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More