The New Climate Bargain is the latest report in RBC Economics and Thought Leadership’s climate series, building from the team’s flagship report, The $2 Trillion Transition, which was launched in October 2021. This climate series is designed to inform and inspire Canadian prosperity, while advancing RBC’s ongoing commitment to speak up for smart climate solutions, a key pillar of RBC’s Climate Blueprint.

Climate change, meet energy security

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a cataclysmic moment for global energy markets. As governments and consumers grapple with energy shortages and high gas and power bills, climate change policies are being thrust into competition with energy security.

The old energy order is giving way to a new, disorderly one as Europe and Asia seek alternate supplies to replace Russian exports. Moscow’s ploy to exploit Europe’s energy vulnerability will not be forgotten in a hurry, and has accelerated two contradictory responses: rapid decarbonization and a scramble to raise fossil fuel production at least in the short term.

The dichotomy underscores a hard truth: short of major additional action, oil and gas will likely remain critical and contentious energy sources for longer than some think.

This poses some critical questions for the West:

Should Canada and the U.S. raise production significantly in the short term to cool prices?

How does higher output square with their ambitious emissions reduction plans?

If governments fail to balance climate action and energy security, will high energy costs and emissions erode public trust?

Our research shows both goals are within reach—but at significant cost. Canada can still reach its 2050 Net Zero targets, but it may not be a linear journey. There isn’t a moment to lose. Policy action over the next 24 months must chart Canada’s climate-and-energy path to Net Zero by 2050.

Key findings

Canada’s oil and gas sector can support near-term energy security while advancing climate action, but will need regulatory certainty and support at all levels of government.

Oil sands and conventional producers could raise production by up to 500,000 barrels per day from 2021 levels.

This could add 9 million tonnes of greenhouse gases per year, costing at least $1.5 billion annually to abate—but bringing potential net benefits of $10.5 billion annually. Critically, if Canadian barrels displace those of other producers, there would be no additional global emissions.

Meeting climate targets despite new production will demand significant investment in methane reductions, as well as electrification and carbon capture across industries.

Cutting emissions 40% from current levels in the oil sands by 2030 will likely require $45 billion to $65 billion in capital spending between 2024 and 2030, peaking at about $9 billion per year mid-decade.

Full upstream decarbonization with carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS), a critical emissions-reduction technology, will require oil prices averaging roughly US$50 WTI through 2050.

A deliberate approach to deploying decarbonization technology in the oil sands is needed to avoid over-investing in costly solutions. CCUS should be viewed as just one tool at Canada’s disposal.

CHAPTER 1

Oil is here for the long haul

The journey to decarbonization was never going to be smooth. But it’s turning out to be a highly disruptive economic and political event.

While energy security and climate change have long been on a collision course, Moscow’s aggression has brought the conflict to a head. Early indications suggest at least 3 million barrels per day of Russian oil could be shut in as buyers stay on the sidelines. In the longer term, a bigger portion of Russia’s 11.7 million bpd production could be challenged in the face of oil majors’ exits and as Moscow becomes an international pariah.

The Russian invasion has prompted calls to cut oil and gas demand by accelerating investments in clean energy technologies, a move that could blunt bad actors’ ability to hold energy markets hostage. But most countries would struggle to switch their energy sources rapidly over the next decade.

For example, zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) accounted for just 5.6% of Canadian light vehicle registrations in 20211. Given this modest starting point, it would take a Herculean effort to reach the ZEV mandates set out in Ottawa’s recently announced Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP). The mandate requires at least 60% of all new light-duty vehicle sales be ZEVs in 2030. Even if Canada meets that ambitious target, 84% of light vehicles will still run on gasoline by the end of the decade

Russia’s actions in Ukraine have shocked energy markets but it’s still too early to know if the world will double-down on investments in renewable energy or lean on fossil fuels to manage the shortages. Most likely, both will see a wave of new investment.

Early estimates suggest global oil and gas capital expenditures will increase 11.6% year-on-year to US$533 billion in 2022. They’ll rise another 4% in 2023, before returning to pre-pandemic levels in 2024, according to Fitch Solutions.

And the world may be falling back into old consumption patterns. Germany plans to build LNG terminals even as it accelerates investments in renewables, while the IEA has recommended a temporary switch to coal and oil-fired electricity to wean the European Union off Russian gas. Both would add to, rather than cut, emissions.

The hurried response is aimed at protecting consumers from price spikes. Persistently high energy prices are cascading across energy-intensive industries, raising prices of staple commodities and denting the budgets of vulnerable households and small businesses. In such an environment, energy accessibility and affordability usually trump climate considerations for consumers.

