- Canada is at an economic crossroads. In one direction, reconciliation points to a new generation of corporate thinking and government policy, leading to more Indigenous ownership, project decisions based on consent and a more sustainable approach to resource development. In the other direction, Canada could risk a return to court fights over resource rights, lost foreign investment and a diminished ability to reach Net Zero. Leading businesses and Indigenous communities have a short window of time to pick a path and forge it together.

As Canada nears the halfway mark of the 2020s, with climate challenges growing and the economy struggling, a new path of prosperity through economic reconciliation and a transformed approach to resource development can be forged. A rapidly evolving legal framework around Indigenous rights has helped create this opportunity, as have scores of communities and nations looking to shape – even control – a more equitable future.

Enhancing this new spirit of economic reconciliation between Indigenous and non-indigenous businesses will be important if Canada is to solve the challenges of climate change and slow economic growth. The imperative for action now is growing, with the country in the early stages of an energy transition and on the verge of a critical-minerals boom. A new approach to reconciliation, as laid out in this report, can not only lead to more effective resource development for Canada and sustainable economic growth for communities; it can enhance exports, boost overall productivity and engage a larger part of the Indigenous workforce in the advanced jobs and trades of a greener economy.

All sides will need to work together to increase investment in infrastructure for First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, including in the thousands of communities that both rely on and steward the natural resources on which much of Canada has been built. Canadians, whether in business, government or public life, will also need to see this as a critical chance to rebuild trust between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, and hasten all of Canada on the path to reconciliation.

At the heart of the matter is the concept of Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). FPIC sets out principles that can serve as a compass for this new path, and a means through which to enhance trust and decrease potential frictions wherever Indigenous peoples have interests and rights. FPIC is much more than a legal concept. The concept embodies a mindset of cooperation and long-term thinking that can position Canada in the eyes of global investors as a reliable and collaborative market that could offer fewer disputes and more rewards.

FPIC is a call for direct, frank and respectful conversations that move beyond “yes or no” negotiations and check-box decisions. It is also a dynamic approach that requires early and regular engagement, as well as flexibility, open-mindedness and creativity from all participants. It calls for businesses to have a respect for traditional and contemporary Indigenous knowledge and culture.

That’s what consent is. Indigenous and legal authorities agree it is not a veto. International law makes clear that FPIC is a mechanism that serves to balance all rights at stake.

Shortly after Canada committed to adopt this new rights-based approach, RBC launched a national initiative to hear from Indigenous communities about their views of engagement and consent. The initiative, led by special advisor and former National Chief Phil Fontaine, embarked on a series of “listening circles” across the country that continue to inform our approach to economic reconciliation, including a view of how Canadian business should approach development with Indigenous peoples.

These conversations will continue, and like the concept of Free, Prior and Informed Consent, will evolve as communities – and new generations – develop their own approaches to and comfort with economic reconciliation. It’s a flowing river, as one listening circle participant said, not a still pond.

While FPIC is still in its early days of implementation, (only BC and the federal government have enacted laws related to it) we heard from communities that it is not, and will not be, a fast track or free pass for project development. Early adoption shows that this consensual approach to economic development requires plenty of time and extensive engagement between groups. This approach is also about much more than deal-making or project building. It’s about the past, and helping to heal and repair pervasive and often insidious harms. And it’s about the future, and building relationships and a mutual understanding that can transcend any particular transaction. In the long run, such investments – in relationship building, knowledge sharing, cultural recognition and ultimately, power sharing – can be effective mitigants to conflict and, more positively, enduring assets for future development.

We heard from Indigenous and non-Indigenous leaders that this can be Canada’s moment, to choose the right path ahead from this crossroads. And if we apply the same concern, even urgency, as we do to other collective challenges, be it climate change or economic growth, we can go far and fast. No one expects the journey to be easy or straightforward. But the business of reconciliation promises a new economic chapter for the country, and for Indigenous peoples.

An anchor within UNDRIP, embodies the concept that Indigenous communities have the inherent right to make decisions about their lands, resources and futures.

