- For immigrants, a Canadian education significantly reduces skills underutilization, or the mismatch between their education levels and their jobs.

- Immigrants who study in Canada do far better in the workforce than those who don’t—and almost as well as their non-immigrant peers.

- A Canadian education promotes stronger language proficiency, faster integration into the labour market and quicker acquisition of work experience.

- This allows newcomers to overcome barriers like inadequate recognition of foreign credentials and biases in the hiring process.

- Bottom line: For newcomers, a Canadian education is a key stepping stone to labour market success. For Canada, the international student stream is a more efficient source of immigration—and a key to unlocking labour productivity.

Immigrant skills are not being fully tapped

In previous work, we identified a significant mismatch between immigrants’ education levels and the jobs they hold. This underutilization of skills is especially pronounced among those trained for industries currently plagued by labour shortages, like healthcare. According to data from the 2021 census, 30% of immigrants to Canada with a degree in medicine, dentistry, veterinary medicine, or optometry worked in unrelated fields, compared to just 4.5% of non-immigrants also educated for these fields.

The same gap exists in other sectors and tends to grow wider as the level of education attainment rises. In other words, the more academically accomplished immigrants are, the less likely they are to find jobs that match their education. This could stem from a variety of factors, including higher barriers for entry associated with higher-skilled jobs, greater lack of recognition of foreign degrees than foreign certificates or diplomas, and greater reliance on language skills (on average) in jobs that typically require a university degree.