There are already signs that government resolve is weakening: Germany, California, and British Columbia, usually climate leaders, are offering subsidies to offset high gasoline and power prices.

So far, high fossil fuel prices have done little to curtail demand, at least in North America. Consumers have room to absorb higher prices, since US gasoline costs are still nearly a full percentage point lower as a share of personal consumption expenditures than early in the 2000s, and Canadians have amassed major savings stockpiles during the pandemic.

While there is regulatory and investor pressure on energy suppliers to rein in direct emissions (Scope 1) and indirect emissions from purchased electricity (Scope 2), governments have tiptoed around the equally significant challenge of altering consumer behaviour.

Globally, explicit and implicit fossil-fuel subsidies primarily focused on the consumer stood at US$5.9 trillion in 2020, or about 6.8% of GDP. And they’re expected to rise to 7.4% of GDP by 2025, according to the International Monetary Fund. Consumer behaviour trends also suggest preference continues to take precedence over climate considerations: sales of SUVs soared 10% and accounted for 45% of all car sales last year, adding 120 million tonnes of CO2 annually.

Taken together, these indicators suggest oil demand will rise rather than fall in this decade. The IEA’s short-term forecast pegs demand for oil at 104 million barrels per day in 2026, compared to around 99.7 million this year. Production growth over the next few years will be led by the United States, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Iraq and Brazil.

Surging global energy demand

Energy demand over the past four decades has grown around 1.75% annually.

With global population set to rise by another 2 billion people by 2050, expect that demand to surge again. As a base case, the IEA projects energy demand will grow 1% annually over the next three decades.

While renewable energy consumption is forecast to lead growth with a 3.2% annual increase between 2020 and 2050, oil demand is expected to rise by 0.5% and natural gas by 1.3% annually. Absent greater action, rising investment in clean energy doesn’t necessarily mean a decline in traditional energy sources.

Still, a bullish scenario for oil markets is far from certain. The IEA’s less optimistic scenario pencils in a 25% decline in oil demand, with prices averaging US$64 per barrel. However, if a greater push emerges to get to Net Zero, prices drop as low as US$24. Net Zero production will be a prerequisite to sell into that shrinking oil market.

The trouble is, this base case for fossil fuel demand is at odds with climate goals.

Compared to 1.5°, 2° could be even more destructive for the planet, with twice as many plants and animals seeing their habitats diminish, large swathes of sea coral becoming extinct, and millions more people facing heatwaves, floods, and water scarcity3.

Against that bleak backdrop, Western oil production should not continue unrestricted no matter how acute the energy security imperatives. To resolve that tension, new Western production must displace other sources, to stabilize global emissions (including Scope 3 emissions that include an organization’s upstream and downstream emissions), and policymakers must redouble efforts to drive down oil demand.

Canada has the tools and technologies needed to rapidly deploy renewable power, electrify buildings and transport infrastructure, and, in some cases, industry. But managing the impact of intermittent renewables and the high cost of some alternatives will require careful planning, too.

But displacing development of fossil fuel resources elsewhere will be more challenging. Western economies need to be on the same page, targeting a growing Western share of oil production and falling overall oil demand. And they’ll need to agree to pay a premium for oil from climate-compliant producers.

Canada and the U.S. should pursue a North America energy security alliance that secures both conventional energy, and the underlying resources for energy transition. Elements of such a strategy include long-term contracts with U.S. refineries that provide certainty for Canadian oil producers to invest in decarbonization, maintenance of existing pipelines and support for power transmission lines.

Canada must ensure it receives consideration for its stability and energy decarbonization efforts. Long-term contracts could seek to put a floor on oil prices at levels that support decarbonization investments in Canada, and reduce the impact of extremely high oil prices for US consumers.

CHAPTER 2

Canada’s role in ensuring energy security

Energy is a critical sector for Canada. Oil and gas extraction and support activities, refining, distribution and transportation, could account for close to 10% of Canadian GDP in 2022. In addition to directly employing 178,500 Canadians, the industry supported 415,000 indirect jobs in 2020.

Resource-rich provincial governments benefit from royalties, which are expected to total at least $18 billion in 2022, up 50% from 2021 due to high energy prices and fully paid-down projects. 4

Given its sizeable resources, Canada can play a critical role in ensuring global energy security—that both addresses short-term energy shortages and burnishes Canada’s status as a soft power whose resource wealth can neutralize non-democratic forces. The challenge is to do so without threatening our climate goals.

First, the good news. Canada can boost oil and gas exports to the U.S., which, in turn will raise the U.S.’s ability to expand energy supplies to the rest of the world.