It mandates states and businesses to engage in meaningful dialogue with Indigenous peoples, respecting their autonomy, cultural integrity and traditional knowledge, most notably in conjunction with the use of land.

The 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, established in 2007, is a legally non-binding resolution that defines the inherent rights of Indigenous Peoples around the world.

Since its inception, UNDRIP has gained international recognition as a fundamental instrument of human-rights law, with a growing number of countries including Canada endorsing its principles.

While FPIC is an international guideline, “duty to consult” and accommodate has been a legally binding obligation in Canada since 2004 that applies to the federal, provincial and territorial governments.

Duty to consult must be fulfilled by the governments, collectively called the Crown, before they take any action that may affect the rights of Indigenous peoples.

Listening Circles: Key learnings

In our Listening Circles (roundtables with community leaders across Canada), we heard:

Business should embrace FPIC as a process to help find common ground with Indigenous communities on prospective projects.

Business should embrace FPIC as a process to help find common ground with Indigenous communities on prospective projects. First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities and nations can view enhanced collaboration with the private sector, as well as government agencies, as an additional model to development, moving beyond bilateral Crown-Indigenous relations.

First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities and nations can view enhanced collaboration with the private sector, as well as government agencies, as an additional model to development, moving beyond bilateral Crown-Indigenous relations. Governments should consider Indigenous-led environmental impact assessments as sufficient for a single review process, replacing the requirement for additional reviews by outside agencies.

Governments should consider Indigenous-led environmental impact assessments as sufficient for a single review process, replacing the requirement for additional reviews by outside agencies. Ottawa should continue to clarify federal laws to ensure Indigenous consent is considered fundamental to any decision that impacts a community’s rights or way of life.

Ottawa should continue to clarify federal laws to ensure Indigenous consent is considered fundamental to any decision that impacts a community’s rights or way of life. Business should develop and share leading practices for engagement with Indigenous communities, including a new emphasis on relationship-building and knowledge-sharing. And engagement should increasingly be in the language of a community’s choice.

Business should develop and share leading practices for engagement with Indigenous communities, including a new emphasis on relationship-building and knowledge-sharing. And engagement should increasingly be in the language of a community’s choice. Indigenous communities and outside industry should view equity participation as a pivotal component of successful partnerships, and an important element of consent.

Indigenous communities and outside industry should view equity participation as a pivotal component of successful partnerships, and an important element of consent. Government and the private sector should prioritize investment in financial tools and skills in Indigenous communities to help develop local capacity to participle in, and shape, economic development.

Government and the private sector should prioritize investment in financial tools and skills in Indigenous communities to help develop local capacity to participle in, and shape, economic development.

Listening Circles

RBC has been on a journey of reconciliation, working with our Indigenous partners to listen, learn, and work towards tackling the complex challenges and emerging opportunities of our time. Together we have seen signs of progress, achieved many firsts, with recent work inspired by collaborations between Indigenous communities and the corporate sector dating back more than a quarter century. After the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples published their final report, RBC released a seminal report called The Cost of Doing Nothing which highlighted the financial implications that inaction would create, including long-term social and economic costs for Indigenous communities and Canada as a whole.

Over the past two years, RBC has joined with former Assembly of First Nations national chief Phil Fontaine to engage with Indigenous leaders and communities across Canada. Indigenous leaders spoke on the urgency and ambitions for their communities and the economic impact that it could have for all of Canada. We heard at length how interconnected issues about economic development are with community, geography and history – the need to tackle these issues together and not just in isolation – and their drive to collaborate with organizations and businesses to build a brighter future.

The magnitude and complexity of the tasks in front of us – from reconciliation to the economy to the environment – can feel formidable. However, the work we have started and the partnerships we continue to build on are key to navigating the solutions to these interlinked challenges. RBC is committed to this pathway of collaboration with our Indigenous partners – acknowledging and breaking down institutional barriers, creating new innovative approaches, driving economic empowerment and creating meaningful impact now and for generations to come. Together we can shape a stronger more sustainable future from coast to coast to coast.