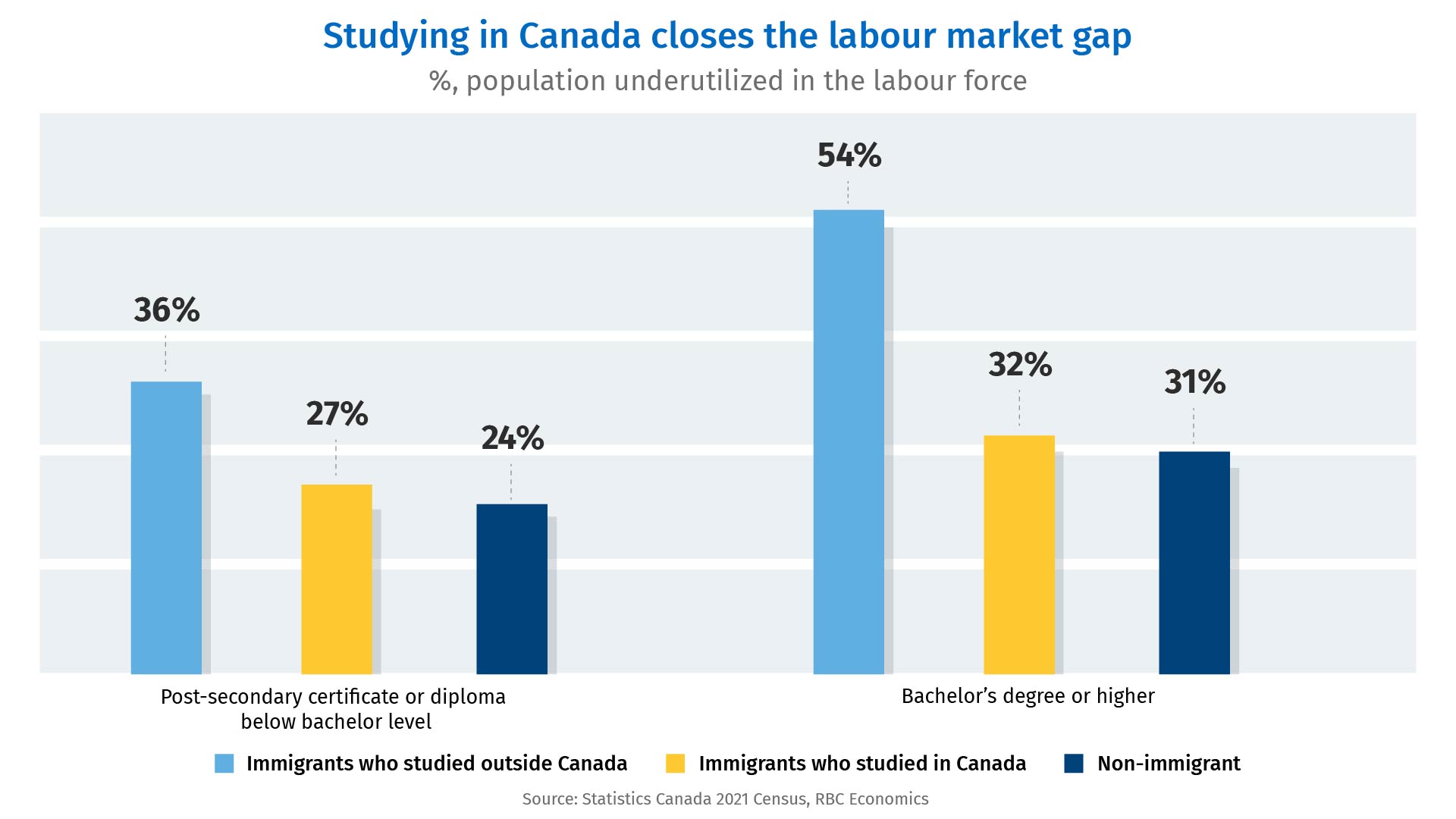

Interestingly, when immigrants receive their educations in Canada, the gap associated with labour market underutilization all but disappears.

Canadian-trained immigrants more likely to outperform in labour market

With a Canadian education, immigrants are much more likely to find jobs that match their education. Newcomers with a Canadian bachelor’s degree or higher have a 32% likelihood of being underemployed or working in occupations that require less education than their actual attainment. This compares to a 54% likelihood of underemployment for immigrants educated elsewhere and is virtually identical to the 31% underutilization rate among non-immigrant workers.