We estimate that Canada can raise production by as much as 500,000 barrels per day through a combination of oil sands and conventional oil production to overcome supply deficits over the next year.

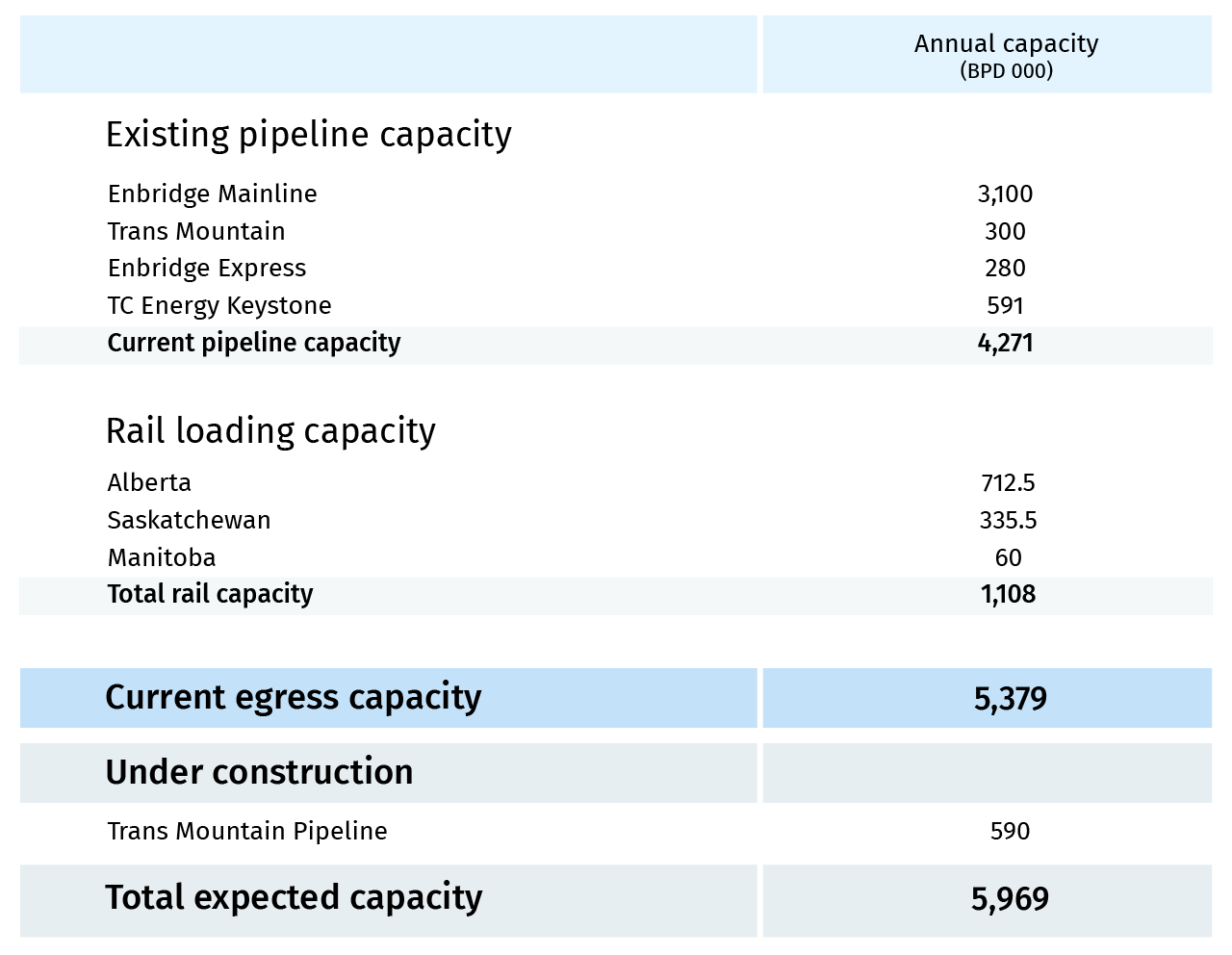

While Canada’s exports are already at near record levels with an average of 3.76 million bpd in 2021, U.S.-destined pipeline capacity stands at more than 4 million bpd.

Over the past few years, Canadian pipeline operators have invested in decongesting their systems to optimize capacity, but further notable increases may require new lines, according to industry.

But under a realistic production forecast, that may not be necessary. The Canada Energy Regulator’s latest forecast of 5.3 million bpd of pipeline and rail capacity by 2050 should be sufficient to handle Canadian production.