The TRC was established in 2008 to confront the impacts of residential schools on Indigenous children and offer a path towards healing, and understanding between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples.

The TRC’s 94 calls to action, released in 2015, provided a framework for addressing historical injustices, promoting Indigenous rights, and building bridges to reconciliation.

This Call to Action in the TRC report was directed to the Canadian corporate sector, calling on businesses to apply UNDRIP to their principles and standards involving Indigenous Peoples, their land and resources.

No. 92 includes the appeal for businesses to commit to meaningful consultation, building respectful relationships and obtaining FPIC before proceeding with economic development projects.

A new paradigm

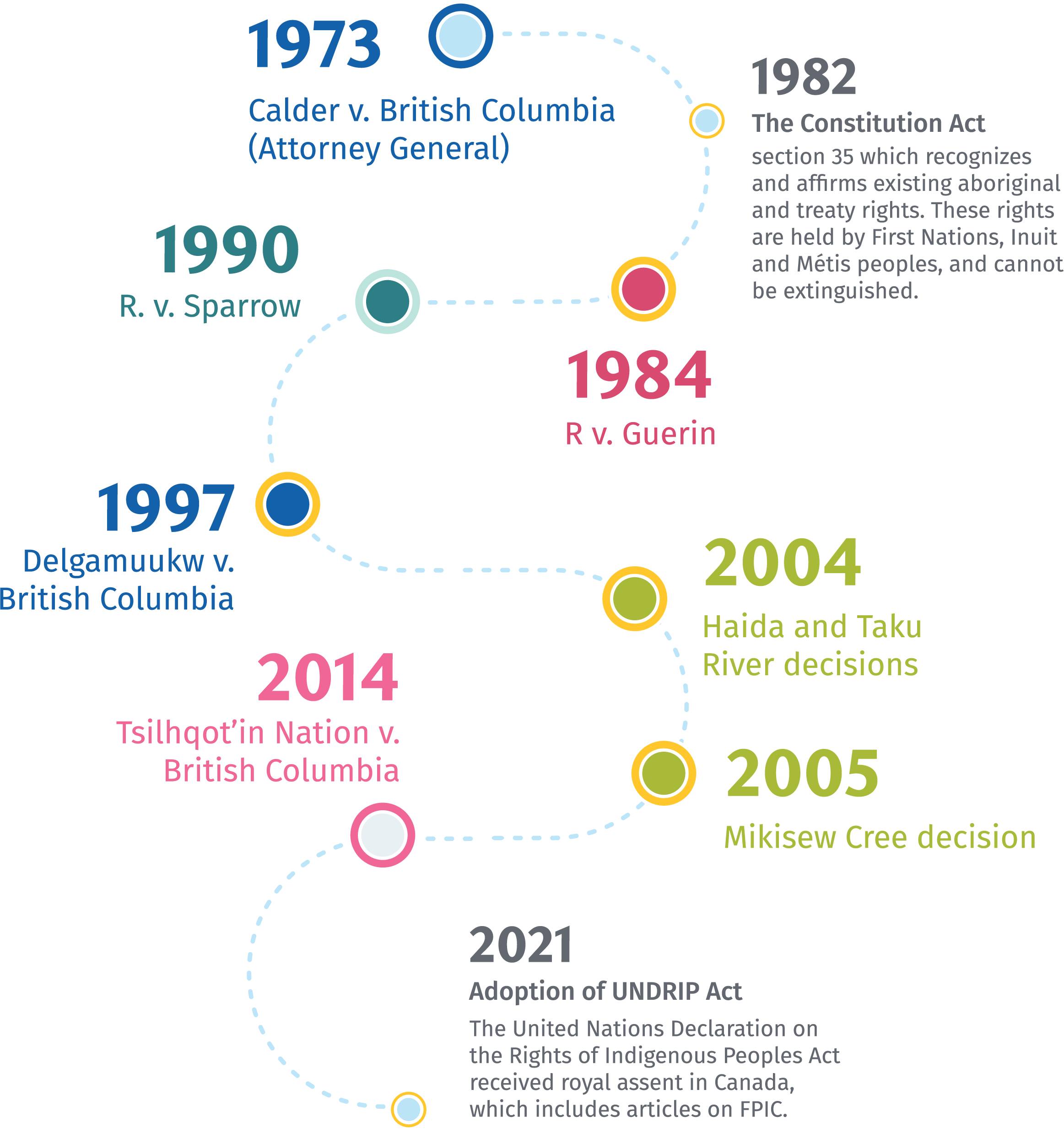

Modern Aboriginal law has evolved slowly and unevenly throughout Canada’s history. Much of Canada’s land mass is covered by historical treaties that evolved over 300 years from early diplomatic and economic alliances that shifted by the influx of settlers who created a greater demand for land. After Confederation, the numbered treaties were signed with First Nations in much of the centre of the country for settlement and access to natural resources, while regions including Atlantic Canada, eastern Ontario, and large areas of Quebec and British Columbia remained unceded. Some Indigenous groups, particularly in the North, gained autonomy much faster than others.

This left a patchwork of rules, policies and approaches that, from the point of view of some investors, created an unstable foundation for businesses to work on. Constitutional changes in the 1980s did not sufficiently clear up the matter. In the vacuum, courts have been asked to step in, and their decisions have helped delineate Indigenous rights.

In response, federal and provincial governments have been intensifying efforts to bring balance to the situation. A critical moment came in 2014 when the Supreme Court of Canada recognized Aboriginal title beyond a reserve, ruling in the Tsilhqot’in decision that Crown sovereignty needs to be balanced with Indigenous rights and self-determination. Two years later, Canada officially endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), paving the way for it to be adopted in law. Then, in June 2021, the federal government passed a law respecting the adoption in Canada of UNDRIP, which promotes Indigenous rights globally. Since then, Canada has released a UN Declaration Act Action Plan aimed at harmonizing federal laws with UNDRIP’s principles. That includes a commitment to meaningful consultation and building respectful relationships, including the desire of Indigenous communities to make business decisions based on the principle of FPIC.