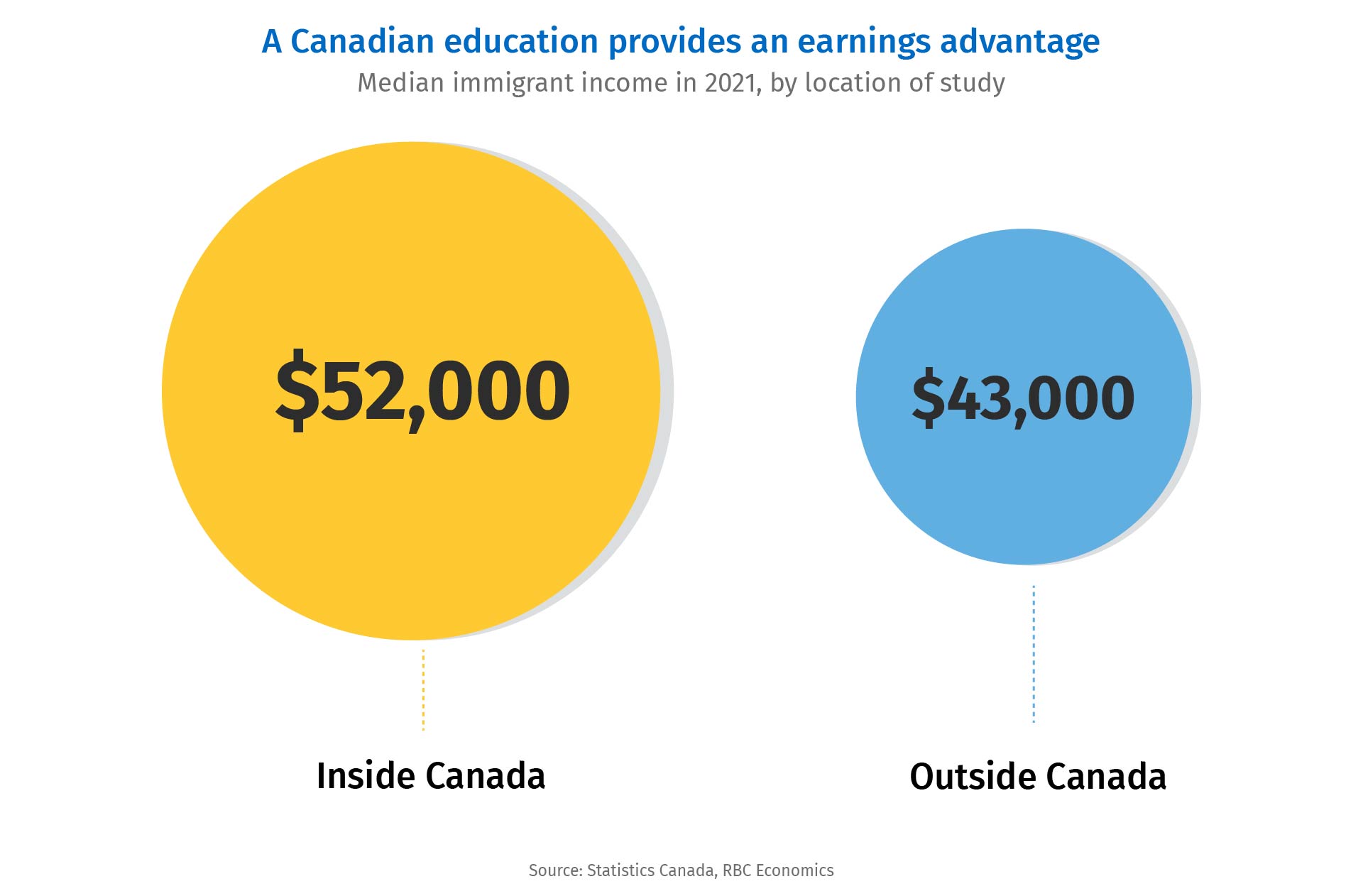

The trend extends to earnings. In 2022, Statistics Canada found that in the first two years after immigration, applicants with Canadian study experience enjoyed a considerable earnings advantage over those without it. That earnings gap was primarily a result of two things—language proficiency and pre-immigration Canadian work experience.

Indeed, a Canadian education can bridge labour market gaps in more ways than one. It offers newcomers invaluable opportunities to learn the official languages (if they do not already speak them) and enables them to begin working at a much younger age. These advantages prove incredibly valuable in helping immigrants to overcome structural biases in the labour force and to find more suitable jobs with higher incomes.

A Canadian education offers newcomers a chance to break barriers

The link between domestic education and more optimal labour market outcomes is not unique to Canada. According to the OECD, long-term employment rates among international students that remain in their host countries after graduation are at least on par with those of labour migrants or other migrant groups. And their chances of working in jobs for which they are overqualified is half that of all other groups.