Around 1 million bpd of total rail loading capacity suggests that, in a pinch, current oil export capacity can support near-term expansion. However, railway companies will be challenged to supply specialized rail cars and juggle demand from agriculture, food and minerals producers already struggling with supply chain challenges in order to accommodate higher oil shipments.

Canadian takeaway capacity is sufficient

Source: Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, Canada Energy Regulator

The bad news: rising production could challenge Canada’s recently-announced ERP target to cut oil and gas sector emissions by 42% as new production adds as many as 9 million tonnes of additional emissions.

Laying the Foundation for Emissions Cuts

Required under Canada’s Net Zero legislation, the Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) and the subsequent federal budget marked a tone-shift for climate policy. The document outlined emissions targets at the sectoral level, and provided significant new funding for transportation, carbon capture, and nature-based climate solutions.

But when it comes to the all-important energy sector, it was short on details. Mindful of a war in Ukraine and a full-blown global energy crisis that is still unfolding, the ERP underscored the dilemma of setting aspirational climate goals at a time of structural disruption in energy markets.

The ERP assumes rising Canadian oil production. But recent announcements pay more attention to new projects’ emissions rather than their economic benefits. The message from Ottawa is, increasingly, that only the lowest-carbon operations will be given social license to produce.

It will be a challenge, but we believe Canada can accelerate oil production and achieve its stated goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40 to 45% by the end of the decade.

There are no guarantees. The industry may not respond to the call to raise production without resetting emissions targets and obtaining social licence. Investors have prioritized dividends and buybacks over ploughing back profits to generate more barrels, while labour shortages and stringent ESG targets are further discouraging a push to raise production.

Should oil prices rise further, that may not be the case. But to secure more energy supplies, Canadian policymakers should signal greater comfort with a short-term rise in oil emissions—as long as emissions start to fall in other areas, or oil production starts coming offline beyond 2030.

At the same time, policy makers can pull other levers to ensure we remain close to our 2030 emissions targets. Rising oil sector emissions can be offset with cuts elsewhere, such as by accelerating renewable power infrastructure and building decarbonization, and improving energy efficiency. The economic benefit of rising oil production can help offset the cost of accelerating other sectors’ decarbonization, especially buildings and electricity, where supply chain bottlenecks may be less severe than transportation.

Overall, there’s no need for near-term energy security challenges to threaten the world’s commitment to Net Zero. But cross-sector trade-offs won’t work in the long term. Canadian oil producers will need to cut not just industry-average emissions, but overall emissions in each type of production. Making the long term investments needed to do so requires clarity, and there’s no better clarifying moment than an energy crisis.

CHAPTER 3

The need for CCUS

While supporting near-term energy security and meeting future climate targets will be challenging, our report $2 Trillion Transition: Canada’s Road to Net Zero found that technologies to achieve deep cuts are readily available for transportation, buildings and electricity.

The ERP already targets 42% emissions cuts in the oil and gas sector, nearly 40% of which come from the oil sands, where cuts are costly and technically difficult. This will be challenging to achieve, given the industry’s reliance on capital-intensive carbon capture projects for deep cuts.

Development of the recently-approved Bay du Nord oil field off the coast of Newfoundland, which may only start producing oil in the late-2020s, could add some 4.5 million tonnes over the life of the project.

But conventional oil and natural gas producers appear well placed to cut emissions over the next decade. For one, their emissions are lower per barrel, due to lower energy input. For another, about 40% of upstream natural gas emissions, and two-thirds of conventional oil emissions come from methane releases and leaks. These are slated for a 75% reduction by 2030 via widespread leak detection and vapour recovery units, making up nearly the entire contribution of cuts in the ERP.

More effort to electrify facilities near B.C.’s clean electricity grid to address combustion could deepen cuts and make room within the sector for rising production. In the medium term, with greater effort by utilities to bring electricity to more parts of B.C. and Alberta’s oil and gas fields, deeper decarbonization is possible.