Provinces and territories are making changes as well. British Columbia’s new environmental assessment act formalizes the need for consent from First Nations communities for projects on their traditional territories. B.C. is also exploring innovative amendments to its Land Act, contemplating a shared decision-making model for authorizing permits on Crown land.

First Nations Major Projects Coalition

The Act was created in 1876 as a tool to administer rights promised by the Crown, but it was applied in a way that coerced First Nations to surrender their rights and culture and severed them from the mainstream economy.

The devastating marginalization and other impacts of the Act are still felt today. New legislation is dismantling it piece by piece through the return to self-determination and self-government initiatives.

Revenues generated by Indigenous governments through taxes or resource development, or by communities through economic endeavours and development like resource extraction and tourism.

Own Source Revenues symbolize a shift towards Indigenous economic self-determination because they allow communities to fund activities such as infrastructure projects, social programs and cultural initiatives.

Contracts between Indigenous communities and project developers that outline remedies, compensation and environmental safeguards related to natural resource development on traditional lands.

While IBAs are designed to honour Indigenous rights and mitigate socio-economic impacts, they may not meet communities’ expectations if they are not comprehensive and leave too much room for interpretation.

Overcoming unique challenges

Difficulties in understanding the differences in governance systems and worldviews—not to mention inevitable discrepancies in size or financial power of business entities—have created frictions that have in places undermined collaboration. While the dynamics between Indigenous and non-Indigenous entities have improved in many ways, not all parts of the corporate sector have been quick to adapt their attitudes and policies to the new paradigm.