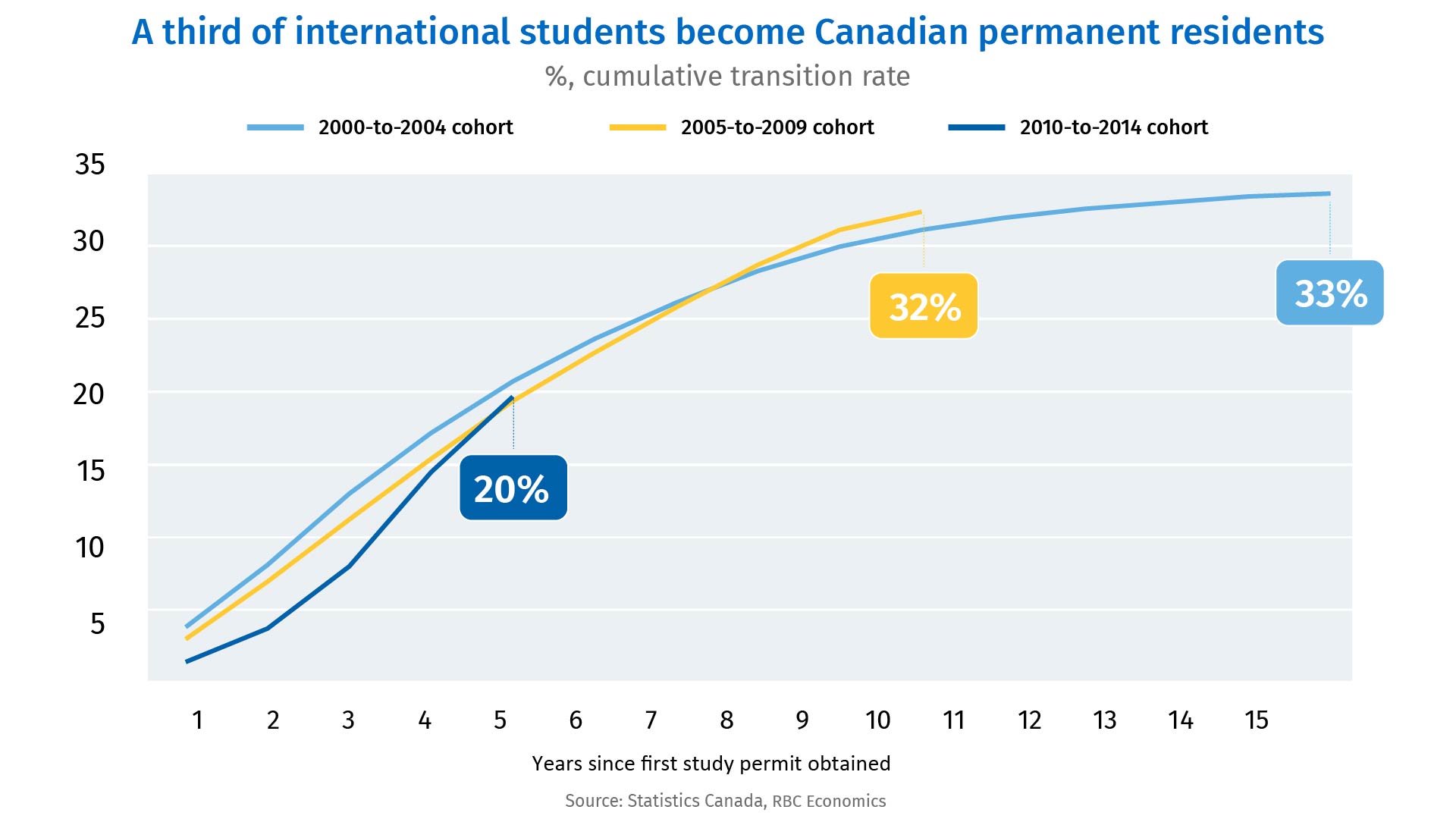

The same study found that Canada ranks especially high when it comes to incentivizing international students to remain in the country after graduation. Not all of these students will become permanent residents (PRs). Only three in ten first-time study permit holders will transition to PRs within 10 years after they’ve obtained their study permit. That rate doubles when limited to first-time study permit holders that accumulated work experience during their study.

But a Canadian education helps newcomers acquire some of the must-haves for labour market integration. And for Canada, it is a particularly efficient route for immigration. The outcome—much better utilization of immigrant skills—leads not only to better earnings potential for newcomers, but also to a better outlook for overall labour force productivity. Amid declining natural population growth, this is critical to addressing structural labour issues—which we expect to outlive a recession.

Claire Fan is an economist at RBC. She focuses on macroeconomic analysis and is responsible for projecting key indicators including GDP, employment and inflation for Canada and the US.

Proof Point is edited by Naomi Powell, Managing Editor of RBC Economics & Thought Leadership.

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More