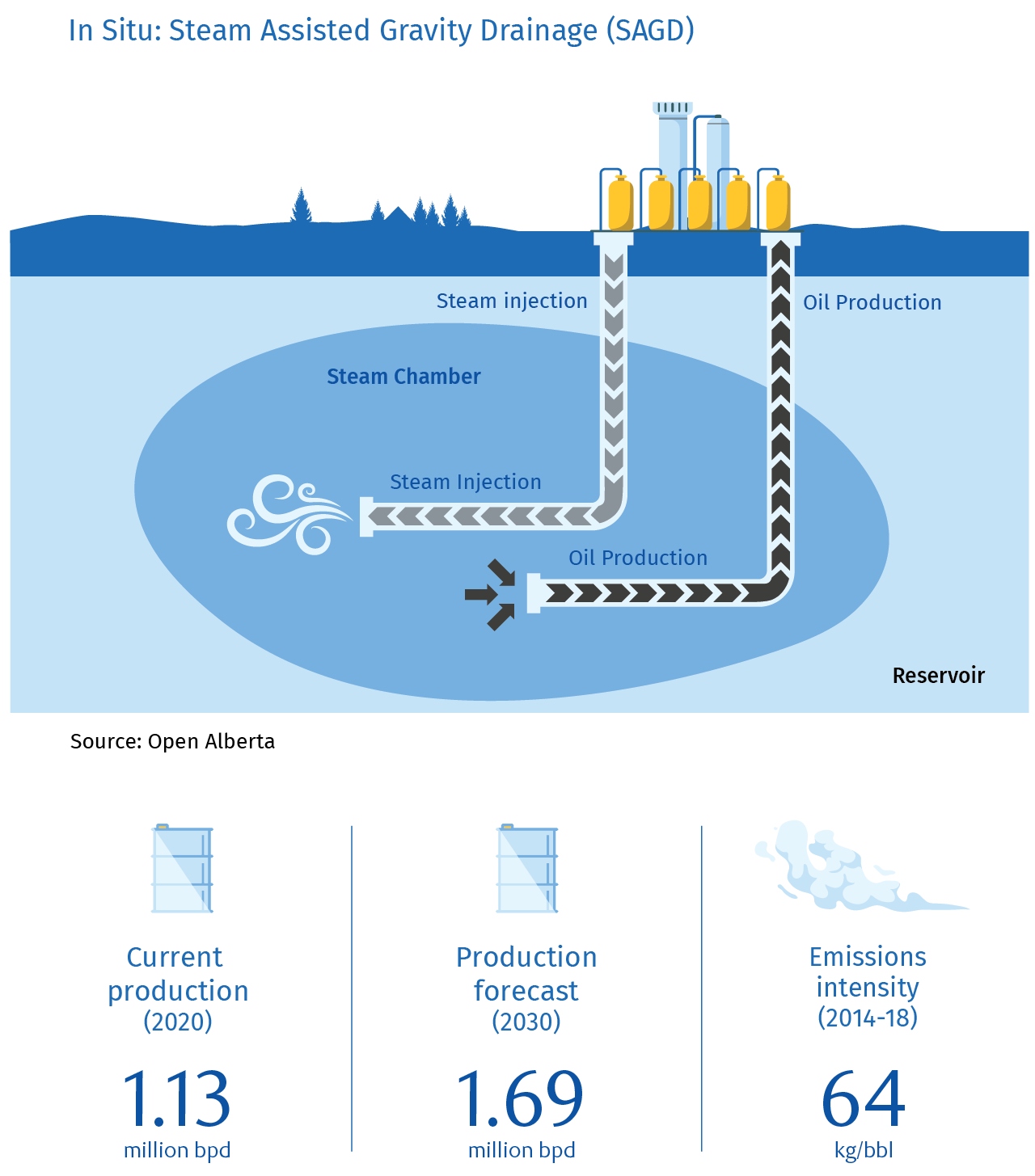

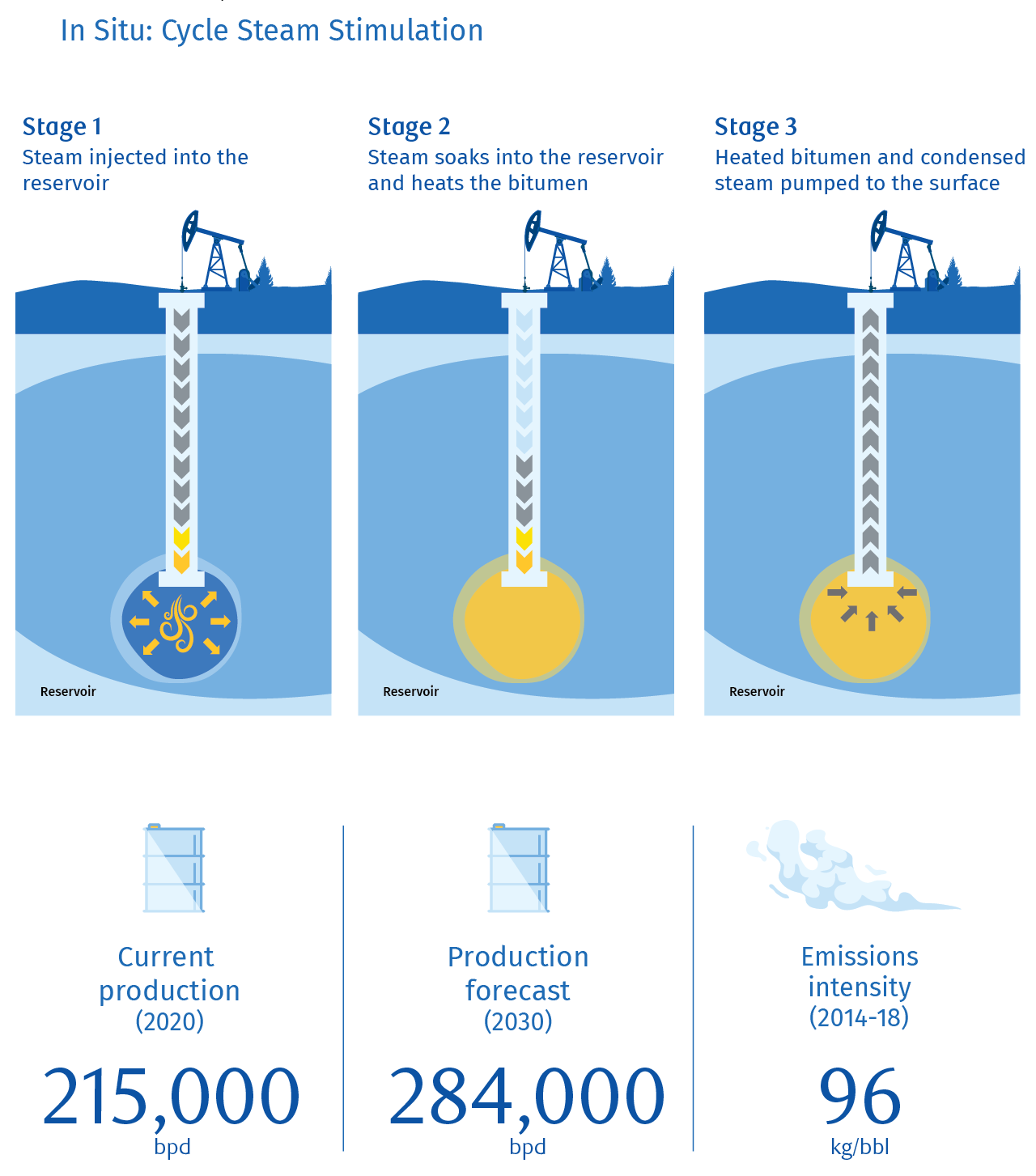

Types of bitumen production

Mining: Shovel-Ready

Only a fifth of the oil sands deposit can be extracted by mining. Massive shovels scoop out the bitumen and ship it on large trucks to cleaning facilities where it is separated from sand, water and clay, or tailings. The waste material is sent to tailings ponds.

Current production (2020): 1.49 million bpd

Production forecast (2030): 1.70 million bpd

The separated oil is processed in two ways:

Synthetic Crude Oil

Synthetic crude oil (SCO): Once stripped of the waste, the bitumen is converted to a sweet, synthetic crude oil (SCO), in upgraders, or complex heavy oil refineries. While the process adds to the oil’s emissions at the upstream stage, the lighter, sulphur-free end product can be sold to a conventional refinery.

Average emissions intensity (2014-18): 95 kg/bbl

Froth treatment

Mined dilbit or paraffinic froth treatment (PFT): Two new oil sands projects, Imperial Oil’s Kearl Oil Sands Project and Suncor Energy-led Fort Hills, use the PFT method. The process removes the bitumen’s heaviest components and is diluted with lighter blends to produce dilbit. PFT uses a paraffinic solvent as diluent, producing a clean end product that can be transported without the need to upgrade, thereby reducing upstream emissions.

Average emissions intensity (2014-18): 46 kg CO2/bbl

If Canada is serious about cutting oil sands emissions by 2030, the first move is to bring down emissions intensity—the CO2 emitted per barrel—with production efficiencies. But this isn’t likely to bring emissions on track to meet our climate goals.

Without new facilities dragging down average carbon emissions5, oil sands emissions per barrel could improve about 6 to 7% by 2030. Some of these improvements would come at high costs6. Others are only economical for new facilities, or those not yet past the prototype stage.

Over the long term, breakthrough technologies that provide low- or no-carbon steam, like hydrogen boilers and small modular nuclear reactors, could revolutionize oil sands production, as both provide zero-carbon sources of heat and power. Unlike conventional producers, who consistently need to drill new wells, and move emissions-controlling equipment each time, the stationary nature and slow decline rate of oil sands may improve the economics of costlier equipment like reactors.

Until then, carbon capture is the key technology for cutting emissions deeply. The IEA and UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have both identified CCUS as a technology that can help cut emissions with conducive policies, public support and innovation.