On a deeper level, a legacy of injustice continues to impede progress. For decades, government policies deprived Indigenous peoples of their inherent rights and decision-making powers, leading to economic underinvestment and human deprivation that continues to impact Indigenous communities. The Indian Act of 1876 marginalized First Nations communities, while other restrictive and prejudicial policies such as the residential school system and forced relocation isolated

Efforts to reverse this narrative are imperative if Canada is to advance economic reconciliation, boost economic development, strengthen productivity growth and increase climate action. Heading into the latter half of the 2020s, these objectives may well be intertwined. For instance, RBC research shows traditional Indigenous lands in Canada account for 56% of advanced critical mineral projects, 35% of the top solar sites, and 44% of the best wind sites for energy production.

In each case, Canada will struggle to meet our potential without a new approach, which in turn promises significant economic opportunities, for Indigenous communities as well as the country. Over the next decade, Canada is poised to develop 470 natural resources projects, worth an estimated $525 billion, mostly in the energy sector. The First Nations Major Projects Coalition estimates these projects could create more than $50 billion in equity opportunities for Indigenous communities.

Difficulties in understanding the differences in governance systems and worldviews—not to mention inevitable discrepancies in size or financial power of business entities—have created frictions that have in places undermined collaboration. While the dynamics between Indigenous and non-Indigenous entities hve improved in many ways, not all parts of the corporate sector have been quick to adapt their attitudes and policies to the new paradigm.

On a deeper level, a legacy of injustice continues to impede progress. For decades, government policies deprived Indigenous peoples of their inherent rights and decision-making powers, leading to economic underinvestment and human deprivation that continues to impact Indigenous communities. The Indian Act of 1876 marginalized First Nations communities, while other restrictive and prejudicial policies such as the residential school system and forced relocation isolated most Indigenous peoples from their traditional economy, as well as the mainstream economy. This multi-generational legacy has led to lingering mistrust, which grinds at the wheels of relationship-building, even in cases where there are mutually beneficial agreements around specific projects.

Efforts to reverse this narrative are imperative if Canada is to advance economic reconciliation, boost economic development, strengthen productivity growth and increase climate action. Heading into the latter half of the 2020s, these objectives may well be intertwined. For instance, RBC research shows traditional Indigenous lands in Canada account for 56% of advanced critical mineral projects, 35% of the top solar sites, and 44% of the best wind sites for energy production.

In each case, Canada will struggle to meet our potential without a new approach, which in turn promises significant economic opportunities, for Indigenous communities as well as the country. Over the next decade, Canada is poised to develop 470 natural resources projects, worth an estimated $525 billion, mostly in the energy sector. The First Nations Major Projects Coalition estimates these projects could create more than $50 billion in equity opportunities for Indigenous communities.

To fulfil that promise, here are three important steps for business to consider:

Businesses seeking to engage a community about a project on Indigenous traditional territory would be wise to take a different approach than they would elsewhere. Increasingly, First Nations, Métis and Inuitleaders expect potential partners respect their community values, governance systems, timelines and consensus-building processes, which often vary from community to community and region to region. Seeking to establish a firm understanding of values and business goals is a far different approach than traditional Impact Benefit Agreements might seek through financial transfers, jobs and procurement deals. Indigenous leaders want to be approached as long-term partners who have unique value to add, including their traditional knowledge of their lands and natural ecosystems, which in turn could de-risk projects and lead to more sustainable and profitable outcomes.

Indigenous communities also want agreements that ensure they will retain influence over the life of the project, from initial planning to remediation and reclamation. This is why they have been advocating for equity participation to become a larger component of their business partnerships. While resource royalties are valuable because they can generate long-term wealth, equity participation generates both wealth and influence. Holding an ownership position in a project—and perhaps a seat on the board of directors—also aligns Indigenous interests, including environmental, impact and investment concerns, with project partners.

At a minimum, First Nations, Métis and Inuit leaders are demanding that project proponents approach them with a respect for traditional and contemporary Indigenous knowledge and worldviews. Participants in the Listening Circles consistently stressed the importance of listening, understanding and respect.

Businesses should seek participation in proactive partnerships with Indigenous communities and government agencies. Public Private Indigenous partnerships (P3I) are an increasingly attractive model for cooperation—and a departure from the framework of Crown-Indigenous relations that dominated the Indigenous economy for decades. P3Is leverage wide economic powers and build trust. The Oneida Energy Storage Project in Southwestern Ontario provides a recent example. The energy startup NRStor worked alongside Six Nations of the Grand River Development Corporation to advocate policies and procedures to promote a battery-storage project on the territory that could help serve Ontario’s Golden Horseshoe. The result was a true P3I, with Tesla providing the battery technology, Aecon building it, and Northland Power becoming a significant backer. In 2021, the Canada Infrastructure Bank committed to invest $170 million in the $500 million project.

Promoting P3Is can also be used as a potent force to eliminate the Indigenous infrastructure gap. Efforts to close that gap should be seen not only as an effort to redress legacy injustices and promote economic reconciliation, but an integral driver to help Canada reach its commitments of climate transition (through more efficient electrical grids and housing, for instance) and increased productivity.

The private sector should accelerate investment in financial tools and people. This will allow more First Nations, Métis and Inuit groups to participate in, or take charge of, community development and resource projects—while increasing collective opportunities for Canada as a whole. The need for greater support from the private sector, and coordination with Indigenous communities, was a major theme of the listening circles. Indeed, the “free” and “informed” parts of FPIC require that Indigenous groups be able to engage in business negotiations without substantive disadvantages.

Lack of financial capacity can pose a major barrier to that kind of engagement. The availability of tools like government loan guarantee programs has begun to allow Indigenous communities to access new forms of capital – but they also need the skills and technology to leverage the opportunities and overcome challenges such as the inability to use settlement lands for collateral. In Budget 2024, the federal government detailed a new national Indigenous loan guarantee program that could add to the transformative power of business-to-business cooperation. But it will need to be accompanied by formal and informal capacity building, for communities as well as small and medium-sized Indigenous businesses.

Private-sector support for increased educational opportunities, and sector-specific training in fields such as finance, governance and engineering can promote positive economic outcomes for Indigenous peoples. A new generation of jobs, trades and professions will not only add to the income levels in many communities. It will add to the collective strength of those communities to further advance their interests and protect their values.

A new business model

Economic reconciliation can be seen as an effort to achieve balance in equity and prosperity with First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples. Free, Prior and Informed Consent can help build strong partnerships and can underpin that effort.

As Canada grapples with the implications of FPIC, Indigenous communities are not standing idly by. Many of the leaders are pursuing business deals that conform to their individual nation’s priorities and worldviews—and in many cases are striking out on their own. As we noted in our 92 to Zero report, Indigenous entrepreneurs are developing new businesses at nine times the Canadian average—while Indigenous-led development agencies are proliferating. That is transforming Indigenous relations from a one-way to a two-way street.

The private sector has a large role to play. Businesses in Canada can approach Indigenous negotiations by looking for shared goals, while offering equity rather than handouts. Those that don’t risk being outflanked by foreign firms, as well as emerging Indigenous competitors, with more collaborative approaches.

To widen the field of collective opportunities, the private sector should be seeking to create new, innovative partnership models, and look for ways to accelerate investments in financial tools and people. Businesses that follow this balanced approach, including FPIC, may find it to be far less a business risk and much more a competitive advantage. Indeed, the greatest risk of reconciliation may soon be for those who don’t embrace it.

For more, go to rbc.com/thoughtleadership.

Download the Report

Contributors:

John Stackhouse, Senior Vice President, Office of the CEO

Alanna La Rose, Senior Manager, Enterprise Strategy and Transformation

Caprice Biasoni, Graphic Design Specialist

Related Reading

This article is intended as general information only and is not to be relied upon as constituting legal, financial or other professional advice. A professional advisor should be consulted regarding your specific situation. Information presented is believed to be factual and up-to-date but we do not guarantee its accuracy and it should not be regarded as a complete analysis of the subjects discussed. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors as of the date of publication and are subject to change. No endorsement of any third parties or their advice, opinions, information, products or services is expressly given or implied by Royal Bank of Canada or any of its affiliates.

Learn More

Learn More