What’s more: CCUS projects don’t inherently have financial returns. The product they make, CO2, has minimal market value, so returns need to be engineered from government policy, like carbon pricing or fuel standards. And in many cases, the avoided taxes or regulatory payments are highly uncertain.

Accordingly, most CCUS projects to date, in Canada and elsewhere, have been heavily subsidized by tax credits or government investments. Or have required corporations to voluntarily pay very high carbon prices. To justify government investment, we need to be sure oil sands production at scale is competitive in the long run.

To justify government investment, we need to be sure oil sands production at scale is competitive in the long run.

Emissions Catchers: Carbon Capture Utilization & Storage Projects in Canada

CCUS projects in operation, under construction and proposed

CHAPTER 4

Can Net Zero oil sands compete in global markets?

The Oil Sands Pathways Initiative, an industry group aimed at getting the oil sands to Net Zero, is targeting targeting 22 million tonnes (Mt) in emissions cuts by 2030. To accelerate investment in CCUS, the recent federal budget announced a refundable investment tax credit totaling a little less than 50% of project costs to 2030. This is a significant step in the right direction, and should help spur studies of, and investment in, the best CCUS sites.7

But for widespread deployment—government modelling implies some 15 to 18 Mt of installed capacity by 2030—more effort from provinces will be needed. This could include a top-up on the credit, but also improvements to non-financial parts of CCUS projects like permitting, liability, and storage rights. The government’s commitment to explore carbon pricing certainty could also help de-risk cash flows from CCUS projects.

Doing so would require between $45 and $65 billion in total capital spending between 2024 and 2030, totaling $9 billion per year at its peak. This would be a significant draw relative to the industry’s current investment levels. Assuming the government continues to absorb half the bill, total taxpayer costs would be significant, too.

While previous rounds of high oil prices have led to investment booms, the short-term landscape has changed. After a turbulent few years, oil sector investors prefer to see firms focus on dividends and share buybacks rather than invest in expensive carbon capture projects.

The long-term outlook also challenges major investments in oil sands projects, especially as most forecasts have oil demand falling in the coming decades, as drivers switch to electric vehicles. A major push for decarbonization to reduce demand for Russian oil and gas in Europe may accelerate this trend.

In that context, Canada’s challenge rests in removing carbon emissions from the oil sands without making them uneconomical to extract.

We estimate full decarbonization of the oil sands8 could cost between $6 and $14 per barrel for mined bitumen and $17 and $23 for in situ bitumen. Overall, WTI would have to average about US$50 over the life of the project to meet investor expectations. While that has largely been the case since 2005, uncertain future demand means that may be a high bar.

That said, oil sands wells decline more slowly than conventional ones, making them more suitable for site-specific and immobile CCUS. If CCUS remains a key technology for decarbonizing oil, that may be a structural advantage for oil sands producers. Ignoring sunk capital costs, steam assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) facilities with CCUS could run profitably at prices as low as US$40.

These relatively high abatement costs mean Canadian producers should take a pragmatic approach to CCUS. Deploying investments gradually through the 2020s and 2030s would allow for cost efficiencies and leave room for future technologies to potentially lower costs. A slower approach is at loggerheads with deep emissions cuts this decade, but a measured, realistic approach to decarbonizing heavy oil production will be critical to maintain Canada’s economic competitiveness in the sector.

In the long term, given a majority of emissions from oil consumption come from burning the fuel, industry will need to invest in developing uses for bitumen that don’t require combustion. IEA forecasts put non-combustion demand near 15 million barrels per day in 2050, for things such as lubricants, waxes and asphalt. Opportunities to take the heaviest parts of Canadian barrels and make value-added products like carbon fibre are in the early stages of innovation, but could be a key for diversification and transition in the oil sands.

Of course, this may yet be challenged by emissions reduction mandates levied by government and the significant uncertainty around future oil and carbon prices. We’ll need a coordinated effort by industry and government to address these challenges.

CHAPTER 5

Managing volatility in the investment cycle

The oil sector is highly cyclical, which makes long term investments difficult especially when coupled with the uncertainty of returns for decarbonization projects. For one, it’s likely oil production and emissions will fluctuate through 2050 as prices encourage or discourage investment. Investing billions of dollars in CCUS during periods of price weakness will be challenging, and boom-and-bust weary investors may be reluctant to fund large-scale, long horizon projects even when prices are high.

At the same time, record cash flow of an estimated US$150 billion for Canadian oil and gas producers this year, and expectations that high prices will persist for some time, make allocating public funds to decarbonize the oil sector a greater political challenge amid high corporate profits.

Against this backdrop, a key goal for Canada should be to help smooth volatile investment cycles in the oil patch, and ensure consistent investment in the industry’s decarbonization. Federal and provincial governments should spread out the significant windfall revenues they accrue during high price periods to help sustain investment when the industry is struggling. And firms should commit to funding decarbonization even if oil prices falter.

The Canada Growth Fund is an important shift in the government’s approach, promising new investment structures and formalized involvement in emissions-cutting projects. While co-investing with industry in abatement projects improves financial returns, there are still significant roadblocks to large decarbonization projects. Policy uncertainty, permitting and regulatory snarls, sub-surface rights for carbon storage and liability if it leaks, and the risks associated with early stage technologies can still delay investment.

To deliberately deploy enough investment to meet rapidly approaching targets in the sector, an energy-focused stream within the Growth Fund needs to bring the right stakeholders around a single table to streamline and expedite project approvals.

Resource-rich provinces, the energy and financial industries, regulators, utilities and outside experts can partner with the Growth Fund to jointly address these roadblocks.

To reduce uncertainty, investment in oil and gas decarbonization during low price periods could see higher public contributions than during periods when industry cash flow is high, demonstrating government support when times are tougher.

Crucially, it must have some independence from the political cycle. Rather than additional budgetary allotments, public funding should be directly segregated from existing royalties and federal corporate taxes to ensure funding stability.

![]()

Canada Growth Fund’s energy stream: Who does what?

- Federal government: can ear-mark windfall corporate tax revenues from high commodity prices to major industrial decarbonization in the Growth Fund, and provide long-term carbon pricing guarantee contracts to de-risk cash flows from specific CCUS projects.

- Provincial government: should earmark a portion of the royalties for decarbonization of provincial economies, and commit to proactively reducing the free allocation of credits in provincial pricing systems to support the backstop carbon price.

- Provincial and federal regulators: would need to work with ministries industry, and local stakeholders to fast-track permitting and approvals for strategic decarbonization projects.

- Indigenous groups: which are at the forefront of both climate change and resource management, should be equity partners and have a voice in how resources are deployed.

- Private sector financial institutions: will be key partners to help industry use leverage to hit desired rates of return. Non-recourse financing supported by carbon pricing guarantees from the federal government should be explored.

- Utilities: will be key partners to help industry use leverage to hit desired rates of return. Non-recourse financing supported by carbon pricing guarantees from the federal government should be explored.

- Industry: will allocate capital as projects are approved, but will also provide expertise on how to direct investment. They must commit to making decarbonization a priority throughout the investment cycle.

Key ideas to move forward

To ensure energy and climate security, the federal government and key provinces, the private sector and Indigenous communities will need to take critical steps in the near future. Some ideas:

Avoid emissions policy that restricts or cuts near-term domestic production at a time when Western Canadian oil is addressing current market disruptions. Beyond 2030, significant efforts should be made to curtail and even wind down projects that are not aligned with Canada’s Net Zero goals. Decarbonization technologies and processes should be embedded in business models of all new projects.

Leverage the Canada Growth Fund to smooth investment cycles in the oil and gas space. Spending could incorporate larger public contributions in periods of lower oil prices and more private funding at high prices.

1. https://ihsmarkit.com/research-analysis/automotive-insights-canadian-ev-information-analysis-q4-21.html

2. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-021-03821-8

3. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/2865/a-degree-of-concern-why-global-temperatures-matter/

4. https://www.arcenergyinstitute.com/meet-the-new-boom-different-from-the-last-boom/

5. e.g., new mines built with paraffinic froth treatment, new or expansion SAGD facilities with solvents or lower SORs; derived from IHS markit estimates

6. e.g., petroleum coke boiler replacements, which industry may avoid in favour of CCUS if project economics improve

7. Costs of CCUS are highly process- and site-specific, meaning the tax credit may be sufficient for some projects, such as capture on hydrogen production facilities, and not others such as steam generation in oil sands facilities.

8. Large scale deployment of CCUS, methane-sparing processes, and offsetting residual emissions using highly credible nature based offsets or technological carbon dioxide removal

9. https://www.arcenergyinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/220307-Energy-Charts.pdf

Contributors

- Yadullah Hussain, Managing Editor, Climate and Energy, Thought Leadership Strategy

- Colin Guldimann, Economist

- Naomi Powell, Managing Editor, Economics and Thought Leadership

- Darren Chow, Senior Manager, Digital Media

- Zeba Khan, Manager of Publishing, Economics and Thought Leadership

- Aidan Smith-Edgell, Research Associate, Economics and Thought Leadership

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More